The Crunch Under Your Boots: What “Japanese Rock Beetles” Teach Us About the Human Mind

If you live in Alabama, you know the sound. It’s a dry, brittle crunch under your socked foot as you walk across the living room carpet in January. You look down, and there it is—an orange beetle with a little “M” painted on its neck, belly-up and twitching.

We call them ladybugs, but deep down, we know they aren’t the polite nursery rhyme bugs that fly away home. These are Asian Lady Beetles (Harmonia axyridis), though I’ve heard plenty of folks around Birmingham and Huntsville call them “Japanese rock beetles.” They swarm our windows, stain our curtains yellow, and, unlike our native ladybugs, they bite.

But why are they here? And why do they seem determined to break into our homes just to die in the corner of the ceiling fan?

The answer is a tragic story of good intentions gone wrong—a story about importing “solutions” without understanding the system. It’s the exact same story as Kudzu, and believe it or not, it’s one of the most important metaphors for your mental health.

| Feature | Native Ladybugs (e.g., Hippodamia convergens) | Asian Lady Beetle (Harmonia axyridis) |

| Origin | North America (Indigenous) |

East Asia (Imported 1916–1990s) 11 |

| Pronotal Markings | Two distinct white dashes or lines; rarely connected. |

Distinct black “M” or “W” shape on white background.8 |

| Coloration | Typically consistent red/orange with fixed spot patterns. |

Highly Polymorphic: Yellow, Orange, Red; 0–19 spots.1 |

| Winter Behavior | Solitary or small groups; burrows in leaf litter/ground. |

Aggregates in thousands; invades structures/cliffs.13 |

| Defensive Mechanism | Mild reflex bleeding; generally docile. |

Noxious yellow fluid (reflex bleeding); Bites skin.2 |

| Ecological Impact | Balanced component of local food web. |

Aggressive competitor; displaces/eats native larvae.15 |

The Kudzu of the Insect World

To understand the beetle, you have to look at the vine. In the 1930s, the South was bleeding red clay. Erosion was washing our farms into the river. So, the government brought in a “miracle vine” from Asia called Kudzu. It was supposed to anchor the soil. And it did! It did its job perfectly. But nobody asked, “What happens after it stops the erosion?” We didn’t understand the ecology; we just wanted a quick fix for a single problem. Now, we have telephone poles that look like green ghosts and forests suffocated by the “vine that ate the South.”

Fast forward to the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. Farmers in the South were battling aphids on pecan trees and crops. The USDA thought, “Hey, we have an erosion solution; let’s get an aphid solution.” They released millions of Harmonia axyridis—the Asian Lady Beetle.

Just like Kudzu, the beetles worked. They ate the aphids. But nature doesn’t work in straight lines. When you introduce a drastic change to a complex system, you don’t just solve one problem; you ripple out into a dozen new ones. We imported a predator that out-competes our native species and invades our homes by the thousands. We tried to engineer nature, and nature eventually moved into our spare bedroom.

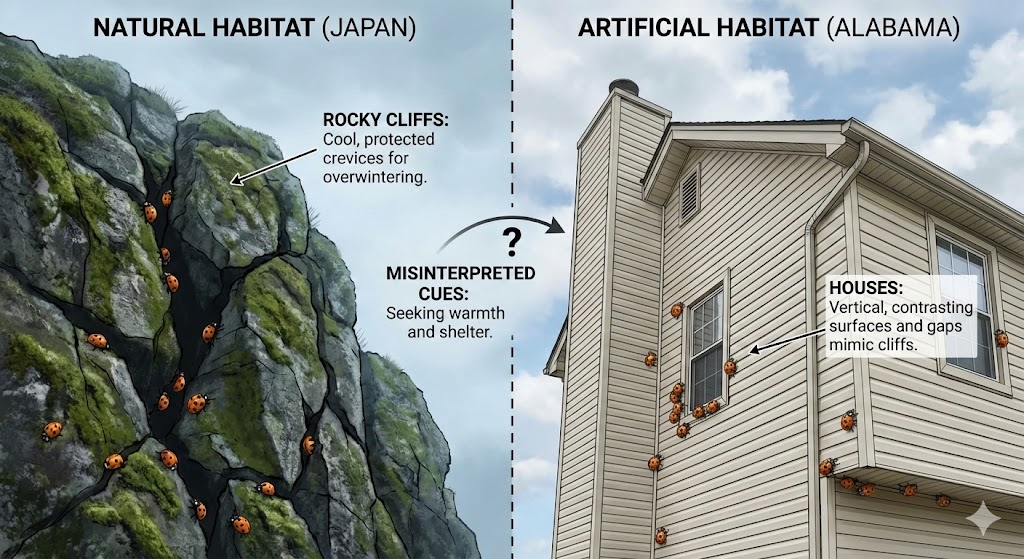

The Tragedy of the False Cliff

Here is the part that breaks my heart a little, even for a pest. You’ve probably noticed that these beetles don’t just come inside to get warm; they come inside to die. You find them desiccated on windowsills, dehydrated and exhausted.

This happens because of a biological case of mistaken identity.

In their native home of Japan and Siberia, these beetles overwinter in limestone cliffs and rocky outcroppings. They are programmed by millions of years of evolution to look for a “macro-site”—a giant, light-colored vertical surface contrasting against the dark woods. When they find one, they crawl into the deep, cool cracks of the rock to hibernate.

Alabama doesn’t have many limestone cliffs in the suburbs. But do you know what looks exactly like a limestone cliff to a beetle?

A white or tan vinyl-sided house standing in a clearing is a “super-stimulus.” It triggers their cliff-finding instinct harder than a real rock ever could. They swarm the south-facing walls because that’s where the sun would hit the rock. They crawl into the cracks (your siding, your attic vents) thinking they are entering a cool, stable rock fissure.

But your house isn’t a rock. It’s heated.

When they get inside the walls or the living room, the warmth (68–72°F) tricks their metabolism. Their bodies think it’s spring. They wake up. They burn through their fat reserves rapidly, flying around your light fixtures looking for food and water that isn’t there. They starve and dehydrate to death because they mistook a drastic artificial change for a natural refuge.

Native Wisdom vs. Imported Chaos

| Kudzu (Pueraria montana) | Asian Lady Beetle (Harmonia axyridis) | |

| Introduction Era |

Late 1800s; Promoted 1930s–50s. |

Early 1900s; Promoted 1960s–90s. |

| Promoting Agency | Soil Erosion Service / USDA. | USDA / Ag Experiment Stations. |

| Target Problem | Soil Erosion (Red Clay Runoff). | Arboreal Aphids (Pecans/Crops). |

| Specific Mechanism | Rapid vegetative growth (1 ft/day). | Aggressive predation / Rapid reproduction. |

| Unintended Consequence | Smothering of native flora/structures. | Home invasion, biting, native displacement. |

| Psychological Metaphor | Over-defense: A coping mechanism that chokes growth. | Iatrogenesis: A “cure” that becomes a pest. |

You might wonder, “Why don’t the regular red ladybugs do this?”

Our native ladybugs (like the Convergent Lady Beetle) evolved here. They know this landscape. They don’t look for cliffs that don’t exist. When winter comes, they burrow. They dig down into the leaf litter, under logs, or into the base of bunch grasses. They stay outside, grounded, connected to the earth.

The native beetle knows how to survive the Alabama winter because it is of the system. The imported beetle tries to survive by climbing a fake cliff and ends up burning itself out.

The Psychology of Ecology

So, what does this have to do with psychotherapy?

In therapy, we often treat the mind like a pecan orchard. We have “aphids”—anxiety, grief, a bad habit, a painful memory. We want them gone. So, we look for a “beetle.” We look for a drastic, imported solution to kill the problem quickly.

Maybe it’s a crash diet. Maybe it’s a new relationship we jump into to kill the loneliness. Maybe it’s a substance we use to numb the stress. Maybe it’s a rigid new personality we adopt—”I’m going to be a Tough Guy now so nobody can hurt me.”

These are invasive species in your psyche.

Just like the Asian Lady Beetle, these solutions might actually work at first. The “Tough Guy” act might stop people from bullying you (eating the aphids). But then, winter comes.

That rigid defense mechanism doesn’t know how to “burrow” and rest. It stays active all the time. It invades your home life. You find yourself snapping at your spouse or unable to be vulnerable with your kids. Your “solution” has become a swarm. You burn out, metabolically and emotionally, because you are running a high-energy defense in a season where you should be resting.

Be Careful with Drastic Changes

The lesson of the Japanese rock beetle is a lesson in the Psychology of Ecology.

Before you make a drastic change to your life—before you import a “savior” to fix your problems—you have to understand the ecosystem you already have.

-

Don’t just kill the aphids: Ask why they are there. Is the soil (your environment) unhealthy?

-

Respect the Native Self: The parts of you that want to “burrow” and hide under the covers sometimes aren’t weak. They are native. They know how to survive the winter. Don’t try to force them to climb a cliff of toxic positivity.

-

Watch for Unintended Consequences: If you suppress an emotion too hard (like we suppressed erosion with Kudzu), it will pop out somewhere else—usually in your living room, buzzing against the glass, demanding to be seen.

Real change isn’t about importing a foreign beetle to fight a war in your head. It’s about tending the soil so the native plants can grow again. It’s slower than releasing a swarm, but I promise you—it leaves a lot less mess to clean up in the spring.

0 Comments