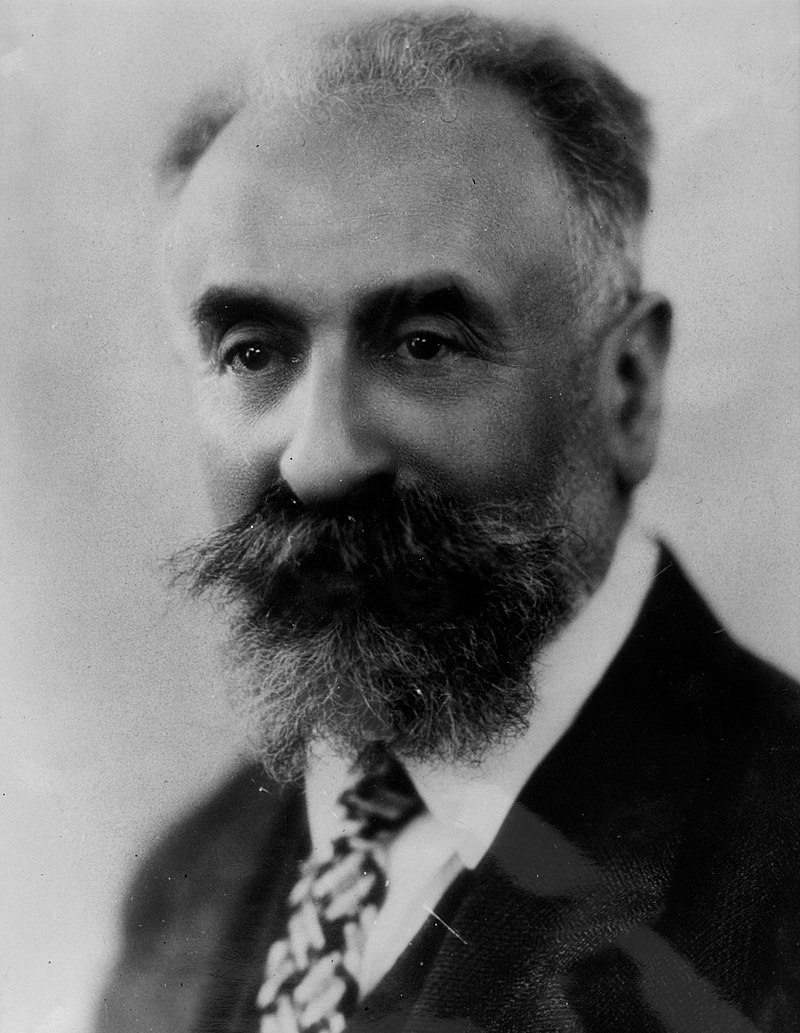

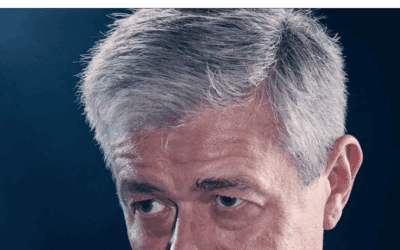

Portrait de Marcel Mauss appartenant à la collection de 15 portraits de sociologues constituée par la Société des Amis du Centre d’Études Sociologiques (SACES représenté par son ex-président, M. Daniel Derivry). L’ensemble de la collection est la propriété de la Bibliothèque de sciences humaines et sociales Descartes CNRS (UMS 3036)

1. Who Was Marcel Mauss?

Marcel Mauss (1872-1950) was a pioneering French sociologist and anthropologist, best known for his influential essay “The Gift” (1925) and his role in shaping the development of social theory in the early 20th century. A nephew and close collaborator of Émile Durkheim, Mauss played a key role in the establishment of sociology and anthropology as distinct academic disciplines in France, and his work had a profound impact on later thinkers such as Claude Lévi-Strauss, Pierre Bourdieu, and Maurice Godelier.

Born into a Jewish family in Épinal, France, Mauss studied philosophy and the history of religion before turning to sociology under the influence of his uncle Durkheim. He was a prolific scholar, publishing numerous books and articles on topics ranging from prayer and sacrifice to the origins of money and the category of the person. However, his most famous and enduring work remains “The Gift,” a groundbreaking study of the social and spiritual significance of gift exchange in traditional societies.

In “The Gift,” Mauss argues that the exchange of gifts is a fundamental social phenomenon that creates and maintains bonds of obligation and solidarity between individuals and groups. Drawing on ethnographic data from Polynesia, Melanesia, and the Pacific Northwest, he shows how gift-giving is governed by complex rules and rituals that serve to establish relationships of reciprocity, hierarchy, and alliance. For Mauss, the gift is not merely an economic transaction, but a total social fact that involves the whole of society and its institutions.

Mauss’s analysis of the gift had far-reaching implications for social theory, challenging utilitarian and individualistic conceptions of human behavior and highlighting the importance of symbolic exchange and collective representations in social life. His work helped to lay the foundations for a new understanding of the nature of social bonds and the roots of human solidarity, influencing subsequent developments in anthropology, sociology, and political philosophy.

Beyond his scholarly contributions, Mauss was also deeply engaged in political and social issues of his time. A committed socialist and cooperativist, he was active in the French labor movement and worked to promote international understanding and solidarity in the aftermath of World War I. He was a founding member of the Institut d’ethnologie and played a key role in the establishment of the Musée de l’Homme in Paris.

Mauss’s life and work were marked by a deep commitment to the values of humanism, reason, and social justice. His intellectual legacy continues to inspire and inform research across the social sciences, as scholars grapple with the enduring questions of what holds societies together and how to build a more just and solidaristic world.

2. The Gift and the Obligations of Exchange

At the heart of Mauss’s work is the concept of the gift – a form of exchange that he saw as fundamental to the creation and maintenance of social bonds in traditional societies. In contrast to modern economic transactions, which are typically impersonal and focused on the immediate transfer of goods or services, gift exchange involves a complex web of obligations and reciprocities that bind individuals and groups together over time.

For Mauss, the gift is not a unilateral act of generosity, but a total social phenomenon that engages the whole of society and its institutions. When one person gives a gift to another, they are not merely transferring an object, but also a part of themselves – their mana, or spiritual essence. This creates a powerful bond between giver and receiver, one that must be acknowledged and reciprocated in order to maintain social harmony and balance.

Mauss identifies three key obligations that govern gift exchange: the obligation to give, the obligation to receive, and the obligation to reciprocate. In traditional societies, these obligations are often highly ritualized and infused with spiritual significance. Failure to fulfill them can result in a loss of face, social ostracism, or even supernatural retribution.

The obligation to give is rooted in the idea that individuals have a social and moral duty to share their wealth and resources with others. This is not simply a matter of altruism or generosity, but a fundamental requirement of social life. By giving gifts, individuals demonstrate their commitment to the group and their willingness to subordinate their own interests to the collective good.

The obligation to receive is equally important, as it demonstrates respect for the giver and acknowledgement of the social bond being created. To refuse a gift is to reject the relationship being offered and to risk causing offense or insult. At the same time, accepting a gift also means accepting the obligations and reciprocities that come with it.

Finally, the obligation to reciprocate is what gives gift exchange its dynamic and cyclical character. Having received a gift, the recipient is now obliged to return the favor at some point in the future, often with a gift of equal or greater value. This creates an ongoing cycle of exchange that serves to reinforce social bonds and maintain the balance of power and prestige within the community.

Mauss’s analysis of gift exchange highlights the deeply social and symbolic nature of economic transactions in traditional societies. Far from being a simple matter of utilitarian calculation, exchange is embedded in a complex web of cultural meanings and moral obligations. It serves to create and maintain relationships, establish hierarchies and alliances, and ensure the continuity of social life across generations.

At the same time, Mauss also recognizes the potential for gift exchange to become a source of social tension and conflict. The obligations of reciprocity can create rivalries and power struggles, as individuals seek to outdo one another in the generosity and splendor of their gifts. In some cases, this can lead to the emergence of a “gift economy” in which social status and prestige are determined by one’s ability to give and receive gifts, rather than by more substantive measures of worth or merit.

Despite these potential downsides, Mauss sees gift exchange as a fundamentally positive and integrative force in human societies. By creating bonds of reciprocity and solidarity, it helps to counteract the atomizing and alienating tendencies of modern individualism. In a world increasingly dominated by the impersonal logic of the market, Mauss’s work serves as a reminder of the enduring importance of social and symbolic exchange in human life.

3. The Social Origins of the Person

Mauss’s work on gift exchange is part of a broader inquiry into the social and cultural origins of human thought and experience. In his essay “A Category of the Human Mind: The Notion of Person; the Notion of Self” (1938), he argues that the very concept of the individual as a distinct, autonomous entity is a product of specific historical and cultural conditions, rather than a universal given.

Drawing on ethnographic and historical evidence, Mauss traces the evolution of the concept of the person from its earliest origins in tribal societies to its modern incarnation in Western individualism. In traditional societies, he argues, the notion of the person is deeply embedded in social and cosmological frameworks, with individuals deriving their identity and status from their position within a complex web of kinship, clan, and spiritual relationships.

In these contexts, the person is not conceived as a separate, self-contained entity, but rather as a node in a larger network of social and supernatural forces. The boundaries between self and other, individual and group, are fluid and permeable, with the actions and experiences of one person often seen as intimately connected to those of others.

Mauss shows how this social conception of the person is reflected in various cultural practices and institutions, from naming conventions and initiation rites to systems of property and inheritance. In many traditional societies, for example, individuals do not own property in the modern sense, but rather hold it in trust for the larger group, with ownership passing from one generation to the next through complex rules of kinship and descent.

With the rise of ancient civilizations and the emergence of more complex forms of social organization, Mauss argues, the concept of the person begins to take on a more individualized and abstract character. In ancient Greece and Rome, for example, the notion of the citizen emerges as a legal and political category, with individuals defined by their rights and duties within the larger polity.

However, it is only with the advent of Christianity and the rise of modern Western societies that the concept of the person as a distinct, autonomous individual fully emerges. For Mauss, this development is closely tied to the rise of capitalism, with its emphasis on individual property rights, market exchange, and the separation of the economic from the social and political spheres.

At the same time, Mauss is critical of the extreme individualism of modern Western societies, which he sees as a source of social fragmentation and alienation. By eroding traditional forms of social solidarity and emphasizing individual self-interest over collective well-being, modern individualism threatens to undermine the very foundations of human sociality and cooperation.

In this context, Mauss’s work on the social origins of the person serves as a powerful reminder of the ways in which our understanding of ourselves and our place in the world is shaped by the larger social and cultural contexts in which we live. By highlighting the historical and cultural specificity of the modern concept of the individual, he challenges us to rethink our assumptions about the nature of selfhood and to explore alternative ways of imagining the relationship between the individual and the collective.

At the same time, Mauss’s analysis also points to the enduring importance of social bonds and reciprocities in human life, even in the face of the atomizing tendencies of modern individualism. By showing how the very notion of the person is rooted in social relationships and cultural meanings, he reminds us of the fundamental interdependence of human beings and the need to cultivate forms of solidarity and cooperation that can transcend the narrow confines of the individual self.

4. Influence and Legacy

Mauss’s work had a profound impact on the development of social theory in the 20th century, influencing a wide range of thinkers and disciplines. His analysis of gift exchange and the social origins of the person challenged prevailing assumptions about the nature of human behavior and social organization, and helped to lay the foundations for a new understanding of the relationship between culture, economy, and society.

In anthropology, Mauss’s ideas were taken up and developed by a number of influential thinkers, including Claude Lévi-Strauss, who drew on Mauss’s work to develop his structural analysis of kinship and myth, and Marshall Sahlins, who extended Mauss’s insights into the nature of reciprocity and exchange in his studies of Polynesian societies. Mauss’s emphasis on the symbolic and cultural dimensions of economic life also influenced later generations of economic anthropologists, such as Karl Polanyi and Maurice Godelier.

In sociology, Mauss’s work helped to shape the development of a more culturally and historically informed approach to the study of social phenomena. His insights into the social origins of the person and the importance of collective representations in shaping individual experience were taken up by thinkers such as Maurice Halbwachs and Pierre Bourdieu, who developed influential theories of social memory and habitus.

Mauss’s political and ethical commitments also had a lasting impact on social thought, particularly in France. His involvement in the cooperative movement and his critiques of extreme individualism and market capitalism influenced later generations of socialist and left-wing thinkers, such as Georges Bataille and the Situationist International. At the same time, his emphasis on the importance of social solidarity and the moral obligations of reciprocity resonated with a range of political and philosophical traditions, from communitarianism to Catholic social teaching.

Beyond his immediate intellectual and political influence, Mauss’s work continues to inspire and inform contemporary debates on a range of issues, from the nature of social bonds and the limits of economic rationality to the possibilities for building more just and cooperative forms of human society. His insights into the social and cultural dimensions of economic life have taken on renewed relevance in an era of globalization and financialization, as scholars and activists seek to develop alternative models of exchange and social organization that can resist the atomizing and alienating tendencies of neoliberal capitalism.

At the same time, Mauss’s emphasis on the importance of reciprocity and social solidarity in human life continues to resonate with contemporary efforts to build more inclusive and participatory forms of democracy and civil society. His vision of a society based on the moral obligations of gift exchange and mutual aid, rather than the narrow pursuit of individual self-interest, offers a powerful alternative to the dominant ideologies of our time, and a reminder of the enduring possibilities for human cooperation and solidarity.

As we grapple with the challenges and crises of the 21st century, from climate change and rising inequality to the erosion of social trust and the fragmentation of communities, Mauss’s work offers a rich resource for reimagining the possibilities of human sociality and cooperation. By reminding us of the deep roots of human solidarity and the enduring importance of social and symbolic exchange, he invites us to think beyond the narrow confines of individual self-interest and to explore new forms of reciprocity and mutual aid that can help to build a more just and sustainable world.

Conclusion

The work of Marcel Mauss represents a seminal contribution to the development of social theory in the 20th century, and a powerful challenge to the individualistic and utilitarian assumptions that have long dominated Western thought. Through his analysis of gift exchange and the social origins of the person, Mauss helped to lay the foundations for a new understanding of the cultural and symbolic dimensions of human life, and the ways in which social bonds and reciprocities shape individual experience and collective action.

Mauss’s insights into the nature of social solidarity and the moral obligations of reciprocity continue to resonate with contemporary debates and struggles, from the search for alternative forms of economic organization to the effort to build more inclusive and participatory forms of democracy. His emphasis on the importance of social and symbolic exchange in human life offers a powerful counterpoint to the atomizing and alienating tendencies of modern individualism, and a reminder of the enduring possibilities for human cooperation and mutual aid.

At the same time, Mauss’s work also highlights the complex and contested nature of social bonds and reciprocities, and the ways in which they can become sources of power, inequality, and conflict as well as solidarity and cooperation. His analysis of the gift as a total social phenomenon, embedded in a web of cultural meanings and moral obligations, challenges us to think beyond simplistic dichotomies of altruism and self-interest, and to grapple with the deep ambivalences and contradictions that shape human sociality.

As we confront the challenges and crises of our own time, Mauss’s legacy offers a rich resource for reimagining the possibilities of human solidarity and cooperation. By reminding us of the social and cultural roots of individual experience and collective action, he invites us to think beyond the narrow confines of the self and to explore new forms of reciprocity and mutual aid that can help to build a more just and sustainable world. In doing so, he challenges us to embrace the full complexity and richness of human social life, and to recognize the enduring importance of the ties that bind us together as individuals and as members of larger communities and societies.

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

0 Comments