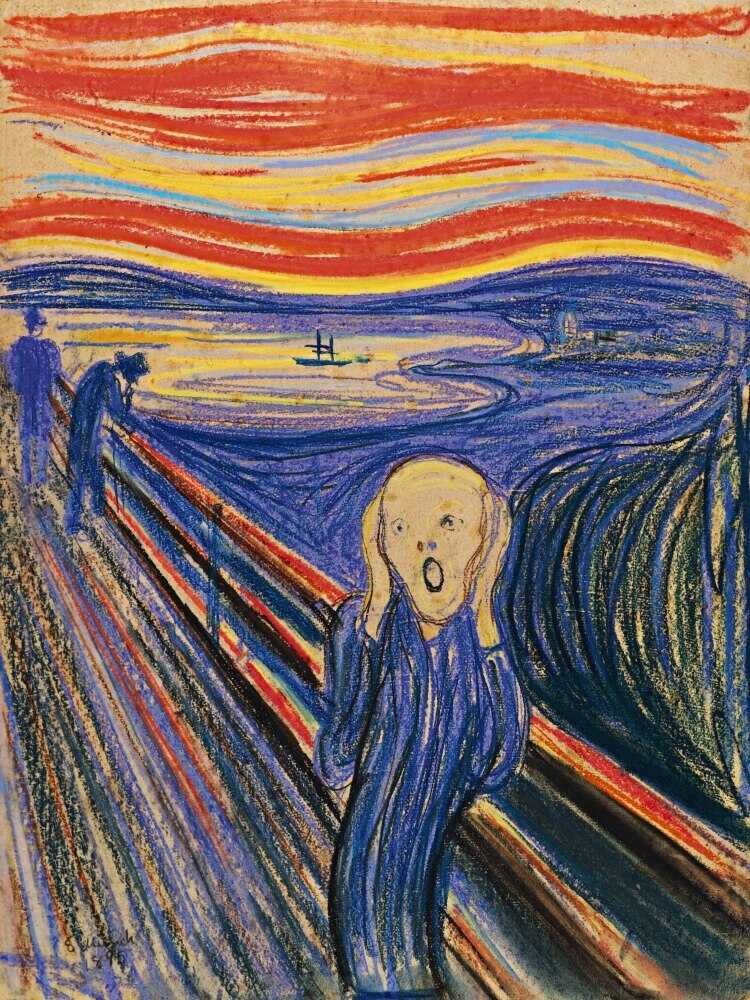

The Scream made by Edvard Munch

Healing the Modern Soul is a series about how clinical psychology will have to change and confront its past if it is to remain relevant in the future. Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Healing the Modern Soul Appendix

Suffering Without Screaming

In the first part of this series, we explored the concept of the modern world as a simulacrum, a copy without an original, and how this phenomenon is related to the increasing emphasis on hyper-rationality and objectivity in our culture. We also discussed how the work of philosophers and psychologists, as observed by Friedrich Nietzsche, can reveal their own fears and insecurities through their insistence on perfect logic and objectivity. In the second part of the series we discussed the need for a coherent sense of self in new therapy models and a dialectical relationship between the self and the world.

Key Ideas and Main Points:

- The modern world can be understood as a simulacrum – a copy without an original. This is related to the increasing emphasis on hyper-rationality and objectivity in our culture.

- Philosophers and psychologists who insist on perfect logic and objectivity may be revealing their own fears and insecurities, as observed by Nietzsche.

- New therapy models need to account for a coherent sense of self and the dialectical relationship between self and world.

- The simulacra effect creates a disconnect between the hyper-real external world and our authentic felt experiences. Psychotherapy needs to help individuals reconnect with their subjective experiences.

- Some therapy models like ABA that focus only on external behaviors while ignoring inner experiences are problematic. Therapy should support the development of a coherent sense of self.

- Implicit memories and subconscious processes profoundly shape our sense of self in ways that are hard to articulate. Therapy needs to work with these implicit memories to promote healing.

- Different types of traumatic memory (relational, visual, kinesthetic, cognitive) require different therapeutic approaches.

- The unconscious mind is too complex to be perfectly captured by language and conscious models. It’s more like a computer’s GPU while the conscious mind is the CPU.

- The influence of corporate interests and the attempt to make humans programmable like computers leads to dehumanizing assumptions in some therapy models. People can’t be reduced to robots.

- Therapy should help people find meaning and sit with the full human experience, not just help them “suffer without screaming.” The capacity for love and empathy, not just enduring pain, is key to healing in the modern world.

William Gibson, Memory Palace

When we were only several hundred-thousand years old, we built stone circles, water clocks.

Later, someone forged an iron spring.

Set clockwork running.

Imagined grid-lines on a globe.

Cathedrals are like machines to finding the soul; bells of clock towers stitch the sleeper’s dreams together.

You see; so we’ve always been on our way to this new place—that is no place, really—but it is real.

It’s our nature to represent: we’re the animal that represents, the sole and only maker of maps.

And if our weakness has been to confuse the bright and bloody colors of our calendars with the true weather of days, and the parchment’s territory of our maps with the land spread out before us—never mind.

We have always been on our way to this new place—that is no place, really—but it is real.

The Simulacra Effect and the Disconnect from Felt Experience

The simulacra effect, as described by Jean Baudrillard, is a result of our culture’s increasing emphasis on hyper-rationality and objectivity. As we prioritize logical and rational thinking over subjective experiences and emotions, we create a world that feels hyper-real, yet simultaneously disconnected from our authentic selves.

Nietzsche recognized this phenomenon in the work of philosophers and psychologists who claimed to have discovered objective truths through pure logic and reason. He argued that the more these thinkers insisted on their own rationality and objectivity, the more they revealed their own madness and disconnection from reality.

In today’s world, we find ourselves in a similar situation. On the surface, everything appears normal and rational, but there is an underlying sense of wrongness or disconnection that we struggle to articulate. This is because our culture has taught us to prioritize objective, rational thinking over our subjective, felt experiences.

As individuals and as a society, we must reconnect with our felt experiences to recognize and address the insanity that surrounds us. This requires us to embrace our emotions, intuitions, and subjective perceptions, even when they seem to contradict the dominant narrative of rationality and objectivity.

Psychotherapy, as a discipline, must play a crucial role in helping individuals engage with their felt experiences, even if it means navigating the complex and often paradoxical relationship between the rational and the subjective. By doing so, therapy can help individuals develop a more authentic sense of self and a deeper understanding of their place in the world.

The Dangers of Denying the Self in Psychotherapy Models

In the second part of this series, we explored how different models of psychotherapy reveal their own assumptions and biases about the nature of the self and the goals of therapy. By examining these models through the lens of Nietzsche’s critique, we can identify potentially dangerous or dehumanizing approaches to treatment.

One particularly concerning example is Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), a common approach to treating autism spectrum disorders. In the ABA model, the self is reduced to a collection of observable behaviors, with little or no consideration for the individual’s inner world, emotions, or subjective experiences.

This approach is deeply problematic, as it essentially denies the existence of a soul or psyche in individuals with autism or other neurodivergent conditions. By focusing solely on external behaviors and reinforcing “desirable” actions through rewards and punishments, ABA fails to recognize the inherent humanity and agency of the individuals it seeks to treat.

In contrast, a truly effective and ethical model of psychotherapy must acknowledge and support the development of a coherent sense of self, while also recognizing the existence of other selves in the world. Therapy should be a dialectical process, helping individuals navigate the complex relationship between their inner world and the external reality they inhabit.

This is particularly important for individuals who may not fit neatly into the objective, outcome-oriented modes of expression and socialization that dominate our culture. Rather than discounting or suppressing their unique perspectives and experiences, therapy should encourage and support the development of their authentic selves.

The Case of the Autistic Child and Neuromodulation

To illustrate the importance of a holistic and integrative approach to psychotherapy, let us consider the case of an autistic child who experiences sensory overwhelm and distress when exposed to cold temperatures. In a traditional ABA approach, the focus would be on modifying the child’s behavior through rewards and punishments, with the goal of reducing the outward expression of distress.

However, this approach fails to address the underlying neural and sensory processing issues that contribute to the child’s experience of overwhelm. By contrast, a neuromodulation approach, such as that described in the case study involving QEEG brain mapping, seeks to identify and target the specific areas of neural dysfunction that are contributing to the child’s distress.

In this case, the QEEG brain map revealed a disconnect between the thalamus, which processes sensory information, and the long-term memory regions of the brain. By using neuromodulation techniques to bridge this gap and facilitate communication between these areas, the therapists were able to help the child process and integrate their sensory experiences more effectively, leading to a reduction in distress and an increased ability to tolerate cold temperatures.

This case study highlights the importance of looking beyond surface-level behaviors and considering the complex interplay of neurological, sensory, and emotional factors that shape an individual’s experience of the world. By addressing these underlying issues, rather than simply trying to suppress or modify outward expressions of distress, psychotherapy can help individuals to develop a greater sense of self-regulation, resilience, and overall well-being.

The Role of Implicit Memory in Shaping Our Sense of Self

To effectively address the complexities of the modern soul, psychotherapy must also grapple with the role of implicit memory in shaping our sense of self and our relationship to the world. Implicit memory, also known as the unconscious or subcortical brain processes, encompasses the vast array of experiences, emotions, and assumptions that operate beneath the level of conscious awareness.

These implicit memories can have a profound impact on our behavior, relationships, and overall well-being, often in ways that we struggle to understand or articulate. They may manifest as trauma responses, maladaptive patterns of thinking and behavior, or a pervasive sense of disconnection from ourselves and others.

Effective psychotherapy must find ways to access and work with these implicit memories, helping individuals to process and integrate their experiences in a way that promotes healing and growth.

Different Types of Memory and Therapeutic Approaches

One key insight in understanding the role of implicit memory in psychotherapy is recognizing that there are different types of memory, each requiring distinct therapeutic approaches to effectively treat the associated trauma or dysfunction.

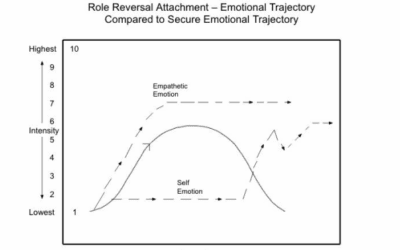

Relational memory:

This type of memory encompasses our assumptions about communication, identity, and how we want to be perceived by others. Individuals with attachment disorders or relational trauma may have impaired functional memory, leading to maladaptive patterns in their interactions with others. Therapies that focus on building secure attachments, such as emotionally focused therapy (EFT) or interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), can be particularly effective in addressing relational memory issues.

Visual-spatial memory:

This type of memory is associated with flashbacks and vivid re-experiencing of traumatic events. While relatively rare, visual-spatial memory trauma can be highly distressing and debilitating. Treatments like eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and prolonged exposure therapy (PE) have been shown to be effective in processing and integrating these traumatic memories.

Kinesthetic memory:

This type of memory is stored in the body and is related to how we budget energy and respond to stress. Somatic therapies, such as sensorimotor psychotherapy and somatic experiencing, can help individuals reconnect with their bodily sensations and develop greater self-regulation and resilience in the face of stress and trauma.

Cognitive-emotional memory:

This type of memory is associated with self-referential processes, such as problem-solving, obsessing, and rumination. Cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) and mindfulness-based approaches can be effective in addressing maladaptive thought patterns and promoting more flexible and adaptive ways of relating to one’s internal experience.

By understanding the different types of memory involved in trauma and psychological distress, therapists can develop more targeted and effective interventions that address the specific needs of each individual client.

The Complexity of the Unconscious and the Limitations of Language

While different psychotherapeutic approaches have their own conceptions of the unconscious, it is important to recognize that implicit memory cannot be perfectly mapped or described using language alone. The unconscious is a vast and complex realm that operates beneath the level of conscious awareness, and our attempts to understand and articulate its workings will always be limited by the constraints of language and cognition.

In many ways, the relationship between the conscious mind and the unconscious can be likened to that between a democratic government and its constituents. Just as a democracy relies on elected representatives to make decisions on behalf of the larger population, our conscious mind relies on simplified models and representations of the unconscious to guide our thoughts and behaviors.

Similarly, the unconscious can be compared to a graphics processing unit (GPU) in a computer, which is optimized for handling complex and repetitive tasks, such as rendering images or processing large datasets. In contrast, the conscious mind is more like a central processing unit (CPU), which is better suited for handling novel and sequential tasks that require flexibility and adaptability.

While the CPU (conscious mind) may be the “decision-maker,” it relies heavily on the GPU (unconscious) to provide the raw data and processing power needed to navigate the complexities of the world around us. Attempting to understand the unconscious solely through the lens of conscious, language-based reasoning would be like trying to understand the inner workings of a GPU using only the tools and concepts of CPU programming.

The Influence of Silicon Valley and Corporate Interests on Mental Health

This brings us to the problematic assumptions underlying certain models of psychotherapy, which are deeply embedded in the broader cultural and economic forces that shape our understanding of mental health and well-being.

In particular, the influence of Silicon Valley and corporate interests on the field of psychology has led to a growing emphasis on treating individuals as programmable entities, much like computers or robots. This perspective is rooted in the belief that with enough data and processing power, human behavior can be predicted, controlled, and optimized.

We see this belief reflected in the development of large language models (LLMs) and other AI technologies, which are often presented as capable of replicating or even surpassing human intelligence and creativity. However, this view fundamentally misunderstands the nature of human consciousness and agency, reducing the complexity of the human mind to a set of algorithms and data points.

The notion that robots can be made into people through advances in AI and computing power is deeply misguided, as it fails to recognize the fundamental differences between human consciousness and machine learning. At the same time, the idea that people can be reduced to robots through behavioral conditioning and programming is equally dangerous, as it denies the inherent humanity and agency of individuals.

These assumptions are not only flawed but also deeply dehumanizing, as they prioritize measurable outcomes and “optimal” functioning over the rich and complex inner lives of individuals. By treating people as objects to be fixed or optimized, rather than as meaning-making beings with unique subjective experiences, we risk perpetuating a culture of alienation, disconnection, and suffering.

The Danger of Prioritizing Suffering Over Healing

The case of the autistic child also raises important questions about the goals and priorities of psychotherapy in the modern world. In a culture that prioritizes hyper-rationality, objectivity, and measurable outcomes, there is a risk of reducing the complexity of human experience to a set of behaviors to be modified or eliminated.

This approach can lead to a dangerous prioritization of suffering over healing, where the goal of therapy becomes to help individuals endure their distress without expressing it, rather than to address the underlying causes of their suffering and promote genuine growth and transformation.

The idea that therapy should aim to help people “suffer without screaming” is a deeply troubling direction for the profession to take. It reflects a dehumanizing view of individuals as objects to be fixed or controlled, rather than as complex, meaning-making beings with inherent worth and dignity.

Instead, psychotherapy should strive to create a safe and supportive space for individuals to explore their experiences, to develop a greater understanding of themselves and their place in the world, and to cultivate the skills and resources needed to navigate life’s challenges with resilience, authenticity, and grace.

This requires a willingness to sit with the full spectrum of human experience, including the painful, messy, and often paradoxical aspects of the self and the world. It also requires a recognition of the inherent value and wisdom of each individual’s unique perspective and life journey, and a commitment to honoring and supporting their growth and development in a way that is grounded in their own values, needs, and aspirations.

Screaming without Suffering

The simulacra effect, as described by Baudrillard and anticipated by Nietzsche, is a direct consequence of our culture’s increasing emphasis on hyper-rationality, objectivity, and the denial of subjective experience. As psychotherapists and as a society, we must resist the temptation to reduce the complexity of the human mind to a set of behaviors or data points, and instead embrace the inherent messiness and uncertainty of the human condition.

By reconnecting with our felt experiences, acknowledging the existence of the self and other selves in the world, and challenging the dominant paradigms of mental health treatment, we can begin to navigate the complexities of the modern soul and find a sense of authenticity and meaning in an increasingly disconnected world.

This requires a willingness to engage with the paradoxes and contradictions that arise when we attempt to bridge the gap between the rational and the subjective, the individual and the collective, the inner world and the external reality. It is a difficult and ongoing process, but one that is essential if we are to create a more humane and fulfilling vision of mental health and well-being in the 21st century.

As we have explored throughout this series, the role of psychotherapy in navigating the modern soul is both complex and essential. By embracing a holistic and integrative approach that recognizes the full complexity of the human experience, therapists can help individuals to develop a more authentic and meaningful sense of self, one that is grounded in their own unique values, experiences, and relationships.

This process of self-discovery and healing is not always comfortable or easy, but it is necessary if we are to resist the dehumanizing forces of hyper-rationality, objectivity, and corporate interest that threaten to reduce the richness and diversity of human experience to a set of measurable outcomes and data points.

Ultimately, the goal of psychotherapy in the modern world should be to help individuals to connect with their own inner wisdom and resilience, to find meaning and purpose in their lives, and to contribute to the creation of a more compassionate and authentic society. By working together to navigate the complexities of the modern soul, we can begin to heal the wounds of disconnection and alienation, and to create a world that truly honors the full spectrum of human experience.

In the end, it is our capacity for love, empathy, and genuine human connection that will guide us through the challenges of the modern world. While pain and suffering may be inevitable, it is our ability to love and be loved that gives our lives meaning and purpose. As we strive to navigate the complexities of the modern soul, let us remember that we have the power to choose love over fear, connection over isolation, and authenticity over simulacra. For in doing so, we not only heal ourselves but also contribute to the healing of the world around us.

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom”

-Viktor E. Frankl

Read More About Evidence Based Practice and Research Psychology:

Lessons from the STAR*D Scandal

The Corporatization of Healthcare

Incentives in Evidence Based Practice

Psychotherapy is Indivisible form Philosophy and Anthropology

The Broken Incetives in Research and Clinical Practice

Healing The Modern Soul Series Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Healing the Modern Soul Appendix

References and Further Reading:

Baudrillard, J. (1981). Simulacra and simulation. University of Michigan Press.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

Deleuze, G. (1968). Difference and repetition. Columbia University Press.

Gibson, W. (1984). Neuromancer. Ace Books.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. W.W. Norton & Company.

Jung, C. G. (1933). Modern man in search of a soul. Routledge.

Nietzsche, F. (1882). The gay science. Vintage.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

Schore, A. N. (2019). The development of the unconscious mind. W.W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. W.W. Norton & Company.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Žižek, S. (1989). The sublime object of ideology. Verso.

Baudrillard, J. (1994). The illusion of the end. Stanford University Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1980). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

Lacan, J. (1966). Écrits. W.W. Norton & Company.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1979). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. University of Minnesota Press.

Saussure, F. (1916). Course in general linguistics. Columbia University Press.

Derrida, J. (1967). Of grammatology. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1887). On the genealogy of morality. Hackett Publishing Company.

Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and time. Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Sartre, J.-P. (1943). Being and nothingness. Washington Square Press.

Camus, A. (1942). The stranger. Vintage International.26. Dostoevsky, F. (1866). Crime and punishment. Penguin Classics.

Kafka, F. (1915). The metamorphosis. Classix Press.

Borges, J. L. (1944). Ficciones. Grove Press.

Calvino, I. (1972). Invisible cities. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Eco, U. (1980). The name of the rose. Harcourt.

Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Putnam.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. Oxford University Press.

LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon & Schuster.

Solms, M., & Turnbull, O. (2002). The brain and the inner world: An introduction to the neuroscience of subjective experience. Other Press.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. Other Press.

Stern, D. N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant: A view from psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. Basic Books.

Tronick, E. (2007). The neurobehavioral and social-emotional development of infants and children. W.W. Norton & Company.

Beebe, B., & Lachmann, F. M. (2014). The origins of attachment: Infant research and adult treatment. Routledge.

Schore, J. R., & Schore, A. N. (2008). Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clinical Social Work Journal, 36(1), 9-20.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W.W. Norton & Company.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jungian Thought to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

0 Comments