The Silurian Hypothesis, proposed by astrophysicist Gavin Schmidt and astrobiologist Adam Frank in 2018, presents a fascinating question: if an advanced industrial civilization existed on Earth millions of years ago, would we even be able to detect it? Named after the fictional Silurians from Doctor Who, this scientific thought experiment challenges our assumptions about deep time, the permanence of civilizations, and the limits of human knowledge. While originally conceived as a tool for understanding how we might detect civilizations on other planets, the Silurian Hypothesis offers profound psychological and therapeutic insights about uncertainty, humility, and our relationship with the unknown.

As psychotherapists and individuals navigating an increasingly complex world, we often operate under the illusion that our current understanding of reality is complete and accurate. The Silurian Hypothesis disrupts this comfortable certainty by revealing the vast blindspots in our knowledge of Earth’s history and, by extension, in our understanding of ourselves and our place in the cosmos. This article explores how engaging with this hypothesis as a thought experiment can inform therapeutic practice, enhance cognitive flexibility, and provide a framework for working with uncertainty and existential anxiety.

The Science Behind the Blindspot

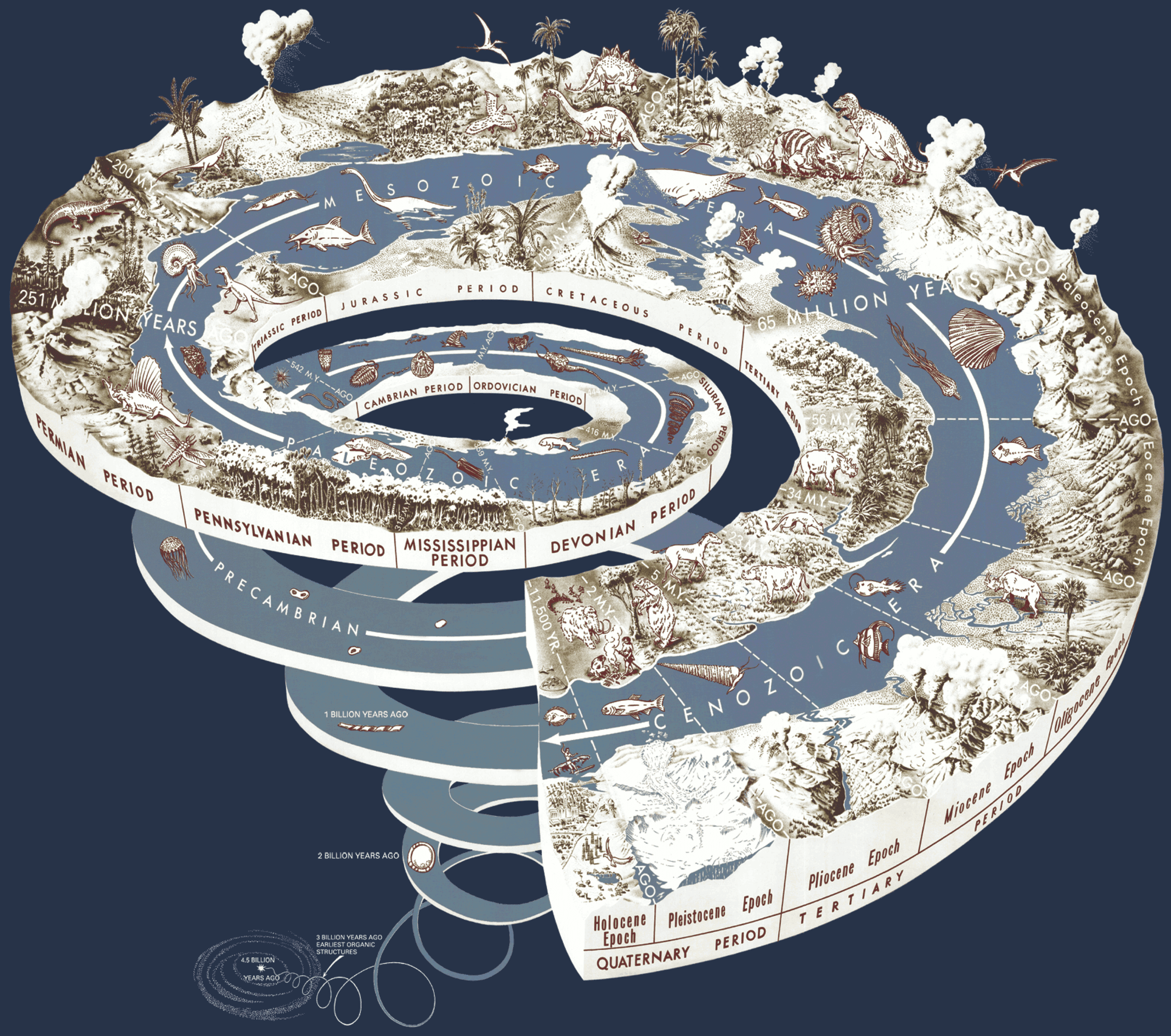

To understand the psychological implications of the Silurian Hypothesis, we must first grasp its scientific foundation. The Earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old, yet our archaeological record extends back only a few million years at most. Complex life has existed for over 500 million years, providing ample time for civilizations to rise and fall without leaving traces we could detect. The hypothesis rests on several key geological and archaeological realities that create massive blindspots in our understanding of deep history.

Tectonic activity continuously recycles the Earth’s crust through subduction, where oceanic plates slide beneath continental plates and melt back into the mantle. This process completely erases the geological record every 200-400 million years for oceanic crust. Even continental crust, which persists longer, undergoes constant erosion, metamorphosis, and burial. A city built 100 million years ago would have been subjected to forces that could grind it to dust, melt it down, or bury it beneath miles of sediment. The farther back we look, the less physical evidence remains.

Consider what archaeologists call the “taphonomic bias” – the systematic distortion in what gets preserved in the fossil and archaeological record. Only a tiny fraction of organisms become fossils, and an even smaller fraction of human-made objects survive more than a few thousand years. Plastic, often cited as humanity’s most enduring legacy, breaks down into microplastics within centuries and would likely be undetectable after millions of years. Even our most durable constructions – concrete buildings, stone monuments – would be ground to sand by geological processes operating over such timescales.

The temporal myopia inherent in archaeology becomes even more pronounced when we consider that modern humans have existed for only about 300,000 years, and industrial civilization for merely 300 years. If Earth’s history were compressed into a single year, our entire industrial age would occupy less than the last fraction of a second before midnight on December 31st. This perspective reveals how our assumption that we would “surely know” if advanced civilizations preceded us rests on a profound misunderstanding of deep time and geological processes.

The Isotopic Shadow: Reading Between the Lines

While direct archaeological evidence of ancient civilizations would likely be erased, the Silurian Hypothesis suggests we might detect indirect signatures through what researchers call the “Anthropocene fingerprint” – distinctive changes in isotope ratios and chemical compositions preserved in geological strata. Our current civilization is leaving such markers: altered carbon isotope ratios from fossil fuel burning, nitrogen isotope changes from industrial agriculture, and novel plutonium isotopes from nuclear testing.

However, detecting such signatures from a hypothetical ancient civilization presents enormous challenges. Many isotopic changes decay or become diluted over millions of years. The carbon spike from our fossil fuel use might appear in future geological records as a thin dark layer, easily missed or misinterpreted. Natural events like volcanic eruptions or asteroid impacts can produce similar signatures. The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, occurring 56 million years ago, shows a carbon isotope excursion remarkably similar to what an industrial civilization might produce, yet is generally attributed to natural causes.

This ambiguity in the geological record mirrors the ambiguities we face in psychotherapy when trying to reconstruct personal histories. Just as geological processes obscure and transform evidence of past events, psychological defenses, memory consolidation, and narrative reconstruction alter our access to our own histories. The therapeutic parallel is striking: we work with traces, shadows, and indirect evidence rather than clear, unambiguous records of what actually occurred.

Psychological Implications: Confronting Cosmic Humility

The Silurian Hypothesis serves as a powerful tool for what we might call “cognitive hygiene” – the practice of regularly examining and cleaning out our unexamined assumptions. When clients (or therapists) engage with this thought experiment, several therapeutic themes consistently emerge, each offering opportunities for psychological growth and increased mental flexibility.

First is the confrontation with epistemic humility – the recognition that there are fundamental limits to what we can know. This challenges the modern Western emphasis on knowledge acquisition and control. Many clients struggling with anxiety disorders exhibit a need for certainty and complete information before making decisions. The Silurian Hypothesis demonstrates that even in scientific domains, we must act and theorize based on incomplete information. This can be liberating for clients paralyzed by the need to “know for sure” before moving forward in their lives.

The hypothesis also evokes what we might term “temporal vertigo” – a dizzying recognition of the vastness of time and our infinitesimal place within it. While this can initially trigger existential anxiety, it can also provide perspective on personal problems. A client catastrophizing about a career setback might find relief in contemplating timescales where entire civilizations could rise and fall without a trace. This doesn’t minimize their experience but rather contextualizes it within a broader framework that can reduce the overwhelming urgency of immediate concerns.

Furthermore, engaging with the possibility of previous advanced civilizations challenges anthropocentric narcissism – the assumption that humans represent the pinnacle of evolution or that our civilization is unique in cosmic history. This decentering can be therapeutic for clients struggling with perfectionism or grandiosity, offering a more humble and connected view of human existence.

The Therapy of Uncertainty

In clinical practice, the Silurian Hypothesis can be introduced as a metaphorical framework for exploring how clients relate to uncertainty and the unknown. The hypothesis embodies what psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion called “negative capability” – the ability to remain in uncertainty and doubt without irritably reaching after fact and reason. This capacity is essential for psychological growth and creativity, yet our culture often pathologizes uncertainty as something to be eliminated rather than tolerated.

Consider how the hypothesis reframes our relationship with evidence and absence. In archaeology, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” – a principle equally applicable to psychotherapy. Clients often assume that because they cannot remember trauma, none occurred, or conversely, that vague feelings must indicate suppressed memories of specific events. The Silurian Hypothesis teaches us to hold multiple possibilities simultaneously without premature closure.

The thought experiment also illuminates how we construct narratives from limited data. Just as scientists must create coherent theories about Earth’s history from scattered geological evidence, we all construct life narratives from fragmentary memories and experiences. The hypothesis reveals how these narratives, while useful and necessary, are always provisional and subject to revision. This can help clients loosen rigid life stories that no longer serve them.

Working with the hypothesis in therapy might involve guided imagination exercises where clients envision discovering evidence of an ancient civilization, exploring what assumptions they would need to release and what new possibilities might emerge. This can serve as practice for releasing assumptions about their own lives and relationships, developing what we might call “psychological flexibility in deep time.”

Existential Themes: Mortality, Legacy, and Meaning

The Silurian Hypothesis profoundly engages with existential themes central to psychotherapy. The possibility that entire civilizations could vanish without a trace confronts us with ultimate mortality – not just personal death but the potential erasure of everything we consider permanent or significant. This “ontological humility” can paradoxically reduce death anxiety by normalizing impermanence at a cosmic scale.

The hypothesis also reframes questions of legacy and meaning. If our entire civilization might one day be undetectable, what constitutes meaningful action? This question, rather than leading to nihilism, often guides clients toward more immediate, relational, and present-focused values. The possibility of cosmic insignificance can liberate individuals from the burden of creating lasting monuments, redirecting attention to the quality of present-moment experience and relationships.

For clients struggling with environmental anxiety or climate grief, the Silurian Hypothesis offers a complex but potentially helpful perspective. While it doesn’t minimize current ecological crises, it suggests that Earth and life have endured and recovered from previous catastrophes. This deep-time perspective can transform paralyzing despair into what philosopher Joanna Macy calls “active hope” – engagement with current challenges without attachment to specific outcomes.

The hypothesis also speaks to what existential psychologists call “thrownness” – our condition of being thrust into existence without choosing the circumstances. Just as we cannot know what civilizations might have preceded us, we cannot fully understand the historical and cultural forces that shaped our present moment. This recognition can foster compassion for ourselves and others as we navigate existence with inherently limited understanding.

Collective Unconscious and Deep Time

From a Jungian perspective, the Silurian Hypothesis resonates with concepts of the collective unconscious and archetypal patterns that transcend individual experience. The possibility of previous civilizations suggests that patterns of rise and fall, creation and destruction, might be encoded not just in human psychology but in the deeper patterns of planetary existence.

The hypothesis invites speculation about what Jung might have called “planetary individuation” – the idea that Earth itself might undergo cycles of development, with civilizations serving as temporary expressions of consciousness emerging from matter. This framework can help clients understand their psychological processes as part of larger patterns extending beyond personal or even human scales.

Dreams and fantasies about lost civilizations, from Atlantis to science fiction scenarios, might reflect not just psychological projections but intuitions about the cyclical nature of consciousness and civilization. The Silurian Hypothesis gives scientific credibility to these mythological themes, validating the psyche’s engagement with deep time and cyclical history.

Working with these themes in therapy can help clients connect personal transformation with larger patterns of change and renewal. The death and rebirth of civilizations mirrors the psychological deaths and rebirths individuals experience through major life transitions, trauma recovery, and spiritual development.

Practical Applications in Therapeutic Practice

Integrating the Silurian Hypothesis into therapeutic practice requires sensitivity and skill. Not all clients will resonate with such abstract thought experiments, and timing is crucial. However, for clients who show interest in philosophical or scientific topics, the hypothesis can provide a rich framework for exploration.

One approach involves using the hypothesis as a projective tool, asking clients to imagine what traces they would want to leave if they knew their civilization would vanish. This can clarify values and priorities, distinguishing between ego-driven desires for permanence and deeper motivations for connection and contribution. The exercise often reveals that what clients most value – love, growth, experience – leaves no geological trace yet feels most meaningful.

For clients struggling with perfectionism or control issues, contemplating the limits of archaeological knowledge can be therapeutically useful. We might explore how they would function if they accepted that complete knowledge is impossible even in principle, not just in practice. This can lead to discussions about “good enough” decision-making and the courage required to act despite uncertainty.

The hypothesis also provides a framework for discussing intergenerational trauma and healing. Just as geological processes preserve some traces while erasing others, families and cultures selectively transmit certain experiences while others are lost or transformed. This can help clients understand that healing ancestral patterns doesn’t require perfect knowledge of what occurred, only attention to what persists in the present.

Group therapy settings might benefit from collective exploration of the hypothesis, using it to examine shared assumptions and build tolerance for diverse perspectives. The possibility that our entire worldview might be missing crucial information can foster intellectual humility and openness to others’ experiences and interpretations.

The Shadow of Progress: Questioning Linear Development

The Silurian Hypothesis challenges the narrative of linear progress that underlies much of modern thought, including many therapeutic modalities. If civilizations can rise and fall without a trace, progress is not inevitable but contingent and potentially reversible. This perspective can be therapeutic for clients who feel like failures for not maintaining linear life progress or who experience setbacks as catastrophic departures from expected trajectories.

The hypothesis suggests that development might be cyclical rather than linear, with periods of growth followed by dissolution and reformation. This aligns with many indigenous worldviews and Eastern philosophies that see time as cyclical rather than progressive. For clients from these cultural backgrounds, or those drawn to such perspectives, the Silurian Hypothesis provides scientific support for non-linear understandings of time and development.

This cyclical view can reframe depression, regression, and other “backward” movements as potentially necessary phases in larger patterns rather than simply pathological departures from healthy development. Just as civilizations might need to fall for new ones to emerge, psychological structures sometimes need to dissolve for growth to occur.

Integration, Ethics, and Responsibility

While the Silurian Hypothesis can expand perspective and reduce anxiety about control and permanence, it’s crucial to address potential misuse or misunderstanding. The possibility that civilizations disappear without a trace should not be used to justify nihilism or environmental destruction. Rather, it can deepen appreciation for the preciousness and fragility of our current moment.

Therapeutically, we must be careful not to use deep time perspectives to minimize or bypass legitimate present-moment suffering. The vastness of geological time doesn’t make current pain less real or important. Instead, the hypothesis can help clients hold both the ultimate impermanence of their troubles and their immediate validity and importance.

The ethical implications of the hypothesis extend to questions of therapeutic responsibility. If we acknowledge massive blindspots in our understanding of history and causation, we must also acknowledge limitations in our therapeutic theories and interventions. This can foster a more collaborative, experimental approach to therapy, where therapist and client jointly explore unknown territory rather than the therapist providing expert knowledge.

Embracing the Unknown

The Silurian Hypothesis ultimately invites us to develop a different relationship with the unknown – not as a problem to be solved but as a fundamental aspect of existence to be acknowledged and even embraced. For psychotherapy, this means recognizing that healing doesn’t require complete understanding of causes or guaranteed outcomes. Sometimes, the most therapeutic stance is to stand together at the edge of the known, gazing into mystery with curiosity rather than fear.

As we face collective challenges that seem unprecedented – climate change, technological disruption, social transformation – the Silurian Hypothesis reminds us that unprecedented changes have occurred before, possibly many times, without leaving clear records. This doesn’t diminish the importance of our current moment but rather connects us to larger patterns of transformation that extend beyond human memory or even geological evidence.

The hypothesis teaches us that absence of evidence for our deepest fears – or hopes – doesn’t mean they’re unfounded, just as the absence of evidence for ancient civilizations doesn’t prove they didn’t exist. In therapy, as in life, we must learn to navigate with incomplete maps, finding meaning and direction despite fundamental uncertainties about where we’ve been and where we’re going.

In embracing the Silurian Hypothesis as a therapeutic thought experiment, we join a lineage of thinkers who have used cosmic perspective to illuminate human psychology. From Plato’s cave to Pascal’s infinite spaces to Jung’s collective unconscious, philosophy and psychology have long recognized that contemplating the vast unknown can paradoxically help us better understand ourselves. The Silurian Hypothesis adds a modern, scientific dimension to this tradition, reminding us that even our most basic assumptions about history, progress, and knowledge rest on foundations far less solid than we might imagine – and that this uncertainty, rather than being a source of anxiety, can be a doorway to wisdom, humility, and growth.

Bibliography

Bion, Wilfred R. Attention and Interpretation: A Scientific Approach to Insight in Psycho-Analysis and Groups. London: Tavistock Publications, 1970.

Becker, Ernest. The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press, 1973.

Benner, Carrie. “Deep Time and the Self: Exploring Temporal Perspectives in Psychotherapy.” Journal of Contemplative Psychotherapy 15, no. 2 (2019): 45-62.

Bonneuil, Christophe and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us. London: Verso, 2016.

Brannen, Peter. The Ends of the World: Volcanic Apocalypses, Lethal Oceans, and Our Quest to Understand Earth’s Past Mass Extinctions. New York: Ecco, 2017.

Burke, Anthony, Stefanie Fishel, Audra Mitchell, Simon Dalby, and Daniel J. Levine. “Planet Politics: A Manifesto from the End of IR.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 44, no. 3 (2016): 499-523.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “The Climate of History: Four Theses.” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 2 (2009): 197-222.

Clark, Nigel. Inhuman Nature: Sociable Life on a Dynamic Planet. London: SAGE Publications, 2011.

Clark, Timothy. Ecocriticism on the Edge: The Anthropocene as a Threshold Concept. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Colebrook, Claire. Death of the PostHuman: Essays on Extinction, Vol. 1. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, 2014.

Connolly, William E. Facing the Planetary: Entangled Humanism and the Politics of Swarming. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Crutzen, Paul J. and Eugene F. Stoermer. “The ‘Anthropocene’.” Global Change Newsletter 41 (2000): 17-18.

Davies, Jeremy. The Birth of the Anthropocene. Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.

DeLanda, Manuel. A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. New York: Zone Books, 1997.

Dukes, Jeffrey S. “Burning Buried Sunshine: Human Consumption of Ancient Solar Energy.” Climatic Change 61, no. 1-2 (2003): 31-44.

Ellis, Erle C. Anthropocene: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Frank, Adam. Light of the Stars: Alien Worlds and the Fate of the Earth. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Frank, Adam and Gavin A. Schmidt. “The Silurian Hypothesis: Would It Be Possible to Detect an Industrial Civilization in the Geological Record?” Astrobiology 19, no. 9 (2019): 1162-1176.

Frankl, Viktor E. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

Gould, Stephen Jay. Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Grinspoon, David. Earth in Human Hands: Shaping Our Planet’s Future. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2016.

Grove, Jairus Victor. Savage Ecology: War and Geopolitics at the End of the World. Durham: Duke University Press, 2019.

Haff, Peter. “Humans and Technology in the Anthropocene: Six Rules.” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 2 (2014): 126-136.

Hamilton, Clive. Defiant Earth: The Fate of Humans in the Anthropocene. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper & Row, 1962.

Horn, Eva and Hannes Bergthaller. The Anthropocene: Key Issues for the Humanities. London: Routledge, 2019.

Jaspers, Karl. The Origin and Goal of History. Translated by Michael Bullock. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953.

Jung, Carl G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Edited by Aniela Jaffé. New York: Vintage Books, 1989.

Keats, John. The Complete Poetical Works and Letters of John Keats. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1899.

Klein, Naomi. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2014.

Latour, Bruno. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017.

Lewis, Simon L. and Mark A. Maslin. The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

Lifton, Robert Jay. The Climate Swerve: Reflections on Mind, Hope, and Survival. New York: The New Press, 2017.

Lorimer, Jamie. Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after Nature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Lovelock, James. The Revenge of Gaia: Earth’s Climate Crisis and the Fate of Humanity. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

Macy, Joanna and Chris Johnstone. Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2012.

Marshall, George. Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change. New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

May, Rollo. The Discovery of Being: Writings in Existential Psychology. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983.

McPhee, John. Annals of the Former World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

Mitchell, Audra. “Beyond Biodiversity and Species: Problematizing Extinction.” Theory, Culture & Society 33, no. 5 (2016): 23-42.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Morton, Timothy. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Norgaard, Kari Marie. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011.

Pascal, Blaise. Pensées. Translated by A.J. Krailsheimer. London: Penguin Books, 1995.

Pihkala, Panu. “Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety.” Sustainability 12, no. 19 (2020): 7836.

Purdy, Jedediah. After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Raworth, Kate. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017.

Richardson, Katherine. “Earth’s Boundaries?” Nature 461 (2009): 447-448.

Rockström, Johan and Mattias Klum. Big World, Small Planet: Abundance within Planetary Boundaries. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Rudwick, Martin J.S. Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Sagan, Carl. Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space. New York: Random House, 1994.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. Translated by Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library, 1956.

Schmidt, Gavin A. and Adam Frank. “The Silurian Hypothesis: How Do We Know We’re the Only Industrial Civilization on Earth?” NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies Publications (2018).

Scranton, Roy. Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2015.

Steffen, Will, Paul J. Crutzen, and John R. McNeill. “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?” AMBIO 36, no. 8 (2007): 614-621.

Stengers, Isabelle. In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, 2015.

Stolorow, Robert D. Trauma and Human Existence: Autobiographical, Psychoanalytic, and Philosophical Reflections. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Swimme, Brian and Thomas Berry. The Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1992.

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House, 2007.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Wachtel, Paul L. Cyclical Psychodynamics and the Contextual Self: The Inner World, the Intimate World, and the World of Culture and Society. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Wallace-Wells, David. The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2019.

Weintrobe, Sally, ed. Climate Psychology: Facing the Climate Crisis. London: Phoenix Publishing House, 2020.

Weisman, Alan. The World Without Us. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2007.

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Free Press, 1978.

Wilson, Edward O. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016.

Yalom, Irvin D. Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books, 1980.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Zalasiewicz, Jan. The Earth After Us: What Legacy Will Humans Leave in the Rocks? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Zalasiewicz, Jan, Mark Williams, and Colin N. Waters. “Can an Anthropocene Series Be Defined and Recognized?” Geological Society, London, Special Publications 395 (2014): 39-53.

0 Comments