Who was Albert Ellis?

Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) is a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy that focuses on identifying and challenging irrational beliefs in order to improve emotional well-being and behavioral outcomes. Developed by psychologist Albert Ellis in the 1950s, REBT has become one of the most influential and widely practiced models of psychotherapy. This article will explore the origins and core assumptions of REBT, its key techniques and interventions, evidence base, and place in the broader landscape of psychotherapy.

Origins and Development of REBT

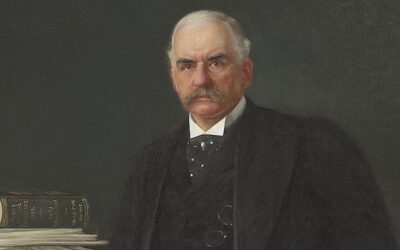

Albert Ellis: Biography and Influences

REBT was founded by Albert Ellis (1913-2007), an American psychologist and psychotherapist. Born in Pittsburgh and raised in New York City, Ellis was the eldest of three children in a Jewish family. He described his father as emotionally distant and his mother as self-absorbed, leading to a tumultuous home life.

As a young man, Ellis struggled with severe social anxiety and depression. He experimented with various self-help techniques, including reading philosophy and psychology books, to overcome his fears and low self-esteem. After earning a business degree from the City University of New York, Ellis began a career in business but found it unfulfilling.

In the 1940s, Ellis returned to school, earning a PhD in clinical psychology from Columbia University. He initially trained and practiced as a psychoanalyst under the influence of Sigmund Freud, Karen Horney, and other prominent figures. However, he became increasingly dissatisfied with the lengthy, indirect, and past-focused nature of psychoanalysis.

Ellis was heavily influenced by ancient Stoic philosophy, particularly the writings of Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. The Stoics emphasized that humans are disturbed not by events themselves but by their judgments and interpretations about those events. They taught that we can achieve peace of mind by accepting what is not in our control and focusing on our chosen responses.

Other key influences on Ellis included:

- Alfred Korzybski and general semantics, which highlighted the powerful role of language in shaping perception and experience

- Behaviorism and learning theory, which demonstrated how thoughts and emotions could be conditioned and modified

- Existentialism, particularly the idea of taking responsibility for one’s own life choices and meaning-making

- Erich Fromm’s concept of rational faith and the courage to be oneself

In the early 1950s, Ellis began developing and practicing his own approach, originally called Rational Therapy. His 1955 article “New Approaches to Psychotherapy Techniques” and 1957 book How to Live with a Neurotic were seminal publications that laid out the foundations of his model. In 1959, Ellis founded the Institute for Rational Living (now called the Albert Ellis Institute) in New York City to advance research, training, and practice in what became known as Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy.

Cultural Issues:

The post-World War II era in America, when Ellis developed REBT, was a time of significant cultural and economic change. Several key forces influenced the emergence and reception of his ideas:

Faith in science and reason:

After the war, there was a growing cultural emphasis on the power of science, technology, and rational thinking to improve human life. This zeitgeist was receptive to a therapy model grounded in logic and empiricism.

Emphasis on efficiency and functionality:

In many domains of life, from business to education to mental health, there was a push for streamlined, results-oriented approaches. REBT’s focus on pragmatic, present-centered change aligned with this ethos.

Individualism and self-improvement:

The 1950s saw a rise in self-help literature and a cultural focus on personal growth and fulfillment. REBT’s message of self-responsibility and the ability to change one’s thinking fit well with this mindset.

Critique of psychoanalysis:

While still culturally dominant, psychoanalysis was increasingly questioned for its lengthy timeline, emphasis on the unconscious and past events, and lack of scientific rigor. REBT offered a more direct, active, and evidence-based alternative.

Rise of cognitive psychology:

The 1950s and 60s saw the emergence of cognitive psychology, which studied internal mental processes such as attention, memory, and decision-making. REBT was part of this larger “cognitive revolution” in understanding human behavior.

Demand for time-limited, cost-effective treatments:

With the growth of managed care and employee assistance programs, there was increasing pressure for demonstrably efficient and economical therapy models. REBT fit this need with its briefer duration and focus on measurable outcomes.

Existential and humanistic influences:

Existentialism, with its emphasis on personal responsibility and authenticity, and humanistic psychology, with its focus on human potential and growth, were gaining cultural currency. REBT incorporated elements of both, even as it critiqued some of their assumptions.

These cultural and economic forces created both opportunities and challenges for the spread of REBT. On one hand, there was a receptiveness to a practical, science-based approach that empowered individuals to change their thoughts and behaviors. On the other hand, REBT faced resistance from the psychoanalytic establishment and those who saw it as superficial or insufficiently concerned with emotion and the unconscious.

Ellis was a tireless advocate for REBT and a prolific writer and speaker. He engaged in public debates and media appearances to promote his ideas and challenge the dominance of Freudian theory. At the same time, he built alliances with like-minded cognitive and behavioral therapists such as Aaron Beck and Donald Meichenbaum.

As the cultural landscape shifted in the 1960s and 70s, with increased emphasis on social justice, systemic change, and alternative states of consciousness, REBT’s focus on the individual and rational control faced new criticisms. Some saw it as overly conformist, culturally biased, or neglectful of deeper emotional and spiritual needs.

Ellis continued to refine and defend REBT throughout his long career, engaging with critiques and integrating new developments in cognitive science, behavior therapy, and emotion theory. By the time of his death in 2007, REBT was firmly established as a major school of psychotherapy, with international institutes, journals, and thousands of trained practitioners.

Core Assumptions and Tenets of REBT

The REBT model is built on several key assumptions about the nature of human cognition, emotion, and behavior:

- Cognitions, emotions, and behaviors are interrelated and mutually influencing. The way we interpret events (cognitions) affects how we feel (emotions) and act (behaviors). In turn, our feelings and actions reinforce our interpretations.

- Humans have innate tendencies toward both rational and irrational thinking. We are capable of reason and realistic appraisals, but we also have strong pulls toward rigid, globalized, and dysfunctional beliefs.

- Irrational beliefs are the primary source of psychological disturbance. When we interpret adversities through a lens of musts, awfulizing, low frustration tolerance, and negative self-rating, we create unnecessary emotional distress for ourselves.

- We can learn to recognize and dispute irrational beliefs. Through self-awareness, logical analysis, and practice, we can catch ourselves engaging in irrational thought patterns and actively challenge them.

- Rational beliefs lead to appropriate emotions and adaptive behaviors. By replacing dogmatic “musts” with preferences, acknowledging that setbacks are difficult but not awful, and accepting ourselves as fallible beings, we experience sadness rather than depression, concern rather than anxiety, and regret rather than shame.

The REBT model is often summed up in the ABC framework:

- A = Activating event (the situation or trigger)

- B = Beliefs (our interpretations and assumptions about the event)

- C = Consequences (the emotional and behavioral results of our beliefs)

The goal of REBT is to D = Dispute irrational beliefs and develop E = Effective new beliefs and F = Feelings/behaviors.

REBT’s View of the Unconscious

Unlike psychoanalysis, REBT does not posit a powerful unconscious mind filled with repressed conflicts and desires. Ellis acknowledged that we are not always aware of our beliefs and self-talk, but maintained that irrational ideas can be made conscious and changed through introspection and practice.

For Ellis, the “unconscious” consisted mainly of habitual thought patterns that were learned early in life and operate automatically. By tuning into one’s “internalized sentences” and evaluating them rationally, a person can shift even long-standing irrational beliefs.

REBT does recognize that early childhood experiences and relationships shape our belief systems, and that some core irrational ideas may be rooted in traumas or unmet needs from this formative period. However, it emphasizes that we perpetuate our own disturbances in the present by re-indoctrinating ourselves with dysfunctional self-talk. The goal is not to uncover hidden causes, but to take responsibility for changing our cognitive habits here and now.

REBT’s View of the Self

REBT promotes an unconditional self-acceptance that distinguishes between a person’s essence and their behaviors. Ellis argued against global self-rating, whether positive or negative. A person is never rotten or worthless, no matter how many bad acts they commit; nor are they special or superior for performing well.

Instead, REBT encourages people to rate only their traits and actions along a continuum, while accepting themselves as complex, imperfect human beings who are striving to do better. Unconditional self-acceptance means acknowledging one’s flaws and failings without shame or self-downing.

This view of the self contrasts with the psychoanalytic emphasis on unconscious conflicts between instinctual drives and social demands. It also differs from the humanistic ideal of a growth-oriented, inherently positive self. For REBT, the self is not a fixed entity to be actualized, but an ongoing process of rational self-creation.

The Primacy of Thinking in REBT

More than any other cognitive-behavioral therapy, REBT places the primary emphasis on thoughts as the mediators between events and emotions. While acknowledging the influences of biology, environment, and behavior, Ellis argued that beliefs are the most direct and powerful determinants of how we feel.

This focus on thinking sets REBT apart from behavioral models that see cognition as just one type of behavior to be conditioned, as well as from experiential therapies that prioritize emotions and sensations over language and logic. For REBT, it is our evaluative judgments and interpretations that lead to emotional consequences.

At the same time, REBT recognizes that thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are complexly interlinked and mutually reinforcing. Irrational beliefs both arise from and contribute to maladaptive emotions and actions. The goal is not to eliminate emotions, but to change self-defeating thoughts so that feelings are appropriate to the situation.

REBT Interventions and Techniques

REBT employs a wide range of cognitive, emotive, and behavioral interventions to help clients identify and modify their irrational beliefs. Key techniques include:

Cognitive Techniques

- Logical disputation: Systematically challenging the rationality and coherence of dysfunctional beliefs using deductive reasoning. This often involves examining the evidence for and against a belief, showing how it leads to inconsistency or absurdity when taken to its logical extreme.

- Empirical disputation: Questioning the factual basis for an irrational belief and testing its validity against observable reality. This may involve looking at past experiences that contradict the belief, or conducting behavioral experiments to gather new data.

- Pragmatic disputation: Evaluating the practical consequences of holding a belief, and showing how it leads to self-defeating emotions and behaviors. The goal is to demonstrate that the belief is not helpful or healthy, even if it seems true.

- Rational self-statements: Developing and rehearsing adaptive self-talk to counter irrational thoughts in triggering situations. For example, replacing “I must always be perfect” with “I prefer to do well, but I can accept myself as a worthy person even when I make mistakes.”

- Reframing and reorienting: Looking at situations from different angles to gain perspective and reduce catastrophic thinking. This could mean considering the long-term impact of a setback, remembering past times one has coped with similar difficulties, or refocusing on positive goals and values.

Emotive Techniques

- Rational-emotive imagery: Vividly imagining oneself coping adaptively with feared situations while practicing rational self-talk. This helps clients generate the emotional responses they would like to have to challenging events.

- Shame-attacking exercises: Deliberately engaging in harmless behaviors that one is afraid will lead to humiliation or rejection, in order to desensitize oneself to the fear of negative social judgment. For example, singing out loud in a public place or wearing mismatched socks to work.

- Role-playing and reverse role-playing: Acting out relevant scenarios and switching roles with the therapist to gain new perspectives and practice new behaviors. This could involve reenacting a difficult conversation or argument, with the client playing both themselves and the other person.

- Humor and irreverence: Using exaggeration, irony, or gentle mockery to highlight the absurdity of irrational beliefs and create emotional distance from them. Ellis was known for his colorful and confrontational style, which he used to jolt clients out of dysfunctional thinking patterns.

Behavioral Techniques

- Exposure: Gradually and repeatedly confronting feared situations, either in real life or imagination, to reduce anxiety and build confidence. This could involve taking progressively more challenging social risks, touching contaminated objects, or revisiting trauma-related memories.

- Behavioral activation: Engaging in enjoyable and meaningful activities, even when one doesn’t initially feel like it, to improve mood and counter depressive avoidance. This could mean scheduling regular exercise, social outings, or creative hobbies.

- Skill training: Learning and practicing effective communication, problem-solving, and self-management techniques. This could include assertiveness training, stress inoculation, or study skills. The goal is to build actual competencies that support rational beliefs.

REBT therapists flexibly combine these and other techniques based on the client’s specific problems and preferences. Interventions are active, directive, and often assigned as homework between sessions to foster self-reliance and real-world application.

Goals and Stages of Treatment

The ultimate goal of REBT is to help clients develop a rational philosophy of life that promotes emotional well-being and adaptive functioning. Specific goals include:

- Identifying and understanding one’s irrational beliefs and how they lead to emotional disturbance

- Developing the ability to catch and dispute irrational thoughts in the moment they occur

- Replacing absolute, rigid demands with flexible, context-appropriate preferences

- Cultivating unconditional self-acceptance and tolerance for frustration and discomfort

- Engaging in fulfilling work, relationships, and leisure activities while pursuing meaningful goals

- Becoming one’s own therapist by internalizing rational self-talk and problem-solving skills

Treatment typically proceeds through the following stages:

- Assessment and rapport-building: The therapist gathers information about the client’s presenting problems, relevant history, and goals for therapy. The therapist works to establish a collaborative, trusting relationship and explain the REBT approach.

- Insight and awareness: The client learns to recognize their irrational beliefs and how they contribute to their disturbed emotions and behaviors. The ABC model is introduced and applied to specific situations from the client’s life.

- Disputation and cognitive change: The client and therapist actively challenge the client’s irrational beliefs using a variety of disputation techniques. The client practices generating rational alternatives and strengthening them with evidence and logic.

- Emotional and behavioral change: The client engages in emotive and behavioral exercises, in session and as homework, to translate intellectual insights into actual changes in feeling and action. This may include exposure, role-playing, imagery, and other experiential techniques.

- Generalization and maintenance: As the client demonstrates progress, the focus shifts to applying rational thinking skills to new situations and anticipating future challenges. The client develops self-therapy plans to continue practicing and reinforcing their learning after formal treatment ends.

The length of REBT varies depending on the complexity and severity of the client’s issues, but is typically briefer than traditional psychoanalysis. Many clients experience significant improvement within 10-20 sessions, although some may need more extended work.

Evidence Base and Efficacy

REBT is an empirically supported treatment with a substantial body of research evidence. Dozens of randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have found REBT and other cognitive-behavioral therapies to be effective for a wide range of psychological problems, including:

- Depression and mood disorders

- Anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety, panic disorder, phobias)

- Trauma and stress-related conditions (e.g., PTSD, adjustment disorders)

- Anger and aggression problems

- Substance use and addictive behaviors

- Eating disorders and body image issues

- Personality disorders

- Chronic pain and health-related concerns

- Relationship and family conflicts

- Child and adolescent behavioral and emotional problems

Research has consistently found that REBT leads to significant reductions in symptoms, irrational beliefs, and negative emotions, as well as improvements in self-esteem, coping skills, and overall life satisfaction. Effect sizes are typically large, and gains are often maintained at follow-up assessments months or years after treatment.

REBT’s efficacy appears to be largely due to its focus on actively modifying irrational beliefs and teaching generalizable skills. Studies have shown that changes in irrational thinking precede and predict later improvements in emotional and behavioral symptoms. REBT’s effects are mediated by acquisition of rational coping strategies and increased self-efficacy.

Compared to other therapies, REBT has been found to be as effective as cognitive therapy and behavior therapy, and more effective than psychodynamic or nondirective supportive therapies in treating depression and anxiety. Some studies suggest REBT may achieve results more quickly due to its efficient focus on core irrational beliefs.

REBT also has good scientific support as a self-help approach. Many studies have found that REBT-based bibliotherapy (using self-help books), computerized programs, and online courses can significantly reduce distress and irrational thinking. These minimal-contact methods make REBT principles and techniques more widely accessible.

At the same time, REBT has not been extensively researched for all problems and populations. More studies are needed on its efficacy for severe mental illness, children and adolescents, and diverse cultural groups. The active-directive style of REBT may not suit all clients, and the model has been criticized for downplaying emotions, overemphasizing rationality, and being insufficiently attuned to interpersonal dynamics.

Clinical Applications and Contexts

REBT has been successfully applied in a variety of clinical settings and populations, including:

Individual, group, and couples therapy

Brief therapy in primary care, employee assistance, and managed care settings

School and educational counseling for academic underachievement, test anxiety, and behavioral problems

Coaching and skill training in business, sports, and the military

Preventive mental health and stress management programs for at-risk groups

Addiction and rehabilitation counseling

Parenting and family education programs

Self-help and personal development workshops and retreats

The structured, skill-building nature of REBT makes it well-suited for time-limited, problem-focused interventions. It can be flexibly adapted for different age groups, ability levels, and cultural contexts by modifying the language and examples used.

REBT has been increasingly integrated with other evidence-based therapies, such as acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and schema therapy. These integrative approaches combine REBT’s focus on rational disputation with newer strategies for promoting acceptance, emotion regulation, and value-congruent living.

REBT principles have also been applied to non-clinical domains such as education, business, politics, and philosophy. Ellis promoted the idea of rational living skills as a core subject to be taught in schools and universities to foster psychological resilience and critical thinking. REBT’s emphasis on pragmatic, flexible, and reality-based thinking has resonated in the business world, particularly in the areas of leadership, decision-making, and sales.

Distinctive Features of REBT

While REBT shares common ground with other cognitive-behavioral therapies, several features distinguish it as a unique approach:

Philosophical emphasis:

REBT is not just a set of techniques, but a comprehensive theory of human nature and well-being grounded in stoic and humanistic philosophy. It promotes rational living as an overarching way of life, not just a treatment for specific disorders.

Focus on irrational beliefs:

More than any other therapy, REBT places the primary emphasis on identifying and challenging absolutistic, illogical, and dysfunctional beliefs as the core of psychological disturbance. Other cognitive therapies focus more on automatic thoughts, information processing biases, or maladaptive schemas.

Elegant simplicity:

REBT offers a parsimonious conceptual framework (the ABC model) and a streamlined set of intervention principles that can be easily understood and applied by clients. It avoids jargon and aims to teach clear, common-sense methods for solving problems.

Vigorous disputation:

REBT employs active, confrontational, and at times combative techniques to directly challenge irrational thinking. Therapists are encouraged to be persistent and even forceful in arguing against the client’s self-defeating beliefs, using logical persuasion and a touch of irreverent humor.

Secondary disturbance focus:

REBT attends not only to the emotional distress caused by external events, but also to the distress people create about their distress – such as feeling ashamed about one’s depression or anxious about one’s panic attacks. Addressing these meta-emotional problems is a key target in REBT.

Unconditional acceptance:

REBT teaches people to fully accept themselves, others, and life, even while working to change what they can. It promotes an attitude of unconditional regard and respect for all humans as fallible, imperfect beings, rather than rating people as good or bad based on their actions.

Multimodal interventions: While prioritizing cognition, REBT also employs emotive and behavioral methods to foster change. It encourages clients to work in practical, experiential ways to translate intellectual insights into emotional and behavioral realities.

Legacy of R.E.B.T.

Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, developed by Albert Ellis in the 1950s, is a trailblazing approach that has left an indelible mark on the field of psychotherapy. By illuminating the critical role of cognition in shaping emotional experience and behavioral responses, REBT paved the way for the cognitive revolution in psychology and the emergence of evidence-based, present-focused therapies.

REBT’s enduring appeal lies in its elegant simplicity, philosophical depth, and pragmatic focus on teaching people tangible skills for overcoming self-defeating patterns of thought and action. Its core principles – that our beliefs powerfully influence our feelings and behaviors, that we can learn to rationally evaluate and change our irrational beliefs, and that unconditionally accepting ourselves and others is essential to well-being – have stood the test of time and been validated by a substantial body of empirical research.

At the same time, REBT continues to evolve in response to new scientific findings, cultural developments, and critiques. Contemporary REBT has incorporated elements from a range of therapies, from mindfulness to schema-focused approaches, while maintaining its signature emphasis on active, rational disputation. It has been successfully adapted for diverse clinical settings and populations, from school counseling to addiction treatment to executive coaching.

As the field of psychotherapy moves toward increasing integration and personalization, REBT’s legacy as a foundational, transdiagnostic approach will endure. Its core insights about the interplay of cognition, emotion, and behavior, the ubiquity of irrational thinking, and the power of rational self-analysis and problem-solving are now woven into the fabric of virtually all empirically supported therapies.

Perhaps Ellis’s most vital contribution was his unwavering faith in the human capacity for rational thinking and self-directed change. REBT’s optimistic message is that we can all learn to recognize and relinquish our irrational beliefs, face life’s adversities with resilience and grace, and create our own meaning and fulfillment. In an era of rapid technological and social change, this vision of thoughtful, responsible, and rational living is more needed than ever.

Timeline

1913: Albert Ellis is born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

1934: Ellis earns a business degree from the City University of New York.

1942: Ellis earns a PhD in clinical psychology from Columbia University.

1943-1947: Ellis practices psychoanalysis, becoming increasingly dissatisfied with its inefficiency.

1955: Ellis presents “Rational Therapy: A New Approach to Psychotherapy” at the American Psychological Association convention, marking the public debut of his approach.

1957: Ellis publishes “How to Live with a Neurotic,” his first book on rational therapy.

1959: Ellis founds the Institute for Rational Living in New York City.

1962: Ellis’s book “Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy” is published, elaborating the theoretical and practical foundations of Rational Therapy.

1960s: Ellis’s approach gains popularity and begins to be known as Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET). Ellis debates psychoanalysts and behaviorists and demonstrates RET’s techniques in workshops and public presentations.

1975: Maxie Maultsby publishes “Help Yourself to Happiness through Rational Self-Counseling,” introducing a self-help version of RET.

1970s-1980s: Controlled outcome studies are conducted on RET, establishing its efficacy for a range of psychological problems. RET is increasingly integrated with behavior therapy techniques.

1993: The Institute for Rational-Emotive Therapy is renamed the Albert Ellis Institute. The first World Congress on Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy is held.

1994: RET is officially renamed Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) to reflect its multimodal emphasis.

1990s-2000s: REBT is applied to new clinical populations and problems, including personality disorders, anger management, and addiction. Integrations with other cognitive-behavioral therapies are developed.

2007: Albert Ellis dies at the age of 93. The Albert Ellis Institute continues his legacy, offering training and treatment in REBT.

2000s-present: REBT research and practice continues worldwide. Newer applications include coaching, organizational consulting, and online therapy. REBT principles are integrated into “third wave” cognitive-behavioral approaches.

Bibliography

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

David, D., Lynn, S.J. & Ellis, A. (2010). Rational and irrational beliefs: Research, theory, and clinical practice. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Dobson, K. S. (Ed.). (2009). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Dryden, W. (2012). The “ABCs” of REBT I: A preliminary study of errors and confusions in counselling and psychotherapy textbooks. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 30(3), 133-172.

Dryden, W., & David, D. (2008). Rational emotive behavior therapy: Current status. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 22(3), 195-209.

Ellis, A. (1957). Rational psychotherapy and individual psychology. Journal of Individual Psychology, 13(1), 38-44.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart.

Ellis, A. (2001). Overcoming destructive beliefs, feelings, and behaviors: New directions for rational emotive behavior therapy. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Ellis, A. (2003). Early theories and practices of rational emotive behavior theory and how they have been augmented and revised during the last three decades. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 21(3/4), 219-243.

Ellis, A., & Dryden, W. (2007). The practice of rational emotive behavior therapy (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Publishing Co.

Ellis, A., & Harper, R. A. (1975). A new guide to rational living. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ellis, A., & MacLaren, C. (2005). Rational emotive behavior therapy: A therapist’s guide (2nd ed.). Atascadero, CA: Impact Publishers.

Engles, G. I., Garnefski, N., & Diekstra, F. W. (1993). Efficacy of rational-emotive therapy: A quantitative analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 1083-1090.

Epictetus (1948). The enchiridion. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. (Original work published about 135 A.D.)

Haaga, D. A. F., & Davison, G. C. (1993). An appraisal of rational-emotive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 215-220.

Hyland, P., & Boduszek, D. (2012). A unitary or binary model of emotions: A discussion on a fundamental difference between cognitive therapy and rational emotive behaviour therapy. Journal of Humanistics and Social Sciences, 1(1), 49-61.

Lyons, L. C., & Woods, P. J. (1991). The efficacy of rational-emotive therapy: A quantitative review of the outcome research. Clinical Psychology Review, 11(4), 357-369.

Maultsby, M. C. (1975). Help yourself to happiness through rational self-counseling. New York: Institute for Rational Living.

Padesky, C. A., & Beck, A. T. (2003). Science and philosophy: comparison of cognitive therapy and rational emotive behavior therapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 17(3), 211-221.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2014). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (8th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Robertson, D. (2010). The philosophy of cognitive-behavioural therapy: Stoicism as rational and cognitive psychotherapy. London: Karnac Books.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Walen, S.R., DiGiuseppe, R., & Dryden, W. (1992). A practitioner’s guide to rational-emotive therapy (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Weinrach, S. G. (1996). Albert Ellis: A personal retrospective. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(4), 409-411.

Weinrach, S. G., Ellis, A., DiGiuseppe, R., Bernard, M. E., Dryden, W., Kassinove, H., Morris, G. B., & Vernon, A. (2006). Rational emotive behavior therapy after Ellis: Predictions for the future. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 24(4), 199-215.

Ziegler, D. J. (2002). Freud, Rogers, and Ellis: A comparative theoretical analysis. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 20(2), 75-91.

0 Comments