This article contains mild spoilers from the series.

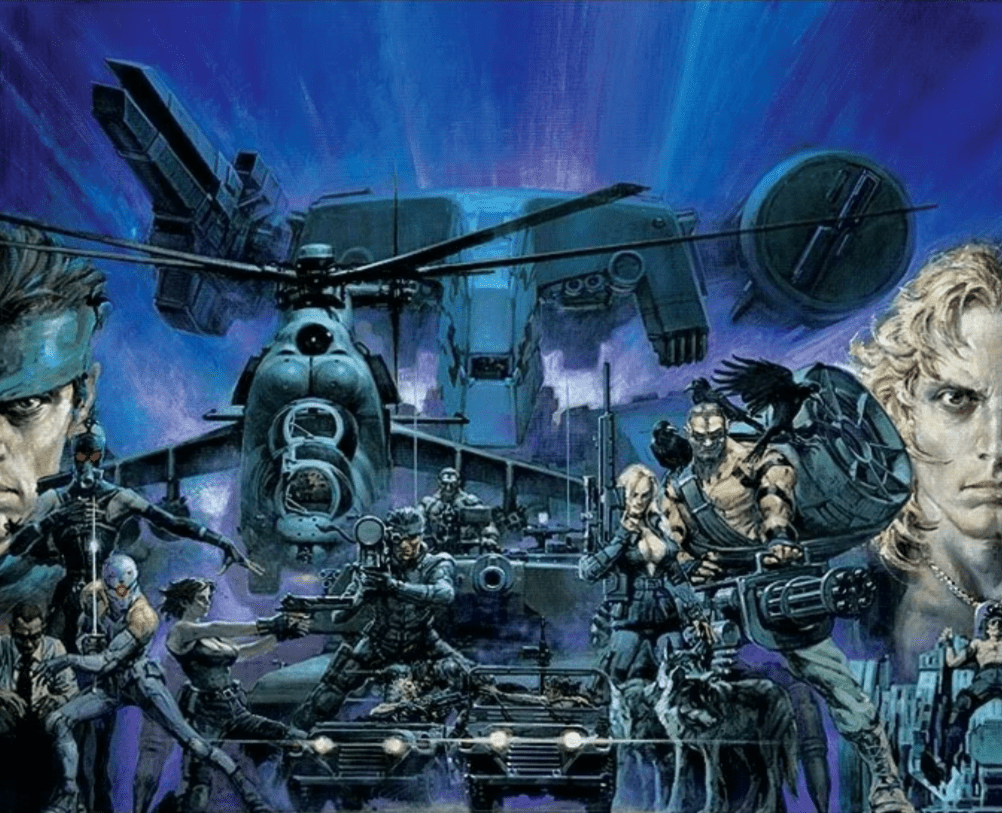

Metal Gear Solid stands as one of gaming’s most psychologically complex franchises, not because it tries to be, but because Hideo Kojima possesses an almost preternatural ability to understand the tensions between what we claim to value and the forces that actually drive our society. The series doesn’t predict the future so much as it excavates the present, finding in our contemporary anxieties the seeds of tomorrow’s crises. Each game functions as a psychological case study, using gameplay mechanics, narrative structure, and even musical choices to explore how technology, warfare, and identity intersect in ways that feel both deeply prophetic and somehow irrelevant, like a brilliant therapist who diagnoses society’s neuroses without necessarily trying to cure them.

What makes Kojima’s work particularly fascinating from a psychological perspective is how it operates on multiple levels simultaneously. On the surface, these are action games about super soldiers and giant robots. Beneath that lies a sophisticated examination of post-traumatic stress, intergenerational trauma, and the ways technology mediates and manipulates human consciousness. Deeper still, the games interrogate the very nature of identity in an age where genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and information warfare have made the question “Who am I?” both more urgent and more impossible to answer than ever before.

The Soldier’s Fractured Self: Metal Gear Solid (1998)

The original Metal Gear Solid introduces us to the fundamental psychological wound at the series’ heart: the soldier’s fragmented identity. Solid Snake embodies the dissociative state required for modern warfare. He is simultaneously a person and a weapon, a human being and a code name. This duality isn’t merely narrative; it’s built into the very structure of how we interact with him. When we play as Snake, we experience this fragmentation firsthand. We are both observer and participant, controlling a character who is himself controlled by forces beyond his understanding.

The game’s mechanics reinforce this split in profound ways. Stealth gameplay forces players to suppress natural fight or flight responses, to become invisible, to deny the self in service of the mission. The radar system creates a kind of double consciousness where we must simultaneously inhabit Snake’s limited first-person perspective and the god’s-eye view of surveillance technology. This mechanical tension mirrors the psychological tension of modern soldiers who must be both human agents capable of moral judgment and instruments of state power programmed to follow orders.

The recurring motif of genetic destiny versus individual choice plays out through the Les Enfants Terribles project, a government program that created Snake and his brothers as clones of the legendary soldier Big Boss. Snake discovering he’s a clone forces us to confront questions about nature versus nurture that psychology has grappled with for decades. But Kojima pushes beyond simple genetic determinism. The game asks: if you’re engineered to be a soldier, do you have a self beyond that function? The answer remains deliberately ambiguous, mirroring real veterans’ struggles with identity after service.

Consider the character of Otacon, whose very name (derived from “Otaku Convention”) signals his retreat into technology and fiction as a response to familial trauma. His relationship with Snake offers a different model of masculinity than the hypermasculine warrior archetype, one based on vulnerability, intellectual connection, and mutual support. Yet even this relationship is mediated by technology (codec calls) and shadowed by Otacon’s guilt over creating weapons of mass destruction. The game suggests that in the modern world, all relationships are technologically mediated and ethically compromised.

The Shadow Moses incident itself functions as a microcosm of Cold War psychology transplanted into the post-Cold War era. The threat of nuclear annihilation, which had structured global psychology for decades, returns not as state policy but as rogue action. This shift from institutional to individual nuclear threat reflects a broader psychological transition from collective to individualized anxiety that would define the coming decades.

Musically, the game’s synthetic, electronic score by TAPPY, Kazuki Muraoka, and others creates an atmosphere of technological coldness punctuated by moments of unexpected humanity. The main theme, with its militaristic drums and synthesized orchestra, establishes a sonic palette that is both epic and artificial. But it’s in quieter moments that the game’s psychological depth emerges. “Enclosure,” which plays during Snake’s torture, uses dissonance and industrial sounds to aurally represent psychological breakdown. “The Best Is Yet To Come,” sung in Gaelic by Aoife Ní Fhearraigh, speaks to the erosion of cultural identity in the face of globalized warfare. The choice of Gaelic is particularly poignant, suggesting that what’s being lost in modern warfare isn’t just individual lives but entire ways of being human.

Information as Virus: Metal Gear Solid 2 and the Post-Truth World

MGS2 arrived in 2001 but feels like it was written yesterday, or perhaps tomorrow. The game’s central preoccupation with information control, digital identity, and the nature of truth in a mediated reality channels Marshall McLuhan’s prophetic understanding that the medium is the message. But where McLuhan was describing television’s impact on consciousness, Kojima anticipated the internet’s transformation of reality itself into an infinitely manipulable data stream.

The game perfectly embodies what we now call metamodern sensibility, that oscillation between sincerity and irony, between constructed truth and genuine feeling. Raiden’s struggle to distinguish reality from simulation mirrors the metamodern linguistic turn where we speak both literally and symbolically simultaneously, never quite sure which register we’re operating in.

The game’s most audacious move, switching protagonists from the beloved Solid Snake to the rookie Raiden, was widely criticized at release but now seems prophetically brilliant. Raiden represents us, the players, in a way Snake never could. He’s trained entirely through VR simulations, his understanding of warfare coming not from experience but from media representations of experience. His bleached hair, androgynous appearance, and emotional vulnerability marked him as everything Snake wasn’t, forcing players to confront their own investment in masculine military fantasies.

The S3 Plan, revealed to be not Solid Snake Simulation but Selection for Societal Sanity, presents a chilling vision of AI curated reality that predates our current struggles with algorithmic echo chambers by two decades. The Patriots’ AI system doesn’t control through force but through information management, creating contexts that guide human behavior while maintaining the illusion of free will. This is Foucauldian power at its most sophisticated: not disciplining bodies but shaping the very conditions of possibility for thought and action.

The game’s exploration of memetics, ideas as self-replicating cultural DNA, anticipated how social media would transform information into a kind of cognitive virus, spreading and mutating through networks faster than human reason can process. The colonel’s famous speech about creating context rather than content perfectly describes how contemporary algorithms shape reality by controlling not what we think but what we think about.

Raiden’s journey is fundamentally about the psychology of the digital native, someone whose entire understanding of reality comes through screens and simulations. His relationship with Rose, revealed to potentially be an AI construct, explores how digital mediation affects our capacity for authentic human connection. Their conversations, which interrupt gameplay at seemingly random moments, force us to experience the intrusion of personal life into professional space, the collapse of public and private that defines digital existence.

The game’s treatment of identity is particularly prescient. Raiden’s past as a child soldier named Jack the Ripper, suppressed and rewritten, mirrors how digital platforms allow us to construct and reconstruct identity at will. The question “Who is Raiden?” has no stable answer. He’s simultaneously Jack, Raiden, Snake (in simulation), and the player’s avatar. This multiplicity of identity, which seemed abstract in 2001, now describes the everyday experience of maintaining different personas across various digital platforms.

The La-Li-Lu-Le-Lo, the Patriots’ name filtered through nanomachine censorship, represents the limits of language under systemic control. Characters literally cannot speak truth to power because power has colonized language itself. This linguistic control anticipates how platform moderation, SEO optimization, and algorithmic recommendation systems shape not just what we can say but what we can think.

The soundtrack, composed by Harry Gregson-Williams with additional music by Norihiko Hibino, shifts from the previous game’s electronic coldness to a more cinematic, orchestral approach that paradoxically makes everything feel less real, as if we’re trapped in a movie about our own lives, which is exactly Raiden’s predicament. The main theme’s sweeping strings and heroic brass feel like they belong to a different story, one where heroes and villains are clearly defined, creating a sonic dissonance with the game’s moral ambiguity. The track “Arsenal’s Guts” uses industrial sounds and distorted samples to create an audio landscape of systemic breakdown, while “Can’t Say Goodbye to Yesterday” by Carla White provides a melancholic reflection on lost innocence and irrecoverable past.

The End of Ideology: Metal Gear Solid 3’s Darwinian Psychology

Set during the Cold War, MGS3: Snake Eater explores the transition from the ideological certainties of the modern period to the post-ideological world that would follow. By returning to the 1960s, Kojima creates temporal distance that allows for psychological clarity. We see the origins of the conspiracy, the birth of the Patriots, the moment when ideological warfare transformed into something else entirely.

This temporal regression reveals what cultural theorists now recognize as the shift from modern to postmodern to metamodern, each paradigm containing the seeds of its own undoing. The Cold War’s binary opposition between capitalism and communism represents peak modernism, with its faith in grand narratives and universal truths. But already we can see the cracks forming, the moment when ideology reveals itself as performance.

The game’s survival mechanics reduce human motivation to its most basic biological imperatives. Hunting, eating, treating wounds: these systems strip away ideological justification to reveal raw survival instinct. What you eat dies; what doesn’t eat you, you become. This isn’t just gameplay; it’s a psychological thesis. The game suggests that beneath the grand narratives of capitalism versus communism lies a more primitive psychology of survival and dominance.

The introduction of CQC (Close Quarters Combat) creates a new intimacy with violence. Unlike previous games’ distant gunplay, CQC forces physical contact with enemies. You feel their breathing, their struggle, the moment they lose consciousness. This tactile violence serves a psychological purpose, making us complicit in brutality we might otherwise abstract. The ability to interrogate enemies, to extract information through threat and coercion, implicates players in the moral compromises of intelligence gathering.

The relationship between Naked Snake (Big Boss) and The Boss explores how ideological betrayal creates psychological trauma that reverberates through generations. The Boss’s defection and ultimate sacrifice reveal ideology itself to be a kind of performance, a necessary fiction that gives meaning to violence. Her final words about loyalty to the mission rather than the nation prefigure the post-national, corporate warfare of later games. But more than that, her sacrifice represents the ultimate psychological double bind: she must be remembered as a traitor to be honored as a hero, must be hated to be loved, must die to give life meaning.

The Philosophers’ Legacy, a massive fund created by the allied powers during World War II, represents capital freed from national interest, money as pure power without ideological attachment. This transformation of wealth from means to end mirrors the psychological shift from external to internal motivation that characterizes late capitalism. The characters fight not for country or cause but for control of capital that has become its own justification.

The game’s theme song, “Snake Eater,” performed by Cynthia Harrell with composition by Norihiko Hibino, creates a nostalgic longing for a time when enemies were clear and motivations simple, a psychological defense against the moral ambiguity that defines contemporary conflict. The song’s lyrics about thrilling darkness and silence romanticize solitary struggle while acknowledging its ultimate futility. The orchestral score throughout the game, also by Hibino and including tracks like “Virtuous Mission” and “Shagohod,” evokes 1960s spy films but with a melancholic undertone that suggests we’re watching the end of something rather than the beginning.

War as Product: Metal Gear Solid 4 and the Pentagon of Power

MGS4 presents war not as a means to an end but as the end itself, the ultimate product of late capitalism. This represents what psychotherapy critics call the illusion of progress, the false promise that technological advancement equals human advancement. Lewis Mumford’s concept of the pentagon of power finds its full expression in the game’s war economy, where conflict is deliberately perpetuated for profit.

The game’s aging Snake becomes a metaphor for the psychological toll of perpetual warfare and the failure of modernist promises of transformation. His rapid aging isn’t just biological but psychological. Each mission ages him months, each battle years. He represents a generation of soldiers used up and discarded by the military industrial complex, but also something more: the aging of war itself as a coherent human activity. Snake’s decrepit body, maintained by regular injections and barely holding together, mirrors how contemporary warfare is kept functional through technological intervention despite having lost its essential human meaning.

The Beauty and the Beast Unit, with their traumatic backstories triggering PTSD-induced transformations, literalizes how war trauma reshapes identity at the most fundamental level. Each Beast represents a different response to trauma: Laughing Octopus’s fractured identity, Raging Raven’s explosive anger, Crying Wolf’s frozen grief, and Screaming Mantis’s controlled controller. Their beauty forms, revealed when the beast armor is destroyed, suggest that beneath mechanized violence lies human vulnerability, but a vulnerability so damaged it can only express itself through further violence.

The nanomachine-controlled battlefield, where soldiers’ emotions are regulated by technology, explores the militarization of psychology itself. The System represents the ultimate expression of behavioral control, not through ideology or coercion, but through direct manipulation of neurochemistry. Soldiers don’t choose to be brave or calm; these states are induced technologically. This pharmaceutical management of combat psychology anticipates our current era of widespread psychopharmacological intervention, where mood and behavior are increasingly seen as chemical problems requiring chemical solutions.

Liquid Ocelot’s plan to destroy the System initially seems liberating, but the chaos that ensues when soldiers regain their suppressed emotions reveals the deeper horror: we’ve become so dependent on technological emotional regulation that authentic feeling is itself traumatic. The return of repressed emotion doesn’t bring freedom but breakdown, suggesting that some forms of control have become so integrated into our psychology that their removal is more destructive than their presence.

The soundtrack by Harry Gregson-Williams, Nobuko Toda, and others creates melancholic orchestral pieces that mourn entire ways of understanding human conflict. “Old Snake” uses a lonely saxophone over military drums to evoke both nostalgia and decay. “Father and Son” builds to an emotional crescendo that feels like a farewell not just to characters but to an entire era of warfare. Most significantly, “Here’s to You” by Lisbeth Scott, based on Joan Baez’s tribute to executed anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, connects Snake’s struggle to a longer history of resistance against systemic power. The song’s placement at the end of Snake’s story suggests that individual resistance, however heroic, cannot stop the systematic transformation of human conflict into commodity. The repetition of “Here’s to you, Nicola and Bart” becomes a haunting refrain for all those sacrificed to systems they cannot defeat.

Phantom Pain and Historical Amnesia: MGSV’s Psychology of Repetition

The Phantom Pain confronts us with the ultimate psychological horror: the inability to learn from history, doomed to repeat it while believing we’re making progress. This is metamodernism’s oscillation taken to its darkest conclusion, where we swing between hope and despair without ever achieving synthesis or resolution. Set in Afghanistan and Africa, locations that would become central to 21st-century conflict, the game explores how secret operations, false flags, and proxy wars create a historical record so fragmented that understanding cause and effect becomes impossible.

The game’s open-world structure represents a fundamental shift in how we experience both games and history. There’s no longer a linear narrative to follow, no clear progression from beginning to end. Instead, we have an endless series of deployments, extractions, and base management that mirrors the contemporary psychology of permanent military engagement. This structure embodies what contemporary theorists call the postmodern condition, where grand narratives collapse into fragments and meaning becomes endlessly deferred.

The vocal cord parasites that drive much of the game’s plot represent the weaponization of language itself. The parasite kills those who speak specific languages, literalizing how linguistic and cultural identity can become targets of genocide. This language virus serves as a perfect metaphor for how information and communication, the very tools we use to understand and connect with each other, can be turned into weapons of mass destruction. In an era of information warfare, the game suggests, words themselves become potentially lethal, and silence becomes the only defense against linguistic annihilation.

The parasites also represent a more subtle form of control than previous games’ nanomachines. Where nanomachines controlled behavior directly, the parasites make certain behaviors, specifically speaking your native language, literally fatal. This creates a psychology of self-censorship, where people police their own expression not because they’re commanded to but because expression itself has become dangerous. The parallel to contemporary online discourse, where a single poorly chosen word can trigger devastating consequences, feels deliberately drawn.

The reveal that we’re not playing as Big Boss but as his body double, a medic brainwashed into believing he’s someone else, serves as the game’s master metaphor. The phantom pain of the title isn’t just about missing limbs but missing memories, missing contexts, missing truths. We experience what psychologists call “confabulation,” the creation of false memories to fill gaps in experience. The game suggests we all participate in historical narratives that may be fundamentally false, creating coherent stories from fragments and assuming causality where only correlation exists.

The hospital sequence that opens the game establishes this theme of uncertain identity from the start. Awakening from a nine-year coma, unable to speak, forced to relearn basic movement, we experience complete psychological disorientation. The sequence’s surreal imagery suggests that the boundary between hallucination and reality has collapsed. This isn’t just PTSD; it’s reality itself becoming traumatized, unable to maintain consistent narrative structure.

Skull Face, the game’s antagonist, embodies the psychology of linguistic trauma. His face destroyed, his language erased, he exists as a living absence, a phantom pain in human form. His plan to destroy English as a lingua franca through the parasite represents not just revenge but an attempt to trauma-bond humanity through shared loss. If everyone loses their language, his loss becomes universal, his individual trauma becomes historical truth.

Mother Base itself becomes a character, growing from nothing to a massive military platform through our actions. But this growth feels hollow, accumulative rather than developmental. We extract soldiers, resources, and weapons from the field, building our private army, but to what end? The base-building mechanics mirror contemporary social media psychology: endless accumulation of followers, likes, and content that never coheres into meaningful connection or purpose.

Musically, the game’s use of 1980s pop songs creates temporal dislocation that reinforces themes of repetition and simulation. “The Man Who Sold the World” by Midge Ure (covering David Bowie) plays both diegetically and non-diegetically, breaking the fourth wall between game and player. “Nuclear” by Mike Oldfield, with its lyrics about nuclear weapons and deterrence, sounds both dated and terrifyingly current. “Sins of the Father” by Donna Burke serves as the game’s main theme, its lyrics about phantom pain and endless revenge cycles capturing the game’s core themes. The extensive use of cassette tapes for crucial narrative information suggests that truth exists but only in fragments, accessible but requiring active searching and careful listening.

The silence forced by the vocal cord parasites stands in stark contrast to this musical backdrop. Characters who cannot speak, who must communicate through gesture and action rather than words, highlight how trauma can rob us of our voice even as history continues its noisy march.

The Hero’s Journey, Interrupted

Throughout the series, Metal Gear Solid deconstructs Joseph Campbell’s monomyth by showing us characters frozen at various stages of development, unable to complete their psychological evolution. The hero’s journey assumes growth, learning, and eventual return with wisdom to share. But Metal Gear’s characters are stuck in endless recursion, repeating their traumas rather than transcending them.

Big Boss can’t move past the mentor’s betrayal. The Boss’s sacrifice becomes the defining moment of his life, but he fundamentally misunderstands its meaning, creating Outer Heaven not as a place free from the control of governments but as his own form of control. His inability to process this trauma leads him to recreate it, forcing his “sons” to experience their own betrayals and sacrifices.

Solid Snake can’t integrate his shadow self. His brothers, Liquid and Solidus, represent aspects of himself he refuses to acknowledge. Rather than achieving individuation through confronting and accepting these shadow elements, he destroys them, maintaining his fragmented identity through violence rather than healing it through integration.

Raiden can’t distinguish reality from simulation. Even after the events of MGS2, in Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance, he’s still searching for his own identity, his own purpose beyond what others have programmed into him. His cyborg body represents the ultimate failure of the hero’s journey. Rather than returning home transformed, he’s been literally rebuilt, his humanity replaced with machinery.

Ocelot spends six games playing roles within roles, never revealing a true self that may not exist. Is he loyal to Big Boss? The Patriots? His own agenda? The game suggests these questions miss the point. Ocelot has become pure performance, identity as endless masquerade. He represents the postmodern condition taken to its logical extreme, where authentic self is not hidden but absent.

The games suggest that the modern condition, especially for soldiers but ultimately for all of us living in technologically mediated, perpetually surveilled, endlessly manipulated reality, makes completing the hero’s journey impossible. We’re all stuck in our own phantom pain, fighting wars that never end, for reasons we can’t remember, toward goals that keep shifting.

This interruption of the hero’s journey reflects a broader psychological truth about contemporary life. The traditional markers of adulthood and completion have become increasingly inaccessible or irrelevant. We live in permanent adolescence, always preparing for a future that never arrives, accumulating experiences that don’t add up to wisdom.

Trauma as the Engine of History

What makes Metal Gear Solid psychologically profound isn’t just its ability to predict specific technologies or political events, but its understanding that trauma, whether personal, cultural, or global, is what ultimately moves history forward. Every major character is driven by unprocessed trauma: Big Boss by The Boss’s betrayal, Solid Snake by his genetic origin, Otacon by his family’s nuclear legacy, Raiden by his child soldier past. These individual traumas mirror and create larger cultural traumas: the atomic bombings that haunt Japanese consciousness, the Cold War’s ideological scars, the endless wars of the 21st century.

The series reveals how trauma operates across scales, creating what we might call a “trauma economy.” Personal trauma becomes political action as Big Boss’s pain drives him to create Outer Heaven. Political action creates cultural trauma as the war economy traumatizes entire societies. Cultural trauma shapes global conflict as traumatized nations perpetuate cycles of violence. And global conflict creates new personal traumas in an endless cycle, each generation inheriting and amplifying the wounds of the previous one.

The Patriots, the series’ ultimate antagonists, are literally an AI system born from the traumatic realization that human judgment led to nuclear near-annihilation. Even our systems of control are traumatized, responding to historical wounds with increasingly desperate attempts at management and manipulation. The AIs don’t hate humanity; they’re trying to protect it from itself, but their protection becomes another form of trauma, a suffocating control that prevents growth even as it prevents catastrophe.

The Les Enfants Terribles project literalizes intergenerational trauma: trauma made genetic, passed down not through experience but through engineered biology. Snake and his brothers don’t just inherit Big Boss’s genes; they inherit his purpose, his conflicts, his unresolved psychological tensions. They’re born into trauma, created to embody and perpetuate it.

The language virus in MGSV represents perhaps the series’ most disturbing vision of weaponized trauma: the ability to make entire cultures literally unspeakable, to traumatize not just individuals but languages themselves out of existence. It suggests that in our age of information warfare, trauma can be encoded into the very medium of human communication, making connection itself dangerous. When words become weapons, silence becomes both symptom and defense.

The Digital Double Bind

Metal Gear Solid 2’s exploration of digital identity has proven more prescient with each passing year. The game presents us with a fundamental double bind: we need digital technology to navigate modern reality, but that same technology undermines our ability to distinguish reality from simulation. This isn’t just about “fake news” or deep fakes. It’s about how digital mediation fundamentally alters consciousness itself.

The codec conversations throughout the series exemplify this bind. Characters communicate through digital interfaces that both connect and separate them. They can transmit information instantly across any distance, but they can’t touch, can’t fully verify the humanity of the person on the other end. Every relationship is mediated, filtered through technology that enables connection while preventing true intimacy.

The series suggests that we’re all becoming like Raiden: digital natives whose primary experiences are mediated, whose memories are unreliable, whose identities are constructed rather than developed. The question “Who am I?” becomes unanswerable when the self is distributed across platforms, profiles, and personas that may be more real to others than our physical presence.

The Prophet in the Machine

Kojima’s prophetic vision extends beyond predicting specific technologies to understanding the psychological transformations they enable. He understood that the internet wouldn’t just change how we communicate but who we are. That genetic engineering wouldn’t just modify bodies but reimagine identity. That AI wouldn’t just process information but reshape reality.

The series anticipates what Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism,” the extraction of human behavior as raw material for predictive products. The Patriots’ system of control through information management prefigures how tech platforms shape behavior through algorithmic recommendation, turning free will into a carefully managed illusion.

But perhaps Kojima’s deepest insight is that these technological transformations don’t replace human psychology so much as reveal it. The willingness to accept comfortable lies over difficult truths, the tendency to repeat trauma rather than resolve it, the desire for simple enemies and clear missions in an ambiguous world: these aren’t bugs in human consciousness but features, exploited by systems of control but not created by them.

The Therapeutic Impossibility

Throughout the series, characters attempt various forms of therapy or healing, but the games suggest that in a systematically traumatized world, individual healing might be impossible. Snake’s accelerated aging can’t be stopped, only managed. Raiden’s memories can’t be recovered, only reconstructed. Big Boss’s understanding of The Boss’s will can’t be corrected, only revealed too late to matter.

This therapeutic pessimism reflects a broader truth about contemporary psychology. We live in what Mark Fisher called “capitalist realism,” the inability to imagine alternatives to current systems. When trauma is systemic, when the entire social order is organized around perpetuating rather than healing wounds, individual therapy becomes a form of symptom management rather than cure.

Yet the games don’t counsel despair. Characters continue to struggle, to seek connection, to fight for meaning even in a meaningless world. Snake’s final message to live not for nations or ideologies but for the future suggests that while healing might be impossible, resistance remains necessary. We can’t escape the cycle of trauma, but we can try to minimize the damage we pass on.

Musical Architecture of Consciousness

The series’ use of music deserves deeper consideration as a tool for psychological exploration. Each game’s soundtrack doesn’t just accompany the action but structures consciousness, creating emotional architectures that shape how we process the narrative.

The recurring “Metal Gear Solid Main Theme,” before its removal due to plagiarism concerns, served as a musical anchor across games, its militaristic drums and soaring strings creating continuity across discontinuous narratives. Its absence in later games creates a sonic phantom pain, a missing musical limb that emphasizes the series’ themes of loss and incompleteness.

The vocal tracks across the series chart an emotional journey from hope to despair and back again. “The Best Is Yet To Come” in MGS1 suggests possibility despite loss. “Can’t Say Goodbye to Yesterday” in MGS2 mourns an irrecoverable past. “Snake Eater” in MGS3 romanticizes a simpler time that never really existed. “Here’s to You” in MGS4, with its dedication to Sacco and Vanzetti, transforms individual sacrifice into historical memory. “Sins of the Father” in MGSV acknowledges that we inherit not just genes but grievances, not just bodies but burdens.

The use of in-game radio adds another layer. From Snake Eater’s diegetic music that affects Snake’s stamina to MGSV’s cassette tapes that blur the line between soundtrack and story, the games use music to explore how sound shapes consciousness. The ability to play custom music in MGSV’s helicopter turns players into DJs of their own war experience, aestheticizing violence through playlist curation.

The Codec as Confession Booth

The codec conversations that interrupt gameplay throughout the series function as a kind of digital confession booth, a space for psychological intimacy within mechanical violence. These conversations, often lengthy and philosophical, force players to stop acting and start thinking, to shift from motor cortex to prefrontal cortex engagement.

These interruptions serve a therapeutic function, allowing characters to process their experiences in real-time. But they also highlight the fragmentary nature of digital communication: voices without bodies, words without context, connection without presence. The codec creates intimacy and distance simultaneously, much like contemporary digital communication platforms.

The evolution of these conversations across the series mirrors our changing relationship with digital communication. In MGS1, codec calls feel like genuine connection. By MGS2, we’re unsure if we’re talking to humans or AIs. MGS3’s radio provides practical survival tips alongside existential philosophy. MGS4’s video calls show aged faces and tired eyes. MGSV largely abandons codec conversations for cassette tapes, one-way communications that emphasize isolation over connection.

The Phantom Future

In the face of technological acceleration, information warfare, and the dissolution of stable identity, the Metal Gear series suggests that trauma isn’t just a psychological response but the fundamental force that shapes human events. We don’t progress beyond our wounds; we encode them into our technologies, our institutions, our very DNA.

The franchise stands as a monument to the psychology of our transitional moment, caught between human and posthuman, meaning and meaninglessness, playing out scenarios of agency while suspecting we might be following a script written by our collective wounds. It’s therapy for a condition that hasn’t been named yet, medicine for a disease we’re still developing.

Metal Gear Solid doesn’t offer solutions because it understands that the problems it diagnoses are not bugs but features of contemporary existence. The series’ ultimate message might be that in a world where reality itself has become unreliable, where identity is endlessly malleable, where trauma is the engine of history, the best we can do is maintain awareness of our condition. Like Snake’s cardboard box, absurd, ineffective, yet somehow essential, our coping mechanisms might not solve our problems, but they help us navigate them.

The games achieve what great art should: they make the familiar strange and the strange familiar. They show us ourselves refracted through the lens of science fiction, revealing truths that realism couldn’t capture. In their convoluted plots and philosophical pretensions, in their mixture of profound insight and adolescent excess, they mirror the confusion and complexity of contemporary consciousness.

And like all great psychological literature, Metal Gear Solid doesn’t cure us so much as help us recognize ourselves in the symptoms, finding in that recognition not healing (the series is too honest for that) but at least the dignity of understanding that our pain, personal and collective, is what makes us human in an increasingly inhuman world.

In the end, Metal Gear Solid reveals that history itself might be nothing more than the story of trauma seeking resolution but finding only repetition, each generation passing its wounds to the next, disguised as progress, marketed as evolution, but always, always, the same phantom pain in search of a body that no longer exists.

The series leaves us with a paradox: we can’t heal from trauma that’s ongoing, can’t wake from a nightmare we’re actively creating, can’t complete a journey that has no destination. But in recognizing this, in seeing the system for what it is, we achieve a kind of freedom. Not the freedom to escape but the freedom to understand our captivity.

And here’s the thing: confronted with all this trauma, we can’t just hide in a cardboard box. Go to therapy. Not because it will solve the systemic issues the games diagnose, but because understanding our individual position within these systems, processing our personal instantiation of collective trauma, might be the first step toward imagining something different. The games show us the disease; therapy might not cure it, but it can help us live with greater awareness and intentionality within it.

Metal Gear Solid’s ultimate achievement is making us feel the weight of contemporary existence with all its impossibilities, contradictions, and recursive traumas, while maintaining just enough hope to keep playing. In that tension between despair and determination, between understanding our situation and refusing to accept it, lies whatever possibility remains for human agency in an inhuman world. The phantom pain might never heal, but at least we can name it, and in naming it, retain some measure of what makes us human.

0 Comments