A Deep Dive into Ego States, Games, and the Quest to Understand Human Behavior

In the 1960s, a charismatic psychiatrist named Eric Berne took the world of psychotherapy by storm with his innovative approach known as transactional analysis (TA). Combining elements of Freudian psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology, and the era’s fascination with game theory, Berne created a compelling model of the human psyche that captured the public’s imagination. His bestselling books, including “Games People Play,” propelled TA to dizzying heights of popularity. But as quickly as it rose, transactional analysis fell from grace, displaced by newer theories. Yet Berne’s concepts of ego states, games, and life scripts maintain an enduring influence on psychology.

In this comprehensive article, we’ll trace the meteoric rise and eventual decline of Berne’s transactional analysis. We’ll explore how Berne melded diverse influences into a powerful theory, break down key concepts like ego states and games, and examine TA’s lasting impact on psychotherapy. Strap in for an illuminating journey through one of psychology’s most influential and intriguing theories.

Eric Berne and the Birth of Transactional Analysis

Eric Berne (1910-1970) seemed destined to leave his mark on psychiatry. Born in Montreal to a physician father and writer mother, Berne excelled academically, earning an MD and psychiatric certification from McGill University. After a stint in the US Army Medical Corps during WWII, Berne settled in Carmel, California, where he honed his skills as a therapist and lecturer.

Berne was steeped in traditional psychoanalysis, having studied under Paul Federn, one of Freud’s colleagues. However, he grew dissatisfied with psychoanalysis’ long-winded and deterministic bent. Inspired by neo-Freudians like Erik Erikson and Harry Stack Sullivan who emphasized interpersonal factors and the social self, Berne began developing his own theory.

Transactional analysis crystallized in the late 1950s as Berne synthesized psychoanalytic concepts, humanistic ideas about free will and autonomy, and the postwar infatuation with cybernetics, systems theory, and game theory. The 1956 publication of “Transactional Analysis: A New and Effective Method of Group Therapy” in the American Journal of Psychotherapy marked the theory’s formal debut.

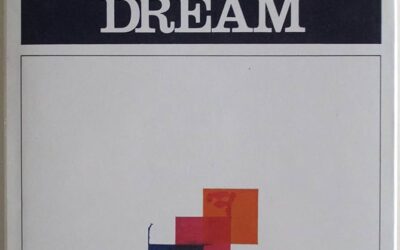

In 1958, Berne founded the Seminar in Transactional Analysis in San Francisco, attracting students and adherents like Claude Steiner and Thomas A. Harris. The burgeoning TA movement gained steam with the bestselling success of Berne’s “Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy” (1961) and pop psychology classic “Games People Play” (1964).

As Berne disseminated TA through his International Transactional Analysis Association (ITAA), founded in 1964, and conducted scores of seminars and training workshops, transactional analysis became the psychotherapy approach of the moment. The accessible nature of Berne’s ideas – distilled to punchy one-liners and compelling metaphors – resonated with the individualistic, self-improvement ethos of the 1960s.

The Foundations of TA: Ego States, Transactions, Strokes

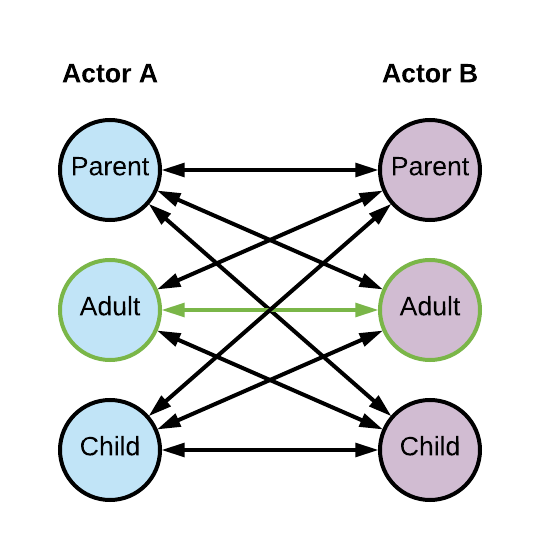

At the heart of transactional analysis lie three key concepts: ego states, transactions, and strokes. Ego states refer to the three different facets of the personality that shape our behavior and internal experiences. Berne named these the Parent, Adult, and Child ego states, each with distinct characteristics:

Parent:

The part of our personality that reflects the internalized attitudes, values, and behaviors of authority figures, particularly our parents. The Parent ego state can be nurturing or critical.

Adult:

The rational, objective part of the personality that processes information and makes decisions based on logic and reality-testing. The Adult mediates between the Parent and Child.

Child:

The childlike part of the personality that experiences emotions, creativity, spontaneity, and dependency needs. The Child can be free and natural or adapted based on parental/societal conditioning.

According to Berne, our ego states shape the nature of the “transactions” (communication/interactions) we have with others. He identified three main types of transactions:

Complementary:

Adult-Adult, Parent-Child, or Child-Parent transactions where the ego states align and communication flows smoothly.

Crossed:

Transactions where the ego states don’t match up, leading to misunderstandings and conflicts.

Ulterior:

Transactions with an overt social level and a covert psychological level conveying a hidden agenda. The covert level determines the outcome.

Berne also introduced the concept of “strokes,” the fundamental unit of social interaction. Strokes are moments of recognition and can be verbal/nonverbal, positive/negative, conditional/unconditional. Berne proposed the controversial idea that any stroke – even negative attention – is preferable to no strokes at all.

By analyzing the interplay of ego states and type of transactions in an interaction, TA practitioners aim to identify problematic patterns and help clients communicate from their Adult to improve relationships.

Games People Play

Berne’s most famous contribution to psychology was his theory of “games.” Games, in the TA framework, are series of ulterior transactions with a gimmick and payoff. They are ritualistic, repetitive, unconscious patterns people act out to obtain strokes, structure time, and reinforce beliefs rooted in childhood.

Games have strict rules and roles like Persecutor, Victim and Rescuer. Because they rely on crossed and ulterior transactions, games lead to predictable outcomes that leave players feeling frustrated or unsatisfied. Yet games also provide much-needed strokes and existential structure.

-

“Why Don’t You – Yes But”:

- Moves: Victim seeks advice from Rescuer, but finds excuses to reject each suggestion. Rescuer becomes increasingly frustrated until lashing out critically (switch to Persecutor).

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent), Persecutor (Critical Parent)

- Payoff: Victim obtains strokes for “trying” while confirming belief that change is impossible. Rescuer feels exasperated but morally superior.

-

“If It Weren’t For You”:

- Moves: Victim blames Persecutor for their problems and life constraints. Persecutor defends and counterattacks. Heated exchange ensues.

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Persecutor (Critical Parent)

- Payoff: Victim avoids responsibility and gets strokes for “suffering.” Persecutor feels superior and in control.

-

“See What You Made Me Do”:

- Moves: After a mishap, Victim blames Persecutor for “causing” it through some prior action. Persecutor protests innocence. Argument escalates.

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Persecutor (Critical Parent)

- Payoff: Victim dodges accountability and guilt. Persecutor feels unfairly attacked but righteously indignant.

- “Now I’ve Got

You, You Son of a Bitch”:

- Moves: Persecutor seizes on minor mistake by Victim as pretext for global character assassination. Victim becomes defensive, counterattacks.

- Roles: Persecutor (Critical Parent), Victim (Adapted Child)

- Payoff: Persecutor gets to act out sadistic impulses. Victim feels unjustly shamed but morally vindicated.

-

“Let’s You and Him Fight”:

- Moves: Persecutor subtly provokes a conflict between two Victims, often by spreading gossip or playing devil’s advocate. Persecutor eggs on combatants and enjoys the show.

- Roles: Persecutor (Critical Parent), Victims (Adapted Child)

- Payoff: Persecutor gets entertainment and feels superior. Victims vent anger but remain unaware of being played.

-

“Wooden Leg”:

- Moves: Victim uses a real or imagined disability as an excuse for not meeting responsibilities or pursuing change. Others initially express sympathy (Rescuer) but eventually feel resentful (Persecutor).

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent), Persecutor (Critical Parent)

- Payoff: Victim gains strokes for “suffering” and avoids expectations. Others feel guilty for their frustration.

-

“Schlemiel”:

- Moves: Victim engages in clumsy or inept behaviors that draw irritation from others (Persecutor). Victim apologizes profusely, often with charm and self-deprecating humor. Pattern repeats.

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Persecutor (Critical Parent)

- Payoff: Victim lowers expectations and responsibility. Persecutor feels superior but also guilty for anger.

-

“Poor Me”:

- Moves: Victim constantly bemoans their misfortunes and hardships. Rescuers offer support and advice, which Victim subtly rejects. Rescuers burn out and pull away (Victim switch).

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent), Victim (Adapted Child)

- Payoff: Victim gets strokes for martyrdom, avoids solving problems. Rescuers feel initially valued, then drained.

-

“Ain’t It Awful”:

- Moves: Victim laments a personal or societal problem. Rescuers join in bemoaning the issue and offering sympathy, but no one takes action. Gripe session continues.

- Roles: Victims (Adapted Child), Rescuers (Nurturing Parent)

- Payoff: Victims get strokes and camaraderie from shared misery. Everyone avoids responsibility for change.

-

“Kick Me”:

- Moves: Victim sets up situations or acts in ways to provoke criticism and rejection (Kick Me signs). Persecutors take the bait and “Kick”. Victim feels mistreated but self-righteously vindicated.

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Persecutor (Critical Parent)

- Payoff: Victim’s self-rejecting script beliefs are confirmed. Persecutor gets to act out cruel impulses.

-

“Blemish”:

- Moves: Rescuer offers Victim a positive stroke or opportunity. Victim finds a trivial fault (the Blemish) to discount the whole stroke. Rescuer feels unappreciated, resentful (Persecutor switch).

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent), Persecutor (Critical Parent)

- Payoff: Victim maintains a pessimistic worldview and avoids risk. Rescuer’s efforts are frustrated.

-

“Harried”:

- Moves: Victim constantly complains of being overloaded and behind schedule due to self-imposed demands. Rescuers offer practical help, which Victim declines. Frenzied activity continues.

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent)

- Payoff: Victim avoids intimacy and reflection. Rescuers feel inadequate and unappreciated.

-

“Stupid”:

- Moves: Victim deliberately bungles simple tasks. Rescuer takes over, feeling exasperated but morally obligated. Victim feigns appreciation but repeats “stupidity.”

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent)

- Payoff: Victim shirks responsibility and gets strokes for being “helpless”. Rescuer feels superior but resentful.

-

“Do Me Something”:

- Moves: Victim makes vague, open-ended demands of Rescuer. Rescuer tries to clarify and meet requests, but Victim finds fault with each attempt. Both end up frustrated.

- Roles: Victim (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent)

- Payoff: Victim gains attention, avoids responsibility. Rescuer feels valued initially, then inadequate and confused.

-

“Courtroom”:

- Moves: Victim or Persecutor (Prosecutor) accuses other of wrongdoing. Accused takes Defendant role. Both present evidence, testimonies to Rescuers (Judge, Jury). Argument escalates.

- Roles: Victim/Persecutor (Critical Parent), Victim/Persecutor (Adapted Child), Rescuer (Nurturing Parent)

- Payoff: Players experience drama and derive righteousness from roles. No one truly wins; players switch roles and repeat.

In each game, players take on scripted roles and engage in complementary and ulterior transactions that lead to a predictable, unsatisfying payoff. While players gain strokes and reinforce script beliefs, the rigid roles and dishonest communication prevent genuine problem-solving and intimacy.

By analyzing the moves, roles and payoffs of a client’s transactional patterns, TA therapists help bring games into Adult awareness. Clients can then learn to communicate needs and feelings directly, responding authentically instead of playing scripted roles. Developing game-free relationships is a key goal of TA therapy.

Life Scripts & Existential Positions

Berne expanded TA with his theory of “life scripts,” unconscious life plans formed in childhood based on parental programming and impactful decisions. Scripts are the self-reinforcing “stories of our lives” that determine the games we play, the paths we pursue, and the outcomes we expect.

Based on messages from Parent figures and the child’s decisions in response, Berne proposed three main categories of life scripts:

- Winner Scripts: Healthy, flexible, reality-based scripts leading to autonomy, productivity and intimacy. Winners approach life with an “I’m OK, You’re OK” attitude.

- Loser Scripts: Self-defeating, rigid scripts rooted in distorted childhood views that result in dysfunctional life paths, resentment and “I’m Not OK” positions.

- Non-Winner Scripts: Banal script paths of compliance and mediocrity that sacrifice autonomy for stability. Correspond to “I’m OK, You’re Not OK” and “I’m Not OK, You’re OK” positions.

These existential “OK positions” are the basic beliefs we hold about ourselves and others that influence our life choices. “I’m OK, You’re OK” reflects healthy self-esteem and acceptance. “I’m OK, You’re Not OK” suggests an inflated ego and disdain for others. “I’m Not OK, You’re OK” indicates low self-worth and idealization of others. “I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK” reflects a hopeless, nihilistic belief that life is pointless.

For Berne, the path to autonomy and self-actualization involves becoming script-free – making rational, Adult decisions in the here-and-now instead of compulsively playing out archaic losers scripts. TA therapists use techniques like “deconfusion,” regression analysis, game and script analysis to help clients develop the Adult ego state, challenge limiting scripts, and make new, autonomous choices.

Influences & Legacy

Berne masterfully synthesized concepts from psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology, behavioral/cognitive theories, communications theory, cybernetics and other contemporary influences into a cohesive, accessible framework. TA ideas parallel themes from Erikson, Adler, Jung, Rogers, Perls, Ellis, Harris, and Bateson, among others.

Despite TA’s popularity peak and decline, many core ideas – ego states, transactions, strokes, games, scripts – live on in modern approaches. TA laid foundations for:

-Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT):

Identifying self-defeating beliefs and behaviors, focus on present vs. past

-Schema therapy:

Early maladaptive schemas resemble Berne’s scripts

-Family systems therapy:

Communication patterns analyzed, games as dysfunctional roles

-Psychodrama/Gestalt:

Acting out roles and scripts, integrating fragmented self

-Integrative psychotherapy:

TA a longstanding influence on eclectic approaches

-Organizational psychology:

TA widely used for analyzing work dynamics and leadership styles

-Popular vernacular: Terms like “mind games,” “life scripts,” “inner child” have TA roots

Though some TA jargon and concepts seem dated today, Berne’s gift for distilling psychological insight into relatable, memorable ideas stands the test of time. TA reminds us that beneath outward appearances and social masks, people hunger for recognition, wrestle with self-limiting roles, and compulsively play out unconscious patterns – games – that prevent real intimacy. Berne shone a light on the hidden desires and existential dilemmas of being human in an often baffling social world.

Applying Ego State Theory in Therapy

Berne’s ego state model provides a powerful conceptual and pragmatic framework for psychotherapy:

Structural analysis:

Therapist assesses which ego states predominate in the client’s functioning. Contamination of Adult by critical Parent or anxious Child is a common problem. Goal is to strengthen Adult so it can effectively mediate between Parent and Child.

Transactional analysis proper:

Examining communication patterns to identify the ego states, transactions and games driving client’s interpersonal problems. Therapy aims to establish Adult-Adult relating.

Game analysis:

Helping clients recognize the ulterior transactions, roles and payoffs of their games. Therapist encourages “crossing the transaction” from Adult to break game pattern.

Script analysis:

Uncovering childhood experiences, injunctions and decisions fueling life script. Therapist helps client make new, autonomous decisions in the present. Regressing client to Child, reparenting by therapist’s nurturing Parent may aid this process.

Bibliography

Berne, E. (1961). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy: A systematic individual and social psychiatry.

Berne, E. (1964). Games people play: The psychology of human relationships.

Berne, E. (1972). What do you say after you say hello? The psychology of human destiny.

Harris, T. A. (1969). I’m OK, you’re OK. Harper & Row.

Steiner, C. M. (1974). Scripts people live: Transactional analysis of life scripts. Grove Press.

James, M., & Jongeward, D. (1971). Born to win: Transactional analysis with gestalt experiments. Addison-Wesley.

Karpman, S. (1968). Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin, 7(26), 39-43.

Dusay, J. M. (1972). Egograms and the constancy hypothesis. Transactional Analysis Journal, 2(3), 37-41.

Woollams, S. J., & Brown, M. (1979). Transactional analysis in brief. Huron Valley Institute Press.

0 Comments