Socrates and the Daimon: The Ancient Shamanic Function

Athens, 399 BCE. Socrates holds a cup of hemlock—poison that will kill him if he drinks it. His students beg him to flee; the guards would look the other way. He could escape to Thessaly and continue teaching. Instead, he drinks. Not because he’s suicidal or defeated, but to prove something that can’t be proven any other way: the daimon is real.

Athens, 399 BCE. Socrates holds a cup of hemlock—poison that will kill him if he drinks it. His students beg him to flee; the guards would look the other way. He could escape to Thessaly and continue teaching. Instead, he drinks. Not because he’s suicidal or defeated, but to prove something that can’t be proven any other way: the daimon is real.

The inner voice that had guided him all his life—the thing that tells him when he’s about to make a mistake, the thing that knows what his rational mind doesn’t—it’s not madness or delusion. It’s the most real thing there is. It’s what civilization must be built on, and what he’d made a career of passing on to the youth of Athens. It’s so real to him that he’ll die for it.

His last words: “I owe a cock to Asclepius, the god of healing”—because death is the cure, not for life, but for the illusion that we are only what we can measure, count, and define.

2,400 years later, we’re still arguing about what he died for. We just use different words now: the unconscious, intuition, implicit memory, predictive processing, the default mode network. But it’s the same thing. There’s something in us that knows, and everything depends on whether we will listen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3HaEue3W1sE

The Perennial Philosophy: What We Keep Forgetting

Here’s the thing about human nature: we keep discovering the same truths and forgetting them on purpose. Every culture finds shamans, every culture finds warriors. Every culture discovers that we’re multiple beings trying to coexist inside and outside our heads—in the individual and in society—and then every culture forgets.

As Aldous Huxley called it, this is the “perennial philosophy”—truths that keep showing up wearing different costumes:

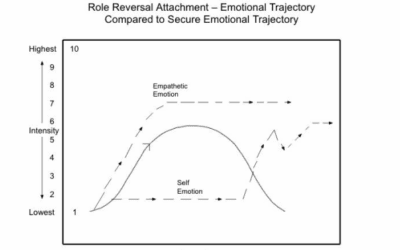

- We’re multiple, not singular: Plato believed in reason, spirit, and appetite—a tripartite soul. Freud had ego, superego, and id. Internal Family Systems has managers, firefighters, exiles, and Self. Neuroscience reveals multiple neural networks in constant negotiation.

- Healing happens through integration: You can’t kill your shadow. You can’t think your way out of trauma. You can’t medicate meaning—you medicate symptoms, and sometimes the symptom is there for a reason you need to examine.

- The body remembers everything: Ancient rituals, sacred dances, ritual movement. Reich had character armor. Modern trauma therapy rediscovers that the body keeps the score.

- Consciousness is bigger than the individual: Indigenous worldviews speak of being part of the web. Jung mapped the collective unconscious. Modern neurology shows mirror neurons, shared trauma, epigenetics, inherited family shadows.

Depression as Feature, Not Bug

Let’s talk about why depression, anxiety, dissociation, ADHD—even psychosis—might not be bugs in the code but features. Take sickle cell anemia: one copy of the gene gives you malaria resistance, two copies kills you. Evolution kept it around because in malaria zones, the trade-off was worth it.

Depression might be the same. Researchers like Paul Andrews and Jay Anderson Thompson argue that depression forces analytical thinking. When your ancestors faced complex social problems, the ones who could withdraw, ruminate, and problem-solve survived. The ones who stayed perpetually cheerful missed the danger signals—and they’re not your ancestors because they’re dead.

ADHD in a hunter-gatherer society? You want someone who notices everything, every moment, who can’t ignore stimuli, who’s always scanning for threats and opportunities. That’s not a disorder—that’s your scout, your early warning system.

Anxiety? That’s your risk assessor, the one who says “Maybe we shouldn’t eat those berries” or “That rustling might be a predator.” Without anxious people, the tribe dies of preventable disasters.

Psychosis? Every culture has people who hear voices, see visions, experience reality differently. We call them shamans, prophets, oracles. They heard patterns others couldn’t and brought back information from the edges of consciousness. They have a genetic predisposition for the brain’s indirect pathway—the mechanism that filters out information—to be wider open, so they’re hearing and seeing unconscious patterns others don’t perceive.

The problem isn’t that these traits exist. The problem is we built a world that doesn’t know what to do with them.

Warriors and Shamans: The Essential Dynamic

Here’s how it used to work: Every tribe needs warriors. They guard the boundaries of culture, maintain order, say “this is how we do things.” They’re inherently conservative because change might mean death to the system they protect.

Every tribe also needs shamans. They cross boundaries, go into darkness (literally or figuratively), bring back new information and possibilities. They say “What if we tried this?” They protect the future by guiding us toward what we could become.

Warriors without shamans become rigid, brittle, dead. Cultures of pure warriors don’t last—Athens was more flexible, victorious, and memorable than Sparta. Shamans without warriors become chaotic, groundless—they can go insane. A healthy tribe has both, and crucially, they need each other even when they drive each other crazy.

Sound familiar? It should. It’s the dynamic we’ve been tracking:

- Freud was a kind of warrior, Jung was a kind of shaman

- CBT is a warrior, depth psychology is shamanic

- Evidence-based practice represents the warrior paradigm, while somatic and mystical approaches are shamanic

The tragedy of modern psychology is that we let warriors win completely. We exiled the shamans, overidentified with ego, became an empire driven by profit motive. We became an overly objective, overly literal culture where the profit motive now controls science—and profit is inherently at odds with genuine scientific inquiry.

Now we’re a tribe with no one to hear the voices at the edge, no one who knows what to do with them, no one to dream new dreams, no one to say that depression might tell us something important.

The Metamodern Moment: Holding the Tension

What’s happening now, philosophically speaking, is what we call the metamodern period—after postmodernism, but because we’re in the middle of it, we don’t really know what it is. We’re oscillating between postmodern doubt about grand narratives (wanting to deconstruct everything) and the sincere belief and certainty of modernism’s vast movements and grand narratives.

This creates strange phenomena: an inability to analyze systems because two systems are happening at once, ironic detachment between individual and truth alongside radical sincere belief, heightened irony coexisting with distance from belief. This is Jung’s tension of opposites happening culturally, not just individually.

We need heroic narratives from modernism, but we also need to know they’re constructions (from postmodernism). We crave meaning and can’t turn that craving off, but we have to see through meanings. We want to believe but can’t unsee the machinery.

There’s a third way of knowing we must build—not a problem to be solved but an inevitable result of the last thousand years and increasingly rapid technological metaphors.

Multiple Memory Systems: Why Different Therapies Work

Modern neuroscience has discovered different types of memory, and trauma isn’t recorded like a videotape. There’s:

Explicit and declarative memory: What happened to me. CBT works here—these are things we’re conscious of, and therapy focusing on ego consciousness is good at treating them.

Implicit and procedural memory: What your body knows—how to ride a bike, how to dissociate. These are things you don’t think about.

Emotional memory: What you feel—your amygdala, preverbal memories, preconscious emotions. This is crucial for therapy and what CBT often misses because we feel emotions before thinking about them. By the time I’m thinking about it, the deep access is gone.

State-dependent memory: Things you know in certain states but not others. You need to prepare somebody—just because they’re not dissociating in the room doesn’t mean it’s not there.

Collective and transgenerational memories: Older than us, not something we have complete ownership of. Sometimes we need to feel our history, the journey of our people, our ancestors’ souls.

Different therapies work on different memory systems:

- DBT is great for relational trauma and emotional memory

- EMDR and brainspotting target acute flashback experiences

- Parts work addresses complex trauma by analyzing how different systems respond at different times

The real crime of the evidence-based practice paradigm was pretending there was one model that could do everything, that all therapy should be the same, that everyone got better the same way.

Alfred Adler’s Revolutionary Discovery

Cut back to Vienna, 1920. Alfred Adler walks past a church in his old neighborhood. Something’s wrong. As a child, he’d run past the cemetery by this church twice daily, heart pounding, certain death was chasing him. The graveyard had shaped his entire psychology—his theories about compensation, overcoming weakness through will.

But when he returns as an adult, there’s no cemetery. He asks locals, checks city records, examines maps going back a century. There never was a graveyard there, never had been. But the terror was real, the running was real. The cemetery was imagination—metaphor, a child’s mind creating concrete metaphor for abstract fear.

This separates Adler from both Freud and Jung: he realized our most formative memories might be complete fabrications. Not lies—metaphors. The psyche doesn’t record events; it records cosmology.

While Freud hunted for primal scenes and Jung mapped archetypes, Adler understood there’s no point analyzing what parents literally did because what you remember might never have happened, and what happened might be impossible to remember. Memories are emotional metaphors—stories the psyche tells itself about what it feels like to be alive.

Adler developed what actually works in therapy: not mystical depths or analytical dissection, but the human-to-human helping people rewrite their metaphors. Most techniques we associate with psychotherapy come from Alfred Adler, though he’s one of the least remembered:

- Relationships matter more than theory

- Encouragement beats interpretation

- Present choices matter more than past traumas

- You work with people, not on them

- Everyone’s trying to overcome something

These principles existed long before Carl Rogers and Virginia Satir, long before CBT claimed to have invented evidence-based techniques. Adler was doing them in 1910 without worksheets, without pretending the mind was a computer—just human to human.

Milton Erickson’s Intuitive Genius

Phoenix, 1970. Milton Erickson sits paralyzed from polio, colorblind, tone-deaf, in his wheelchair. He’s become the most influential therapist alive, and nobody can imitate him. Why? Because his technique was pure intuition, developed from a lifetime of being trapped in a body that didn’t work. He learned to read people like books.

A graduate student enters his office: “Dr. Erickson, I know you don’t like smoking, but I’ve taken up pipe smoking since enrolling in the program. I’ll smoke outside after we meet.”

Erickson doesn’t lecture about health. Instead, he describes the awkwardness of a friend who smoked a pipe—how if you blew down, you knew where it was going, but if you blew up, it was in your face. For 40 minutes, he drones on about the ritual of packing, tamping, lighting, relighting, storing, disassembling the pipe. How awkward these actions are, how they don’t really mean anything, how when you think about them, they’re not fun to do.

The student doesn’t realize he’s being hypnotized. Slowly, methodically, Erickson deconstructs every element—not attacking, just observing that they don’t have to be attached to a central narrative. The student realizes later he doesn’t actually like smoking; he liked the idea of smoking because he associated it with the serious scholar, with maturing into academia, with trying on a persona.

When he leaves and tries to light the pipe, he can’t do it anymore—but he’s still himself. By the next session, he can’t even put the pipe in his mouth. He’s thrown it out.

This is what Erickson understood: symptoms aren’t just problems—they’re blocked creative potential. They’re the psyche trying to grow but not knowing how, needing a bigger container, a bigger containing metaphor.

The Depressed Woman and the Colorful Bird

Erickson had a patient who said everything was gray, black and white, pointless. She’d seen all these therapists. Her husband wanted her to go on a trip, and it would be awful.

Erickson said: “Yes, your trip will be terrible. The airport will be gray, the flight miserable. Everything will be black and white like you’re describing—inconvenient, bleak, just as you expect. But that’s not where you’re going on this trip. You’re going to wait and wait and wait, and you will see one thing that is not black and white. You’re going to see one thing that is color.”

“How do you know?” she asked.

“I know. Come back and fire me. I’ll refund your money. You’re going to walk through every part of the trip seeing everything black and white, and then there will be one thing that is bright, vivid color, and it will possess you. That’s what the trip is for. Come back and let me know what you see.”

He didn’t know what she would see. He didn’t know she would see a bird, fall in love with ornithology, that it would define the rest of her life and pull her out of depression, giving her greater purpose. The color was a parrot, and it broke through her depression like lightning. She transformed her entire life.

Erickson didn’t prescribe birds—he prescribed looking. He gave her a bigger container for her experience even though he didn’t know what that container was. He could sit with the uncertainty of becoming big enough to contain her uncertainty.

What We Need Now: Bigger Containers

This is what we need in the metamodern moment: not smaller definitions, not tighter diagnostic categories, not more precise worksheets—bigger containers. Metaphors that can hold our expanding experience as individuals and as society.

We’re breaking out of old containers:

- Nation-states can’t contain global problems

- Individual therapy can’t contain systemic trauma

- Scientific materialism can’t contain consciousness

- Old stories can’t contain new realities

What we need is what Adler discovered: our memories are metaphors, so we can rewrite them. What Erickson knew: people aren’t broken, they’re stuck. They don’t need fixing; they need bigger stories.

But here’s the hard part: you can’t fake intuition. You can’t workshop your way to wisdom. You can’t pretend you’re Erickson if you haven’t done the work. The work is ongoing, but the central alchemy is this: separating your own intuition from your own trauma, because they come from the same part of the brain and feel the same.

When you’re in flow state, both can possess you in a way that feels authentic, because trauma feels like intuition—but it’s not. Trauma says danger is everywhere, you have to feel this emotion or can’t feel that one. Intuition says feel whatever you want, walk wherever you want—yes, there’s danger, but you’re still safe.

The Crisis and the Opportunity

If you’re in this field—student, therapist, human being trying to help—and everything looks gray, feels stupid and pointless, you’re probably right. The system is stupid, the worksheets are pointless. But like Erickson’s patient, you need to look for the bird—the thing in color, the self-evident truth that breaks through the gray and lets you help people and yourself.

Maybe it’s a client who transforms despite your terrible training. Maybe it’s a technique that works even though it shouldn’t. Maybe it’s realizing that what actually helps people has nothing to do with what you’re being taught. When you see it, trust it—even if you don’t understand it, especially if you don’t understand it, even if it scares you.

The baseline for real therapy is knowing that:

- Emotions are biophysiological processes

- Trauma lives in the body

- We’re naturally multiple—parts of self, parts of memory

- Integration is the goal

- Direct experience matters, not just logical understanding

- Mystery is real—you have to know you don’t know everything

The Return from Exile

Mental health is collapsing, warrior approaches are failing, and the shamans are returning from exile—not to take over but to restore balance. We need metamodern therapy that is evidence-based and mystery-friendly, scientifically rigorous and somatically wise, individually healing and systemically aware.

We need ancient wisdom and modern neuroscience, and we don’t need to mistake one for the other. We’re not picking sides—we’re holding tensions.

What actually works is being seen, being felt, being held, meaning-making, integrating parts, feeling feelings, moving trauma through the body, connecting to something bigger. This means we’re not just being analyzed or understood by the therapist. We’re going into the heart of it, not having meaning imposed, not killing “bad” parts of self, not just thinking but actually feeling, not just talking but experiencing, not just getting individual fixes but connecting to something larger.

The future of therapy isn’t new techniques—it’s remembering why we need shamans, and then those techniques will come. Things like brainspotting, QEEG brain mapping, polyvagal nerve stimulation, neuromodulation—innovations that use modern science to interact with ancient wisdom.

The Perennial Truth

People on the edges hear voices. The body does keep the score. There is a perennial philosophy that keeps coming back because it’s true—but not true like 2+2=4. True like the sun rises. True like children need love. True like we’re all going to die and have to deal with that, because that energy goes somewhere if we don’t.

It’s the kind of true you can’t prove—you only know it, live it, and pass it on to those ready to hear. The future of therapy is ancient. The healing we need is what we’ve always known. The truth that can’t be killed because it was never born, can’t be spoken because maybe it can’t be explained, can’t be taught because it can only be felt.

It just is—like the daimon, like the sunrise, like the voices at the edges calling all of us home.

Bibliography

- Adler, Alfred. The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology. Routledge, 1924.

- Andrews, Paul W. and J. Anderson Thompson. “The Bright Side of Being Blue: Depression as an Adaptation for Analyzing Complex Problems.” Psychological Review, 2009.

- Chaplin, Charlie. The Great Dictator. United Artists, 1940.

- Erickson, Milton H. The Collected Papers of Milton H. Erickson. Irvington Publishers, 1980.

- Freud, Sigmund. The Ego and the Id. W. W. Norton, 1923.

- Huxley, Aldous. The Perennial Philosophy. Harper & Brothers, 1945.

- Jung, Carl Gustav. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press, 1969.

- Lumet, Sidney. Network. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1976.

- Moore, Robert. The Archetype of Initiation. Xlibris, 2001.

- Plato. The Republic. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Oxford University Press, 380 BCE/1888.

- Rogers, Carl. On Becoming a Person. Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

- Satir, Virginia. Conjoint Family Therapy. Science and Behavior Books, 1964.

- Schwartz, Richard. Internal Family Systems Therapy. Guilford Press, 1995.

- van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score. Viking, 2014.

- Vermeulen, Timotheus and Robin van den Akker. “Notes on Metamodernism.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 2010.

0 Comments