“If I had a friend and loved him because of the benefits which this brought me and because of getting my own way, then it would not be my friend that I loved but myself. I should love my friend on account of his own goodness and virtues and account of all that he is in himself. Only if I love my friend in this way do I love him properly.”

― Meister Eckhart, Selected Writings

The relationship between the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart and the Catholic Church can be seen as a powerful metaphor for the relationship between the ego and the unconscious in the human psyche. Just as the Church, representing the conscious, rational, and institutional aspects of spirituality, sought to control and regulate Eckhart’s mystical teachings, the ego often attempts to assert its dominance over the unconscious, the source of deep spiritual and emotional experiences.

Eckhart’s life and thought highlight the inevitable tension between the structured, dogmatic aspects of religion and the transformative, experiential dimensions of mysticism. Similarly, the ego, which plays a crucial role in navigating the demands of everyday life and maintaining a sense of identity, often resists the powerful currents of the unconscious, which can challenge its assumptions and disrupt its carefully constructed sense of control.

However, just as the Church ultimately cannot suppress the emergence of mystical experiences and insights, the ego cannot fully control the forces of the unconscious. The spiritual and emotional energies that guide and shape our lives often operate beyond the boundaries of rational understanding and conscious volition.

By exploring the parallels between Eckhart’s relationship with the Church and the ego’s relationship with the unconscious, we can gain valuable insights into the nature of spiritual growth, psychological integration, and the challenges of reconciling the demands of institutional religion with the transformative power of mystical experience.

Meister Eckhart’s Ideas:

Meister Eckhart’s Concept of the Gottheit and the Process of Holding:

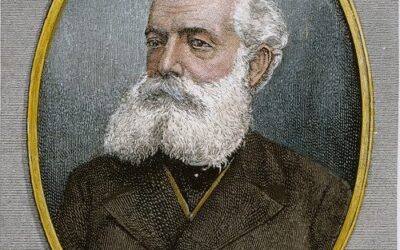

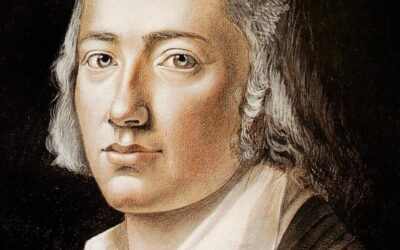

Meister Eckhart, a 13th-century German theologian and mystic, developed a unique and profound understanding of the divine that centered on the concept of the Gottheit, or “Godhead.” For Eckhart, the Gottheit represented the deepest, most ineffable reality of God, beyond all names, forms, and attributes.

In Eckhart’s theology, the Gottheit is the source and ground of all being, the “silent desert” from which all things emerge and to which all things return. It is the absolute unity and simplicity that underlies the multiplicity and diversity of the created world.

To experience the Gottheit, Eckhart taught that one must engage in a process of “holding” or “letting go.” This involves a radical detachment from all things, including one’s own ego, desires, and conceptions of God. By emptying oneself of all attachments and images, one creates a space of inner stillness and receptivity in which the Gottheit can reveal itself.

Eckhart often used the metaphor of the “virgin womb” to describe this state of pure potentiality and openness. Just as the Virgin Mary held the fullness of God within her womb, so too can the human soul become a vessel for the divine by letting go of all that is not God.

The Concepts of Poverty and Images in Eckhart’s Thought:

Two key concepts in Eckhart’s teachings on the process of holding are poverty and images. For Eckhart, poverty is not simply material deprivation, but rather a state of spiritual detachment and emptiness. It is the willingness to let go of all possessions, both external and internal, in order to make room for God.

Eckhart often spoke of the “poor in spirit,” those who have stripped themselves of all worldly attachments and desires and have become utterly receptive to the divine. He saw this spiritual poverty as the highest form of human perfection, the state in which the soul is most fully united with God.

Images, in Eckhart’s thought, refer to all the mental and conceptual structures that we use to understand and relate to God. These can include theological doctrines, devotional practices, and even our own personal experiences of the divine.

While Eckhart acknowledged the value of images in the spiritual life, he also saw them as potential obstacles to the direct experience of the Gottheit. Images, he argued, can become idols that we cling to and worship, rather than doorways that lead us beyond themselves to the ineffable reality of God.

To truly experience the Gottheit, Eckhart taught that one must be willing to let go of all images and concepts, even those that seem most holy and true. This can be a challenging and disorienting process, as it requires a radical trust in the unknown and the unknowable.

To be full of things is to be empty of God. To be empty of things is to be full of God. The eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me.

-Meister Eckhart

The Goal of Union with the Gottheit:

The ultimate goal of Eckhart’s spiritual path is union with the Gottheit, the complete dissolution of the individual self in the infinite reality of God. This is not a loss of identity, but rather a discovery of one’s truest and deepest self, the “spark of the soul” that is always already one with the divine.

For Eckhart, this union is not something that can be achieved through human effort or striving, but rather a gift of grace that comes from God alone. By engaging in the process of holding and letting go, the soul creates the conditions for this grace to flow freely and transform the whole of one’s being.

Eckhart’s vision of union with the Gottheit is a daring and radical one, as it challenges many traditional conceptions of God and the spiritual life. It invites us to let go of our attachment to images, concepts, and experiences, and to trust in the silent, ineffable reality that underlies all things.

At the same time, Eckhart’s teachings are deeply affirming of the human capacity for spiritual transformation and union with the divine. They remind us that, at the deepest level of our being, we are always already one with God, and that the journey of the spiritual life is a journey of discovering and manifesting this unity in all aspects of our lives.

Implications for Christianity:

Meister Eckhart’s teachings on the Gottheit, poverty, and images have profound implications for contemporary spirituality and mysticism. In a world that is often dominated by materialism, consumerism, and the pursuit of ego-driven goals, Eckhart’s call to radical detachment and spiritual poverty is a powerful challenge and invitation.

By letting go of our attachments to possessions, status, and even our own self-image, we create space for a deeper and more authentic experience of the divine. We discover that our true identity is not based on what we have or what we do, but rather on our inherent unity with the source and ground of all being.

Eckhart’s Relationship with the Church:

Meister Eckhart was a devoted member of the Dominican Order and a respected theologian and teacher throughout much of his life. However, his mystical teachings, which emphasized the direct experience of God and the unity of the soul with the divine, often pushed the boundaries of orthodox thought and brought him into conflict with Church authorities.

Eckhart taught that the ultimate goal of the spiritual life was to achieve a state of union with God, in which the individual soul is completely detached from the “image” world and united with the divine essence. He emphasized the importance of inner transformation and the cultivation of spiritual virtues such as humility, detachment, and love.

While these teachings inspired many spiritual seekers, they also raised concerns among some Church officials, who feared that Eckhart’s ideas could lead to pantheism, heresy, or a rejection of Church authority. In 1326, the Archbishop of Cologne initiated an investigation into Eckhart’s teachings, and in 1327, Pope John XXII issued a bull condemning 28 propositions drawn from Eckhart’s writings.

Eckhart attempted to defend his ideas and argued that his teachings were consistent with Church doctrine, but he died in 1328 before his trial could be concluded. In 1329, the Pope issued a second bull condemning an additional 17 propositions from Eckhart’s writings.

Despite this condemnation, Eckhart’s ideas continued to influence Christian spirituality, particularly among mystics and spiritual seekers. In the 20th century, there was a renewed interest in Eckhart’s thought, and in 1985, the Dominican Order formally requested that the Vatican re-examine Eckhart’s case. In 2010, Pope John Paul II officially rehabilitated Eckhart, acknowledging the orthodoxy of his teachings and paving the way for his eventual canonization.

Timeline of Meister Eckhart’s Life:

c. 1260: Eckhart is born in Hochheim, near Gotha, Germany.

c. 1275: Eckhart enters the Dominican Order.

c. 1277-1286: Eckhart studies at the University of Paris.

c. 1286-1294: Eckhart teaches theology at the University of Paris.

c. 1294-1298: Eckhart serves as Prior of the Dominican monastery in Erfurt, Germany.

c. 1298-1302: Eckhart serves as Provincial Superior of the Dominican Order in Saxony.

c. 1302-1311: Eckhart teaches theology at the University of Paris and serves as Provincial Superior of the Dominican Order in Bohemia.

c. 1311-1313: Eckhart serves as Provincial Superior of the Dominican Order in Teutonia.

c. 1313-1323: Eckhart teaches theology and preaches in Strasbourg, Frankfurt, and Cologne.

1326: The Archbishop of Cologne initiates an investigation into Eckhart’s teachings.

1327: The Pope issues a bull condemning 28 propositions drawn from Eckhart’s writings.

1328: Eckhart dies in Avignon, France, before his trial is concluded.

1329: The Pope issues a second bull condemning 17 additional propositions from Eckhart’s writings.

The Ego and the Unconscious:

The tension between Eckhart and the Church can be seen as a reflection of the broader tension between the ego and the unconscious in the human psyche. The ego, which represents the conscious, rational, and individual aspects of the self, seeks to maintain control and stability in the face of the vast, mysterious, and often threatening forces of the unconscious.

Just as the Church sought to regulate and contain Eckhart’s mystical experiences and teachings, the ego attempts to impose structure and order on the chaotic and irrational energies of the unconscious. The ego fears that surrendering to these forces could lead to a loss of identity, a dissolution of boundaries, or a descent into madness.

However, just as Eckhart’s mystical insights could not be fully suppressed by the Church, the unconscious cannot be entirely controlled by the ego. The spiritual and emotional depths of the psyche continue to exert a powerful influence on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, even when we are not consciously aware of them.

In fact, attempts to repress or deny the unconscious can often lead to psychological and spiritual imbalances, as the unacknowledged aspects of the self seek expression through symptoms, conflicts, and crises. Just as the Church’s condemnation of Eckhart did not prevent the spread of his ideas, the ego’s efforts to suppress the unconscious can paradoxically give it more power and influence.

The Path of Integration:

The ultimate goal of both spiritual and psychological growth is not to eliminate the tension between the ego and the unconscious, but rather to foster a more harmonious and integrated relationship between these two aspects of the self.

This process of integration requires a willingness to acknowledge and engage with the unconscious, to listen to its messages and insights, and to incorporate its wisdom into the conscious life of the ego. Just as the Church eventually came to recognize the value of Eckhart’s mystical teachings, the ego must learn to embrace the transformative power of the unconscious and to allow itself to be guided by its deeper spiritual and emotional currents.

This path of integration is not always easy or comfortable, as it requires a surrender of the ego’s illusions of control and a confrontation with the shadow aspects of the self. However, it is only by embracing the full complexity and depth of the psyche that we can achieve genuine wholeness, authenticity, and spiritual growth.

Meister Eckhart’s life and teachings offer a powerful example of the challenges and rewards of the mystical path, as well as the inevitable tensions that arise between the institutional and experiential dimensions of spirituality. His relationship with the Church can be seen as a metaphor for the ego’s relationship with the unconscious, highlighting the struggle between the desire for control and the need for surrender.

The key is to find a balance between the conscious and the unconscious, the institutional and the experiential, the structured and the spontaneous. By honoring both the ego and the unconscious, and by cultivating a relationship of mutual respect and dialogue between them, we can create a more dynamic and inclusive vision of spirituality and psychology.

The Church’s Ambivalence Towards Mysticism:

The Catholic Church’s relationship with Christian mysticism has been marked by a deep ambivalence throughout history. On the one hand, the Church has officially recognized and celebrated many mystics as saints, acknowledging the value and authenticity of their spiritual experiences and teachings. Figures like St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Avila, and St. Francis of Assisi have been held up as models of Christian faith and devotion, and their writings have been studied and revered by generations of believers.

The Catholic Church’s relationship with Christian mysticism has been marked by a deep ambivalence throughout history. On the one hand, the Church has officially recognized and celebrated many mystics as saints, acknowledging the value and authenticity of their spiritual experiences and teachings. Figures like St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Avila, and St. Francis of Assisi have been held up as models of Christian faith and devotion, and their writings have been studied and revered by generations of believers.

On the other hand, the Church has also viewed mystical experiences and teachings with suspicion and even hostility, particularly when they challenge traditional religious authority or doctrinal interpretations. Mystics like Meister Eckhart, who emphasized the direct experience of God and the unity of the soul with the divine, have often been accused of heresy, pantheism, or subjectivism, and have faced persecution and condemnation from Church authorities.

This ambivalence reflects a deeper tension within the Church between the institutional and the charismatic, the orthodox and the experiential. As an institution, the Church seeks to maintain doctrinal clarity, moral guidance, and organizational stability, and it often sees mystical experiences and teachings as a threat to these goals. Mystics, by contrast, prioritize the direct, unmediated encounter with the divine, and they often challenge established norms and hierarchies in pursuit of spiritual truth and authenticity.

The Church’s ambivalence towards mysticism can also be seen in its relationship with modern figures like Carl Jung, who explored the spiritual and psychological dimensions of human experience in ways that both resonated with and challenged traditional Christian thought. The church both blessed and condemned Jung, even though he was indifferent to their opinion of him. Every few years a Catholic theologian will try and remind Catholics not to be Jungian we Jung starts to get popular with the clergy.

While some Catholic thinkers have embraced Jung’s ideas as a valuable bridge between psychology and spirituality, others have criticized his work as a form of neo-paganism or relativism that undermines the unique truth claims of Christianity. Usually these writers, like Richard Knoll have to mis read Jungian obvious metaphor and allegory as literal statements to arrive at these absurd propositions.

The Need for a More Mystical Church:

Despite the Church’s historical ambivalence towards mysticism, there is a growing recognition among many Christian thinkers and leaders that the Church needs to become more open to the mystical dimensions of faith in order to remain relevant and transformative in the modern world.

In an age of increasing secularization and individualism, many people are seeking a more direct and personal experience of the sacred that goes beyond the confines of traditional religious doctrines and practices. They are looking for a spirituality that speaks to the depths of their being, that connects them with the mystery and beauty of the universe, and that empowers them to live with greater compassion, purpose, and joy.

By embracing the insights and practices of the mystical tradition, the Church can offer a more compelling and transformative vision of the Christian life that meets these deep human needs and aspirations. This may require a greater openness to symbolic and metaphorical interpretations of scripture, a more inclusive and participatory model of religious community, and a greater emphasis on practices of contemplation, meditation, and inner transformation.

At the same time, the Church must also find ways to balance the mystical and the institutional, the experiential and the doctrinal. It must maintain its commitment to the core teachings and values of the Christian tradition, while also creating space for the diversity of spiritual paths and experiences that exist within the community of faith.

This is a challenging task, but it is one that is essential for the future of Christianity in a rapidly changing world. By learning from the example of mystics like Meister Eckhart and Carl Jung, and by cultivating a more contemplative and integral approach to spirituality, the Church can help to lead the way towards a more authentic, inclusive, and transformative vision of the Christian life.

The Ego’s Resistance to the Unconscious:

Just as the Church has often resisted and suppressed the mystical dimensions of faith, the ego in the individual psyche often resists and suppresses the unconscious dimensions of the self. The ego, which represents the conscious, rational, and individual aspects of the self, seeks to maintain control and stability in the face of the vast, mysterious, and often threatening forces of the unconscious.

The ego fears that surrendering to the unconscious could lead to a loss of identity, a dissolution of boundaries, or a descent into chaos and irrationality. It wants to believe that it is in charge, that it can navigate the challenges of life through willpower, logic, and planning alone.

However, the reality is that the ego is not as autonomous or powerful as it imagines itself to be. It is shaped by forces beyond its control, including the influences of family, culture, and society, as well as the deeper currents of the psyche that flow beneath the surface of conscious awareness.

The unconscious, which contains the repressed, forgotten, and undeveloped aspects of the self, exerts a constant pressure on the ego, seeking expression and integration. When the ego resists this pressure, it can lead to psychological and spiritual imbalances, such as anxiety, depression, addiction, and creative blockages.

The path of wholeness and fulfillment, therefore, requires the ego to learn to surrender its illusions of control and to open itself to the wisdom and guidance of the unconscious. This does not mean abandoning the ego altogether, but rather developing a more flexible and permeable sense of self that can adapt to the changing needs and circumstances of life.

The Wisdom of the Unconscious:

When the ego learns to listen to the unconscious, it can discover a vast source of wisdom, creativity, and spiritual insight. The unconscious contains the archetypes, symbols, and energies that connect us with the deeper dimensions of reality, and that can guide us towards greater wholeness, purpose, and fulfillment.

Mystical experiences, which involve a direct encounter with the divine or the transcendent, often emerge from the depths of the unconscious. They can provide a profound sense of unity, beauty, and meaning that goes beyond the limitations of the rational mind and the individual ego.

By cultivating a relationship of dialogue and partnership with the unconscious, the ego can learn to navigate the challenges of life with greater flexibility, resilience, and creativity. It can draw upon the resources of the psyche to find new solutions to problems, to heal old wounds and traumas, and to discover a deeper sense of purpose and connection.

This path of integration is not always easy or comfortable, as it requires a confrontation with the shadow aspects of the self and a willingness to let go of old patterns and identities. However, it is only by embracing the full complexity and depth of the psyche that we can achieve genuine wholeness, authenticity, and spiritual growth.

Both the Church and the ego seek to maintain control and stability in the face of the vast, mysterious, and often threatening forces of mysticism and the unconscious. The path of genuine transformation requires a willingness to surrender this control and to open oneself to the wisdom and guidance of the deeper dimensions of reality.

This path is not always easy, as it requires a confrontation with the shadow aspects of ourselves and our institutions, and a willingness to let go of old patterns and identities. However, it is only by embracing the full complexity and depth of the human experience that we can achieve genuine wholeness, authenticity, and spiritual growth.

If you enjoyed this article check out the podcast: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

David Tacey discusses the churches attitudes to mysticism in the video below:

Bibliography:

- Eckhart, Meister. (Various editions). Selected Writings.

- Eckhart, Meister. (Various editions). Sermons and Treatises.

Further Reading:

- McGinn, B. (2001). The Mystical Thought of Meister Eckhart: The Man from Whom God Hid Nothing. Crossroad Publishing Company.

- Tobin, F. (1986). Meister Eckhart: Thought and Language. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Davies, O. (1991). Meister Eckhart: Mystical Theologian. SPCK Publishing.

- Fox, M. (2000). Breakthrough: Meister Eckhart’s Creation Spirituality in New Translation. Image Books.

- Jung, C.G. (1958). Psychology and Religion: West and East. Routledge.

- Tacey, D. (2013). The Darkening Spirit: Jung, Spirituality, Religion. Routledge.

- Underhill, E. (1911). Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness. Methuen & Co.

- McGinn, B. (1991). The Foundations of Mysticism: Origins to the Fifth Century. Crossroad Publishing Company.

- Hollywood, A. (1995). The Soul as Virgin Wife: Mechthild of Magdeburg, Marguerite Porete, and Meister Eckhart. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Caputo, J.D. (1978). The Mystical Element in Heidegger’s Thought. Ohio University Press.

- Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Shambhala.

- Harmless, W. (2008). Mystics. Oxford University Press.

- Jantzen, G.M. (1995). Power, Gender and Christian Mysticism. Cambridge University Press.

- Keller, C. (1986). From a Broken Web: Separation, Sexism and Self. Beacon Press.

- Knoll, R. (2022). The Sins of the Fathers: A Study in the Atlantic Slave Traders, 1441-1807. Yale University Press

Mystics and Gurus

0 Comments