Simulacra and Simulation

“We are in a logic of simulation, which no longer has anything to do with a logic of facts and an order of reason. Simulation is characterized by a precession of the model, of all the models based on the merest fact – the models come first, their circulation, orbital like that of the bomb, constitutes the genuine magnetic field of the event. The facts no longer have a specific trajectory, they are born at the intersection of models, a single fact can be engendered by all the models at once.” (Simulacra and Simulation, 1981)

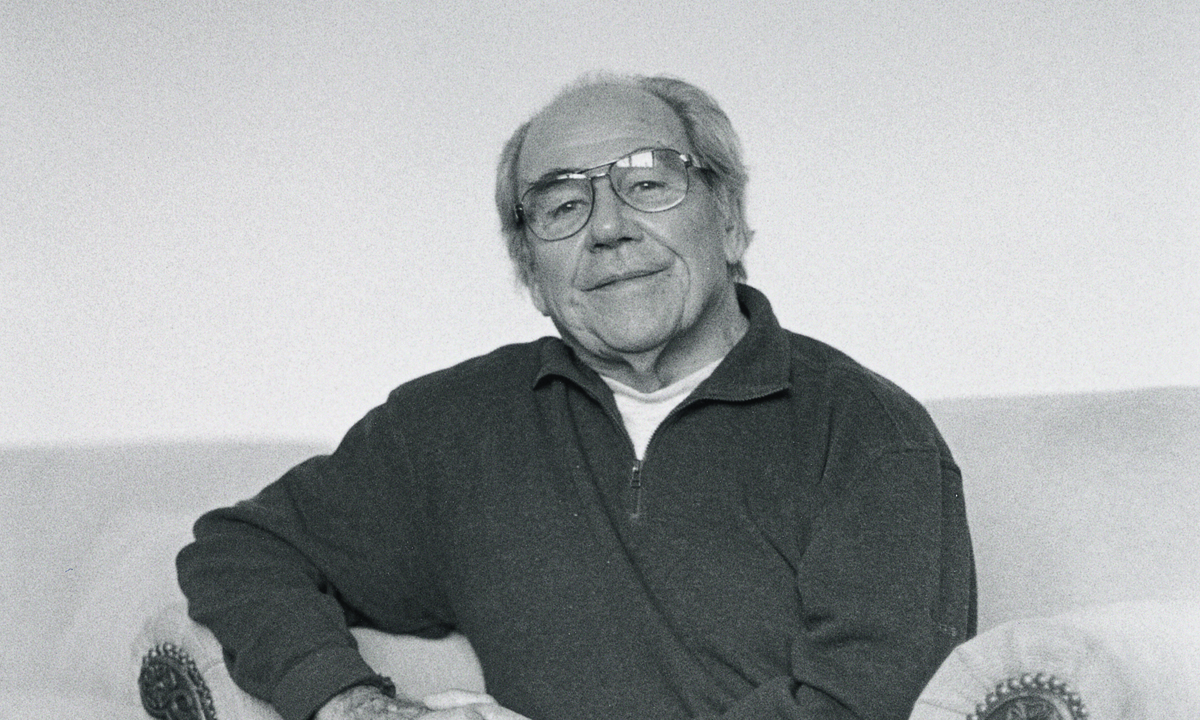

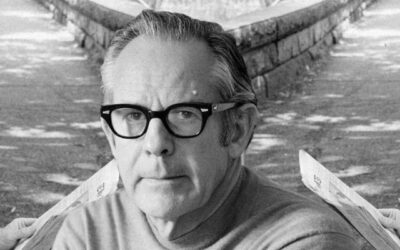

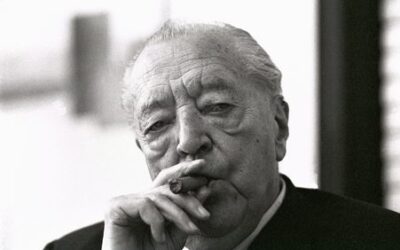

I. Who was Jean Baudrillard

Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) was a French sociologist, philosopher, cultural theorist, and provocateur who made significant contributions to the understanding of media, technology, and postmodern culture in the late 20th century. Baudrillard’s work, which spans across multiple disciplines, offers a radical critique of contemporary society and its relationship with reality, simulation, and the image. His ideas about hyperreality, simulacra, and the implosion of meaning continue to influence debates in fields such as media studies, sociology, philosophy, and psychoanalysis.

This paper explores the life and ideas of Jean Baudrillard, situating his thought within the historical and intellectual context of postwar France and examining its enduring relevance for understanding the challenges of the digital age. By engaging with Baudrillard’s key concepts, such as simulation, hyperreality, and the orders of simulacra, and by considering their implications for fields such as psychology, anthropology, and media studies, this paper seeks to illuminate the significance of Baudrillard’s work for navigating the blurred boundaries between reality and illusion in contemporary culture.

II. Biography of Jean Baudrillard

“All of Western faith and good faith was engaged in this wager on representation: that a sign could refer to the depth of meaning, that a sign could exchange for meaning and that something could guarantee this exchange – God, of course.” (Simulacra and Simulation, 1981)

Jean Baudrillard was born in Reims, France in 1929 to a peasant family. He was the first in his family to attend university, studying German at the Sorbonne in Paris. After completing his degree, Baudrillard worked as a high school German teacher and translator. In the 1960s, he began his academic career, teaching sociology at the University of Paris X Nanterre.

Baudrillard’s early work was influenced by Marxism and structuralism, as well as by the events of May 1968 in France, which saw massive student and worker protests against the government and traditional institutions. In his first major work, “The System of Objects” (1968), Baudrillard explored the ways in which objects and commodities shape social relations and identity in consumer society.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Baudrillard developed his distinctive theoretical approach, moving away from traditional Marxist and sociological frameworks towards a more radical critique of media, technology, and postmodern culture. Works such as “Simulacra and Simulation” (1981) and “America” (1986) established Baudrillard as a major intellectual figure, known for his provocative and often controversial ideas about the nature of reality and meaning in contemporary society.

In his later work, Baudrillard continued to explore themes of simulation, technology, and the media, while also engaging with topics such as globalization, terrorism, and the Gulf War. He remained a prolific writer and commentator until his death in 2007.

III. Overview of Key Ideas

At the core of Baudrillard’s philosophy is a radical critique of the relationship between reality, representation, and meaning in contemporary society. For Baudrillard, the postmodern age is characterized by a collapse of the distinction between the real and the simulated, leading to a condition he terms “hyperreality.” In this context, signs and images no longer refer to an external reality but instead constitute a self-referential system of simulation.

One of Baudrillard’s key concepts is the idea of simulacra, or copies without an original. In his book “Simulacra and Simulation,” Baudrillard argues that contemporary culture is characterized by the proliferation of simulacra, which have replaced the real as the basis for meaning and experience. He identifies three orders of simulacra: the counterfeit, which imitates the real; production, which mass-produces the real; and simulation, which precedes and determines the real.

For Baudrillard, the rise of simulation and hyperreality has profound consequences for our understanding of truth, meaning, and social relations. In a world where images and signs have lost their referents, categories such as truth and falsity, reality and illusion, subject and object become increasingly unstable and fluid. This leads to what Baudrillard terms the “implosion of meaning,” as the boundaries between different spheres of social life – politics, economics, culture – collapse into a seamless network of simulation.

Baudrillard’s critique of media and technology is central to his analysis of postmodern culture. He argues that the media do not simply represent reality but actively construct and shape it through the production and circulation of signs and images. In this sense, the media are not neutral channels of communication but rather powerful agents of simulation that blur the boundaries between the real and the imaginary.

Baudrillard’s work also engages with questions of power, resistance, and social change in the context of postmodern capitalism. He argues that traditional forms of political critique and resistance are no longer effective in a world where power operates through the manipulation of signs and the seduction of the masses. Instead, Baudrillard advocates for a form of “fatal strategy” that embraces the simulacra and the hyperreal as a means of subverting the system from within.

Key concepts in Baudrillard’s Philosophy:

Hyperreality:

The condition where the distinction between the real and the simulated collapses, and reality is replaced by simulacra.

Simulacra:

Copies without an original, which constitute the basis for meaning and experience in postmodern culture. Baudrillard identifies three orders of simulacra:

- The counterfeit, which imitates the real

- Production, which mass-produces the real

- Simulation, which precedes and determines the real

Implosion of Meaning:

The collapse of boundaries between different spheres of social life (politics, economics, culture) into a seamless network of simulation, resulting in the destabilization of meaning.

Media and Technology:

Not mere representations of reality, but active constructors and shapers of it through the production and circulation of signs and images.

Fatal Strategy:

Embracing the simulacra and the hyperreal as a means of subverting the system of postmodern capitalism from within, as traditional forms of critique become ineffective.

IV. Implications for Psychology, Anthropology, and Media Studies

Baudrillard’s ideas have significant implications across various disciplines, including psychology, anthropology, and media studies. His analysis of hyperreality, simulacra, and the implosion of meaning offers a provocative framework for understanding the psychological, social, and cultural effects of media and technology in the postmodern age.

A. Relevance to Psychology and Trauma Treatment

From a psychological perspective, Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality raises important questions about the nature of reality, identity, and mental health in a media-saturated world. His suggestion that the boundaries between the real and the simulated have collapsed resonates with the experiences of individuals who struggle to differentiate between reality and fantasy, such as those with psychotic disorders or dissociative conditions.

In the context of trauma treatment, Baudrillard’s ideas about simulation and the implosion of meaning may provide insight into the ways in which traumatic experiences can disrupt an individual’s sense of reality and identity. The concept of simulacra, in particular, may be relevant to understanding the role of flashbacks, intrusive memories, and other trauma-related phenomena that blur the boundaries between past and present, real and imagined.

Baudrillard’s work also intersects with the ideas of depth psychologists such as Carl Jung and existential therapists such as Rollo May. Like Baudrillard, these thinkers emphasized the importance of symbolism, meaning, and the search for authenticity in the face of an increasingly alienating and dehumanizing world. They recognized the power of images and archetypes to shape human experience and sought to help individuals navigate the complexities of modern life.

However, Baudrillard’s postmodern approach differs from traditional psychological frameworks in its radical skepticism towards notions of truth, reality, and the self. For Baudrillard, the very idea of an authentic self or a stable reality is called into question by the proliferation of simulacra and the implosion of meaning. This poses challenges for psychologists and therapists who seek to help individuals achieve a coherent sense of self and a meaningful engagement with the world.

B. Relevance to Anthropology and the Study of Culture

Baudrillard’s work also has significant implications for anthropology and the study of culture. His analysis of the role of objects, commodities, and signs in shaping social relations and identity offers a powerful framework for understanding the ways in which material culture and symbolic systems structure human experience.

Baudrillard’s concept of simulacra, in particular, may be relevant to understanding the ways in which cultural representations and practices can take on a life of their own, detached from their original referents. This is evident, for example, in the proliferation of tourist sites and cultural performances that simulate “authentic” experiences for consumption by global audiences.

Baudrillard’s critique of consumer society and the media also resonates with anthropological debates about the impact of globalization and technological change on traditional cultures and ways of life. His work challenges anthropologists to grapple with the ways in which the boundaries between the local and the global, the real and the simulated, are increasingly blurred in the postmodern world.

At the same time, Baudrillard’s radical skepticism towards notions of truth, meaning, and social reality poses challenges for anthropologists who seek to represent and interpret cultural phenomena. His work calls into question the very possibility of ethnographic knowledge and the authority of the anthropologist as a neutral observer of social life

“Deep down, no one really believes they have a right to live. But this death sentence generally stays tucked away, hidden beneath the difficulty of living. If that difficulty is removed from time to time, death is suddenly there, unintelligibly.” (America, 1986)

C. Relevance to Media Studies and the Analysis of Technology

Finally, Baudrillard’s work is deeply relevant to media studies and the analysis of technology in contemporary society. His concepts of simulation, hyperreality, and the implosion of meaning provide a powerful framework for understanding the ways in which media and technology shape human perception, communication, and social relations.

Baudrillard’s critique of the media as agents of simulation resonates with debates in media studies about the role of news, advertising, and social media in constructing and manipulating reality. His work challenges media scholars to grapple with the ways in which the boundaries between fact and fiction, information and entertainment, are increasingly blurred in the digital age.

Baudrillard’s analysis of the implosion of meaning also has implications for understanding the fragmentation and polarization of public discourse in the era of social media and fake news. His work suggests that the proliferation of simulacra and the collapse of stable referents may contribute to the erosion of shared reality and the rise of competing truth claims.

At the same time, Baudrillard’s work points to the subversive potential of media and technology to challenge dominant power structures and create new forms of resistance and social change. His concept of fatal strategy, in particular, suggests that embracing the simulacra and the hyperreal may be a way of subverting the system from within, by exposing its contradictions and absurdities.

“The necessity of leaving history behind, of building a society totally free of it, is the catastrophe of our modern societies. For without a vision of the past, the present is unintelligible and the future unthinkable.” (The Illusion of the End, 1992)

V. Baudrillard’s Relevance in the Digital Age

Baudrillard’s work remains highly relevant in the digital age, as the proliferation of new media technologies and the rise of virtual worlds and artificial intelligence continue to blur the boundaries between the real and the simulated. His ideas about hyperreality, simulacra, and the implosion of meaning provide a powerful framework for understanding the psychological, social, and political implications of these developments.

In the realm of social media, for example, Baudrillard’s concept of simulacra is evident in the proliferation of fake news, deepfakes, and other forms of manipulated content that blur the lines between truth and fiction. The rise of influencer culture and the commodification of personal identity on platforms like Instagram and TikTok also resonate with Baudrillard’s critique of consumer society and the role of images in shaping social relations.

In the field of virtual reality and gaming, Baudrillard’s ideas about hyperreality and the implosion of meaning are particularly relevant. The immersive nature of VR experiences and the increasing sophistication of game worlds raise questions about the nature of reality and identity in the digital age. Baudrillard’s work suggests that these technologies may not simply represent reality but actively shape and construct it, blurring the boundaries between the virtual and the real.

The rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning also intersects with Baudrillard’s ideas about simulation and the precession of simulacra. As AI systems become increasingly sophisticated in their ability to generate realistic images, sounds, and texts, they raise questions about the nature of creativity, originality, and authorship. Baudrillard’s work challenges us to grapple with the implications of a world in which machines can simulate human intelligence and even emotions.

At the same time, Baudrillard’s work points to the subversive potential of digital technologies to challenge dominant power structures and create new forms of resistance and social change. The rise of hashtag activism, meme culture, and other forms of digital protest resonate with Baudrillard’s concept of fatal strategy, suggesting that embracing the simulacra and the hyperreal may be a way of subverting the system from within.

“It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real.” (Simulacra and Simulation, 1981)

VI. Legacy

Jean Baudrillard’s work offers a provocative and challenging perspective on the nature of reality, meaning, and social relations in the postmodern age. His concepts of hyperreality, simulacra, and the implosion of meaning provide a powerful framework for understanding the psychological, social, and political implications of media and technology in contemporary society.

While Baudrillard’s radical skepticism towards notions of truth, reality, and the self poses challenges for traditional academic disciplines, his work remains highly relevant for navigating the complexities of the digital age. As we grapple with the implications of new media technologies, artificial intelligence, and virtual worlds, Baudrillard’s ideas offer valuable insights into the blurring boundaries between the real and the simulated.

At the same time, Baudrillard’s work points to the subversive potential of media and technology to challenge dominant power structures and create new forms of resistance and social change. As we seek to navigate the challenges and opportunities of the postmodern world, Baudrillard’s legacy reminds us of the importance of critical thinking, creative experimentation, and the willingness to embrace the unknown.

Timeline of Baudrillard’s Life & Key Works

- 1929 – Born in Reims, France

- 1956 – Begins teaching German at a French high school

- 1966 – Publishes his first book, “The System of Objects”

- 1968 – Publishes “The Consumer Society”

- 1972 – Publishes “For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign”

- 1976 – Publishes “Symbolic Exchange and Death”

- 1981 – Publishes “Simulacra and Simulation”

- 1983 – Publishes “Fatal Strategies”

- 1986 – Publishes “America”

- 1987 – Publishes “The Ecstasy of Communication”

- 1990 – Publishes “Seduction”

- 1991 – Publishes “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place”

- 1995 – Publishes “The Perfect Crime”

- 2007 – Dies in Paris, France

Baudrillard’s Influence on Other Thinkers

Baudrillard’s provocative ideas have influenced a wide range of thinkers across various disciplines, from philosophy and sociology to media studies and art theory. Some notable figures who have engaged with Baudrillard’s work include:

Slavoj Žižek, a Slovenian philosopher and cultural critic, has drawn on Baudrillard’s concepts of simulation and hyperreality in his analysis of ideology, popular culture, and political economy. Žižek’s work often engages with Baudrillard’s ideas, both critically and affirmatively, as part of a broader dialogue with postmodern and psychoanalytic theory.

Paul Virilio, a French cultural theorist and urbanist, shares Baudrillard’s concern with the impact of technology and media on contemporary society. Virilio’s concepts of dromology (the science of speed) and the integral accident resonate with Baudrillard’s analysis of simulation and the implosion of meaning in the postmodern age.

Arthur Kroker, a Canadian political theorist and cultural critic, has been strongly influenced by Baudrillard’s work on technology, media, and postmodern culture. Kroker’s books, such as “The Possessed Individual” and “Spasm,” draw on Baudrillard’s concepts of simulation, seduction, and fatal strategy to analyze the digital age’s challenges.

Mark Poster, an American media theorist and historian, has engaged extensively with Baudrillard’s work on media, technology, and postmodernism. Poster’s books, such as “The Mode of Information” and “The Second Media Age,” build on Baudrillard’s insights to explore the social and political implications of new media technologies.

Douglas Kellner, an American philosopher and cultural critic, has written extensively on Baudrillard’s work, offering both critical and sympathetic readings of his ideas. Kellner’s book “Jean Baudrillard: From Marxism to Postmodernism and Beyond” provides a comprehensive overview of Baudrillard’s intellectual trajectory and his place in contemporary social theory.

These are just a few examples of the many thinkers who have been influenced by Baudrillard’s ideas. His work continues to generate debate and inspire new perspectives across a range of disciplines, testifying to the enduring relevance of his provocative and challenging insights.

Criticisms and Controversies

While Baudrillard’s work has been highly influential, it has also been the subject of significant criticism and controversy. Some of the main criticisms leveled against Baudrillard include:

Nihilism and Fatalism:

Some critics argue that Baudrillard’s radical skepticism towards notions of truth, meaning, and reality leads to a kind of nihilism or fatalism, in which any possibility of positive social change or political resistance is foreclosed. They see his work as a form of postmodern relativism that undermines the foundations of critical theory and progressive politics.

Lack of Empirical Grounding:

Another common criticism of Baudrillard’s work is that it lacks empirical grounding or evidence to support his sweeping claims about the nature of contemporary society. Critics argue that his concepts of simulation, hyperreality, and the implosion of meaning are more rhetorical than substantive, and that they do not adequately engage with the complexities of actual social, economic, and political realities.

Neglect of Power and Inequality:

Some critics argue that Baudrillard’s focus on the play of signs and the seduction of simulacra neglects the material realities of power, inequality, and exploitation in contemporary society. They see his work as a form of postmodern relativism that fails to account for the structural and systemic dimensions of domination and resistance.

Inconsistency and Contradiction:

Finally, some critics point to inconsistencies and contradictions in Baudrillard’s work, arguing that his ideas shift and change over time without always being fully developed or reconciled. They see his work as more of a series of provocative gestures than a coherent philosophical system.

Despite these criticisms, Baudrillard’s work continues to be widely read and debated, and his ideas remain influential across a range of disciplines. While his provocative style and radical skepticism may not appeal to everyone, his insights into the nature of media, technology, and postmodern culture continue to generate new perspectives and lines of inquiry.

Jean Baudrillard’s philosophy offers a radical and provocative perspective on the nature of reality, meaning, and social relations in the postmodern age. His concepts of hyperreality, simulacra, and the implosion of meaning provide a powerful framework for understanding the psychological, social, and political implications of media and technology in contemporary society.

While Baudrillard’s work has been the subject of significant criticism and controversy, his insights into the blurring boundaries between the real and the simulated remain highly relevant for navigating the challenges of the digital age. As we grapple with the implications of new media technologies, artificial intelligence, and virtual worlds, Baudrillard’s legacy reminds us of the importance of critical thinking, creative experimentation, and the willingness to question the very foundations of our social reality.

At the same time, Baudrillard’s work points to the subversive potential of embracing the simulacra and the hyperreal as a means of challenging dominant power structures and creating new forms of resistance and social change. As we seek to navigate the complexities of the postmodern world, Baudrillard’s ideas offer valuable tools for imagining alternative futures and pushing the boundaries of what is possible.

Ultimately, engaging with Baudrillard’s philosophy requires a willingness to embrace uncertainty, ambiguity, and paradox. It means letting go of fixed notions of truth, meaning, and identity, and opening oneself up to the play of signs and the seduction of simulacra. While this may be a disorienting and even unsettling prospect, it is also an invitation to explore new modes of thinking, feeling, and being in the world. As Baudrillard himself put it, “The only way to grasp the real is to confront the impossible.”

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

The Left and Right Hand Path in Cultural Psychology

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

- Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

- Baudrillard, Jean. America. Translated by Chris Turner. London: Verso, 1988.

- Baudrillard, Jean. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. Translated by Chris Turner. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1998.

- Baudrillard, Jean. The System of Objects. Translated by James Benedict. New York: Verso, 1996.

- Baudrillard, Jean. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. Translated by Charles Levin. St. Louis: Telos Press, 1981.

- Baudrillard, Jean. The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Translated by Paul Patton. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Secondary Sources:

- Kellner, Douglas. Jean Baudrillard: From Marxism to Postmodernism and Beyond. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989.

- Poster, Mark. Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988.

- Gane, Mike. Jean Baudrillard: In Radical Uncertainty. London: Pluto Press, 2000.

- Pawlett, William. Jean Baudrillard: Against Banality. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Smith, Richard G., and David B. Clarke, eds. Jean Baudrillard: Fatal Theories. London: Routledge, 2009.

- Hegarty, Paul. Jean Baudrillard: Live Theory. London: Continuum, 2004.

- Butler, Rex. Jean Baudrillard: The Defence of the Real. London: Sage Publications, 1999.

- Merrin, William. Baudrillard and the Media: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005.

0 Comments