The Evolution of Psychoanalytic Thought: From Freud’s Drive Theory to Contemporary Relational Models

What is Psychoanalysis like Now?

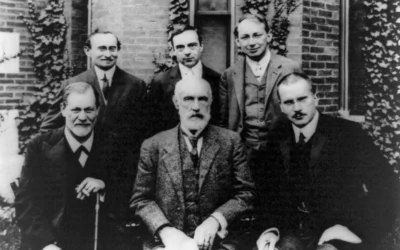

Psychoanalysis, the field founded by Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, has undergone a remarkable evolution over the past 100+ years. Far from being a fixed set of doctrines, psychoanalytic theory has been characterized by ongoing revision, expansion, and at times outright repudiation of earlier ideas. This paper traces this complex evolution, arguing that while classical Freudian drive theory has been largely abandoned, the psychoanalytic tradition continues to offer generative frameworks for conceptualizing development, psychopathology, and the process of therapeutic change.

Freud’s Unstable Theoretical Edifice

As Frederick Crews details in his critical biography “Freud: The Making of an Illusion” (2017), Freud’s career was marked by a series of dramatic theoretical reversals and unsubstantiated claims. Some key examples:

- Freud initially argued that all neuroses were caused by repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse, only to subsequently claim that his patients’ abuse reports were fantasies representing Oedipal wishes.

- He postulated a model of psychosexual development with rigid, universal stages, then made this schematic less definitive.

- Freud saw all dreams as wish fulfillments before revising his theory to include dreams that represented punishment or trauma.

- His structural model went through numerous revisions in terms of the names, number and functions of agencies like the ego and superego.

Crews sees these shifts not as evidence of scholarly growth but as reflective of a fundamentally unscientific approach characterized by unchecked speculation and resistance to empirical testing. Yet while Freud’s specific formulations were problematic, many of his general insights – the shaping role of childhood experience, the existence of unconscious mental processes, the meaningful nature of symptoms and dreams – proved lastingly generative.

The Emergence of Object Relations Theory

Some of the most important developments in psychoanalysis came from the object relations school, which shifted emphasis from instinctual drives to the structuring role of human relationships. Major object relations theorists included:

Melanie Klein (1882-1960)

Klein pioneered the psychoanalysis of children and developed an influential model of psychological development. She argued that infants from birth were object-related, experiencing the world through unconscious phantasies about others. Klein saw development unfolding through two key positions:

- The paranoid-schizoid position of the first months of life, characterized by polarized all-good/all-bad representations and persecutory anxiety.

- The subsequent depressive position, in which the infant realizes the mother is a whole object who can be both good and bad, leading to guilt, concern, and the desire to make reparation.

Klein’s ideas were highly controversial, but she advanced psychoanalytic understanding of primitive mental states, aggression, and the complex inner world of the child.

Donald Winnicott (1896-1971)

Winnicott emphasized the importance of the early holding environment provided by the “good-enough mother” who intuitively meets her baby’s needs. This facilitates the development of a “true self” able to maintain existential aliveness and playfulness. Winnicott also highlighted the developmental role of transitional objects and phenomena, viewing play as the foundation of creativity and self-experience.

For Winnicott, the therapist’s job was not to offer authoritative interpretations but to facilitate a “holding environment” in which the patient’s suppressed true self could emerge. This represented a significant humanization of psychoanalytic practice.

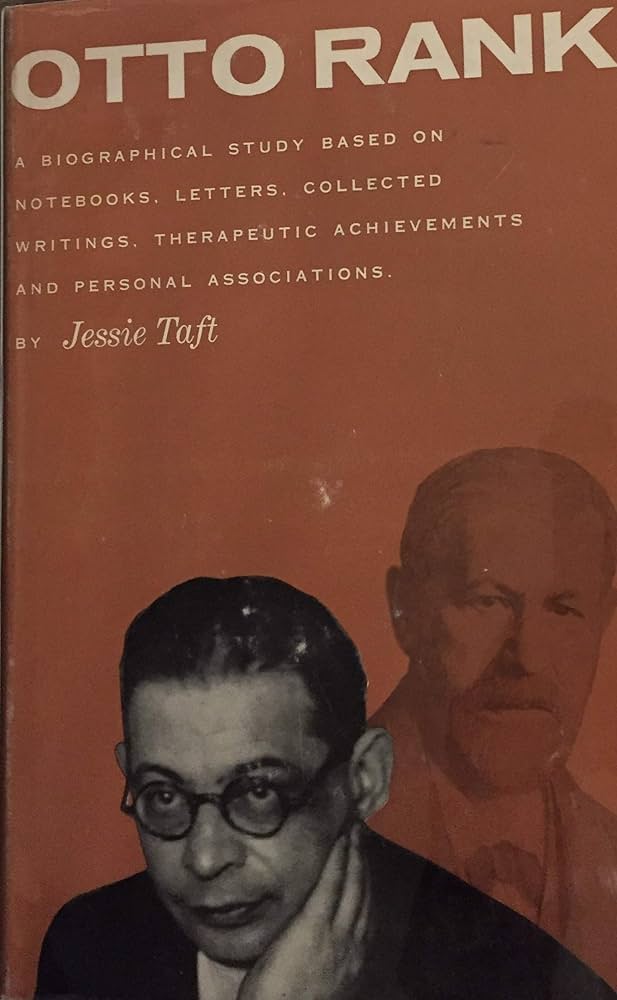

Otto Rank (1884-1939)

Rank was an early follower of Freud who came to challenge many of his basic assumptions. He saw the central human struggle not in terms of drive but as a conflict between the fear of life and the fear of death, with anxiety arising from the trauma of birth. Rank emphasized the importance of pre-Oedipal development and the creative impulse, seeing will and creativity as central to therapeutic change.

Rank developed a briefer, more active form of therapy focused on the healing properties of the therapeutic relationship itself. His ideas foreshadowed later developments in existential-humanistic psychology.

Karen Horney (1885-1952)

Horney challenged Freud’s views on female development, arguing that girls envy male privilege rather than anatomy, and that the Oedipus complex was more culturally variable than universal. She developed a model of neurosis based on basic anxiety and the psychic defenses mobilized to cope with it.

Horney outlined three broad neurotic solutions: moving towards, against, or away from others. She emphasized both cultural shaping and the individual’s self-actualizing tendency, with therapy aiming to restore the patient’s thwarted growth potential.

Margaret Mahler (1897-1985)

Mahler systematized an influential model of infant development, seeing psychological birth as a phased process of separation-individuation unfolding over the first three years of life. She described an initial “normal autistic phase” followed by a symbiotic phase of undifferentiated union with the mother.

Gradual separation-individuation then occurred through four subphases – differentiation, practicing, rapprochement, and consolidation of individuality – each with its own developmental tasks and typical challenges. Mahler provided an intricate model of how the self emerges through the early mother-child matrix.

Further Expansions and Reformulations

Other psychoanalytic pioneers helped transform the field by integrating insights from areas like developmental psychology, cognitive science, and attachment theory. Key figures included:

Erik Erikson (1902-1994)

Erikson expanded Freud’s five psychosexual stages into an eight-stage model encompassing the entire life cycle from infancy to old age. Each stage was defined by a central psychosocial crisis (e.g. trust vs. mistrust in infancy) that the individual must optimally resolve to progress.

Erikson placed far more emphasis than Freud on the role of society and culture in shaping development, and his epigenetic model continues to be highly influential.

John Bowlby (1907-1990)

Bowlby integrated evolutionary theory and ethology to develop a fundamentally new understanding of the mother-infant bond. He argued that attachment was an innate behavioral system with a protective evolutionary function, not a derivative of feeding or sexuality as Freud had assumed.

Bowlby showed how different patterns of attachment (secure vs. various insecure forms) shaped social and emotional development via internalized “internal working models.” His ideas were expanded by Mary Ainsworth, Mary Main and others to form a highly empirically-validated model of relational functioning.

Heinz Kohut (1913-1981)

Kohut challenged classical analytic assumptions by arguing that Freud’s drive/conflict model did not capture the experience of his narcissistic patients, whose suffering reflected not Oedipal guilt but deficits in the self-structure. Kohut saw the self as the core of personality, developing through the internalization of mirroring, idealizing, and twinship “self-object” relationships.

For Kohut, narcissistic disorders reflected faulty self-development due to empathic failures, not repressed drives. The therapist’s role was to provide empathic attunement and understanding within a collaborative framework.

Harry Stack Sullivan (1892-1949)

Sullivan developed one of the first comprehensive interpersonal theories of personality and psychotherapy. He argued that personality developed through recurrent interactions with others, especially early caregivers, with the individual internalizing patterns of relating that could foster or undermine self-esteem and the development of mutuality.

Psychopathology resulted from disturbances in interpersonal relations, with the individual deploying security operations like selective inattention to ward off anxiety. The goal of therapy for Sullivan was the collaborative disconfirmation of the patient’s pathogenic assumptions through the analysis of the therapy relationship itself.

The Relational Turn

In the 1980s, psychoanalysis took a “relational turn,” with a new generation of theorists drawing on feminism, postmodernism, and infant research to challenge the one-person assumptions of classical analysis. Key relational ideas included:

- Viewing development as inherently intersubjective, with self-organization always occurring in relation to others.

- Challenging the notion of a fully asocial unconscious in favor of seeing the mind as inherently dyadic and dialogic.

- Providing a more social constructionist view of gender and sexuality instead of the essentialism and heteronormativity of classical analytic thought.

- Seeing therapeutic change as occurring not just through insight and working through conflict but through the lived experience of new relational possibilities.

- Placing the therapy relationship itself at the center of the change process, with its enactments and moments of meeting providing a developmental second chance.

Relational thinkers like Steven Mitchell, Lewis Aron, Jessica Benjamin, and Donnell Stern helped shift psychoanalysis towards a more egalitarian, two-person model that emphasized mutuality and co-construction. This entailed a changed view of the therapist’s role from objective authority to collaborator in an uncertain intersubjective encounter.

Psychoanalysis in the 21st Century

In the 21st century, psychoanalysis continues to evolve in response to both internal critique and outside empirical advances. There is growing recognition of the need for evidential support for theoretical claims, and increasing integration of findings from cognitive science, neuroscience, developmental psychology, and other fields.

Psychodynamic researchers have demonstrated the efficacy of psychoanalytic therapies for many conditions, though work remains to specify mechanisms of change. There is also growing attention to the impact of culture, race, gender, and sexual orientation on development and clinical process.

Amid this change, core psychoanalytic insights endure – the existence of unconscious mental life, the shaping force of early relationships, the repetition of old relational patterns, the meaningful nature of symptoms and dreams. Perhaps the most lastingly generative aspect of Freud’s legacy is his depiction of human beings as conflicted, multi-layered creatures often driven by forces we don’t understand.

At its best, contemporary psychoanalysis provides a rich, non-reductive vocabulary for reflecting on subjectivity, meaning-making, and the vicissitudes of the human condition. While many classical formulations have rightly fallen away, the psychoanalytic sensibility continues to offer an unparalleled exploratory space for grappling with the complexities of the mind.

Legacy of Psychoanalysis

While much of Freud’s original theoretical edifice has been dismantled or heavily revised, perhaps his most enduring legacy was opening up the realm of the dynamic unconscious and inner representational world. Freud’s pioneering work allowed subsequent generations of psychoanalytic thinkers to explore this territory in much greater depth and nuance. What emerged from these explorations was a growing recognition that the central psychoanalytic task was not so much making the unconscious conscious, but rather helping the individual align their internal object world with external reality.

This insight developed through the work of the object relations theorists, who saw the psyche as fundamentally shaped by internalized representations of self and other. Figures like Melanie Klein, Donald Winnicott, and Ronald Fairbairn argued that psychological well-being depended on the degree of congruence between one’s inner object world and actual interpersonal experience. When early relational trauma or deprivation led to the internalization of punitive, withholding, or inconsistent object representations, the individual was left struggling to meaningfully connect with others or develop a cohesive sense of self.

For the object relations theorists, the therapeutic task involved a gradual remodeling of the inner object world through the provision of “good enough” relational experiences. The therapist served as a new object who could help metabolize toxic introjects and foster the development of a more benign, reality-attuned representational world. This did not occur through insight alone, but through the lived experience of a different kind of relationship.

Heinz Kohut’s self psychology took this idea in a more existential direction, seeing psychopathology as rooted in a defensive retreat from the painful recognition of the separateness and limitedness of the self. For Kohut, early empathic failures led the individual to cling to an archaic, grandiose self rather than accept the sobering realities of the outer world. The therapist’s empathic attunement and appreciation for the patient’s subjective experience was seen as key to strengthening the self-structure and facilitating a more mature accommodation to reality.

The British object relations tradition developed by Winnicott and Fairbairn placed less emphasis on the drives and saw development in terms of a fundamental need for connection and dependence. In this view, the child’s inner fantasy life was not a defensive flight from reality, but a creative attempt to preserve a sense of connection in the face of environmental failure. The therapy process involved the symbolic “survival” of the therapist in the face of the patient’s destructive attacks, allowing for the gradual relinquishment of omnipotent control and the development of a more genuine relatedness.

Attachment theory, pioneered by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, grounded object relations concepts in the empirical study of infant-caregiver interactions. Bowlby saw attachment as a primary motivational system rooted in evolutionary imperatives, with different attachment styles representing adaptations to the contingencies of the early environment. Secure attachment fostered an inner representational world that allowed for the metabolization of distress and the capacity to draw on internalized “secure base” representations for emotional regulation and interpersonal connection.

The relational turn in psychoanalysis took these ideas in a more radically interpersonal direction, challenging the notion of a “one-person psychology” in favor of seeing the mind as fundamentally dyadic and intersubjective. Relational thinkers like Stephen Mitchell argued that there was no fully inner world wholly distinct from external reality; rather, the psyche existed in the intersubjective “third space” between self and other. Therapeutic change was seen as occurring not through insight or the alteration of internal representations, but through the co-construction of new intersubjective possibilities.

Freud’s break with his early collaborators – Adler, Jung, and Rank – foreshadowed these later developments. Alfred Adler’s individual psychology emphasized the innate human striving for connection and the impact of early experiences of inferiority and compensatory striving. Carl Jung saw the goal of therapy as achieving a higher state of consciousness and connection with the collective unconscious, a more expansive vision of inner life than Freud’s. And Otto Rank placed the fundamental human conflict between the fear of life and death, seeing creativity and will as the central therapeutic agents.

While much of Freudian theory has fallen away, the psychoanalytic tradition has endured by way of an evolving attentiveness to the dialectical interaction between inner and outer worlds. Whether through the remodeling of internal object representations, the strengthening of self-structure, the provision of corrective relational experiences, or the co-construction of new intersubjective realities, the central psychoanalytic task has been reorienting the individual to a shared existential reality. This overarching mission – rather than any specific Freudian formulation – is what continues to give psychoanalysis its remarkable potency and depth as a theory of mind and method of healing.

The history of psychoanalysis is one of continual evolution and reinvention. Freud’s initial insights – as problematic as many were – opened up the realm of the dynamic unconscious and provided a new way of thinking about inner life. Subsequent generations of analysts revised and expanded on this vision, drawing on a range of empirical and conceptual innovations.

Object relations theory shifted the focus to the structuring role of human relationships in shaping the psyche. Later developments integrated insights from attachment research, cognitive science, and studies of mother-infant interaction. The relational turn of recent decades has led to a more intersubjective model of mind and a greater emphasis on the mutuality and co-constructive process of therapy.

Through all these changes, psychoanalysis has preserved its emphasis on attending to unconscious experience, making meaning of personal history, and working through entrenched patterns of relating and defending. At its core, it remains a practice of depth psychology – an attempt to illuminate the complex, conflictual, often irrational workings of the human mind.

While psychoanalysis must continue evolving in light of empirical advances, its unique clinical sensibility and rich theoretical resources ensure its enduring relevance. As a method for exploring the inner world and catalyzing psychological change, psychoanalysis remains unparalleled. Its future development will undoubtedly entail ongoing revisions and reformulations – but such is the inescapable character of any living tradition.

Bibliography

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Aron, L. (1996). A meeting of minds: Mutuality in psychoanalysis. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

Benjamin, J. (1988). The bonds of love: Psychoanalysis, feminism, and the problem of domination. New York: Pantheon.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

Crews, F. (2017). Freud: The making of an illusion. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Eagle, M. (2011). From classical to contemporary psychoanalysis: A critique and integration. New York: Routledge.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1952). Psychoanalytic studies of the personality. London: Tavistock.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization and the development of the self. New York: Other Press.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. Standard Edition, 4-5. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Standard Edition, 7. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. Standard Edition, 19. London: Hogarth Press.

Greenberg, J. R., & Mitchell, S. A. (1983). Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Guntrip, H. (1971). Psychoanalytic theory, therapy, and the self. New York: Basic Books.

Horney, K. (1950). Neurosis and human growth: The struggle toward self-realization. New York: Norton.

Klein, M. (1975). The writings of Melanie Klein (4 vols.). New York: The Free Press.

Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

Mahler, M., Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1975). The psychological birth of the human infant: Symbiosis and individuation. New York: Basic.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points in attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 66-106.

Mitchell, S. A. (1988). Relational concepts in psychoanalysis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ogden, T. H. (1986). The matrix of the mind: Object relations and the psychoanalytic dialogue. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson.

Rank, O. (1929). The trauma of birth. London: Routledge.

Segal, H. (1964). Introduction to the work of Melanie Klein. London: Heinemann.

Stern, D. N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant: A view from psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. New York: Basic Books.

Stolorow, R. D., & Atwood, G. E. (1992). Contexts of being: The intersubjective foundations of psychological life. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. New York: International Universities Press.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. London: Tavistock.

Further Reading

Bromberg, P. M. (2011). The shadow of the tsunami: And the growth of the relational mind. New York: Routledge.

Coates, S. W. (2016). Can babies remember trauma? Symbolic forms of representation in traumatized infants. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 64(4), 751-776.

Ehrenberg, D. B. (2010). Working at the “intimate edge”: Intersubjective considerations in relational psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 20(1), 92-104.

Ferro, A. (2006). Psychoanalysis as therapy and storytelling. New York: Routledge.

Frank, C. (2014). On the reception of the concept of the death drive in Germany: expressing and resisting an ‘evil principle’? The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 95(3), 425-444.

Gabbard, G. O., & Westen, D. (2003). Rethinking therapeutic action. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 84(4), 823-841.

Hoffman, I. Z. (1983). The patient as interpreter of the analyst’s experience. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 19(3), 389-422.

Kernberg, O. F. (2014). Narcissistic defenses in the psychoanalytic situation. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 95(3), 529-551.

Laplanche, J. (1989). New foundations for psychoanalysis. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Levenson, E. A. (1991). The purloined self: Interpersonal perspectives in psychoanalysis. New York: Contemporary Psychoanalysis Books.

Mitchell, S. A. (1993). Hope and dread in psychoanalysis. New York: Basic Books.

Orange, D. M. (2010). Thinking for clinicians: Philosophical resources for contemporary psychoanalysis and the humanistic psychotherapies. New York: Routledge.

Pizer, S. (1998). Building bridges: The negotiation of paradox in psychoanalysis. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

Sandler, J., & Sandler, A. M. (1998). Internal objects revisited. London: Karnac Books.

Stolorow, R. D. (2007). Trauma and human existence: Autobiographical, psychoanalytic, and philosophical reflections. New York: The Analytic Press.

Sugarman, A. (2016). Psychoanalysis as a general psychology: Key concepts and their applicability beyond the consulting room. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 36(5), 362-376.

Summers, F. (2015). Object relations theories and psychopathology: A comprehensive text. New York: Routledge.

Wolson, P. (1996). Impasse and innovation in psychoanalysis: Clinical case seminars. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

Classical Psychoanalytic Theory

- Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. Standard Edition, 4-5. London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Standard Edition, 7. London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1914). On narcissism: An introduction. Standard Edition, 14. London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle. Standard Edition, 18. London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. Standard Edition, 19. London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1926). Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety. Standard Edition, 20. London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1933). New introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. Standard Edition, 22. London: Hogarth Press.

Ego Psychology

- Hartmann, H. (1939). Ego psychology and the problem of adaptation. New York: International Universities Press.

- Hartmann, H., Kris, E., & Loewenstein, R. M. (1946). Comments on the formation of psychic structure. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 2(1), 11-38.

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

- Jacobson, E. (1964). The self and the object world. New York: International Universities Press.

Object Relations Theory

- Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1952). Psychoanalytic studies of the personality. London: Tavistock.

- Klein, M. (1975). The writings of Melanie Klein (4 vols.). New York: The Free Press.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. New York: International Universities Press.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. London: Tavistock.

- Guntrip, H. (1971). Psychoanalytic theory, therapy, and the self. New York: Basic Books.

- Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York: Jason Aronson.

- Mahler, M., Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1975). The psychological birth of the human infant: Symbiosis and individuation. New York: Basic.

- Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

- Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books.

Self Psychology

- Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

- Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

- Kohut, H. (1984). How does analysis cure? Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Stolorow, R. D., Brandchaft, B., & Atwood, G. E. (1987). Psychoanalytic treatment: An intersubjective approach. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Bacal, H. A., & Newman, K. M. (1990). Theories of object relations: Bridges to self psychology. New York: Columbia University Press.

Relational Psychoanalysis

- Greenberg, J. R., & Mitchell, S. A. (1983). Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mitchell, S. A. (1988). Relational concepts in psychoanalysis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Aron, L. (1996). A meeting of minds: Mutuality in psychoanalysis. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Benjamin, J. (1988). The bonds of love: Psychoanalysis, feminism, and the problem of domination. New York: Pantheon.

- Benjamin, J. (1995). Like subjects, love objects: Essays on recognition and sexual difference. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Mitchell, S. A., & Aron, L. (Eds.). (1999). Relational psychoanalysis: The emergence of a tradition. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Ghent, E. (1992). Paradox and process. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 2(2), 135-159.

- Hoffman, I. Z. (1998). Ritual and spontaneity in the psychoanalytic process: A dialectical-constructivist view. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Bromberg, P. M. (1998). Standing in the spaces: Essays on clinical process, trauma, and dissociation. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Stern, D. B. (2010). Partners in thought: Working with unformulated experience, dissociation, and enactment. New York: Routledge.

Intersubjectivity Theory

- Stolorow, R. D., & Atwood, G. E. (1992). Contexts of being: The intersubjective foundations of psychological life. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Stolorow, R. D., Atwood, G. E., & Brandchaft, B. (Eds.). (1994). The intersubjective perspective. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

- Stolorow, R. D. (1997). Dynamic, dyadic, intersubjective systems: An evolving paradigm for psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 14(3), 337-346.

- Orange, D. M., Atwood, G. E., & Stolorow, R. D. (1997). Working intersubjectively: Contextualism in psychoanalytic practice. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Stolorow, R. D. (2007). Trauma and human existence: Autobiographical, psychoanalytic, and philosophical reflections. New York: The Analytic Press.

Contemporary Freudian Psychoanalysis

- Brenner, C. (1982). The mind in conflict. New York: International Universities Press.

- Arlow, J. A., & Brenner, C. (1990). The psychoanalytic situation. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 59(1), 1-28.

- Busch, F. (1995). Do actions speak louder than words? A query into an enigma in analytic theory and technique. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 43(1), 61-82.

- Blass, R. B., & Blatt, S. J. (1996). Attachment and separateness in the experience of symbiotic relatedness. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 65(4), 711-746.

- Smith, H. F. (1997). Defensive fantasy as resistance to self-understanding. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 66(4), 569-590.

Attachment Theory and Research

- Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1-2), 66-104.

- Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Fonagy, P., Steele, M., Steele, H., Moran, G. S., & Higgitt, A. C. (1991). The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 12(3), 201-218.

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization and the development of the self. New York: Other Press.

Neuropsychoanalysis

- Solms, M., & Turnbull, O. (2002). The brain and the inner world: An introduction to the neuroscience of subjective experience. New York: Other Press.

- Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Damasio, A. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Philosophy and Psychoanalysis

- Ricoeur, P. (1970). Freud and philosophy: An essay on interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and human interests. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Loewald, H. W. (1980). Papers on psychoanalysis. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Cavell, M. (1993). The psychoanalytic mind: From Freud to philosophy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lear, J. (1998). Open minded: Working out the logic of the soul. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mills, J. (2005). Treating attachment pathology. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Psychoanalytic Criticism and Cultural Studies

- Lacan, J. (1977). Écrits: A selection. New York: Norton.

- Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality: Vol. 1. An introduction. New York: Pantheon.

- Žižek, S. (1989). The sublime object of ideology. London: Verso.

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kristeva, J. (1982). Powers of horror: An essay on abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

General Psychoanalytic Texts and Anthologies

- Gabbard, G. O. (2004). Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: A basic text. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Mitchell, S. A., & Black, M. J. (1995). Freud and beyond: A history of modern psychoanalytic thought. New York: Basic Books.

- Person, E. S., Cooper, A. M., & Gabbard, G. O. (Eds.). (2005). The American psychiatric publishing textbook of psychoanalysis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Chodorow, N. J. (1999). The power of feelings: Personal meaning in psychoanalysis, gender, and culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Wallerstein, R. S. (1998). Lay analysis: Life inside the controversy. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization and the development of the self. New York: Other Press.

0 Comments