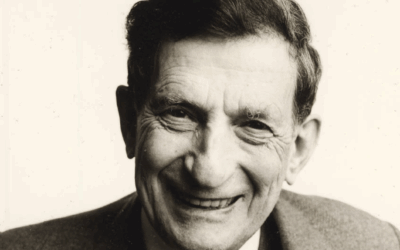

The Renegade of the Psyche

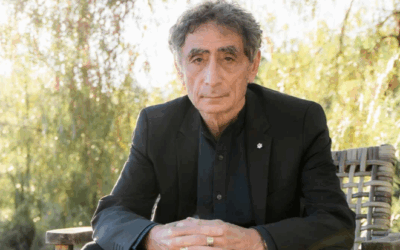

In the quiet, often reverent halls of analytical psychology, James Hillman (1926–2011) was the shout that shattered the silence. He was a Jungian who dared to critique Jung, a psychologist who argued that therapy often makes things worse, and a philosopher who demanded we stop trying to “cure” the soul and start listening to it.

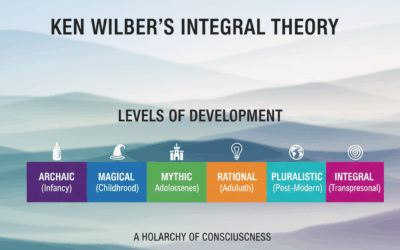

Hillman is the founder of Archetypal Psychology, a movement that sought to “re-vision” psychology not as a medical science, but as a poetic activity. While Jung focused on the Self as a unifying center, Hillman celebrated the **polytheism** of the psyche—the idea that we are inhabited by a multitude of gods, myths, and figures, none of whom should be silenced by the ego.

I have a complex relationship with Hillman’s work at Taproot Therapy Collective. I have interviewed his son, Laurence Hillman, and his prominent student David Tacey. Hillman’s insistence that we return psychology to the “street” and the “world” remains his most vital legacy.

Biography & Timeline: James Hillman (1926–2011)

Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Hillman served in the US Navy Hospital Corps before moving to Europe. He studied at the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich, eventually becoming its Director of Studies—the first American to hold the post. However, in the 1970s, he broke away from the “Zurich School” to form a more radical, image-based psychology.

Hillman felt that classical Jungian analysis had become too focused on the “heroic” ego and spiritual ascension. He wanted to drag psychology back down into the “Vale of Soul-Making” (a term borrowed from Keats). He argued that depression, anxiety, and pathology were not illnesses to be eradicated, but necessary expressions of the soul’s depth.

Key Milestones in the Life of James Hillman

| Year | Event / Publication |

| 1926 | Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey. |

| 1959 | Receives Ph.D. from the University of Zurich; becomes Director of Studies at the C.G. Jung Institute. |

| 1970 | Publishes The Myth of Analysis, a scathing critique of the analytic profession. |

| 1975 | Publishes Re-Visioning Psychology, his magnum opus establishing Archetypal Psychology. |

| 1978 | Co-founds the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture. |

| 1996 | Publishes The Soul’s Code, introducing the “Acorn Theory” to the general public. |

| 2011 | Dies in Connecticut, leaving a legacy of over 25 books. |

Major Concepts: The Acorn and the Underworld

The Acorn Theory (The Daimon)

In his bestseller The Soul’s Code, Hillman proposed the Acorn Theory. This is the idea that each person is born with a unique character or “daimon” that calls them to a specific destiny, just as an acorn holds the pattern of the oak.

- The Calling: Psychological symptoms often arise because we are refusing the call of our daimon. The “bad behavior” of a child might be the acorn trying to crack its shell.

- Against Victimhood: Hillman argued against the “parental fallacy”—the idea that we are solely the product of our upbringing. He believed we choose our parents because they provide the necessary friction for our soul’s unfolding.

The Poetic Basis of Mind

Hillman argued that the psyche is not a biological machine but a poetic reality. We live in a world of images.

Clinical Application: In therapy, we don’t ask “Why did this happen?” (cause/effect). We ask “What does this image want?” If a patient dreams of a black dog, we don’t reduce it to “depression.” We interact with the dog as a living, autonomous presence.

The Conceptualization of Trauma: Pathologizing as Soul-Work

Hillman’s view of trauma is perhaps his most controversial and liberating contribution. He argued that the psyche has a natural “pathologizing function.”

The Necessity of Falling Apart

We are obsessed with health, wholeness, and integration. Hillman argued that the soul needs to fall apart. Depression, anxiety, and fragmentation are ways the soul deepens itself.

The Underworld: In his book The Dream and the Underworld, he critiques the heroic ego that wants to “conquer” trauma. Instead, he suggests we must descend into the underworld of the symptom. Trauma is an initiation into the imaginal realm.

Anima Mundi: The Trauma of the World

Later in life, Hillman shifted to Ecopsychology. He argued that much of our anxiety is not personal, but a reaction to the destruction of the Anima Mundi (World Soul). If the world is dying, of course we feel sick.

Therapy beyond the Room: Healing requires reconnecting with the beauty and soul of the world. We cannot be healthy individuals on a sick planet.

Legacy: Psychology as Art

Hillman liberated psychology from the clinic. He returned it to the streets, to architecture, to politics, and to art. He taught us that the goal of life is not to be “normal,” but to have character.

By engaging with his work, we learn that our symptoms are not errors. They are the “gods” pressing for recognition. As Hillman famously said, “The gods have become diseases; Zeus no longer rules Olympus but rather the solar plexus, and produces curious specimens for the doctor’s consulting room.”

Further Reading & Resources

- Pacifica Graduate Institute: Home of the James Hillman Collection.

- Spring Publications: Publisher of Archetypal Psychology.

- James Hillman Symposium: Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture.

0 Comments