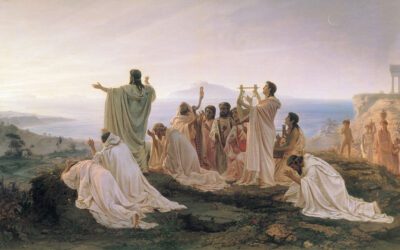

The Queen is the power behind power and the maternal influence on development. The Queen is the indirect power that we hold over authority and systems just as the magician is the indirect power we hold over peers and our immediate vicinity. She is every calculated comment that ever made you reconsider your own behavior. She is every raised eyebrow that made you behave. The Queen is long talks by the fire with a loved one about your own worst impulses. She is tempering to power, but when over identified with she becomes a manipulative puppet master behind the throne, a Bloody Mary.

The Queen uses her influence over the powerful to exercise her own power. If this concept is lost on you, then you are likely under identified with your own Queen. If this is the case, be careful, because it is the patients under identified with their own Queen who are most susceptible to be influenced by the Queen of others. If we do not understand the art of manipulation, we have no defenses against it. The Queen is, by her very nature, the least recognized archetype. The Queen is the thing behind the thing. She is the unnoticed influence on the world. The Queen is the reason that the people in charge behave better than they otherwise would.

The Queen is a mothering impulse in all of us. She sits close to our Anima or archetype of the feminine. The Queen is the part of us that wants to see the people around us grow and flourish under our watchful gaze. The Queen smiles as her children and her husband mistake her subtle suggestions for their own ideas. She is the master of the understated and implied. The Queen is consigliere, advisor, right hand man, and second in command.

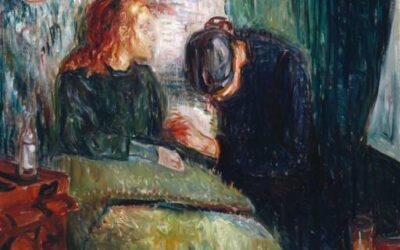

The fundamental insecurity behind the Queen is the fear that power is incompetent or malevolent. Patients with an over developed Queen usually had a competitive parent or a parent that viewed them as a peer in childhood. Like patients with an overdeveloped Magician, the child with an overdeveloped Queen may have worn this anxiety like a badge of honor in childhood. However, also like the child with an over developed Magician this damaged the child, leaving them hyper vigilant and trapped with an exhausting control instinct. Unlike patients with an over developed Magician, patients with an overdeveloped Queen felt responsible for running a household by proxy and controlling an irascible or inconsistent parent. They did not seek to be understood or get attention from a caregiver like children with an overidentified Magician.

Patients that present to therapy reporting that they are the “therapist for all their friends” or that “everyone asks them for advice” have a healthy identification with their Queen. The over identified Queen is not content to advise power, but wants to control it from the shadows as a puppeteer. Overidentification with the Queen leads patients to become obsessed with subtly influencing other people as extensions of themselves and power. Manipulative patients, who begin to hold their altruism over the heads of those they are helping are on the road to over identification with the Queen. Therapists should be aware of the functioning of this archetype, as it is the role of the therapist to play The Queen in the patient’s life during the process of therapy.

The over identified Queen as a mother does not want children to develop as individuals outside of the family or have a personal identity. Children are to remain a part of her and only exist as her accessory and a reflection of her purposes and her values. The over identified Queen wants to know all her children’s secrets, and to get to tell them exactly who they should become. Because patients who had a mother over identified with her own Queen never had the chance to listen to their own inner voice during development they will present to therapy with a bothersome inner critic that reflects the internalized critical voice of the parent. This overwhelming voice of inner criticism is the implanted voice of the parent that did not want their Child to exist outside their own sphere.

Bibliography:

Jung, C.G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R.F.C. Hull, Routledge, 1991.

Moore, Robert, and Douglas Gillette. King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine. HarperOne, 1991.

Pinkola Estés, Clarissa. Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. Ballantine Books, 1992.

Hollis, James. The Eden Project: In Search of the Magical Other. Inner City Books, 1998.

Bly, Robert. Iron John: A Book About Men. Vintage, 1992.

Further Reading:

Edinger, Edward F. Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Shambhala, 1992.

Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Princeton University Press, 1972.

Downing, Christine. The Goddess: Mythological Images of the Feminine. Continuum, 1999.

Bolen, Jean Shinoda. Goddesses in Everywoman: Powerful Archetypes in Women’s Lives. HarperOne, 2014.

Zweig, Connie, and Jeremiah Abrams, editors. Meeting the Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature. Tarcher/Putnam, 1991.

Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row, 1975.

Johnson, Robert A. We: Understanding the Psychology of Romantic Love. HarperOne, 1983.

Groesbeck, C. Jess. “The Spirit in the Healing Process.” Harvest: Journal for Jungian Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, 1984, pp. 113-126.

Sharp, Daryl. Jung Lexicon: A Primer of Terms & Concepts. Inner City Books, 1991.

0 Comments