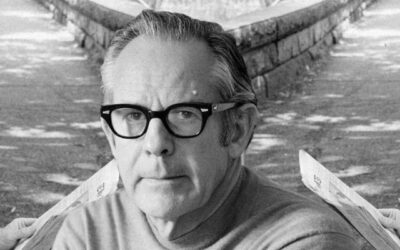

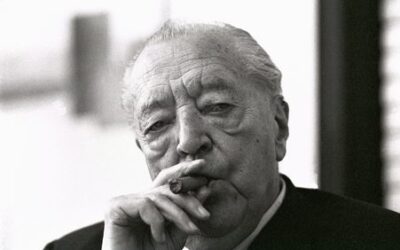

Ronald David Laing (1927-1989) was a pioneering Scottish psychiatrist who challenged the conventional wisdom of his field, offering a provocative existential and social perspective on mental illness. His radical views, unorthodox therapeutic methods, and scathing critique of psychiatric institutions made him a counterculture icon of the 1960s and 70s, while also attracting controversy and opposition from the mainstream medical establishment.

The Divided Self

In his groundbreaking first book, The Divided Self (1960), Laing argued that schizophrenia should be understood not as a medical disease but as a rational strategy that a person invents to live in an unlivable situation. Drawing on existential philosophy and phenomenology, he proposed that the “schizophrenic” is suffering from “ontological insecurity”—a fragmentation of the self and a loss of a stable sense of being-in-the-world.

Laing contended that the bizarre beliefs and behaviors associated with schizophrenia are actually meaningful attempts to cope with the anxiety and emptiness of a false, compliant self divorced from genuine feeling and spontaneity. In his view, the “psychotic” voyage could be a transformative journey of self-discovery, a tortuous path toward authenticity and healing.

The Politics of Experience

Laing’s 1967 work The Politics of Experience expanded his existential analysis to encompass the social and political dimensions of mental illness. He argued that madness is not a medical condition to be cured but a label we attach to experiences and expressions that a particular culture finds unacceptable or incomprehensible. “Insanity,” he declared, “is a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world.”

In this light, Laing saw psychiatry as an oppressive instrument of social control, a way of forcing conformity and invalidating the individual’s lived experience. The psychiatric establishment, he charged, was more concerned with adjusting the individual to a mad society than with addressing the alienating conditions that drive people to madness. “Schizophrenia,” he quipped, “cannot be understood without understanding despair.”

Therapeutic Experiments

Moving beyond theory, Laing sought to create alternative therapeutic spaces that could foster genuine healing and self-realization. In 1965, he co-founded the infamous Kingsley Hall in London, a medication-free community where patients and therapists lived together as equals. Influenced by the budding human potential movement, Laing envisioned the project as a kind of asylum—a safe haven where “schizophrenics” could fully immerse themselves in their inner journeys, however turbulent.

While Kingsley Hall eventually devolved into chaos, it embodied Laing’s belief in the necessity of “going through madness” to arrive at a more authentic, spiritually grounded self. In place of the suppressive “treatments” of conventional psychiatry—drugs, electroshock, lobotomy—he advocated for a radically humanistic approach based on empathy, respect, and guidance. The therapist, in his view, should serve as an “enlightened witness” to the patient’s process rather than an agent of control and conformity.

Legacy and Critique

Laing’s ideas had a profound impact on the anti-psychiatry movement and the cultural zeitgeist of his era. His existential perspective challenged the medical model’s reduction of human suffering to brain chemistry, emphasizing instead the lived context of distress. By attending to the interpersonal and societal dimensions of madness, he helped to humanize the patient and expose the institutional abuses of psychiatry.

At the same time, Laing was a controversial and polarizing figure, and many of his ideas have been met with skepticism or outright rejection by the psychiatric establishment. Critics have accused him of romanticizing mental illness, blaming families for schizophrenia, and neglecting the biological factors in serious psychological disorders. Some contend that his approach denied patients the expert help they needed and exposed them to dangerous experimentation.

Moreover, while Laing was prescient in recognizing the link between emotional disturbance and societal conditions, his analysis at times lapsed into a crude social determinism that downplayed individual agency and resilience. His utopian faith in the transformative potential of madness also underestimated the devastation wrought by chronic psychosis on individuals and families.

Conclusion

Despite these criticisms, R.D. Laing’s work remains an enduring testament to the necessity of a more humane, holistic psychiatry. In a field still dominated by biological reductionism and the “broken brain” model of mental illness, his existential perspective serves as a crucial counterbalance—a reminder of the meaning-seeking person behind the diagnostic label.

While few contemporary theorists would fully endorse Laing’s more extreme views, his core insights continue to resonate. He taught us to listen carefully to the “mad,” to respect the subjective experience of the sufferer, and to recognize the impact of societal conditions on personal well-being. As we grapple with epidemic rates of depression, anxiety, and addiction in our own time, his prophetic critique of modernity’s “malignant normality” seems more relevant than ever.

Ultimately, Laing’s legacy lies in his radical empathy—his willingness to take seriously the inner world of the disturbed and to question the conventional boundaries between madness and sanity. He dared us to embrace the full spectrum of human experience, however frightening or extreme. In doing so, he enlarged our conception of the psyche and called us to a more authentic way of being with ourselves and each other. As we navigate the challenges of an ever more uncertain world, that message is one we urgently need to hear.

Further Resources:

- Collier, A. (1977). R.D. Laing: The Philosophy and Politics of Psychotherapy. Pantheon.

- Kotowicz, Z. (1997). R.D. Laing and the Paths of Anti-Psychiatry. Routledge.

- Laing, R.D. (1960). The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. Penguin.

- Laing, R.D. (1967). The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise. Penguin.

- Laing, R.D. (1969). Self and Others. Pantheon.

- Laing, R.D. & Esterson, A. (1964). Sanity, Madness, and the Family. Penguin.

- Miller, G. (2008). R.D. Laing. Edinburgh University Press.

0 Comments