Why Does Psychology Ignore Philosophy and Anthropology?

Time moves in one direction, memory in another.<br> We are that strange species that constructs artifacts intended to counter the natural flow of forgetting.

– William Gibson, “Dead Man Sings”

Psychology, as the scientific study of the mind and behavior, has made tremendous strides in understanding the human experience. However, two other disciplines – anthropology and philosophy – offer profound insights that can enrich and expand psychological perspectives. By drawing upon the wisdom of these fields, psychology can develop a more holistic, contextual, and meaning-centered approach to the complexities of mental life.

This article explores 21 key areas where anthropological and philosophical ideas can transform psychology, from rethinking the nature of selfhood and intersubjectivity to engaging with the farthest reaches of human consciousness. Along the way, we touch on thinkers as diverse as Merleau-Ponty, Hillman, Fanon, and Schopenhauer, while linking their insights to cutting edge research in embodied cognition, cultural neuroscience, and contemplative science.

The central argument is that psychology needs to move beyond its often unexamined assumptions about the mind as a natural, individual, internal entity. Instead, we must grapple with how the psyche is profoundly shaped by bodily, cultural, relational, and existential contexts. By dialoguing with anthropology and philosophy, psychology can expand its understanding of the human condition and imagines new possibilities for healing and flourishing.

1. Situating the Mind in Culture and Context

One of anthropology’s core insights is that human experience is profoundly shaped by cultural context. From David Abram’s work on how language and perception are interwoven with the natural world, to Victor Turner’s exploration of how ritual and symbolism structure social life, anthropologists emphasize the embeddedness of psychological processes in larger meaning systems.

This offers a crucial corrective to psychology’s tendency towards universalism and individualism. Rather than seeing the mind as an abstract, isolated entity, anthropology invites us to consider how mental phenomena are expressions of particular cultural worldviews, values, and practices. Symptoms of distress that appear pathological from one cultural lens may be adaptive or even sacred in another.

2. Attending to Embodied and Enacted Mind

Both phenomenological philosophy and anthropology of embodiment challenge psychology’s Cartesian legacy of seeing mind and body as separate. Maurice Merleau-Ponty argued that perception is an embodied process – we don’t passively observe the world, but actively engage with it through our senses and movements. Likewise, anthropologists like David Abram emphasize how cognition is distributed across brain, body and environment.

This shift towards an embodied, enactive view of mind has crucial implications for psychology. It suggests that we need to attend more closely to the bodily, sensorimotor dimensions of experience, emotion and thought. Practices like yoga, dance, martial arts and embodied mindfulness offer powerful ways of working with psychological distress that complement talk therapy. An embodied approach reminds us that healing often involves reintegrating and enlivening our felt sense of being, not just changing our thoughts.

3. The Narrative Nature of Selfhood

Philosophy and anthropology also converge in emphasizing the narrative, historically constructed nature of selfhood. Thinkers like Paul Ricoeur and Jerome Bruner argue that personal identity is not a fixed essence, but an ongoing story we tell about our lives, one shaped by the cultural plot lines and metaphors available to us. Anthropologists explore how different cultures offer different narrative templates for what a self can or should be.

For psychology, this underscores the therapeutic power of helping people re-author their life stories. When we can locate our suffering within a larger meaningful narrative, we become active meaning-makers, not just passive victims of circumstance. Narrative therapy, pioneered by Michael White and David Epston, operationalizes these insights, helping people identify and challenge the oppressive stories they’ve internalized so they can live into preferred versions of their lives.

4. Myth, Metaphor and the Poetic Basis of Mind

Depth psychologists like Freud and Jung argued that beneath the rational ego lies a rhizomatic underworld of images, impulses and emotions. Anthropology and philosophy deepen this recognition of the poetic, mythic basis of psyche. Ernst Cassirer saw humans as fundamentally “symbolic animals,” crafting worlds of meaning through myth, metaphor, art and ritual. Gaston Bachelard explored how poetic images reveal the “muscular unconscious,” the affective, imaginative dimension of embodied experience.

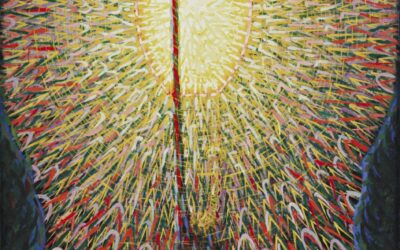

These thinkers challenge psychology to take seriously the imaginal, aesthetic dimensions of mind. They suggest that psychological healing must involve the body and imagination, not just the intellect. Working with dreams, fantasies, and poetic images – through methods like active imagination, arts therapy, or dreamwork – can help people access and integrate marginalized parts of their psyche. By engaging the mythopoetic mind, we open to deeper currents of meaning and regeneration.

5. Psyche as Dialogue and Polyphony

Another key theme in philosophy and anthropology is the intersubjective, dialogical nature of selfhood. Martin Buber argued that the I-Thou encounter is the basis of authentic relation, while Mikhail Bakhtin saw the psyche as polyphonic, a chorus of inner voices in constant conversation. Anthropologists likewise emphasize how identities emerge through social interaction and positioning.

For psychology, this suggests the need for a more relational, dialogical approach. Rather than seeing the self as unitary and autonomous, we can recognize how it emerges through the interplay of various sub-personalities, voices, and relational dynamics. Therapeutic approaches like Voice Dialogue, Internal Family Systems, and Psychosynthesis work with this inner multiplicity, helping people identify and integrate different parts of themselves. The goal is not to eliminate conflict, but to foster a richer, more textured inner conversation.

6. The Participatory, Performative Dimensions of Healing

Lastly, anthropology highlights the participatory, performative dimensions of healing. From shamanic rituals to community healing ceremonies, many traditions view health and illness not as individual mechanistic states, but as emergent properties of the whole interactive field. The “placebo effect” points to the power of meaning, relationality, and performance to shape embodied experience.

This invites psychology to consider how healing is co-created in the therapeutic relationship and broader social context. It suggests that therapy is not just an individual, internal process, but a relational, embodied one involving the performative evocation of new possibilities of experience. Approaches like psychodrama, Playback Theatre, and Theatre of the Oppressed use enactment and embodiment to help people expand their repertoire of roles and responses.

7. Moving Beyond Cognitivism: Emotion and the Irrational

From Ludwig Wittgenstein’s language games to William James’ radical empiricism, many philosophers have challenged psychology’s cognitivist bias, its tendency to privilege rational, linguistic thought over emotion, perception, and bodily feeling. They argue that much of mental life is fundamentally irrational, rooted in habits, impulses, and gut feelings that shape behavior beneath conscious awareness.

This critique aligns with recent developments in affective neuroscience and embodied cognition. Antonio Damasio’s work, for example, shows how emotions and bodily states undergird all thought and decision-making. Reason is not separate from passion, but permeated by it. Trauma studies likewise reveal how overwhelming experiences are encoded somatically, in implicit memory, inaccessible to talk therapy alone.

These perspectives invite psychology to decenter cognition and attend more fully to the irrational, embodied, affective dimensions of mind. They suggest that we can’t always think our way out of suffering, that healing must involve working with sensation, emotion, and physiological states. Therapies like Somatic Experiencing, EMDR, and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy engage the embodied, irrational psyche, rewiring the nervous system from the bottom up.

8. The Hermeneutics of Psychological Suffering

Philosophers like Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur developed the field of hermeneutics, the art and science of interpretation. They argued that human experience is always mediated by language, culture, and history – there is no view from nowhere, no God’s eye perspective outside the hermeneutic circle. We are always already interpreting, making sense from within our situated horizons.

Applied to psychology, a hermeneutic perspective suggests that symptoms and suffering are not brute facts, but embodied interpretations shaped by personal and cultural meaning systems. A hermeneutic approach asks not just what a symptom is, but what it means, what it reveals about a person’s being-in-the-world. Therapy becomes a collaborative process of deepening understanding, of exploring how a person’s complaints are situated in larger stories and systems.

This expands psychology’s horizons beyond the medical model of diagnosis and treatment. It honors the unique meaning of each person’s struggle, seeing symptoms not just as problems to solve, but as communications to decipher, carrying messages from the soul. A hermeneutic sensibility can help resist the pathologizing and objectifying gaze, keeping us attuned to the larger context and mystery of human being.

9. Transpersonal Dimensions of Consciousness

Another area where philosophy and anthropology can enrich psychology is in the study of transpersonal or anomalous states of consciousness. From William James’ investigations of religious experience to Mircea Eliade’s work on shamanism and the sacred, many thinkers have explored how altered states – whether induced by meditation, psychedelics, or spiritual practice – can yield profound insights and psychological transformations.

Anthropologists like Michael Winkelman have documented the worldwide use of ritually induced altered states for healing and self-discovery. Philosophers like Henri Bergson argued for the reality of mystical intuition, while William James coined the term “radical empiricism” to describe modes of knowing that transcend the subject-object divide.

These perspectives invite psychology to take seriously the transformative potential of non-ordinary states, whether referred to as peak experiences, flow states, or ego-transcendence. While altered states can be pathologized or dismissed as mere brain glitches, a growing body of research suggests they can also yield enduring increases in well-being, self-awareness, and prosocial behavior.

Transpersonal psychology, influenced by both Eastern contemplative traditions and depth psychology, has developed various practices for intentionally cultivating these states. Holotropic Breathwork, for example, uses intensive breathing to induce a non-ordinary state for emotional healing and existential insight. The current renaissance of psychedelic-assisted therapy likewise points to the potential of altered states to yield rapid, durable psychological transformation.

A transpersonal perspective reminds us that the farther reaches of human nature exceed our everyday egoic identities. By studying and supporting healthy transcendent experiences, psychology can help people access wider horizons of meaning, beauty, and connection.

10. The Social Unconscious: Culture, Power, and Psyche

A key insight of both critical theory and cultural psychology is that the unconscious is not just personal, but social and political. From Erich Fromm to Frantz Fanon, thinkers have explored how societal dynamics of power and oppression shape the psyche, often beneath awareness. Our deepest fears and fantasies, conflicts and complexes, bear the traces of the cultural-historical field.

This understanding challenges psychology to grapple more fully with the social determinants of health and illness. It suggests that we can’t understand or treat psychological suffering without considering the impact of systemic violence, marginalization, and inequality. Fanon, for example, argued that colonialism inflicts a “psychoaffective” damage that must be central to any project of decolonization.

Moreover, a social unconscious perspective reveals how clinical psychology and psychiatry themselves can function as instruments of social control, pathologizing difference and rebellion. From drapetomania to hysteria to schizophrenia, diagnostic labels have often served to naturalize and depoliticize what are fundamentally social, economic and existential crises.

Critical psychologists like Derek Hook draw on philosophers like Michel Foucault to examine how psychological discourses and practices reproduce relationships of power. By turning a reflexive gaze on the discipline itself, critical psychology invites greater humility and accountability, a reckoning with the ways clinical authority can perpetuate harm or reinforce the status quo.

At the same time, a social unconscious perspective affirms psychology’s potential as a tool for both personal and collective liberation. It calls on clinicians and researchers to make justice and equity central to therapeutic praxis, to disrupt cycles of oppression at multiple levels. Ultimately, it expands psychology’s circle of ethical concern beyond the intrapsychic to the interpersonal and institutional.

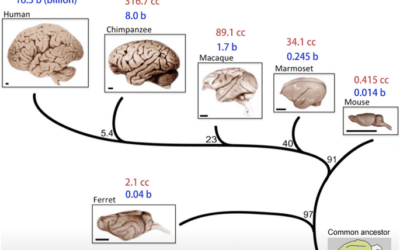

11. The Embodied and Extended Mind

The dominant paradigm in cognitive science has long been computationalism – the view that the mind is essentially a computer, a software program running on the brain’s hardware. But recent decades have seen the emergence of a radically different framework, that of embodied and extended cognition.

Drawing on philosophers like Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Martin Heidegger, this perspective holds that the mind is not confined to the skull, but intimately interwoven with the active, sensing, moving body. Cognition is not an abstract information processing system, but an embodied, embedded activity, shaped by the ecological niche of the organism.

Moreover, proponents of the extended mind thesis like Andy Clark argue that mental processes routinely incorporate external tools and technologies. When we use a notebook to offload memory or a calculator to augment mathematical reasoning, those devices become part of the cognitive system itself. The mind bleeds out into the world.

These ideas have profound implications for psychology. They suggest that we need to attend more carefully to the ways that thought, feeling and behavior emerge from the dynamic interaction of brain, body and environment. Mental health is not just an internal state, but a relational achievement, dependent on the affordances and constraints of the physical and social ecology.

An embodied, extended approach invites psychology to look beyond the individual to the distributed systems and scaffoldings that support cognition and wellbeing. It highlights the importance of cultivating environments that promote mental health, from green spaces and walkable cities to technologies of self-tracking and emotional regulation. By designing for the embodied mind, we can create a world that brings out the best in us.

12. The Existential and Phenomenological Roots of Psychotherapy

Many of the founders of humanistic and existential psychotherapy drew heavily on continental philosophy, especially phenomenology and existentialism. Thinkers like Rollo May, Irvin Yalom, and James Bugental were deeply influenced by philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Martin Heidegger, and Soren Kierkegaard.

Existential philosophy emphasizes the inescapable givens of the human condition – death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness. It sees anxiety and despair not as mere symptoms, but as ontological realities, intrinsic to the project of being human. For existential therapists, the goal is not to eliminate existential anxiety, but to help people face it with courage and authenticity.

Phenomenology, meanwhile, is the philosophical study of lived experience, of how phenomena appear to consciousness. Phenomenologists like Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty developed rigorous methods for bracketing assumptions and attending to the texture of direct, embodied experience.

Existential-phenomenological psychotherapy draws on these traditions to help people get in touch with their immediate, felt sense of being-in-the-world. Rather than focusing on unconscious drives or cognitive distortions, it invites a close, non-judgmental attention to the what and how of a person’s experiential flow. The aim is to help people take responsibility for the meaning they make of their lives.

These philosophical roots remind psychology that the human condition is irreducibly moral, existential and experiential. We are not just organisms responding to stimuli, but meaning-making beings grappling with the grand mysteries of existence. A psychology adequate to this must engage people as agentic subjects, not just passive objects of study.

13. Language, Thought and Reality

The relationship between language, thought and reality has long preoccupied philosophers and anthropologists. Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf famously argued that the structure of a language shapes the worldview of its speakers – that the categories and distinctions encoded in grammar influence how people perceive and conceptualize their experience.

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein likewise held that the limits of language are the limits of our world. He saw language not as a neutral medium for representing an external reality, but as a form of life, a toolkit for engaging in various social practices or “language games.” Meaning emerges from use, from how words are deployed in context.

These ideas challenge psychology’s often unexamined assumption of a language-independent reality that can be objectively described. They suggest that our most basic experience of self, others and world is always already structured by the linguistic frameworks we inhabit, frameworks that vary across cultures and subcultures.

Moreover, a language-based view highlights how psychological categories like emotion, motivation and mental health are not natural kinds, but cultural constructions. The way we narrate and label our experience shapes how we live it. Even our most private introspections bear the imprint of public symbols and storylines.

This perspective invites psychology to attend more carefully to the linguistic ecologies people dwell within. It highlights the power of reframing and renaming experience, of shifting limiting language patterns and self-narratives. Therapeutic practices like Narrative Therapy and Non-Violent Communication work with this transformative potential.

At the same time, a language-based view calls on psychology to examine its own role in constructing the realities it purports to describe. Diagnostic labels, theoretical constructs and research measures all feed back into the experience of those they are “about,” shaping identity and behavior in complex ways. We must wield our words with care and humility.

14. The Dialogical Self: Identity as Multiplicity

Most people have an intuitive sense of themselves as unitary and continuous, an “I” that persists as the subject behind diverse experiences. This is arguably a necessary fiction for navigating the social world – we need a coherent front to function. But postmodern thinkers have increasingly challenged this notion of a singular selfhood.

Philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin argued that the psyche is fundamentally polyphonic, a chorus of voices in constant dialogue and struggle. There is no unified author behind the cacophony, just an emergent, ever-shifting center of gravity. Similarly, Gilles Deleuze held that the self is better conceived as a multiplicity, a “assemblage of heterogeneous elements” with no fixed identity.

Anthropologists have explored how different cultures support different configurations of selfhood. In sociocentric societies, for example, people may experience themselves less as distinct individuals than as nodes in a relational web, constituted by their roles and responsibilities. The very idea of an autonomous, bounded self appears to be a peculiarly Western construct.

These perspectives invite psychology to question the unitary self that much of the discipline takes for granted. They suggest that intrapsychic conflicts – between, say, competing desires or self-aspects – are not aberrations to be resolved, but intrinsic to the nature of mind. Psychological health becomes less about integration than about flexibility, the capacity to fluidly enact different sub-selves in different contexts.

Therapeutic practices like Voice Dialogue, Internal Family Systems and Psychosynthesis work with this multiplicity. They help people identify and engage their various parts, often personified as sub-personalities with their own quirks and agendas. The goal is not to eliminate tension, but to foster an inner ecology of mutual understanding – a society of mind.

This dialogical perspective also highlights the intersubjective nature of selfhood, the way identity is negotiated and constructed through social interaction. We are always addressing and responding to others, real and imagined, external and internalized. The self is not a private citadel, but a public forum, a space of encounter.

15. The Situated Self: Mind in Context

Traditional Western psychology has tended to study the mind in isolation, as if it were separable from the concrete situations it finds itself in. Theories focus on intrapsychic structures and processes – schemas, traits, defense mechanisms – that are assumed to function independently of context. The self is treated as a fixed entity, a stable set of attributes.

But philosophers like Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre argued that we are always already “thrown” into a meaningful world, a pre-given web of projects, practices and concerns. The self is not a proscenium entity, a detached spectator, but a being-in-the-world, defined by its engagements and involvements. It has the mode of existence Heidegger calls “care.”

Similarly, social anthropologists have long emphasized how notions of personhood are culturally situated, how selves are constituted through participation in local forms of life. One’s sense of identity, agency and moral worth are inseparable from one’s place in a particular social milieu, with its network of roles, rituals and relationships.

These perspectives suggest that psychology needs to study the self-in-context, as a dynamic, adaptive process rather than a static essence. Mental states arise in and are indelibly shaped by the situations that afford them. Even seemingly solitary experiences like dreams and daydreams bear the imprint of the waking contexts we inhabit.

An ecological, situated approach also highlights how identities shift as people navigate different settings and social positions. We all contain multitudes, enacting different versions of ourselves depending on the cultural scripts and relational demands at play. The self is a fluid performance, not a fixed property.

This calls for a more holistic, context-sensitive approach to assessment and treatment. Rather than locating pathology solely within the individual psyche, we must attend to the systemic factors – familial, institutional, political – that constrain growth and wellbeing. Change becomes a matter of expanding the situations people have access to, the possible self-positions they can take up.

This also means recognizing how the therapeutic relationship itself is a unique social context that evokes particular modes of self-presentation and engagement. The way a person shows up in therapy both reveals and conceals aspects of their situated selfhood. We must work to create a space that invites relevant performances.

16. Reclaiming the Spiritual Dimension

Modern psychology emerged in the context of a scientific worldview that sharply separated matter from spirit, fact from value, nature from culture. In an effort to establish itself as a legitimate discipline, psychology largely adopted this dualistic, disenchanted framework. The mind was reduced to objective mechanisms, and spiritual concerns were bracketed out.

But for much of human history, psyche and spirit have been deeply interwoven. Traditional healing practices across cultures attend to the existential and transpersonal dimensions of wellbeing, the way personal suffering is bound up with larger questions of meaning, morality, and ultimate reality. The shaman is not just a proto-psychologist, but a mediator between worlds.

Even in the modern West, the founders of depth psychology recognized the spiritual function of the unconscious. Carl Jung saw the psyche as inherently religious, with dreams and symptoms expressing a drive towards wholeness and self-transcendence. Roberto Assagioli, the founder of Psychosynthesis, posited a “higher unconscious” as the source of our most exalted aspirations and peak experiences.

More recently, transpersonal psychology has attempted to reclaim this spiritual dimension, drawing on both Western and Eastern traditions of self-cultivation and self-knowledge. Figures like Stanislav Grof, Ken Wilber, and Michael Washburn have developed models of psychospiritual development that see personal growth as ultimately in the service of cosmic evolution.

This re-visioning challenges the reductionism and pathologism that often characterize conventional approaches to mental health. It recognizes that psychological distress is often entangled with deeper existential and spiritual malaise, a felt lack of belonging, purpose or connection to something greater. Healing must address these deeper strata.

A spiritually-informed psychology also affirms the transformative potential of altered states and contemplative practices. From meditation to psychedelics to prayer, various technologies of transcendence have been used across cultures to catalyze growth and self-expansion. By studying these phenomena, we can enrich our understanding of the farther reaches of human nature.

This is not to suggest that psychology become a religion, or that all therapists must hold particular metaphysical beliefs. But it does invite a more open and respectful engagement with the spiritual dimension of life, however conceived. It calls us to expand our notions of health and development beyond secular humanist assumptions.

Ultimately, a spiritually-informed psychology recognizes that the deepest well-springs of healing reside not in technique, but in the ineffable qualities of presence, compassion and heartful attunement that characterize the most transformative therapeutic relationships. It is in the meeting of psyche to psyche, soul to soul, that growth and resilience are found.

17. Archetypal Psychology: The Poetics of the Soul

One of the most innovative attempts to re-vision psychology through philosophy and the arts is archetypal psychology, a movement associated with James Hillman and other dissident post-Jungians. Drawing on Platonic and Neo-Platonic thought, Hillman sees the psyche not as a subjective entity, but as an objective field of autonomous images and fantasy-forms – the archetypes.

For Hillman, the archetypes are not just psychological, but ontological – they are the fundamental structures of reality itself. The soul is not “in” us; we are in the soul, just as we are in language. Psyche is poesis, the imaginative process by which the world comes to appear. All our experience is thus archetypal, shaped by the great myths and motifs that pattern existence.

The aim of archetypal psychology is not to cure or explain, but to deepen our experience by attending to its mythic resonances. When we literalize our stories, reducing Gods to concepts or complexes, we lose touch with the living mystery at the heart of things. The task is to “stick to the image,” to linger with the metaphorical rather than rushing to interpret.

This poetic sensibility calls for a radically different approach to practice. Rather than diagnosing disorders, the therapist “sees through” symptoms to the archetypal stories they tell. Depression becomes the descent of Inanna, anxiety the call of the Hero’s journey. The point is not to fix the problem, but to follow its narrative logic all the way down.

This de-literalizing move also applies to the self. For Hillman, the “ego” is just one figure among many, not the protagonist of the psyche. Therapy becomes a kind of polyphonic novel, in which we encounter the various characters and sub-plots that make up our stories. The goal is not to resolve conflicts, but to give each voice its due.

At the same time, archetypal psychology is deeply pragmatic, concerned with the soulful imagination of everyday life. Hillman argues that the ills of modernity – from ecological collapse to political corruption – ultimately stem from a failure of imagination, a literalism that reduces the world to dead matter and the self to an isolated ego. The cure is a re-ensouling of culture.

This expanded vision calls on therapists to become activists of the imagination, ministers of the mythic. It challenges us to look beyond the consulting room to the aesthetic dimensions of healing. By tending the stories and images that shape our world, we can participate in the poetics of psyche, the ongoing creation of a more soulful, artful existence.

18. Embodied Cognition and the Primacy of Perception

The mind-body problem has haunted psychology since its inception. Conventional approaches often treat cognition as a disembodied process, a program running on the brain’s hardware. But recent decades have seen an explosion of research on embodied, embedded, and enacted cognition, which sees the mind as intrinsically interwoven with bodily processes and environmental affordances.

One key figure in this turn is philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who argued for the primacy of perception in human experience. For Merleau-Ponty, we are first and foremost bodies-in-the-world, and all higher cognition is grounded in our pre-reflective, sensorimotor engagement with our surroundings.

Perception, in this view, is not a passive reception of stimuli, but an active process of meaning-making, a bodily dialogue with the environment. We don’t just perceive the world – we enact it through our exploratory movements and emotional attunements. Mind and body co-arise in the living flux of organism-environment interaction.

These ideas have been taken up by contemporary theorists like Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch, who argue that cognition is always situated, action-oriented, and affectively motivated. Even seemingly abstract processes like memory, language, and reasoning recruit bodily schemas and somatosensory simulations.

This paradigm shift has profound implications for psychology. It suggests that we need to attend much more carefully to the embodied, enactive dimensions of experience. Mental health is not just a matter of having the right beliefs or biochemistry, but of how we inhabit our bodily being-in-the-world. The felt sense of aliveness, vitality and agency arises from the dynamic coupling of brain, body and environment, not just from neural representations. Our very sense of self emerges from the sensorimotor coherence of our embodied interactions.

This has crucial implications for psychotherapy. It suggests that working with posture, gesture, movement and breath can directly influence cognitive-emotional states. Attending to non-verbal microbehaviors can reveal implicit patterns of engaging the world that underlie and sustain distress. Body-oriented therapies like Somatic Experiencing, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, and Hakomi work directly with these embodied dimensions.

At the same time, an enactive approach highlights how seemingly individual experiences are always shaped by our physical and social ecologies. Affordances for perception and action depend on the layout of our environments, from the architectural configurations of our dwellings to the technological extensions of our senses. Our bodily dispositions are molded by cultural practices and power relations.

Consider, for example, how gender norms around taking up space and self-presentation become sedimented in muscle memory and embodied habit. Experiences of bodily constriction or expansion, comfort or awkwardness, are never purely personal – they reflect our social embedding, our position in fields of affordances and expectations.

Thus an embodied, enactive psychology must attend to the systemic factors that scaffold lived experience. Interventions need to target not just individual mindsets, but the interpersonal patterns and material conditions that shape our bodily being-in-the-world. This might involve modifying physical environments, social arrangements, or cultural practices to better support thriving.

Here we might take inspiration from somatic practices in other cultures that work directly with the bodymind in context. Many traditional healing systems see individual wellbeing as inseparable from communal and cosmic attunement. Rituals involving dance, song, touch, and entheogenic medicines aim to transform collective body-world relations.

An embodied psychology might also challenge Western notions of health as a personal commodity, a matter of optimizing individual bodies and brains. What if we saw wellbeing as a relational achievement, a function of our shared habits of sensing, moving, and interacting? How might we design environments and practices that invite more nourishing forms of bodily becoming?

In grappling with these questions, psychology might draw on the ethological concept of umwelt, the lived perceptual world specific to an organism. As Jakob von Uexküll argued, each creature inhabits its own phenomenal universe, shaped by its sensorimotor capacities and life activities. A tick, a dog, and a human will experience the same meadow in radically different ways.

We might extend this idea to the felt worlds of people in different cultural and subcultural niches. An embodied psychology would be curious about the diverse ways of sensing, feeling and being afforded by different forms of life – across genders, ethnicities, classes, and subcultures. By illuminating these varied bodily microworlds, we can expand our understanding of human possibility.

The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty spoke of the body as our “general medium for having a world.” As psychology reckons with the profound implications of embodied cognition, it has an opportunity to radically reimagine its concepts and practices. We must learn to see subjects not as minds housed in bodies, but as bodily beings in motion, in meaning and making.

19. Intersubjectivity and the Relational Mind

In recent decades, psychology has undergone a “relational turn,” a shift from seeing the mind as fundamentally individual to seeing it as fundamentally social. Drawing on philosophy, anthropology, and infant research, relational theorists argue that psychological processes emerge from our basic embeddedness in a world of others.

One key construct here is intersubjectivity, the sharing of subjective states between two or more minds. As Colwyn Trevarthen and others have shown, infants are born ready to engage in rich protoconversations, choreographing their expressions, vocalizations and gestures in rhythmic attunement with caregivers. We come into being through these early “dances of intimacy.”

Crucially, such intersubjective communion precedes and grounds the development of individual subjectivity. Infants first experience mental states – intentions, feelings, desires – in the embodied back-and-forth with others. Only gradually do they learn to attribute inner experiences to a bounded self. Even then, our moment-by-moment consciousness remains indelibly social.

As the philosopher Daniel Stern argues, the self is not a pre-given entity that enters into relationships, but an emergent property of relating. We are born into a phenomenal world of “we-centric” space, and carve out a sense of “I” through patterns of interpersonal engagement. The mind is not an “inside” set against an “outside,” but an intersubjective field.

These ideas have been elaborated by relational psychoanalysts like Stephen Mitchell, who see the clinical encounter as a meeting of subjectivities. From this view, transference is not a distortion, but the very medium of therapeutic action. As therapist and patient enact and reflect on their here-and-now dynamic, they generate new possibilities for relating.

A relational perspective also highlights how larger cultural patterns of intersubjectivity shape development. Anthropologists have shown how different ethnotheories of mind and personhood are enacted in everyday caregiver-child interactions. The Western ideal of an autonomous, introspective self is not universal, but reflects particular practices of attention and attribution.

Consider, for example, how the phenomenon of shame differs across cultures. In interdependent contexts, shame is less about individual moral failing than about potential damage to social bonds. The visceral experience of withdrawal serves to reinforce communal values and obligations. A relational psychology must grapple with these cultural variations.

Intersubjectivity has also been studied in phenomenological and embodied cognition traditions. Thinkers like Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty argued that we experience the world not as isolated subjects confronting external objects, but as co-conscious participants in a shared field of meaning. Perception and action are fundamentally relational, a reciprocal “coupling” between living bodies.

From a philosophical perspective, intersubjectivity poses challenges to traditional Western notions of the self as a private, interior realm. Our most intimate experiences – of desire, memory, even sensation – are permeated by otherness. And our agency and autonomy are always constrained by our existential interdependence, our inextricable entanglement with human and nonhuman actors.

At the same time, a relational perspective offers profound ethical insights. It calls on us to see ourselves not as self-contained entities, but as nodes in vast networks of kinship and reciprocity. Our actions always already implicate others; we are inescapably responsible. An intersubjective ethics involves recognizing how we are shaped by and answerable to a world beyond ourselves.

For psychology, embracing intersubjectivity means radically decentering the individual mind. We cannot understand a person’s struggles or strengths in isolation, but only as emerging from a lifeworld of relationships – familial, cultural, ecological. Change is not just an internal process, but involves reconfiguring relational and narrative fields.

This might involve helping people experientially re-embody different patterns of interaction, whether through role play, somatic work or psychodrama. It might mean working explicitly with interpersonal dynamics as they arise in the therapy room, and inviting clients to experiment with new possibilities for connection and expression. The aim is not just insight, but enactment.

It also means attending more carefully to the relational matrices that generate health and resilience. How can we build families, communities, and institutions that better scaffold thriving? What social practices and ritual forms promote mutual understanding and care? Here psychology might partner with other disciplines to imagine a more relational world.

Ultimately, seeing intersubjectivity as fundamental to mind invites profound humility and wonder. We are not self-made, but interdependently originated. Even in our most private musings, we find the traces of countless others, proximal and distant, human and more-than-human. Expanding our circle of intimacy and ethical regard is perhaps the deepest work we can do.

20. Cultural Psychology and the Importance of Meaning

From its inception, psychology has grappled with the tension between universality and cultural diversity. Early thinkers like Wilhelm Wundt and Franz Boas argued that mental processes are profoundly shaped by social context. But as the discipline became increasingly focused on individuals and experiments, cultural considerations faded to the background.

In recent decades, however, cultural psychology has re-emerged as a vital force, challenging the field’s often unexamined assumptions about human nature. Thinkers like Richard Shweder, Hazel Markus and Shinobu Kitayama have shown how psychological processes are constituted through local patterns of meaning and practice. The mind is not a natural object, but a biosocial-cultural hybrid.

One key insight of cultural psychology is that human experience is fundamentally mediated by systems of symbols, narratives, and norms. We don’t just perceive a pre-given reality, but actively construct worlds of significance. Even seemingly basic processes like perception, emotion and motivation carry the imprint of culturally patterned sense-making.

Take the experience of happiness. In individualistic cultures, happiness is often seen as a personal achievement, a positive internal state to be pursued and maximized. In more collectivistic contexts, happiness may be more about fulfilling social roles and contributing to group harmony. The very meaning and felt texture of wellbeing differs.

These differences have profound implications for how we understand and treat psychological suffering. Distress that seems dysfunctional from one cultural framework may be a legitimate response to moral or interpersonal predicaments in another. Imposing Western diagnostic categories and treatments globally can be a form of colonial violence.

Cultural psychology invites us to radically pluralize our notions of the good life and the healthy mind. It challenges the tendency to see WEIRD populations (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) as the norm from which others deviate. By illuminating diverse forms of flourishing and meaning-making, it expands our imagination of human possibility.

At the same time, cultural psychology highlights the transformative power of meaning. Practices of healing and resilience across cultures often work by shifting the way people make sense of their experience – whether through ritual, narrative reframing or altered states of consciousness. By changing meaning, we change our embodied, enacted lifeworlds.

Consider a phenomenon like Hearing Voices. In biomedical frameworks, voice-hearing is often seen as a meaningless symptom of brain pathology. But the Hearing Voices Movement has shown how validating and engaging with voices as meaningful entities can reduce their disruptive impact. Making sense together matters.

Cultural psychology also reveals how the self is fundamentally a product of meaning-making. We become who we are by appropriating the signs, stories, and social performances available in our cultural surround. Identity is not an inner essence, but a dynamic positioning in semiotic space, a fluid improvisational dance with the symbolic resources at hand.

This view has been elaborated by thinkers like Jerome Bruner, who saw selfhood as a narrative achievement. We are the stories we tell about ourselves, in dialogue with the stories others tell about us. Agency lies in our capacity to re-author our lives, to take up new possibilities from the cultural repertoire.

For psychology, this means attending much more carefully to the meaning-laden ecologies people inhabit. We need to explore how particular cultural worlds afford and constrain different trajectories of becoming. And we must be reflexive about how our own theories and practices reproduce particular visions of the good life, often in the guise of neutral science.

A meaning-centered psychology would also prioritize narrative and symbolic practices of transformation. It would recognize therapy as a collaborative process of meaning-making, of co-constructing more livable accounts of self and world. This might involve drawing on cultural resources like myths, metaphors, and rituals to expand clients’ interpretive horizons.

At the same time, a meaning-centered approach must grapple with issues of power. Meaning-making happens in contexts of inequality, where some stories and selves are privileged over others. Psychology must be attuned to how dominant cultural narratives can oppress and constrain, and work to amplify marginalized voices and visions.

Here we might take inspiration from liberation psychology, which sees mental health as inseparable from social justice. Thinkers like Frantz Fanon and Ignacio Martín-Baró argued that psychology must be a tool for decolonizing minds and transforming oppressive conditions. This means working not just at the individual level, but partnering with communities to create more inclusive and empowering cultural worlds.

Ultimately, seeing meaning as fundamental to mind invites a profound re-visioning of psychology’s role. We are not just scientists of behavior, but scholars and practitioners of the human arts of meaning. Our task is not just to describe the world, but to envision and enact more just and joyful forms of life. This is a creative and ethical calling, one that demands ongoing dialogue with the wisdom of other cultures and disciplines.

21. Contemplative Science and the Transformation of Consciousness

In recent decades, there has been a surge of interest in the meeting of Western psychology and contemplative traditions from around the world. Contemplative practices like mindfulness, yoga, and compassion meditation are being studied for their potential to promote health, wellbeing, and human flourishing. This has given rise to a new interdisciplinary field known as contemplative science.

At the heart of this field is a profound insight from contemplative traditions: that the mind is not a fixed entity, but a malleable process that can be cultivated and transformed through practice. Meditation is not just a stress reduction technique, but a radical technology of consciousness that can fundamentally alter our way of being in the world.

This view challenges the often unexamined assumption in Western psychology that the normal adult mind is a given, a natural state that arises from brain development. Contemplative traditions suggest that our ordinary consciousness – dominated by discursive thought, habitual reactivity, and a sense of separateness – is actually quite dysfunctional, a source of great suffering.

Through sustained practice, however, it is possible to transform the mind, to cultivate states of profound clarity, equanimity, and care. Advanced meditators report experiences of selflessness, timelessness, and nondual awareness that far exceed the usual understanding of mental health. These states are not seen as aberrations, but as potentials available to all humans.

Western psychology has often been skeptical of these claims, dismissing them as subjective or culturally relative. But the rise of contemplative science is challenging this skepticism. Using rigorous methods from cognitive neuroscience, researchers are showing that contemplative practices can indeed produce measurable changes in brain function and structure.

For example, studies have found that mindfulness meditation can enhance attention, working memory, and emotional regulation. Compassion practices have been shown to boost empathy, altruism, and prosocial behavior. And long-term meditators display distinct patterns of neural activity, including increased integration between brain regions and reduced default mode network activation.

These findings suggest that the mind is indeed plastic, and that contemplative practices can be powerful tools for self-transformation. But contemplative science is not just about confirming ancient wisdom with modern methods. It is also about expanding our very understanding of the mind and its possibilities.

One key area of exploration is the nature of selfhood. Many contemplative traditions posit that our usual sense of being a separate, unchanging self is an illusion, a construct that creates suffering. Through practices like self-inquiry and nondual awareness, it is possible to experientially deconstruct this illusion and abide in a more open, fluid mode of being.

0 Comments