Who was Jean Piaget?

1. Overview

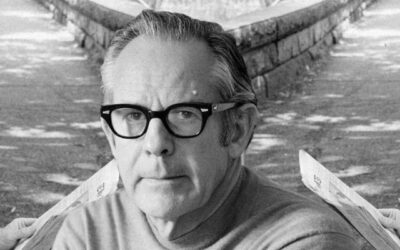

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was a Swiss psychologist and epistemologist who revolutionized our understanding of cognitive development in children. His groundbreaking work laid the foundation for the field of genetic epistemology and profoundly influenced educational theory and practice worldwide. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, with its emphasis on how children actively construct their understanding of the world, remains one of the most influential frameworks in developmental psychology and education.

This paper provides an in-depth exploration of Piaget’s key theories, their implications, and their enduring relevance in psychology, education, and beyond.

2. Main Ideas and Key Points

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development posits that children progress through four distinct stages of intellectual growth: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

Central to Piaget’s work is the concept of schemas – mental representations or categories of knowledge that children use to organize and interpret their experiences.

Piaget proposed that cognitive development occurs through the processes of assimilation (fitting new information into existing schemas) and accommodation (modifying schemas to fit new information).

The principle of equilibration – the drive to achieve a balance between assimilation and accommodation – is seen as the fundamental mechanism of cognitive growth.

Piaget emphasized the role of active exploration and hands-on experience in children’s learning, challenging the prevailing behaviorist views of his time.

His work highlighted the qualitative differences in thinking between children and adults, arguing that children are not simply “little adults” but have unique ways of understanding the world.

. Piaget’s research methods, including clinical interviews and careful observation of children’s behavior, pioneered new approaches to studying cognitive development.

. His theory has significant implications for education, suggesting that learning should be tailored to a child’s developmental level and emphasize active discovery rather than passive reception of knowledge.

Piaget’s work on moral development explored how children’s understanding of rules, fairness, and justice evolves as they mature.

His investigations into children’s conceptions of physical phenomena, such as conservation and object permanence, revealed fundamental shifts in logical thinking across development.

Piaget’s theory has been both highly influential and subject to critique, leading to ongoing debates and refinements in the field of developmental psychology.

The Piagetian perspective continues to inform research and practice in areas ranging from education and cognitive science to artificial intelligence and philosophy of mind.

3. The Stages of Cognitive Development

3.1. The Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to 2 years)

Piaget proposed that infants and toddlers understand the world primarily through their senses and motor actions. During this stage, children develop object permanence – the understanding that objects continue to exist even when out of sight. They also begin to engage in goal-directed behavior and develop the ability to mentally represent objects and actions (the beginnings of symbolic thought).

Key developments:

- Reflexes evolve into more intentional actions

- Circular reactions emerge (repeating actions to reproduce interesting effects)

- Object permanence develops

- Deferred imitation appears (imitating actions seen earlier)

- Rudimentary problem-solving emerges

3.2. The Preoperational Stage (2 to 7 years)

In this stage, children begin to use symbols (like words and images) to represent objects and ideas. However, their thinking is still characterized by egocentrism (difficulty seeing things from other perspectives) and a lack of logical operations.

Key features:

- Symbolic function develops (use of language, symbolic play)

- Egocentrism predominates

- Animism (attributing life to inanimate objects)

- Inability to conserve (understand that quantity remains the same despite changes in appearance)

- Lack of reversibility in thinking

- Transductive reasoning (drawing connections between unrelated events)

3.3. The Concrete Operational Stage (7 to 11 years)

Children at this stage can perform logical operations on concrete objects and situations. They develop the ability to conserve and classify, and their thinking becomes more flexible and less egocentric.

Key developments:

- Conservation (of number, mass, volume)

- Classification and seriation skills

- Reversibility in thinking

- Decentration (ability to focus on multiple aspects of a problem)

- Less egocentric perspective-taking

3.4. The Formal Operational Stage (11 years and older)

In this final stage, adolescents and adults can think abstractly and hypothetically. They can engage in deductive reasoning, consider multiple variables, and think about thinking itself (metacognition).

Key features:

- Abstract and hypothetical thinking

- Propositional logic

- Scientific reasoning

- Idealism and possibility-oriented thinking

- Increased metacognition

4. The Mechanisms of Cognitive Development

4.1. Schemas

Piaget proposed that our knowledge is organized into mental structures called schemas. These are dynamic, evolving frameworks that we use to interpret and respond to the world. As we encounter new experiences, our schemas are continually refined and elaborated.

4.2. Assimilation and Accommodation

Cognitive growth occurs through the twin processes of assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation involves fitting new information into existing schemas, while accommodation requires modifying schemas to incorporate new information that doesn’t fit existing structures.

4.3. Equilibration

The drive for equilibration – a balance between assimilation and accommodation – is the fundamental mechanism of cognitive development in Piaget’s theory. When children encounter information that doesn’t fit their existing schemas (a state of disequilibrium), they are motivated to adjust their thinking to restore balance.

4.4. The Role of Action and Experience

Piaget emphasized that children are not passive recipients of knowledge but active constructors of their understanding. Through physical and mental actions on the environment, children discover regularities, test hypotheses, and build increasingly complex cognitive structures.

5. Piaget’s Research Methods

5.1. The Clinical Interview

Piaget pioneered the use of open-ended clinical interviews to explore children’s thinking. By asking probing questions and presenting children with puzzles or problems, he sought to uncover the reasoning behind their responses.

5.2. Naturalistic Observation

Much of Piaget’s early work involved careful observation of his own children in natural settings. This approach allowed him to document the emergence of new cognitive abilities and the subtle shifts in children’s thinking over time.

5.3. Conservation Tasks

Piaget developed a series of tasks to investigate children’s understanding of conservation – the principle that certain properties of objects remain the same despite changes in appearance. These tasks revealed fundamental differences in logical thinking between younger and older children.

5.4. Perspective-Taking Studies

To explore egocentrism, Piaget designed experiments like the “Three Mountains” task, which assessed children’s ability to imagine how a scene would look from different viewpoints.

6. Implications for Education

6.1. Developmentally Appropriate Practice

Piaget’s theory suggests that educational approaches should be tailored to children’s cognitive level. Curriculum and teaching methods should match the abilities and limitations of children at each developmental stage.

6.2. Active Learning

Piaget’s emphasis on the child as an active constructor of knowledge supports educational approaches that encourage hands-on exploration, experimentation, and discovery learning.

6.3. The Role of Play

Piaget saw play as crucial for cognitive development, particularly in the preoperational stage. Through symbolic play, children practice and consolidate their emerging cognitive skills.

6.4. Social Interaction and Cognitive Conflict

While Piaget focused primarily on individual cognitive development, his later work acknowledged the importance of social interaction in stimulating cognitive growth. Encounters with differing viewpoints can create cognitive conflict, spurring development.

6.5. Constructivist Education

Piaget’s ideas have been influential in the development of constructivist educational approaches, which emphasize student-centered, inquiry-based learning and the active construction of knowledge.

7. Moral Development

7.1. Heteronomous and Autonomous Morality

Piaget proposed that children’s moral reasoning progresses from a “heteronomous” stage (where rules are seen as absolute and unchangeable) to an “autonomous” stage (where rules are understood as social agreements that can be modified).

7.2. Moral Realism

Young children, Piaget observed, tend to judge the morality of actions by their consequences rather than intentions – a phenomenon he called “moral realism.”

7.3. Reciprocity and Cooperation

Piaget argued that peer interactions and cooperative play are crucial for the development of more mature moral reasoning, as they allow children to practice reciprocity and negotiate rules.

8. Physical and Mathematical Concepts

8.1. Object Permanence

Piaget’s work on object permanence in infants revealed the gradual development of the understanding that objects continue to exist when out of sight.

8.2. Conservation

Through his famous conservation tasks, Piaget demonstrated how children’s understanding of quantity, mass, and volume develops over time.

8.3. Classification and Seriation

Piaget investigated the development of logical-mathematical thinking, showing how children’s ability to classify objects and order them in series emerges during the concrete operational stage.

8.4. Spatial Reasoning

His studies on children’s understanding of space, including their ability to represent spatial relationships mentally, influenced theories of spatial cognition.

9. Critiques and Developments

9.1. Age Norms and Individual Differences

Critics have argued that Piaget underestimated the cognitive abilities of young children and that the ages he proposed for various stages are not universal.

9.2. Domain Specificity

Some researchers suggest that cognitive development may be more domain-specific than Piaget’s general stage theory implies, with children showing different levels of ability across different areas.

9.3. Cultural Influences

Cross-cultural studies have revealed variations in the timing and manifestation of cognitive achievements, challenging the universality of Piaget’s stages.

9.4. The Role of Language and Social Interaction

Theorists like Lev Vygotsky emphasized the importance of language and social interaction in cognitive development, aspects that Piaget’s theory initially underplayed.

9.5. Information Processing Approaches

More recent cognitive theories have focused on information processing mechanisms, offering a different perspective on cognitive development than Piaget’s stage theory.

10. Legacy and Ongoing Influence

10.1. Developmental Psychology

Piaget’s work fundamentally shaped the field of developmental psychology, establishing cognitive development as a major area of study.

10.2. Educational Theory and Practice

His theories continue to influence educational approaches worldwide, particularly in early childhood and elementary education.

10.3. Cognitive Science

Piaget’s ideas about the active construction of knowledge have informed research in cognitive science and artificial intelligence.

10.4. Philosophy of Mind

His investigations into the nature of knowledge and its development have had lasting impact on epistemology and philosophy of mind.

10.5. Neuroscience

Recent neuroscientific research has explored the brain mechanisms underlying the cognitive developments Piaget described.

11 Lasting Legacy and Influence

Jean Piaget’s pioneering work on cognitive development has left an indelible mark on psychology, education, and our understanding of how children think and learn. His theory of stage-wise cognitive growth, his emphasis on the child as an active constructor of knowledge, and his innovative research methods revolutionized the study of child development.

While subsequent research has refined and sometimes challenged aspects of Piaget’s theory, his core insights about the qualitative differences in children’s thinking across development and the importance of active exploration in learning remain foundational. His work continues to inspire research and debate across multiple disciplines, from developmental psychology and education to cognitive science and philosophy.

As we face the challenges of education in the 21st century, Piaget’s vision of the child as a curious, active learner remains as relevant as ever. His legacy reminds us of the importance of nurturing children’s natural curiosity, providing rich environments for exploration, and respecting the unique ways that children construct their understanding of the world.

By engaging deeply with Piaget’s ideas, we gain not only a richer understanding of cognitive development but also valuable insights into the nature of knowledge itself. His work invites us to marvel at the extraordinary journey of the human mind as it unfolds from infancy to adulthood, continually constructing and reconstructing its understanding of reality.

As we continue to build on Piaget’s foundation, we are challenged to create educational and developmental environments that truly honor the active, constructive nature of human cognition. In doing so, we can help nurture generations of learners who are not just passive recipients of knowledge, but active, critical thinkers equipped to navigate the complexities of our rapidly changing world.

11.1. Developmental Psychology

Jean Piaget’s groundbreaking theories and research laid the foundation for the modern field of developmental psychology. His work established the study of cognitive development as a central area of inquiry, shaping the questions, methods, and theoretical frameworks that have guided the field for decades. Piaget’s stage theory provided a comprehensive model of intellectual growth from birth to adolescence, offering a roadmap for understanding the qualitative changes in thinking that occur as children mature.

While subsequent research has refined and qualified some aspects of Piaget’s stage model, his core insights about the constructive nature of cognitive development, the importance of active exploration in learning, and the profound differences between child and adult thought continue to inform developmental research today. Piaget’s emphasis on rigorous observational methods and the use of clinical interviews to probe children’s thinking also set new standards for empirical investigation in developmental psychology.

Beyond inspiring an immense body of research directly testing and extending his ideas, Piaget’s work has also served as a springboard for alternative theories and new directions in developmental psychology. For example, information processing theories emerged in part as a reaction to limitations in Piaget’s approach, offering new frameworks for analyzing cognitive change in terms of specific mental processes and strategies.

Neo-Piagetian theories have sought to integrate Piaget’s insights with findings from cognitive psychology, proposing more complex and domain-specific models of development. And sociocultural theories, such as that of Lev Vygotsky, have built on Piaget’s ideas while placing greater emphasis on the role of language, social interaction, and cultural context in shaping cognitive growth.

In each case, Piaget’s work has served as a vital reference point, a foundation upon which subsequent researchers have built in their efforts to understand the mysteries of the developing mind. His legacy is visible not only in the specific theories and findings of developmental psychology but in the enduring commitment to studying cognitive development as a dynamic, constructive process shaped by the interplay of biology, experience, and the active efforts of the child.

11.2. Educational Theory and Practice

Piaget’s work has had a profound and lasting impact on educational theory and practice around the world. His insights into the nature of learning and the developmental constraints on children’s thinking have challenged traditional views of education and inspired new approaches to teaching and curriculum design.

At the heart of Piaget’s educational legacy is a vision of the child as an active, curious learner who constructs knowledge through hands-on exploration and interaction with the environment. This constructivist perspective contrasts sharply with the once-dominant behaviorist view of learning as a passive process of absorbing information from teachers and textbooks.

Piaget’s theory suggests that effective education must be tailored to the child’s developmental level, building on existing cognitive structures and providing opportunities for the child to discover new concepts through active experimentation. This principle of developmentally appropriate practice has become a cornerstone of early childhood education, shaping the design of preschool and primary school curricula that emphasize play, exploration, and the use of concrete materials to support learning.

Piaget’s emphasis on the importance of social interaction and peer dialogue in promoting cognitive growth has also influenced educational practice. Cooperative learning strategies, in which students work together to solve problems and discuss ideas, have their roots in Piagetian theory. So too do instructional approaches that challenge students with cognitive conflicts and encourage them to reflect on their own thinking processes.

In the realm of science and mathematics education, Piaget’s work has been particularly influential. His studies of children’s understanding of physical and logical-mathematical concepts have informed the development of inquiry-based science curricula and the use of manipulatives in math instruction. More broadly, Piaget’s theory has supported the move away from rote learning and memorization towards teaching strategies that foster conceptual understanding and problem-solving skills.

While not all aspects of Piaget’s theory have been fully supported by subsequent research, his central insights about the active, constructive nature of learning continue to shape educational thought and practice. From the design of children’s museums and discovery centers to the growing emphasis on student-centered, project-based learning in schools, Piaget’s legacy is visible in the many ways that educators seek to engage children’s natural curiosity and support their cognitive development.

As educational systems around the world grapple with the challenges of preparing students for an increasingly complex and changing world, Piaget’s ideas remain as relevant as ever. His work reminds us that true learning is not a matter of simply absorbing facts, but of actively constructing knowledge through exploration, experimentation, and critical thinking. By designing educational environments that support this constructive process, we can help children develop the cognitive tools they need to become lifelong learners and productive citizens in the 21st century.

11.3. Cognitive Science and Artificial Intelligence

Piaget’s theories have also had a significant influence on the interdisciplinary field of cognitive science, which emerged in the 1950s to study the mind and its processes. Piaget’s emphasis on the active, constructive nature of cognition and his detailed analyses of the development of mental structures and operations have provided important insights for understanding human intelligence and building intelligent systems.

In the early days of artificial intelligence (AI), researchers drew on Piaget’s work to develop models of learning and problem-solving that mirrored the stage-wise development of children’s thinking. For example, some early AI systems were designed to progress from simple, sensorimotor-like interactions with the environment to more abstract, symbolic reasoning, echoing the sequence of cognitive development described by Piaget.

Piaget’s concepts of assimilation and accommodation have also been influential in AI, inspiring models of machine learning that involve the progressive modification of knowledge structures in response to new data. His emphasis on the importance of active, exploratory learning has informed the development of reinforcement learning algorithms, which allow AI systems to learn from trial-and-error interactions with their environment.

More recently, Piaget’s theory has been a source of inspiration for developmental robotics, a field that seeks to create robots that learn and develop in ways analogous to human children. By building robots that can explore, manipulate, and learn from their environment, researchers hope to gain new insights into the mechanisms of cognitive development and the emergence of intelligence.

Beyond these specific applications, Piaget’s work has contributed to a broader appreciation within cognitive science of the dynamic, adaptive nature of human intelligence. His research demonstrating the qualitative differences in thinking across development has challenged simplistic notions of intelligence as a fixed, unitary trait and highlighted the complex processes of growth and change that underlie cognitive abilities.

At the same time, Piaget’s theory has also served as a foil for alternative approaches in cognitive science. His emphasis on domain-general stages of development, for example, has been challenged by theories that posit more domain-specific and modular cognitive architectures. And his focus on individual cognitive structures has been complemented by research highlighting the importance of social and cultural factors in shaping cognitive development.

Despite these challenges and alternatives, Piaget’s ideas continue to be a vital reference point for cognitive scientists seeking to understand the nature and origins of human intelligence. His pioneering work on the development of mental structures and processes laid the groundwork for much of the research in cognitive science today, and his insights continue to inspire new avenues of inquiry into the workings of the mind.

As cognitive science continues to evolve, integrating insights from fields as diverse as neuroscience, computer science, linguistics, and anthropology, Piaget’s legacy remains central. His vision of the mind as an active, adaptive system that constructs knowledge through interaction with the world is as relevant today as it was a century ago, guiding research on everything from early childhood education to artificial intelligence. By engaging deeply with Piaget’s ideas, cognitive scientists can gain not only a deeper appreciation for the roots of their field, but also new inspiration for exploring the profound mysteries of human cognition.

11.4. Epistemology and Philosophy of Mind

Piaget’s work has had a profound impact on epistemology and the philosophy of mind, challenging traditional views of knowledge and offering new perspectives on the nature of cognitive development. His theory of genetic epistemology, which traced the origins of knowledge from its roots in the sensorimotor actions of infants to the abstract reasoning of adults, has been a major contribution to understanding how we come to know about the world.

Central to Piaget’s epistemology is the idea that knowledge is not a static copy of reality, but an active construction by the knowing subject. He argued that cognitive development proceeds through a process of equilibration, as individuals actively assimilate new information into existing cognitive structures and accommodate those structures to fit new experiences. This constructivist view of knowledge acquisition has been highly influential, challenging empiricist and nativist theories that see knowledge as either imprinted by experience or predetermined by innate structures.

Piaget’s stage theory also introduced a new way of thinking about the nature of intelligence and its development over time. By demonstrating the qualitative differences in thinking between children and adults, Piaget challenged the idea that intelligence is a unitary, fixed trait. Instead, he proposed that cognitive abilities develop through a series of transformations, each characterized by distinct logical structures and operations.

This view has important implications for the philosophy of mind, suggesting that mental states and processes are not static entities but dynamic systems that evolve over the course of development. Piaget’s work has inspired philosophical investigations into the nature of mental representation, the role of action in shaping thought, and the relationship between individual cognitive development and the growth of scientific knowledge.

Piaget’s emphasis on the active, constructive nature of cognition has also resonated with philosophers who see the mind as fundamentally embodied and embedded in the world. His research on the sensorimotor origins of intelligence highlights the close connection between perception, action, and thought, a theme that has been taken up by contemporary embodied and enactive approaches to cognition.

At the same time, Piaget’s theory has also been a source of philosophical critique and debate. His claims about the universality and invariant sequence of developmental stages have been questioned, as have his assumptions about the domain-generality of cognitive structures. Philosophers have also raised questions about the epistemological status of Piaget’s theory itself, noting the challenges of empirically verifying claims about the deep structures of thought.

Despite these critiques, Piaget’s ideas continue to be a vital source of inspiration and debate in epistemology and the philosophy of mind. His genetic epistemology remains a powerful framework for understanding the origins and development of knowledge, while his constructivist theory of cognitive development continues to shape discussions about the nature of intelligence, mental representation, and the relationship between mind and world.

As philosophers grapple with the profound questions of how we come to know and what it means to think, Piaget’s legacy offers a rich source of insights and provocations. By engaging deeply with his ideas, philosophers can gain new perspectives on the nature of mind and knowledge, and new appreciation for the complex processes of cognitive development that shape our understanding of the world.

11.5. Influence on Neuroscience

In recent years, Piaget’s theory of cognitive development has also begun to influence research in neuroscience, as scientists seek to understand the brain mechanisms underlying the cognitive changes he described. While Piaget’s work was based primarily on behavioral observations, advances in brain imaging and other neuroscientific methods have opened new avenues for exploring the neural substrates of cognitive development.

One area where Piaget’s ideas have been particularly relevant is in the study of executive functions – the cognitive control processes that allow us to plan, reason, and regulate our behavior. Piaget’s research on the development of logical reasoning and problem-solving skills in children has provided a valuable framework for understanding the emergence of these abilities, and neuroscientists have begun to investigate the brain systems that support their development.

For example, studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have shown that the prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain associated with higher-order cognitive functions, undergoes significant changes in activity and connectivity over the course of development. These changes parallel the cognitive advances described by Piaget, with the prefrontal cortex becoming increasingly involved in tasks requiring cognitive control and abstract reasoning as children move into adolescence and adulthood.

Piaget’s concept of schema – the mental structures that organize our knowledge and guide our interactions with the world – has also found resonance in neuroscience. Researchers have begun to explore how schemas are represented in the brain, and how they evolve with learning and experience. Some studies suggest that schemas are encoded in distributed networks of neurons that become increasingly interconnected and refined over development, reflecting the progressive elaboration and differentiation of cognitive structures described by Piaget.

Piaget’s emphasis on the role of active exploration and physical interaction with the environment in driving cognitive development has also been supported by neuroscientific research. Studies have shown that motor activity and sensory exploration are crucial for the development of brain systems involved in spatial cognition, object representation, and problem-solving. This aligns with Piaget’s view of the sensorimotor stage as a foundational period in which infants construct their understanding of the world through active engagement with their surroundings.

As neuroscience continues to advance, Piaget’s theory is likely to remain a valuable source of hypotheses and insights for researchers seeking to understand the brain bases of cognitive development. By combining Piaget’s detailed behavioral observations with cutting-edge neuroscientific methods, researchers can begin to bridge the gap between the psychological and biological levels of analysis, and gain a more integrated understanding of how the mind and brain develop over time.

At the same time, neuroscientific research may also help to refine and extend Piaget’s theory, by revealing brain mechanisms and processes that were not accessible to him through behavioral observation alone. For example, research on the developing brain may help to clarify the nature of the cognitive restructuring that occurs at key transition points in Piaget’s stage model, or shed light on the neural mechanisms underlying the assimilation-accommodation process that drives cognitive growth.

Ultimately, the integration of Piagetian theory with neuroscience offers a promising avenue for advancing our understanding of cognitive development and the complex interplay of biology and experience that shapes the emergence of the mind. As researchers continue to explore this intersection, Piaget’s legacy is likely to remain a vital touchstone, inspiring new questions, methods, and insights into the mysteries of the developing brain.

12 Influence

The legacy of Jean Piaget’s work on cognitive development is vast and enduring, spanning multiple disciplines and continuing to shape our understanding of how the mind grows and changes over the lifespan. From developmental psychology and education to cognitive science, artificial intelligence, and neuroscience, Piaget’s ideas have proven remarkably generative, offering a framework for investigating the origins and development of knowledge that continues to guide research and practice today.

At the heart of Piaget’s legacy is a profound respect for the active, constructive nature of the developing mind. His theory challenged prevailing views of children as mere passive recipients of knowledge, instead portraying them as curious, inventive thinkers actively engaged in making sense of their world. This constructivist vision has had a transformative impact on fields from education to epistemology, leading to new appreciation for the role of exploration, experimentation, and self-directed learning in cognitive development.

Piaget’s stage theory, while not without its critics, offered a powerful model of the qualitative changes in thinking that occur as children grow, and a roadmap for understanding the logical structures and operations that underlie intelligent thought. His detailed observations of children’s reasoning in domains from moral judgment to mathematical understanding remain a treasure trove for researchers seeking to chart the complex contours of cognitive growth.

Beyond its scientific impact, Piaget’s work has also had a profound influence on educational practice, inspiring new approaches to teaching and learning that emphasize active engagement, hands-on exploration, and respect for children’s natural curiosity and drive to understand. From the design of preschool classrooms to the development of innovative science and math curricula, Piaget’s insights continue to shape the way we think about education and its role in supporting healthy cognitive development.

As research in fields from cognitive science to neuroscience continues to advance, Piaget’s theory remains a vital touchstone, offering a rich source of hypotheses, methods, and insights for investigating the mysteries of the mind. While some aspects of his theory have been challenged or refined in light of new evidence, the core insights of his constructivist approach – the emphasis on the active, adaptive nature of cognition, the importance of self-directed exploration and social interaction in learning, and the profound transformations that mark the passage from infancy to adulthood – continue to guide and inspire researchers across a range of disciplines.

Looking ahead, the integration of Piagetian theory with new methods and findings from fields like neuroscience and artificial intelligence promises to yield exciting new discoveries about the nature and origins of human cognition. By combining Piaget’s keen observations of the developing mind with cutting-edge tools for probing the brain and modeling intelligent systems, researchers are poised to make significant advances in our understanding of how the mind grows and changes over time.

At the same time, Piaget’s legacy also serves as a reminder of the enduring importance of careful, systematic observation and a deep respect for the developing child as a key source of insight into the workings of the mind. As we continue to grapple with the profound challenges of education in the 21st century, from closing achievement gaps to preparing students for an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world, Piaget’s vision of the child as an active, curious learner offers a powerful starting point for designing learning environments that truly nurture the full potential of every student.

Ultimately, the legacy of Jean Piaget’s work on cognitive development is a testament to the power of a great scientific theory to illuminate, inspire, and transform our understanding of the world and ourselves. By engaging deeply with his ideas and building on his insights, we can continue to unlock the mysteries of the developing mind and create educational and societal conditions that support the flourishing of human intelligence in all its wondrous diversity and potential. As we move forward in this endeavor, we can be grateful for the enduring legacy of a pioneering thinker whose curiosity, creativity, and deep commitment to understanding the mind of the child continue to light the way.

Influential Psychologists

Bibliography

1. Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press.

– This seminal work outlines Piaget’s observations of infant development and introduces his theory of sensorimotor intelligence.

2. Piaget, J. (1954). The Construction of Reality in the Child. New York: Basic Books.

– Piaget explores how children develop concepts of object permanence, space, causality, and time during the sensorimotor period.

3. Piaget, J. (1964). Six Psychological Studies. New York: Vintage Books.

– This collection includes essays on various aspects of child development, including play, imitation, and the formation of symbolic thought.

4. Piaget, J. (1965). The Moral Judgment of the Child. New York: Free Press.

– Piaget investigates children’s understanding of moral concepts, rules, and justice, proposing a developmental theory of moral reasoning.

5. Piaget, J. (1970). Genetic Epistemology. New York: Columbia University Press.

– This work presents Piaget’s theory of knowledge development, linking biological adaptation to cognitive growth.

6. Piaget, J. (1971). Biology and Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

– Piaget explores the relationship between biological structures and cognitive processes, emphasizing the role of action in knowledge construction.

7. Piaget, J. (1972). The Psychology of Intelligence. London: Routledge.

– This book provides an overview of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, including detailed descriptions of the four main stages.

8. Piaget, J. (1977). The Development of Thought: Equilibration of Cognitive Structures. New York: Viking.

– Piaget elaborates on his concept of equilibration as the driving force behind cognitive development.

9. Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1969). The Psychology of the Child. New York: Basic Books.

– This comprehensive summary of Piaget’s theory, co-authored with his long-time collaborator Bärbel Inhelder, covers all major aspects of child cognitive development.

10. Flavell, J. H. (1963). The Developmental Psychology of Jean Piaget. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

– Flavell provides a detailed analysis and interpretation of Piaget’s work, making it more accessible to English-speaking audiences.

11. Ginsburg, H., & Opper, S. (1988). Piaget’s Theory of Intellectual Development (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

– This book offers a clear exposition of Piaget’s theory, including practical applications and critical evaluations.

12. Beilin, H., & Pufall, P. B. (Eds.). (1992). Piaget’s Theory: Prospects and Possibilities. Hillsdale, NJ: Psychology Press.

– A collection of essays examining the impact and future directions of Piagetian theory in various fields of study.

13. Muller, U., Carpendale, J. I. M., & Smith, L. (Eds.). (2009). The Cambridge Companion to Piaget. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

– This comprehensive volume covers Piaget’s life, work, and influence, with contributions from leading scholars in the field.

14. Sternberg, R. J., & Berg, C. A. (Eds.). (1992). Intellectual Development. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

– This book examines various approaches to intellectual development, including Piagetian theory and its alternatives.

15. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

– Vygotsky’s work, often contrasted with Piaget’s, emphasizes the role of social interaction and culture in cognitive development.

16. Donaldson, M. (1978). Children’s Minds. London: Fontana Press.

– Donaldson critically examines Piaget’s methods and conclusions, suggesting that children’s abilities may be greater than Piaget proposed.

17. Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a Theory of Instruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

– Bruner, influenced by Piaget, presents his own ideas on cognitive development and educational practice.

18. Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1992). Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

– Karmiloff-Smith proposes a neo-Piagetian approach to cognitive development, integrating Piaget’s ideas with more recent findings in cognitive science.

19. Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

– Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, while distinct from Piaget’s work, builds on the idea of qualitative differences in cognitive abilities.

20. Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A. N., & Kuhl, P. K. (1999). The Scientist in the Crib: What Early Learning Tells Us About the Mind. New York: William Morrow.

– This book presents recent research on infant cognition, both building upon and challenging aspects of Piaget’s theory.

0 Comments