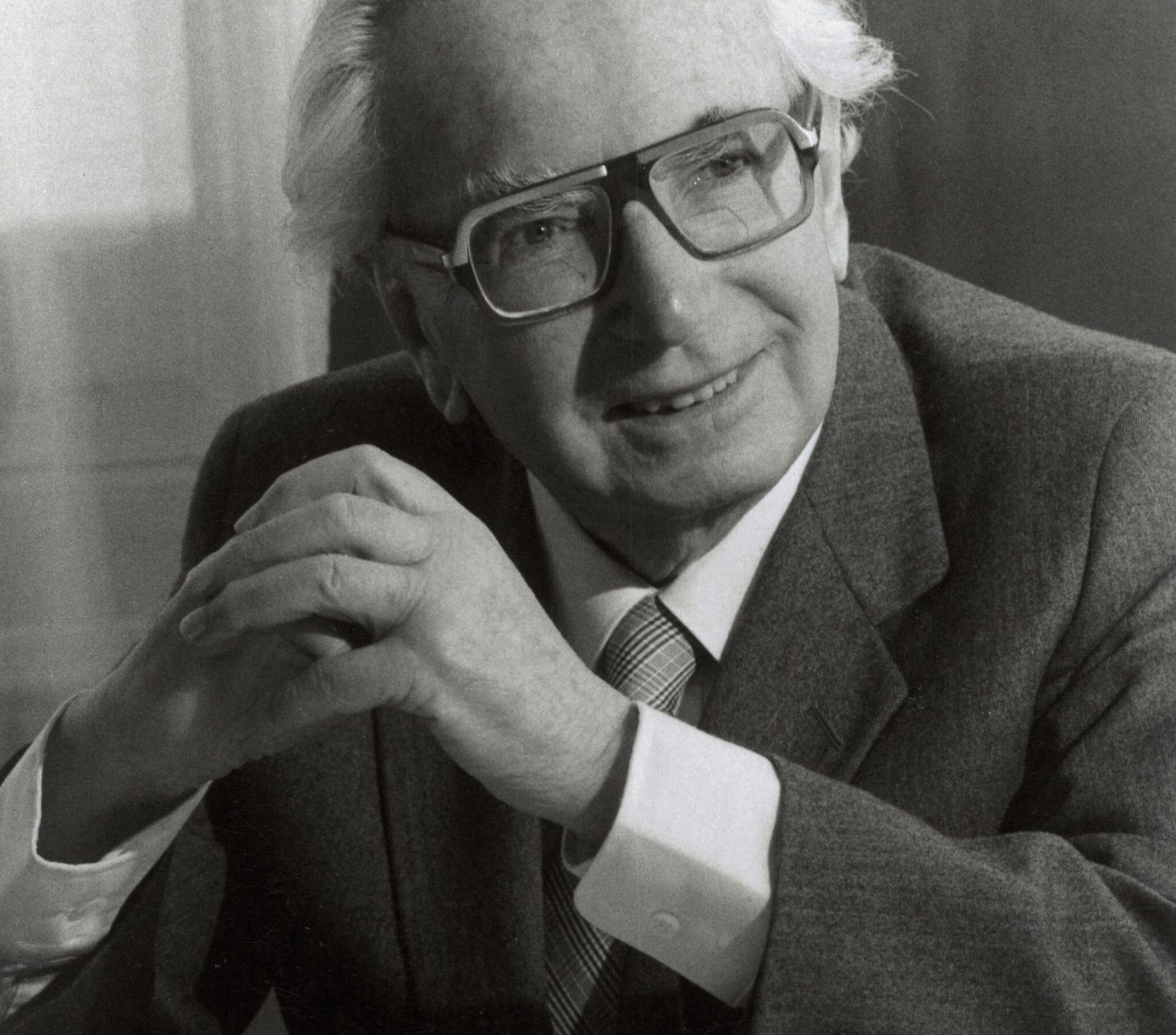

1. Who Was Viktor Frankl?

Viktor Emil Frankl (1905-1997) was a pioneering psychiatrist, neurologist, philosopher, and Holocaust survivor whose groundbreaking work transformed our understanding of human suffering, resilience, and the search for meaning. Born in Vienna, Austria, Frankl survived three years in Nazi concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Dachau, an experience that profoundly shaped his therapeutic approach and philosophical outlook. His innovative theories integrated existential philosophy, humanistic psychology, and his personal experiences to create logotherapy – often referred to as the “Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy” after Freud’s psychoanalysis and Adler’s individual psychology. Frankl’s seminal work, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” has sold millions of copies worldwide and continues to inspire readers with its profound message of hope and resilience. This article explores his key theories and their enduring relevance in psychology, philosophy, and everyday life.

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- Viktor Frankl developed logotherapy, a meaning-centered approach to psychotherapy that focuses on helping people discover purpose in their lives, even amid suffering and adversity.

- Central to Frankl’s work is the concept of the “will to meaning” – the fundamental human drive to find purpose and significance in life that transcends pleasure-seeking or power drives.

- Frankl proposed three primary pathways to discovering meaning: through creative work and achievements, through experiences and relationships, and through one’s attitude toward unavoidable suffering.

- Frankl’s concentration camp experiences revealed that those who maintained a sense of meaning and purpose showed greater resilience in the face of extreme suffering and dehumanization.

- The concept of “tragic optimism” in Frankl’s work suggests that one can remain optimistic even in the face of the “tragic triad” of pain, guilt, and death by transforming personal tragedy into triumph.

- Freedom of will is a cornerstone of logotherapy, emphasizing that while humans cannot control all circumstances, they retain the freedom to choose their attitude toward any situation.

- Frankl introduced the technique of “paradoxical intention,” which involves encouraging patients to intend or wish for the very thing they fear as a means of breaking cycles of anticipatory anxiety.

- The “existential vacuum” describes the state of meaninglessness and boredom that can lead to various psychological disturbances, including depression, addiction, and aggression.

- Frankl emphasized the importance of self-transcendence – reaching beyond oneself toward something greater – as essential for authentic human fulfillment.

- Logotherapy offers a framework for addressing modern challenges of nihilism, despair, and spiritual emptiness by reconnecting individuals with their core values and potential for meaning.

- Frankl’s work bridges psychology with philosophy, spirituality, and ethics, offering a holistic approach to human existence that honors both suffering and resilience.

- The humanistic perspective in Frankl’s theories provides a framework for understanding the spiritual dimension of the human person while respecting individual differences in how meaning is discovered and expressed.

2. The Will to Meaning and the Search for Purpose

Central to Frankl’s work was the concept of the “will to meaning” – what he identified as the primary motivational force in human beings. Unlike Freud’s “will to pleasure” or Adler’s “will to power,” Frankl proposed that our most basic striving is for meaning and purpose. The search for meaning is not a secondary rationalization of instinctual drives but represents a genuine and fundamental human need. When this drive is frustrated, Frankl argued, psychological distress and existential vacuum arise.

Drawing on his observations in concentration camps, Frankl noted that those who maintained a sense of purpose – whether through hope of reunion with loved ones, commitment to unfinished work, or faith in a higher power – were more likely to survive the brutal conditions. This meaning orientation provided a psychological anchor amid chaos and suffering, demonstrating that humans are meaning-seeking creatures even in the most extreme circumstances.

The will to meaning manifests in our innate desire to find significance in our experiences, to create something of value, and to connect with something larger than ourselves. Frankl saw this drive as universal yet highly individual in its expression – each person must discover their own unique meanings rather than having them prescribed by others. This personalized quest for meaning respects the dignity and freedom of the individual while acknowledging our shared human condition.

3. The Three Pathways to Meaning

3.1. Creative Values Frankl proposed three primary avenues through which humans can discover meaning. The first pathway involves creative values – the meanings we find through what we give to the world through our work, creative endeavors, and achievements. By contributing something of value – whether through our profession, artistic expression, inventions, or service to others – we fulfill our potential and connect with purpose beyond ourselves.

Creative values need not be grand or publicly recognized to provide meaning. A teacher shaping young minds, a craftsperson creating objects of beauty and utility, a parent nurturing a child – all involve bringing something worthwhile into the world. Frankl emphasized that the specific form of creative expression is less important than the attitude of responsibility with which one approaches their work. When we view our labor as a calling rather than merely a job, we tap into this dimension of meaning.

3.2. Experiential Values The second pathway to meaning comes through experiential values – the meanings we discover by taking in what the world offers through experiences, relationships, and encounters with beauty, truth, and goodness. By opening ourselves to love, aesthetic appreciation, intellectual discovery, and connection with nature, we receive meaning that enriches our lives.

Frankl placed particular emphasis on the meaning-giving power of love. In the concentration camps, he observed how the mental image of his beloved wife sustained him through brutal conditions. Love, he wrote, enables us to grasp the essential traits and core value of another person, perceiving their potential and unique significance. Through genuine encounter with others, we transcend our isolation and discover profound meaning.

3.3. Attitudinal Values The third and perhaps most radical pathway to meaning involves attitudinal values – the meanings we create through our stance toward unavoidable suffering. When faced with a fate that cannot be changed, Frankl argued, we still retain the freedom to choose our attitude toward that fate. By transforming tragedy into human achievement and suffering into meaningful sacrifice, we access a profound dimension of meaning even in the most difficult circumstances.

This capacity for meaning amid suffering forms the cornerstone of Frankl’s approach. In the concentration camps, he witnessed individuals who, despite starvation and torture, maintained their human dignity by choosing compassion over cruelty, forgiveness over bitterness, and hope over despair. This freedom of attitude, which cannot be taken away even in the most dehumanizing conditions, represents the ultimate expression of human spiritual freedom.

4. Meaning and Resilience in Extreme Suffering

4.1. The Concentration Camp Experience Frankl’s theories were forged in the crucible of his concentration camp experiences from 1942 to 1945. Arrested for being Jewish, he was deported to multiple camps, including Auschwitz and Dachau, where he endured starvation, forced labor, disease, and the constant threat of execution. During this time, he lost his pregnant wife, parents, and brother to the Holocaust – losses he would only confirm after liberation.

In the camps, Frankl observed that survival was not primarily determined by physical strength or privileged position but by psychological resilience rooted in meaning. Those who maintained hope for the future, who found purpose in helping fellow prisoners, or who connected with spiritual or intellectual values showed remarkable stamina amid suffering. Conversely, those who lost their sense of future meaning often quickly succumbed to disease or suicide.

Frankl himself survived partly by mentally reconstructing the manuscript of his first book on logotherapy, which had been confiscated upon his arrest. He would scribble notes on small scraps of paper and envision himself lecturing about his camp experiences in the future. This project gave him purpose beyond mere survival and helped him maintain his professional identity amid dehumanizing conditions.

4.2. Finding Meaning in Suffering From these observations emerged Frankl’s distinctive view of suffering. Unlike many psychological approaches that aim primarily to alleviate pain, logotherapy recognizes that suffering is an inevitable part of human existence that can potentially be meaningful. When suffering cannot be avoided, the question becomes not “Why is this happening to me?” but “What response is this calling forth from me?”

This reframing transforms the sufferer from passive victim to active responder. By choosing courage in the face of fear, dignity amid humiliation, or compassion amid cruelty, the individual actualizes attitudinal values that transcend their circumstances. Such suffering, Frankl argued, can become a kind of “existential achievement” that deepens one’s humanity and contributes to personal growth.

However, Frankl strongly emphasized that this view does not glorify suffering for its own sake. Unnecessary suffering should be alleviated whenever possible. Logotherapy aims to help people find meaning despite suffering, not because of it. The key distinction lies in the attitude one takes toward unavoidable pain – whether one surrenders to despair or transforms suffering into meaningful sacrifice.

5. Freedom, Responsibility, and Meaning

5.1. Freedom of Will A cornerstone of Frankl’s approach is the concept of freedom of will – the idea that humans, while subject to biological, psychological, and social conditions, always retain the freedom to take a stand toward these conditions. This freedom constitutes the spiritual dimension of humanity that transcends deterministic explanations.

The concentration camp experiences confirmed Frankl’s belief in this freedom. Despite brutal conditions designed to strip prisoners of all dignity and autonomy, he witnessed individuals who maintained their inner liberty – who chose to share their last piece of bread, offer words of encouragement, or face death with dignity. Such actions revealed that “the last of human freedoms” is the ability to choose one’s attitude in any given circumstance.

This freedom carries profound implications for psychological health. Rather than viewing humans as passive products of drives and conditioning, logotherapy sees each person as an active agent capable of self-determination. Therapy aims not to liberate people from their symptoms but to liberate their awareness of their responsibility to create a meaningful life despite limitations.

5.2. Responsibility as the Essence of Existence With freedom comes responsibility – not as a burden but as the very essence of human existence. Frankl often quoted Sartre’s statement that “man is condemned to be free,” but added his own perspective that “man is also condemned to be responsible.” Each moment presents choices about how to respond to life’s questions, and in these choices, we shape who we become.

Responsibility in logotherapy means “response-ability” – the ability to respond to the demands of life in a way that actualizes potential meanings. It involves asking not what we expect from life but what life expects from us. By shifting from a passive, entitlement-oriented stance to an active, responsive one, individuals discover their unique calling in each situation.

This responsibility extends beyond self to include others and the larger community. Frankl emphasized that meaning emerges not through self-actualization alone but through self-transcendence – reaching beyond oneself toward causes, relationships, and values that serve something greater. True fulfillment comes not from focusing on happiness as a goal but as a by-product of living responsibly.

6. Logotherapy: Theory and Practice

6.1. The Existential Vacuum Frankl identified a widespread condition in modern society that he termed the “existential vacuum” – a state of inner emptiness characterized by boredom, apathy, and a lack of meaning. This vacuum emerges when traditional values and structures that provided ready-made meanings break down, leaving individuals without clear direction or purpose.

The symptoms of existential vacuum include depression, aggression, addiction, and various forms of escapism. Unable to find authentic meaning, people may seek relief through pursuit of pleasure, accumulation of power, or conformity to mass movements. These substitutes for meaning provide temporary distraction but ultimately exacerbate the inner emptiness.

Frankl saw this vacuum as particularly prevalent in affluent societies where basic needs are met but existential needs remain unsatisfied. He noted that “Sunday neurosis” – the depression that settles in when the busy week ends and people confront their empty inner lives – reveals how material success alone cannot fulfill the human need for meaning.

6.2. Logotherapeutic Techniques To address the existential vacuum and other meaning-related struggles, Frankl developed several distinctive therapeutic techniques:

Paradoxical Intention involves encouraging patients to intend or even exaggerate the very thing they fear. A person with insomnia, for example, might be advised to try staying awake as long as possible rather than trying to fall asleep. This approach breaks the cycle of anticipatory anxiety and performance pressure that often maintains symptoms.

Dereflection redirects excessive self-focus toward meaningful activities and values beyond the self. Rather than obsessively monitoring symptoms or feelings, the patient is encouraged to engage with work, relationships, or causes that draw attention outward. This technique recognizes that happiness and well-being often arrive indirectly, as side effects of meaningful engagement.

Socratic Dialogue in logotherapy involves helping clients discover meanings already present but unrecognized in their lives. Through careful questioning, the therapist assists the person in uncovering their own values, potential purposes, and sources of meaning. This respects the uniqueness of each individual’s meaning-path while providing guidance in the discovery process.

Attitude Modification focuses on helping clients develop new perspectives toward unchangeable situations. When facing terminal illness, irreversible loss, or permanent disability, clients learn to activate their freedom of attitude – finding ways to live meaningfully despite, or even through, their limitations.

6.3. Applications Beyond Psychotherapy While developed as a therapeutic approach, logotherapy’s principles extend beyond clinical settings to education, business, community work, and personal development. Frankl envisioned his approach not merely as a treatment for pathology but as a philosophy of life applicable to all humans seeking meaning.

In education, logotherapy inspires meaning-centered approaches that help students connect with values and purposes beyond academic achievement. Teachers can serve as meaning-facilitators who help young people discover their unique contributions and callings.

In business and organizational settings, logotherapy offers frameworks for creating meaningful work environments that engage employees’ drive for purpose, not just productivity. Leaders who connect organizational goals to larger values foster greater commitment and satisfaction.

In community work and social services, logotherapy provides a dignifying approach that respects each person’s capacity for meaning and responsibility, even amid severe challenges. Rather than treating people as passive recipients of help, this approach empowers them as active creators of meaningful lives.

7. Tragic Optimism and the Defiant Human Spirit

7.1. The Concept of Tragic Optimism One of Frankl’s most powerful contributions is the concept of “tragic optimism” – the ability to remain optimistic and find meaning despite the “tragic triad” of pain, guilt, and death that inevitably touches all human lives. Rather than denying these realities or being crushed by them, the tragically optimistic person transforms potential tragedies into human achievement.

This approach differs fundamentally from naive positivity or toxic optimism that dismisses suffering. Instead, it acknowledges the full weight of human tragedy while affirming our capacity to respond meaningfully. It recognizes that life’s meaning is unconditional – circumstances may be terrible, yet the possibility of meaningful response remains.

Frankl illustrated this concept through countless examples from the concentration camps and his clinical practice. A grieving parent who channels loss into helping other bereaved families, a person with terminal illness who focuses on deepening relationships in their remaining time, a former offender who uses their experience to mentor at-risk youth – all demonstrate the human capacity to wrest meaning from tragedy.

7.2. The Defiant Power of the Human Spirit Underlying tragic optimism is what Frankl called “the defiant power of the human spirit” – the capacity to stand against psychological, biological, and social determinism to maintain one’s essential humanity. This spiritual dimension transcends both instinct and environment, allowing humans to choose values and meanings beyond conditioning.

This defiance manifests in our ability to:

- Rise above biological limitations (as when physically ill people maintain psychological well-being)

- Oppose psychological determinism (as when people act against their own temperamental inclinations out of commitment to values)

- Resist social pressures (as when individuals stand for principles despite social rejection)

- Find humor and perspective even in dire circumstances

The defiant human spirit represents the essence of human dignity – the unconditional value that remains even when all external markers of worth are stripped away. In the concentration camps, Frankl observed this spirit in prisoners who, despite starvation and abuse, shared their last piece of bread or spoke words of encouragement to fellow sufferers. Such actions transcended mere survival instinct, revealing humanity’s spiritual core.

8. Self-Transcendence and the Meaning of Love

8.1. Beyond Self-Actualization Frankl distinguished his approach from other humanistic psychologies by emphasizing that human fulfillment comes not primarily through self-actualization but through self-transcendence – reaching beyond oneself toward meanings, values, and people outside the self. “The more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself.”

This perspective challenged both the pleasure principle of Freud and the power principle of Adler, as well as some interpretations of Maslow’s hierarchy that place self-actualization as the highest human need. For Frankl, focusing directly on self-fulfillment paradoxically leads away from fulfillment; it is only by forgetting oneself in service to something greater that one becomes fully human.

Self-transcendence manifests in three primary dimensions:

- Vertical transcendence – reaching toward ultimate concerns, whether conceived as God, the cosmos, or transcendent values

- Horizontal transcendence – extending oneself toward others through love, service, and community

- Temporal transcendence – connecting with meanings that extend beyond one’s own lifetime through legacy and contribution

These dimensions interact and overlap, creating a rich landscape of potential meanings that draw the individual beyond self-concern toward greater participation in life’s fullness.

8.2. Love as Ultimate Meaning Among the forms of self-transcendence, Frankl gave special attention to love – the capacity to grasp another person in their uniqueness and potentiality. Through love, we glimpse the essential core of another being, seeing not just who they are but who they might become. This perception affirms the beloved’s unconditional value and dignity.

Frankl’s own experience illustrated this power. In the concentration camps, his mental conversations with his wife (whom he did not know had already been killed) sustained him through brutal conditions. The reality of their love transcended their physical separation, providing meaning that enabled survival. “Set me like a seal upon thy heart, love is as strong as death,” he quoted from the Song of Songs.

This view of love extends beyond romantic relationships to encompass all forms of genuine human connection. The therapist who perceives a patient’s potential beneath their pathology, the teacher who glimpses a student’s capacities beyond current performance, the friend who stands with another through suffering – all practice this meaning-giving love that affirms unconditional worth.

9. Meaning-Centered Education and Cultural Renewal

9.1. Educating for Meaning and Responsibility Frankl believed that education should focus not merely on transmitting knowledge or developing skills but on nurturing the capacity for meaning-finding and responsibility. In an age of increasing specialization and technological advancement, he argued, we must counterbalance technical training with humanistic education that addresses existential questions.

A meaning-centered education involves:

- Helping students discover their unique callings and contributions

- Developing the capacity for value-perception and ethical discernment

- Fostering responsibility toward self, others, and the larger community

- Cultivating the freedom of attitude even amid limitations and constraints

- Preparing young people to navigate an uncertain future with resilience

Teachers in this model serve not only as instructors but as exemplars who demonstrate meaning-oriented living through their own authentic engagement. They create spaces for students to wrestle with existential questions and discover personal answers rather than imposing predetermined meanings.

9.2. Cultural Healing in an Age of Meaninglessness Beyond individual therapy and education, Frankl envisioned logotherapy as offering resources for cultural healing. He diagnosed modern society as suffering from collective meaninglessness manifested in rising rates of depression, addiction, aggression, and suicide. The “mass neurotic triad” of depression, addiction, and aggression, he argued, stems largely from the existential vacuum.

To address this cultural crisis, Frankl proposed several key interventions:

- Revitalizing education to focus on values and meaning alongside technical training

- Creating community structures that foster genuine connection and shared purpose

- Developing cultural narratives that affirm human dignity and responsibility

- Encouraging each person to discover their unique contribution to the whole

- Maintaining space for transcendent values and spiritual questions in public discourse

Rather than imposing a single meaning system, this cultural renewal would create conditions where individuals can discover diverse yet authentic meanings. It would balance respect for pluralism with affirmation of certain universal human values – dignity, responsibility, and the capacity for meaningful choice.

10. The Spiritual Dimension of the Human Person

10.1. The Noetic Dimension Frankl distinguished three dimensions of human existence: the somatic (physical), the psychic (psychological), and the noetic (spiritual or noological). This third dimension – from the Greek “nous” meaning mind or spirit – represents the specifically human capacity for self-transcendence, value-perception, and meaning-orientation.

The noetic dimension is not identical with religious belief but encompasses all specifically human capabilities – ethical discernment, aesthetic appreciation, humor, creativity, love, and conscience. It represents the “specifically human” aspects of existence that transcend biological drives and psychological conditioning. Even atheists, Frankl noted, operate within this noetic dimension when they commit to values beyond themselves.

This dimensional ontology avoids both biological reductionism and spiritual dualism. Humans are unities-in-diversity, with physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects forming an integrated whole. Illness or disturbance in one dimension affects the others, requiring a holistic approach to healing that addresses all levels of being.

10.2. Spirituality and Religion in Logotherapy While maintaining a perspective that could embrace both religious and non-religious worldviews, Frankl acknowledged the significant role that religious faith plays in many people’s search for meaning. Religious beliefs provide ready frameworks of meaning, ethical guidance, and connection to transcendent reality that can sustain people through suffering.

Frankl described the relationship between logotherapy and religion using a geometric metaphor: just as an eye physician doesn’t tell patients what to see but helps them see clearly, logotherapy doesn’t prescribe specific meanings but helps people perceive the meanings already present in their lives. For many, these meanings include religious dimensions that logotherapy neither imposes nor excludes.

This approach respects religious diversity while recognizing common human needs for meaning, purpose, and transcendence. It allows religious meanings to be integrated into therapeutic work without requiring either therapist or client to share specific religious beliefs. What matters is not the particular content of one’s meaning system but its authenticity and capacity to inspire responsible living.

11. Logotherapy in a Global Context

11.1. Cross-Cultural Applications Frankl’s ideas have shown remarkable cross-cultural resonance, with logotherapy centers established across Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa. This global spread reflects the universal nature of the meaning question that transcends cultural boundaries while taking diverse forms in different contexts.

In collectivist cultures, logotherapy’s emphasis on self-transcendence and responsibility toward others aligns with traditional values of community and interpersonal harmony. In individualistic societies, it offers a corrective to excessive self-focus by reconnecting personal fulfillment with contribution to larger purposes.

In secularized Western contexts, logotherapy provides a framework for discussing existential and spiritual questions without requiring specific religious commitments. In more traditionally religious societies, it offers a bridge between psychological health and spiritual values, complementing faith-based approaches with psychological insights.

11.2. Addressing Global Challenges Frankl’s vision extends beyond individual therapy to addressing collective challenges of the 21st century. The search for meaning becomes particularly vital amid global crises that threaten to overwhelm with complexity and tragedy:

- Climate change and environmental degradation call for meaning-perspectives that connect personal choices with planetary wellbeing

- Technological disruption requires meaning frameworks to guide innovation toward human flourishing

- Cultural clashes and political polarization need meaning-oriented dialogue that respects diversity while seeking common ground

- Economic inequality demands meaning-centered approaches to work and wealth that prioritize human dignity over mere profit

In each of these domains, logotherapy offers resources for transforming potential despair into meaningful action. By emphasizing both freedom and responsibility, it helps individuals and communities respond to global challenges without either passive resignation or entitled expectations.

12. Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

12.1. Influence on Psychology and Psychotherapy Frankl’s work has profoundly influenced multiple fields, particularly the development of humanistic and existential therapies. His emphasis on meaning anticipated key themes in positive psychology, narrative therapy, and posttraumatic growth research. Concepts like “learned helplessness” and “resilience” echo Frankl’s observations about freedom of attitude amid suffering.

Contemporary therapeutic approaches incorporating logotherapy principles include:

- Meaning-Centered Counseling and Therapy, which directly applies logotherapeutic concepts in diverse clinical contexts

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which shares logotherapy’s emphasis on values-based living and psychological flexibility

- Narrative Therapy, which parallels logotherapy’s focus on constructing meaningful life-stories amid challenges

- Posttraumatic Growth models, which build on Frankl’s insights about finding meaning through suffering

Research increasingly confirms Frankl’s thesis that meaning-orientation correlates with psychological well-being, resilience, and life satisfaction. Studies show that people with a strong sense of purpose demonstrate better mental health outcomes, healthier behaviors, and even longer lives – empirical validation of Frankl’s clinical observations.

12.2. Philosophical and Spiritual Impact Beyond clinical psychology, Frankl’s ideas have influenced philosophy, theology, education, and business. His work bridges existential philosophy with practical psychology, offering concrete approaches to abstract questions of meaning and purpose. Theologians and spiritual leaders have found in logotherapy a framework compatible with diverse faith traditions yet accessible to secular audiences.

In an age characterized by what philosopher Charles Taylor calls “the malaise of modernity” – the emptiness and fragmentation that often accompanies technological advancement and traditional value-erosion – Frankl’s emphasis on meaning provides a vital counterbalance. Neither reactionary nor dismissive of modern challenges, logotherapy offers a middle path that honors both traditional wisdom and contemporary realities.

12.3. Frankl for the 21st Century As we navigate the complexity of the 21st century, Frankl’s insights remain remarkably relevant. In a world of increasing automation, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality, his emphasis on specifically human capabilities – meaning-perception, ethical choice, and spiritual sensibility – helps us distinguish what truly matters from what merely distracts.

In an era of information overload and constant stimulation, logotherapy reminds us that the key existential questions remain unchanged: What is my unique contribution? Whom and what do I love? How will I respond to suffering? These meaning-questions cut through the noise of modern life to what is essential and enduring.

For individuals facing uncertainty, loneliness, or existential anxiety, Frankl’s message offers both challenge and hope. By affirming our capacity for meaningful response even amid limitation, his approach replaces victimhood with responsibility and despair with “tragic optimism.” This stance – neither naive positivity nor cynical resignation – provides a sustainable orientation toward life’s complexities.

13. Conclusion: The Unconditional Meaning of Life

The legacy of Viktor Frankl offers a profound affirmation of human dignity and potential amid the most challenging circumstances. Through his own lived experience of extreme suffering and his clinical work with diverse populations, Frankl demonstrated that meaning remains possible in any situation, regardless of external conditions. This unconditional meaning of life stands as his most radical and hopeful contribution.

At the heart of Frankl’s vision is a fundamental choice that faces each person: to live as a passive victim of circumstance or as an active responder to life’s questions. Even in situations where external freedom is severely limited, he insisted, we retain the freedom to choose our attitude – to determine who we will become in relation to our conditions. This spiritual freedom constitutes the essence of human dignity that cannot be taken away by any external force.

For contemporary society facing multiple crises – ecological, technological, social, and existential – Frankl’s message provides both challenge and hope. He challenges us to move beyond the pursuit of power, pleasure, or comfort as ultimate goals, redirecting our attention to the meaning-possibilities present in each situation. Yet he offers hope by affirming our capacity to transform even suffering into meaningful achievement through the attitude we adopt toward it.

Perhaps most importantly, Frankl’s approach transcends the false dichotomy between individual fulfillment and social responsibility. Through the concept of self-transcendence, he shows that genuine personal meaning emerges precisely through connection with others, commitment to values, and contribution to purposes beyond ourselves. The search for meaning leads not to isolation but to deeper engagement with the community of beings of which we are part.

As we continue to wrestle with the great questions of human existence in an increasingly complex world, Frankl’s legacy invites us to cultivate both courage and compassion – the courage to face life’s challenges without evasion and the compassion to stand with others in their suffering. It reminds us that amid all technological advances and cultural changes, the essentially human task remains the same: to respond to life’s questions with the best answer we can give – the answer of our whole being.

In Frankl’s own words: “Live as if you were living for the second time and had acted as wrongly the first time as you are about to act now.” This imaginative exercise invites us to take full responsibility for our choices, recognizing their significance in the larger tapestry of meaning. By embracing this responsibility with both sobriety and hope, we honor the legacy of a man who knew firsthand that meaning can emerge even from the darkest experiences of human history.

0 Comments