What is Self-System Therapy?

Self-System Therapy (SST) is a relatively new form of psychotherapy developed by clinical psychologist Richard Schwartz in the 1980s. The model conceptualizes the mind as being composed of various “parts” or subpersonalities, each with its own unique perspective, interests, memories, and viewpoint. SST proposes that every individual has a “Self” which is the core essence of who you are. The goal of therapy is to access this Self and heal the wounded parts, restoring inner harmony and balance.

SST emerged from Schwartz’s work with eating disorders and family therapy. He noticed that clients would often talk about their eating disorder as if it was a distinct part of themselves and found that directly addressing these parts in therapy led to positive breakthroughs. This experience inspired him to develop a comprehensive model of the mind and a therapeutic approach based on systems thinking.

What are the Core Tenets and Assumptions of Self-System Therapy?

Some of the key principles of SST include:

- The mind is naturally multiple and composed of an interconnected system of “parts” or subpersonalities.

- Everyone has a “Self” which is the core essence of who you are. The Self embodies qualities like curiosity, compassion, confidence, courage, creativity, and connectedness.

- Parts take on extreme roles and stances as a result of trauma or attachment injuries. For example, a part may take on the role of a harsh inner critic in an attempt to protect the system from further harm.

- The goal of therapy is not to eliminate parts but to help them find positive, healthy roles so the entire system can work harmoniously together. This occurs by accessing the Self and allowing it to lead the healing process.

- Lasting healing involves unburdening the pain, shame, and beliefs the parts took on from trauma. When parts are unburdened, their natural strengths and talents can be restored to the system.

- The therapist’s role is to be a compassionate witness and facilitate the client’s internal work rather than be an expert problem-solver. The client’s Self is in charge of the therapy.

Is Self-System Therapy Evidence-Based?

While more rigorous research is needed, a growing number of studies provide preliminary support for the effectiveness of SST for a variety of mental health concerns including:

- Depression and anxiety (Schwartz et al., 2018; Hsieh et al., 2019)

- PTSD (Merscham, 2010; Lucero et al., 2018)

- Substance abuse (Perlinski, 2011)

- Eating disorders (Schwartz, 2001; Giddens, 2012)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (Shadick et al., 2013)

One reason SST hasn’t been studied as extensively as some other therapy models is that it is a highly experiential, process-oriented therapy that can be challenging to manualize and translate into a replicable research protocol. However, interest in researching SST and related “parts work” therapies is rapidly growing.

What Therapeutic Models is Self-System Therapy Similar To?

SST shares some common elements with other therapy models including:

- Psychosynthesis: Developed by Roberto Assagioli, psychosynthesis also uses the language of subpersonalities. It proposes people have a higher Self and the goal is to cultivate a relationship between the Self and subpersonalities.

- Jungian therapy: Jung wrote extensively about complexes, or parts of the unconscious mind that have separated from the ego due to trauma. SST echoes Jung’s view of an inherent drive towards wholeness and integration.

- Gestalt therapy: Gestalt experiments like the “empty chair” technique have similarities to how SST directly engages parts in dialogue.

- ACT and DBT: While the conceptual model is quite different, SST shares an emphasis on mindfulness, acceptance, and self-compassion with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Dialectical Behavior Therapy.

- EMDR: Both SST and EMDR therapy aim to process unresolved traumatic memories in an experiential way.

However, SST is distinct in its focus on fostering Self-to-part relationships and using the Self as the primary healing agent in therapy.

What Were the Cultural and Economic Forces That Influenced the Development of Self-System Therapy?

SST emerged in the 1980s during a time of significant paradigm shifts in psychology. The “cognitive revolution” of the 1960s and 70s was starting to give way to a renewed interest in emotions, subjective experience, and the unconscious mind. At the same time, family systems theory was transforming the practice of psychotherapy.

Psychologists were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the limitations of behaviorism and the medical model. There was a hunger for models that could address the depth and complexity of the human psyche in a more holistic way. The success of books like M. Scott Peck’s “The Road Less Traveled” reflected a public eager for a spiritual dimension to mental health.

Economic changes were also shaping the landscape of psychotherapy. The rise of managed care meant increasing pressure for short-term, “evidence-based” treatments. This created challenges for insight-oriented, experiential therapies like SST.

Backlash against the excesses of the “repressed memory” movement and multiple personality disorder led to greater skepticism towards models emphasizing dissociation or multiplicity. SST had to clearly distinguish itself from these more extreme approaches.

Who Developed Self-System Therapy and What is Their Background?

Dr. Richard Schwartz is the founder of SST. He earned his Ph.D. in marriage and family therapy from Purdue University. After several years practicing family therapy, Schwartz began treatment with a number of eating disorder clients who were unresponsive to traditional therapies. He discovered that as they talked about their eating disorder in a way that personified it, spontaneous healing occurred.

At the time, talking about the psyche as made up of parts was quite radical. Schwartz persisted in developing his model despite some professional skepticism and resistance. He founded The Center for Self Leadership in 1984 to offer training programs for clinicians interested in SST. He was a co-founder of the Internal Family Systems Association in 1998.

Some of Schwartz’s key early influences and collaborators included:

- Michael White and David Epston – pioneers of narrative therapy which emphasizes “externalizing” problems

- David Grove – originator of Clean Language, a technique for minimally-directive questioning

- Virginia Satir – influential family therapist who utilized parts in her practice

- Milton Erickson – master hypnotherapist known for his creative, indirect techniques

Schwartz was also inspired by systems theory, particularly the work of biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy and anthropologist Gregory Bateson. He drew upon their ideas of wholeness, feedback loops, and circular causality to understand the mind as a system of parts.

What is a Timeline of Key Events in the History of Self-System Therapy?

- 1982 – Richard Schwartz begins developing SST model through his work with bulimic clients

- 1984 – The Center for Self Leadership is founded to train therapists in SST

- 1987 – First research study on SST published in Family Process journal

- 1990s – SST spreads rapidly through the psychotherapy field via trainings and conferences

- 1995 – Schwartz publishes “Internal Family Systems Therapy”, the first book on SST

- 1998 – Internal Family Systems Association founded

- 2000s – Increasing research interest in SST, dozens of studies and dissertations completed

- 2013 – SST listed in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices

- 2019 – Schwartz publishes “No Bad Parts”, a book introducing SST to a general audience

Today SST is practiced by thousands of clinicians worldwide. It has been successfully adapted to diverse clinical populations and settings from inpatient to coaching.

How Does Self-System Therapy Conceptualize the Self and Identity?

SST proposes that the Self is the “seat of consciousness” – the “I” from which we observe and experience. The Self is who we are at our core, though we often lose sight of it amongst the noise of our parts.

Qualities of the Self include:

- Curiosity and a desire to learn

- Compassion for self and others

- Calm, grounded confidence

- Courage to face difficult situations

- Creativity and openness to possibilities

- Clarity of thought and perspective

- Deep connection to others and the world

Everyone has a Self, no matter how lost or obscured it may be. SST believes the Self cannot be damaged – it is always whole. But it can be covered up by “exiles”, or wounded parts holding pain and shame. The goal of therapy is to unburden these exiles, thus allowing the Self to more fully shine through.

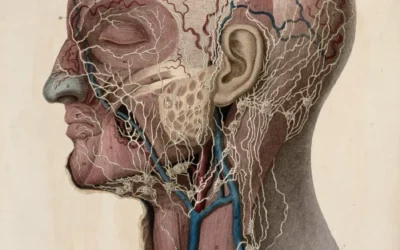

In contrast to the Self, SST conceptualizes the parts as operating more unconsciously from a limited perspective. Parts tend to fall into one of three main categories:

- Managers – parts that try to protect the system by controlling situations and pleasing others

- Firefighters – parts that distract from pain through impulsive or addictive behaviors

- Exiles – parts holding shame, fear, and traumatic memories, often locked away by managers/firefighters

Everyone has their own unique system of parts organized around their particular life experiences. SST emphasizes getting to know your parts with curiosity rather than judging them. Though parts may manifest in destructive ways, they all have good intentions for the overall system.

Unlike some models that see identity as unitary or seek to integrate parts, SST believes multiplicity is natural and even healthy. The goal is not to eliminate or fuse the parts, but to help them work well together in their full diversity with Self in the lead. As Schwartz says, the Self is the conductor and the parts are the players in the orchestra.

What are the Key Interventions and Techniques of Self-System Therapy?

SST utilizes a variety of experiential techniques to help clients access their Self and heal their parts. Some of the key interventions include:

- Insight Dialogue – Talking to clients about their parts and the overall system, providing psychoeducation about the Self-parts framework. Helping clients recognize their common parts and patterns.

- Focusing – Guiding clients to sense into their body and notice the parts that are activated. Teaching clients to be curious about their inner experience without judgment.

- Direct Access – Helping clients get to know a particular part, often through imaginal dialogue. Asking the part questions to discover its role, emotions, body sensations, and beliefs. This process begins to build a trusting relationship between Self and parts.

- Unblending – Assisting clients to “unblend” or separate from a part they may be overly identified with. Techniques like physically moving to a different chair can provide distance from the part’s perspective.

- Appreciating Protectors – Fostering an attitude of gratitude towards manager and firefighter parts. Thanking them for their efforts to protect the system, even if their tactics are ultimately counterproductive.

- Befriending Exiles – Helping clients extend compassion to their exiled, wounded parts. Building trust and connection so the exiles feel safe to share their pain.

- Unburdening – Allowing exiled parts to release the traumatic memories, negative beliefs, and overwhelming emotions they are carrying. This is often done through imagery and ritual, such as visualizing the burdens being burned or buried. New positive beliefs are installed.

- Witnessing – The therapist embodies Self-energy and maintains a stance of compassionate witnessing. They track the client’s process without trying to control or interpret it.

- Mapping the System – Drawing diagrams or “maps” of the key parts and their relationships. Noticing patterns and polarizations between parts.

- Parts Informed Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy – Once parts are differentiated and the Self is strong, using CBT and other skill-building techniques to help parts learn new behaviors and responses.

Rather than a rigid protocol, SST emphasizes the therapist’s creativity and attunement to the unique needs of each client’s system. The ultimate goal is for clients to develop their own Self-leadership so they can continue unburdening and harmonizing their parts outside of therapy.

What Are the Goals and Stages of Treatment in Self-System Therapy?

The broad goals of SST are:

- Differentiate the parts and build connections and trust between them

- Unburden the exiles so they are no longer stuck in trauma or shame

- Develop a strong Self to lead the system in a compassionate, harmonious way

SST conceptualizes treatment as progressing through three main stages:

- Mapping and stabilizing the system

- Introducing the Self-parts framework

- Identifying the client’s key parts and their roles

- Building the Self’s capacity to notice and be curious towards parts

- Developing techniques to unblend from parts when needed

- Appreciating protectors and their efforts to safeguard the system

- Healing the exiles

- Establishing trust and connection between Self and exiles

- Learning the stories and burdens the exiles carry

- Reparenting the exiles from Self

- Allowing the exiles to share their pain and release their burdens

- Inviting the exiles into the present and helping them find new roles

- Integration and Self-leadership

- All parts have access to Self-energy

- System is functioning harmoniously with each part playing a valuable role

- Self is able to lead compassionately amidst life’s challenges

- Client has tools to continue unburdening parts on their own

These stages are not always linear – there is often cycling back and forth as different parts and clusters come forward in therapy. The ultimate goal is not to “finish” the work, but to have a Self-led system that can navigate new situations and challenges resiliently.

In What Contexts is Self-System Therapy Usually Practiced?

SST is a flexible model that has been applied in a variety of clinical contexts including:

- Individual adult psychotherapy

- Couples and family therapy

- Group therapy

- Children and adolescents

- Addictions treatment

- Trauma recovery

- Eating disorder treatment

- Inpatient settings

- Coaching and personal growth workshops

SST seems to be especially helpful for clients with complex trauma, dissociation, or issues rooted in childhood experiences. It provides a compassionate framework for working with “resistance” or “self-sabotage.” SST’s hopeful view of the Self and emphasis on internal attunement can be empowering for clients who feel fragmented or self-critical.

While SST is used as a standalone therapy, it also integrates well with other models. Many therapists incorporate SST techniques into their existing approach. The Self-parts framework can be a clarifying addition to therapies like EMDR, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, CBT, and psychodynamic work.

One limitation of SST is that it requires an openness to working experientially and comfort accessing intuitive ways of knowing. Clients who prefer a highly structured, rational approach may find SST frustrating or pointless. It’s also not recommended for clients who are actively suicidal, violent, or struggling with reality-testing. Some degree of stability and groundedness is needed to dive into parts work.

As with any model, the therapeutic relationship is paramount. Clients need to feel safe and understood by their SST therapist to venture into their inner worlds so vulnerably. Cultural sensitivity and humility are essential, as parts are often shaped by societal and systemic factors. SST therapists must be willing to examine their own parts that get activated in the therapy process.

What is Unique About Self-System Therapy?

Some of the distinctive elements of SST include:

- Assumption of Multiplicity – Unlike models that see a unitary personality as ideal, SST normalizes and even celebrates the mind’s natural multiplicity. It provides a compassionate way of understanding the different, often conflicting parts of the psyche.

- Focus on the Self – SST is unique in its belief that everyone has a core Self that cannot be damaged by trauma. The Self is seen as the main healing agent – the therapist’s role is to support the client’s Self-leadership rather than be an expert.

- Emphasis on Embodied Experience – SST relies heavily on body sensations, imagery, and other experiential ways of knowing. It trusts that the inherent wisdom of the system will emerge from within, rather than imposing theory or direction from the outside.

- No Bad Parts Philosophy – All parts, even ones manifesting destructive behaviors, are seen as valuable and well-intentioned. SST aims to understand the protective role of each part rather than eliminate them.

- Unburdening Process – SST has a unique approach to trauma work that focuses on “unburdening” parts rather than just desensitizing triggers. Exiles release the traumatic memories, emotions, and negative beliefs they’ve been holding, often through creative imagery and ritual.

- Language of Parts – SST uses the simple, relatable language of “parts” rather than jargon like ego states, modes, subpersonalities, etc. The idea that we all have different parts is an intuitive framework most clients can understand.

- Applicability to Non-Clinical Populations – Because the model is non-pathologizing and affirming of human diversity, SST translates well outside of therapy to fields like coaching, education, social work, organizational development, and spiritual direction.

While SST shares common factors with other therapies, its particular combination of the elements above make it a unique approach that many clients find deeply transformative.

Some of the forgotten or underemphasized aspects of SST that may be relevant to modern practice include:

- Greater attention to the therapist’s own parts and how they interact with the client’s system. Emphasis on the therapist’s Self-led presence.

- Recognizing the role of systemic trauma and working with legacy/cultural burdens. Expanding our view of what gets exiled.

- Potential for bringing SST perspectives into fields like social justice work, diversity initiatives, community organizing, etc. A parts-informed view of conflict and polarization.

- More research on SST’s potential as a preventative model for building Self-leadership capacities in non-clinical populations like children, parents, teachers, leaders. Developing “parts literacy.”

- Exploring the spiritual dimensions of SST more explicitly and studying how it interfaces with different wisdom traditions. The Self has similarities to constructs like Buddha nature, Christ consciousness, Atman, etc.

As our culture becomes increasingly fast-paced, fragmented, and complex, SST’s focus on slowing down, going within, and compassionately embracing all our parts may be more relevant than ever. Its message that there are no bad parts, only parts trying their best to protect us, can be deeply healing in an world of criticism and division. Learning to unblend from our parts and access Self-energy provides a much-needed path to presence and peace.

While no model is one-size-fits-all, SST has a track record of facilitating transformation for clients who have spent years feeling stuck and hopeless. As Dr. Schwartz writes:

“One of the things I love about SST is that it’s a fearless approach. We don’t have to be afraid of our inner worlds anymore. In fact, each part, no matter how destructive it might be acting, has an essential gift to offer the system. Our parts are not our enemies. They’re our greatest teachers and allies. When we get to know them with compassionate curiosity, their wisdom enriches our life.”

In a world that often encourages us to be at war within – to exile certain parts while overidentifying with others – SST offers a radical path to inner peace. It provides a much-needed framework for Self-leadership in the 21st century.

References

Giddens, M. (2012). Eating disorders and internal family systems therapy. In A. Rambo, C. West, A. Schooley & T. V. Boyd (Eds.), Family therapy review: Contrasting contemporary models. (pp. 205–207). Taylor and Francis.

Hsieh, M. Y. & Cheng, Y. (2019). A preliminary study on the effects of internal family systems therapy on depression and anxiety. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 30(3), 176-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/08975353.2019.1616076

Lucero, R., Jones, A. C. & Hunsaker, J. A. (2018). Using Internal Family Systems theory in the treatment of combat veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and their families. Contemporary Family Therapy, 40(3), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-017-9424-z

Merscham, C. (2010). Internal family systems with children in the playroom. Play Therapy: Magazine of the British Association of Play Therapists, 63, 8–11.

Perlinski, D. P. (2011). Integrating internal family systems and harm reduction to treat substance abuse. US: ProQuest Information & Learning.

Shadick, N. A., Sowell, N. F., Frits, M. L., Hoffman, S. M., Hartz, S. A., Booth, F. D., & … Schwartz, R. C. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of an internal family systems-based psychotherapeutic intervention on outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: A proof-of-concept study. The Journal of Rheumatology, 40(11), 1831–1841. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.121465

Schwartz, R. C. (1995). Internal family systems therapy. Guilford Press.

Schwartz, R. C. (2001). Introduction to the Internal Family Systems model. Oak Park IL: Trailheads Publications, The Center for Self Leadership.

Schwartz, R. C. (2019). No bad parts: Healing trauma and restoring wholeness with the Internal Family Systems model. Sounds True.

Schwartz, R. C., Pandit, A. & Sweezy, M. (2018). Basic principles of internal family systems therapy. In J. N. Lester & M. D. Pompeo (Eds.), The handbook of systemic family therapy. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119438519.ch27

0 Comments