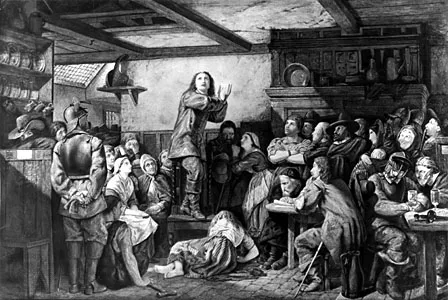

Who was George Fox?

George Fox (1624-1691), the founder of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), developed a form of Christian spirituality that continues to offer valuable insights for contemporary psychology and spiritual practices. This article explores Fox’s key teachings and their relevance to modern well-being and personal growth.

Key Concepts in Fox’s Teachings

1. The Inner Light

- Central to Fox’s philosophy

- Belief in direct, unmediated experience of God within every individual

- Challenges traditional notions of external spiritual authority

2. Simplicity and Plainness

- Rejection of elaborate rituals and excess

- Emphasis on inward experience over outward forms

- Relevance to mindfulness and minimalism in modern life

3. Equality and Social Justice

- Belief in the fundamental equality of all people

- Commitment to non-violence and pacifism

- Advocacy for marginalized groups

4. Silent Worship and Discernment

- Practice of “expectant waiting” in group settings

- Emphasis on communal discernment

- Parallels with contemporary meditation practices

5. Testimonies and Witness

- Core values: simplicity, peace, integrity, community, and equality

- Living out spiritual beliefs in daily life and social engagement

Implications for Contemporary Psychology and Spirituality

- Introspection and Mindfulness: Fox’s emphasis on the Inner Light aligns with modern interest in mindfulness and meditation.

- Simplicity and Well-being: Quaker commitment to simplicity offers a counterpoint to materialism, promoting contentment and sustainability.

- Engaged Spirituality: Integration of spiritual values with social action provides a model for purpose-driven living.

- Supportive Communities: Quaker practices of silent worship and communal discernment offer insights for building meaningful spiritual communities.

- Holistic Approach: Quaker insights can contribute to a more integrated understanding of well-being, combining spiritual, psychological, and social dimensions.

George Fox and the Quaker tradition provide a rich source of inspiration for those seeking to cultivate deeper meaning, purpose, and connection in their lives. By integrating Quaker insights with contemporary psychological science, we can develop more holistic approaches to well-being that honor the full complexity of the human spirit.

Bibliography:

- Fox, G. (1694). Journal of George Fox. (Published posthumously)

- Fox, G. (1659). The Great Mistery of the Great Whore Unfolded.

- Fox, G. (1660). A Declaration from the Harmless and Innocent People of God, Called Quakers.

- Fox, G. (1661). The Journal of George Fox (edited by Norman Penney, 1924).

Further Reading:

- Brinton, H. (1952). Friends for 300 Years. Harper & Brothers.

- Dandelion, P. (2007). An Introduction to Quakerism. Cambridge University Press.

- Gwyn, D. (1995). The Covenant Crucified: Quakers and the Rise of Capitalism. Pendle Hill Publications.

- Hamm, T.D. (2003). The Quakers in America. Columbia University Press.

- Ingle, H.L. (1994). First Among Friends: George Fox and the Creation of Quakerism. Oxford University Press.

- Jones, R.M. (1921). The Later Periods of Quakerism. Macmillan and Co.

- Moore, R. (2000). The Light in Their Consciences: Early Quakers in Britain, 1646-1666. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Nickalls, J.L. (ed.) (1952). The Journal of George Fox. Cambridge University Press.

- Punshon, J. (1984). Portrait in Grey: A Short History of the Quakers. Quaker Home Service.

- Vann, R.T. (1969). The Social Development of English Quakerism, 1655-1755. Harvard University Press.

- Barbour, H. & Roberts, A.O. (2004). Early Quaker Writings 1650-1700. Wallingford, PA: Pendle Hill Publications.

- Birkel, M.L. (2004). Silence and Witness: The Quaker Tradition. Orbis Books.

- Dandelion, P. (2005). The Liturgies of Quakerism. Ashgate Publishing.

- Palmer, P.J. (1993). To Know as We Are Known: Education as a Spiritual Journey. HarperOne.

- Steere, D.V. (1967). On Listening to Another. Harper & Row.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

0 Comments