When Andrew Samuels published “Jung and the Post-Jungians” in 1985, he gave the Jungian world something it desperately needed: a map of its own territory. Like many fields that emerge from a singular founding figure, analytical psychology had fractured into different camps, each claiming to represent the “true” Jung while developing in markedly different directions. Samuels’ taxonomy of three schools (later revised to four) wasn’t just academic categorization; it revealed something profound about how psychological theories evolve and, more importantly, about the nature of psychotherapy itself.

The Original Three Schools

Samuels initially identified three major streams flowing from Jung’s work, each emphasizing different aspects of his vast theoretical corpus:

The Classical School represents those who work consciously within Jung’s original framework, focusing primarily on the Self and the individuation process. This school maintains the traditional emphasis on dream work, active imagination, and the archetypal dimensions of the psyche. Analysts like Joseph Henderson, Emma Jung, Barbara Hannah, Gerhard Adler, and Esther Harding embodied this approach, staying close to Jung’s original methods while developing them further. These analysts preserved the core Jungian focus on the numinous quality of psychological experience and the centrality of the individuation journey.

The Developmental School brought analytical psychology into dialogue with psychoanalytic object relations theory, emphasizing the importance of early childhood experience and the clinical significance of transference and countertransference. Michael Fordham pioneered this approach, creating bridges between Jung and Klein, between archetype and attachment. This school recognized that before we can individuate, we need a coherent ego, and that ego emerges through early relational experiences. The developmental Jungians brought a more clinically grounded approach to working with severe pathology and early trauma.

The Archetypal School, most prominently associated with James Hillman, took Jung’s concept of the archetype and reimagined psychology itself as an archetypal activity. Rather than focusing on the hero’s journey toward wholeness, Hillman and his followers emphasized “soul-making” through deep engagement with images. Thomas Moore brought this perspective to popular consciousness, while Marion Woodman integrated it with profound body work. Clarissa Pinkola Estés explored archetypal patterns through story and folklore, Robert Bly through poetry and men’s work, and Ginette Paris through a polytheistic psychological perspective. This school was less interested in cure than in cultivating a richly imaginal life.

The Problem with Categories

But here’s where it gets interesting: Samuels himself came to recognize that these categories were, in his words, “creative fictions.” Real analysts don’t fit neatly into boxes. June Singer integrated Jungian thought with boundary theory and androgyny. Jean Shinoda Bolen wove together feminism, activism, and archetypal psychology. Robert A. Johnson made Jungian ideas accessible through simple but profound interpretations of myth. Murray Stein bridged classical and contemporary approaches. John Ryan Haule integrated Jung with phenomenology and neuroscience. Nathan Schwartz-Salant brought Jung into dialogue with borderline phenomena and subtle body experiences. Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig challenged Jungian orthodoxies while remaining deeply Jungian. Steven T Richards explored the clinical applications across different schools. James Hillman’s son Laurence Hillman fused his father’s archetypal psychology with astrology and corporate consulting and coaching.

By his own later admission, Samuels realized that within each Jungian analyst, there exists a classical analyst, a developmental analyst, and an archetypal analyst. We all contain these multiple perspectives, and good clinical work often requires moving fluidly between them.

The Revised Four Schools: Mapping the Extremes

By 2015, Samuels had revised his schema to include two new “extreme” positions that represented the dangers at either end of the spectrum:

Jungian Literalism/Fundamentalism emerged as the extreme version of the Classical school. This position rigidly adheres to Jung’s original writings as scripture, policing the boundaries of who counts as a “real Jungian.” One of the truer statements Freud made was about the “narcissism of petty differences” and that is personified by these schools of thought. Jungian fundamentalism is one of the reasons that the Jungian institutes keep rupturing, splitting, quarreling and dying out. If you’ve ever encountered someone on Reddit gatekeeping Jung by quoting Collected Works volume numbers like biblical verse, you’ve met this energy. These fundamentalists, as Samuels notes, can be “cruel and stigmatizing,” particularly in training institutes where they control who gets to call themselves Jungian. It was these models that many somatic and experiential Jungian analysts rebelled against to create models like Process Oriented Therapy and Voice Dialogue Therapy.

Jungian Merger with Psychoanalysis represents the opposite extreme, where analytical psychology becomes so absorbed into psychoanalytic thinking that it loses its distinctive character. The danger here is that the uniquely Jungian contributions (the non-literal understanding of symbols, the prospective function of the unconscious, the therapist’s disciplined use of self-disclosure) get lost in the attempt to gain psychoanalytic respectability.

Meanwhile, the Archetypal school, Samuels observed, had largely “ceased to exist” as a distinct clinical entity. Hillman’s radical reimagining of psychology had either been integrated into other approaches or abandoned as clinically unworkable. The imaginal perspective enriched the field but couldn’t stand alone as a therapeutic method.

The Mirror of Integration

What strikes me most about Samuels’ evolving taxonomy is how perfectly it mirrors a truth I’ve observed about psychotherapy more broadly: we all need to become more integrative. The “therapy wars” of the 20th century, where different schools fought for supremacy, increasingly look like a futile exercise. No single approach has all the answers because human suffering is too complex, too multifaceted, to be addressed by any single lens.

The movement from three schools to four, with the recognition of dangerous extremes, maps onto the broader field’s recognition that both rigid orthodoxy and complete theoretical dissolution are problematic. We need strong theoretical foundations (but not fundamentalism), and we need to be open to learning from other approaches (but not to the point of losing our core identity).

John Beebe’s Model of the MBTI offers insight into how this could be accomplished. This evolution in Jungian thinking reflects a deeper truth about the therapeutic process itself. Just as Samuels discovered that every analyst contains multiple schools within them, every therapeutic encounter requires navigation along multiple dimensional axes. These aren’t just theoretical constructs but lived tensions in the consulting room:

The Hero-Inferior Axis: Every patient comes with their competent, defended “heroic” mode of functioning and their vulnerable, underdeveloped “inferior” aspects. The Classical school understood this through individuation, the Developmental through early wounds and defenses, the Archetypal through the interplay of psychological complexes. Effective therapy requires meeting patients first in their strength (their “want”) before helping them develop their vulnerable edges (their “need”).

The Thinking-Feeling Axis: Some patients approach therapy as an intellectual exercise, wanting to understand and analyze. Others come seeking emotional validation and relational warmth. The Thinking types often need what Feeling offers (connection, values, empathy) while Feeling types often need what Thinking provides (clarity, boundaries, objective perspective). Each school emphasizes different ends of this spectrum, but healing requires the full range.

The Sensing-Intuition Axis: The concrete, somatic, here-and-now focus (Sensing) stands in tension with the symbolic, pattern-seeking, possibility-oriented mode (Intuition). Developmental Jungians brought more Sensing into the tradition through attention to actual early experiences. Archetypal psychologists privileged Intuition through their emphasis on image and metaphor. Classical analysts tried to hold both through attention to both personal history and archetypal patterns.

The Conscious-Unconscious Axis: Perhaps most fundamental to all depth psychology, this axis runs through each school differently. The Classical school sees it as the dialogue between ego and Self. The Developmental school tracks it through transference and countertransference. The Archetypal school finds it in the tension between literal and imaginal.

The Personal-Collective Axis: Individual suffering always occurs within collective contexts. The Developmental school emphasized personal history, the Archetypal school collective patterns, the Classical school tried to bridge both. Modern practice increasingly recognizes that we can’t separate individual psychology from cultural context, personal trauma from collective trauma, individual healing from social justice.

The Executive Control-Default Mode Axis: Contemporary neuroscience reveals what Jungians intuited: the psyche operates through different neural networks. The goal-directed, problem-solving network (executive control) corresponds to what Jung called directed thinking. The spontaneous, self-referential network (default mode) maps onto fantasy thinking and the movement of complexes. The salience network that switches between them might correspond to what Jung called the transcendent function, the psyche’s ability to hold the tension between opposites.

The Therapeutic Implications

Understanding these axes transforms how we think about therapeutic technique. It’s not enough to have a bag of interventions; we need to understand which dimension of experience each intervention addresses and how to sequence them effectively.

Consider how this plays out clinically. A patient presents with anxiety. The fundamentalist Jungian might immediately go to dream work and archetypal amplification. The merger-with-psychoanalysis Jungian might focus exclusively on early attachment patterns. But dimensional thinking suggests we need to assess: Where is this person along each axis? Are they overidentified with thinking and cut off from feeling? Are they trapped in concrete worry (sensing) and unable to see broader patterns (intuition)? Is their executive control network hyperactive, suppressing default mode processing? Are they stuck in their heroic defenses, unable to access their inferior function’s wisdom?

The phased approach that emerges from this dimensional thinking looks like this:

Phase 1: Stabilization Through the Preferred Mode

Meet the patient where they are strong. If they’re a Thinker, engage their intellect first. If they’re a Senser, start with somatic interventions. This builds safety and alliance by validating their existing competence. This is where the patient’s “wants” are addressed.

Phase 2: Integration of the Underdeveloped Mode

Gradually introduce what’s missing. Help the Thinker feel. Help the Intuitive ground. Guide the person focused on external achievement toward inner life. Support the one lost in inner worlds to engage outer reality. This is where the patient’s “needs” are addressed, though it often feels threatening to their established identity.

Phase 3: Dynamic Balance

The goal isn’t to replace one mode with another but to develop flexibility, the ability to access different modes as situations require. This is what Jung called the transcendent function, the psyche’s capacity to hold opposites in creative tension.

Beyond Schools to Dimensions

What Samuels’ evolution reveals is that the schools themselves are attempts to emphasize different dimensional positions. The Classical school privileges the conscious-unconscious and personal-collective axes. The Developmental school focuses on early personal history and the thinking-feeling axis as it manifests in transference. The Archetypal school emphasized intuition and the collective unconscious.

The extremes Samuels identified (fundamentalism and merger) represent what happens when we lose dimensional flexibility. Fundamentalism rigidly maintains one position on every axis. Merger abandons distinctive positioning altogether. Health, whether for schools of thought or individual psyches, lies in maintaining dynamic tension, the ability to move along these dimensions as needed.

This dimensional model explains why the most creative analysts often worked at the boundaries between schools. When Marion Woodman brought the body (sensing) into archetypal psychology (intuition), she was building bridges along the sensing-intuition axis. When Michael Fordham integrated infant observation with archetypal theory, he was connecting the personal-collective axis in new ways. When Robert Johnson made complex Jungian ideas simple and accessible, he was translating between different positions on the thinking-feeling axis.

Even peripheral figures like J.B. Rhine and Eugene Osty, the parapsychologists Jung corresponded with, represent exploration of another axis: the empirical-numinous dimension. Their work reminds us that Jung himself was always trying to hold seemingly irreconcilable opposites, to find empirical approaches to the numinous, scientific methods for the soul.

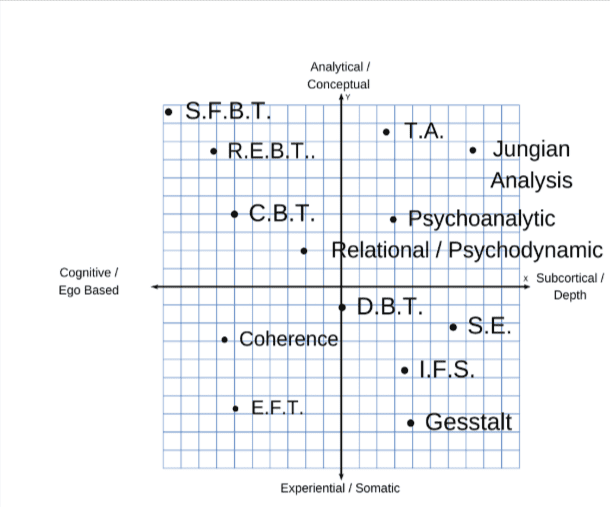

| SFBT – Solution Focused Brief Therapy(Steve de Shazer)

CBT – Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Aaron Beck) REBT – Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (Albert Ellis) TA – Transactional Analysis (Eric Berne) EFT – Emotion Focused Therapy (Sue Johnston) IFS – Internal Family Systems (Richard Schwartz) SE – Somatic Experiencing (Peter Levine) Gestalt – (Fritz Perls) Jungian Analysis – (Carl Jung) Psychodynamic / Psychoanalytic – (Sigmund Freud, Neo Freudians) |

The Living Matrix of Psychotherapy

The evolution of Samuels’ model from three discrete schools to four points on a spectrum, and finally to his recognition that all these schools exist within each analyst, parallels a broader evolution in how we understand psychotherapy itself. We’re moving from a model of competing schools to understanding therapy as navigation through a multidimensional space of human experience.

This doesn’t mean all approaches are equal or that anything goes. Different patients need different dimensional emphases at different times. The art lies in assessment: Where is this person in this multidimensional space? What dimensions are overdeveloped, serving as defensive fortresses? What dimensions are underdeveloped, containing both their suffering and their potential? How can we create a therapeutic process that honors their strengths while gradually expanding their range?

The diagram below illustrates these dimensional axes that every therapist and patient must navigate. No single school or approach can address all dimensions simultaneously. The clinical art lies in knowing which dimension needs attention when, and having the flexibility to shift our approach accordingly. As Samuels came to understand, we all contain multiple schools within us because human experience itself is irreducibly multidimensional. The question is not which school is right, but which dimensional emphasis serves this particular person at this particular moment in their journey toward wholeness.

0 Comments