Thomas Pynchon reportedly said about Gravity’s Rainbow, though the quote may be apocryphal, “If I’d written this as nonfiction, the CIA would have killed me.” Whether real or invented, this captures what both Pynchon and Kojima understand: certain truths about power under late capitalism require the protective absurdity of fiction to be told at all.

Thomas Pynchon reportedly said about Gravity’s Rainbow, though the quote may be apocryphal, “If I’d written this as nonfiction, the CIA would have killed me.” Whether real or invented, this captures what both Pynchon and Kojima understand: certain truths about power under late capitalism require the protective absurdity of fiction to be told at all.

Authors Note: This Article Contains Spoilers for the Metal Gear Solid Series

The Shared Territory of Pynchon and Kojima

Gravity’s Rainbow and Metal Gear Solid explore the same psychohistorical rupture: the moment when World War II’s moral clarity collapsed into paranoid systems where cause and effect became untraceable. Both document Operation Paperclip’s transformation of Nazi scientists into American assets, revealing how defeating evil meant absorbing it. The V-2 rockets that terrorized London became the ICBMs pointed at Moscow. The surveillance techniques developed for wartime became peacetime’s permanent architecture.

For Pynchon, this manifests as encyclopedic paranoia where every connection might be real or madness, where the rainbow of gravity describes both the rocket’s arc and humanity’s inevitable entropic fall. For Kojima, it manifests as literal identity loss to larger systems. Nanomachines colonize consciousness. The boundary between human and weapon dissolves. Each escape attempt creates more sophisticated control. When I am not doing therapy in Alabama I am usually reading or playing MGS.

Both creators wrap their insights in protective absurdity. Pynchon’s giant adenoid attacking London serves the same function as Kojima’s whale on fire: signaling we’ve entered a space where normal rules don’t apply, where horror and comedy become indistinguishable responses to incomprehensible systems. The silly anime elements aren’t decoration but essential camouflage, allowing Kojima to make games where U.S. Marines commit war crimes at Guantanamo Bay, where Camp Omega becomes playable space, where the American military-industrial complex is consistent antagonist across decades.

Anime’s Psychological Architecture and Historical Grounding

Kojima’s genius lies in fusing anime and manga’s psychological vocabulary with brutal historical reality. Anime tradition treats villains as embodiments of specific psychological states, reducing conflict to essential components while studying psychology through lenses of belief, religion, magic, and the supernatural. This recognizes a fundamental truth: we will always have magic and the supernatural because we will always have psychology. The human mind creates demons to explain suffering as surely as it creates language.

The Cobra Unit demonstrates this perfectly. Each member represents trauma response made flesh, their origins deliberately kept ambiguous yet clearly rooted in warfare’s horrors. We know they fought in World War II, that battlefield experiences somehow birthed their supernatural abilities, that they embody different aspects of combat’s psychological toll. The Pain controls hornets, his body a living hive—perhaps bodies on beaches attracted swarms, perhaps not. The Fear disappears into invisibility, anxiety made literal. The End waits with photosynthetic patience, depression’s vegetative state spanning decades. The Fury burns with jetpack rage, lifted from normal existence by trauma. The Sorrow walks between worlds, carrying ghosts that never left him.

The games never fully explain these transformations, and that ambiguity is the point. War’s effect on consciousness resists clean narrative. The gap between natural and supernatural collapses under sufficient trauma. These aren’t mere boss fights but psychological states requiring comprehension rather than domination to defeat. Pure anime logic: external conflict as internal struggle manifest. When Psycho Mantis reads your memory card and moves your controller, the moment works on every level simultaneously: supernatural (psychic powers), technological (PlayStation hardware), psychological (dissociation from trauma), and historical (Soviet psychic research programs). The magic is real because consciousness exists.

From Genre Celebration to Deconstruction

Metal Gear began as Kojima’s love letter to the spy thrillers that shaped his imagination. The gadgets and one-liners of 1960s Cold War espionage. The 1980s action heroes fighting communist threats. Escape from New York gave Solid Snake his name and eyepatch. Early Metal Gear celebrated these tropes purely, reveling in the genre that birthed it.

But as the series progressed, Kojima fell out of love with his influences. Each spy thriller convention revealed dark historical secrets when examined closely. The Cold War wasn’t noble opposition but proxy wars destroying developing nations. The 1980s action hero wasn’t liberator but imperial agent. Clear enemies became murky. Simple missions revealed complex manipulations. Heroes exposed themselves as traumatized killers. Kojima came to reconsider the motivations and methods from those periods, recognizing how propaganda had warped history itself.

This disillusionment runs parallel to the historical progression the games document. Metal Gear Solid 3’s 1960s setting still allows for belief in its genre even while questioning it. By Metal Gear Solid 1 and 2’s near-future, genre conventions have hollowed out. Snake isn’t a dashing spy but a depressed soldier. Villains aren’t foreign threats but rogue American forces. Nuclear danger comes from within. Metal Gear Solid 4 and 5 complete the deconstruction. War is product, soldiers are customers, violence is content. The 1980s setting of MGSV should be peak action movie territory, but instead delivers child soldiers, biological weapons destroying languages, torture as gameplay mechanic.

The Boss’s Eden: Spiritual Vision Versus Material Reality

Metal Gear Solid 3 presents the last believers in modernity‘s promises. The Boss works for the CIA. She and the Cobra Unit fought World War II. They aren’t yet jaded like Snake becomes. They still believe in grand narratives, grand villains, grand solutions. The Boss imagines borderless worlds because borders still mean something definite to her generation.

The Boss’s vision represents both beauty and impossibility. She describes an Eden state, unity that Kojima suggests we should aspire toward while knowing it’s unachievable. The divisions created by modernity, accelerating through postmodernity into metamodernism, mean clear boundaries can never return. We can pretend them, imagine them, hallucinate them, but humanity has become something fundamentally internetworked.

The crucial tragedy: The Boss never presents this as concrete plan but as spiritual orientation. Big Boss’s fundamental error is trying to build her vision through military force. Zero makes the opposite error, attempting unity through information control. Both men literalize what was meant as consciousness, creating the very systems that destroy meaning. Their modernist actions birth postmodernism’s conditions. The Boss mothering Ocelot and sacrificing herself produces his cynical consciousness. Big Boss creating Outer Heaven and body doubles generates metamodern identity crisis.

Villains as Crystallized Trauma

Metal Gear’s antagonists embody warfare’s psychological devastation so completely they cease existing as individuals. Each becomes possessed by specific aspects of combat trauma, their names reflecting their reduction to singular symptoms: The Pain, The Fear, The End, The Fury, The Sorrow. They’ve become walking DSM-V criteria, PTSD so totalizing it replaces personhood.

The Cobra Unit still maintains traces of identity beyond battlefield roles. They have histories, relationships, memories of who they were. But already consumption has begun. By Metal Gear Solid 4, the Beauty and Beast Unit has lost even names. Laughing Octopus fragments because singular self couldn’t survive. Raging Raven explodes outward, anger seeking decomposition elsewhere. Crying Wolf freezes in permanent grief. Screaming Mantis controls others because she cannot control herself.

Even defeated non-lethally, they scream their singular: purpose, name, and symptomology before evaporating. Without trauma-function, nothing remains. Remove rage from Raging Raven and she literally ceases to exist. The person from before has been completely consumed. They represent what happens when trauma becomes identity, when warfare colonizes consciousness so thoroughly that alternative ways of being become impossible.

Joseph Campbell’s work on the monomyth provides another lens for understanding Metal Gear’s villains—they’re heroes who got stuck at specific points on their journey and crystallized there. Campbell observed that villains often represent arrested development within the hero’s journey, characters who couldn’t move past a particular trial or threshold. Screenwriters have built entire franchises on this principle: the villain who couldn’t leave the underworld, the mentor who became addicted to power instead of passing it on, the hero who reached apotheosis but refused to return with the elixir.

The Cobra Unit exemplifies this perfectly—each member frozen at their moment of greatest trial during World War II, unable to complete their return journey. They achieved supernatural abilities (the boon) but never integrated these gifts back into normal life. Instead of completing the cycle, they became permanent residents of the extraordinary world, their refusal to return transforming them from potential heroes into obstacles for the next generation. The Beauty and Beast Unit takes this further—they’re not even stuck at a heroic moment but trapped in pure trauma response, their journey so thoroughly interrupted they can’t remember what quest they were on. This reading reveals Kojima’s deeper insight: in war, everyone begins as the hero of their own story, but the machine of conflict prevents anyone from completing their journey, leaving battlefields littered with broken heroes who become the next generation’s demons.

Ocelot: The Metamodern Process Incarnate

Ocelot stands apart from other villains because he isn’t defined by singular trauma. While others become frozen in specific responses, Ocelot IS the process of historical change itself. He doesn’t serve Big Boss so much as recognize in him pure revolutionary potential. Ocelot wants nothing except to work for the purest forces at any moment, creating conflict and relationships between conflicting elements.

He understands that deep states sow seeds of their own destruction, that hierarchies get torn apart by their own rules, that no structure can stand permanently. Ocelot doesn’t relate to ends but embodies process itself. He is the blurring of lines, the oscillation happening in real time. His cowboy persona isn’t aesthetic but philosophical: the gunslinger exists only in the moment of draw, in the space where all possibilities remain open.

When Ocelot becomes Liquid through arm transplantation and self-hypnosis, this apparently silly plot device reveals something profound. He doesn’t become possessed; he chooses possession as tool. He realizes the world needs a Liquid based on its own mechanics, so he becomes one. Kojima’s bizarre understanding of psychotherapy (where therapy can rewrite identity like reprogramming computers) becomes weapon against systems using such tools for control. The supernatural, technological, and psychological merge, revealing all three as aspects of the same phenomenon.

The Pentagon of Power’s Digital Evolution

By Metal Gear Solid 4, war has become the economy itself. Private military companies regulate battlefield emotions through nanomachines. Soldiers’ neurochemistry becomes corporate property.

This represents warfare’s enshittification. Giant organizations justify their existence as inevitable even when hurting everyone including themselves. The Patriots’ AI system epitomizes this: so complex no human understands it, perpetuating itself because stopping would mean admitting the entire structure serves no purpose except continuation.

Kojima shows how totalitarian states, while representing humanity’s worst aspirations, remain limited by their creators’ imaginations. Future brings worse horrors than past could conceive. The series traces evolution from comprehensible nuclear terror to systems where rules and rulers become unknowable. Control embeds in AIs we cannot see yet must interact with. These systems pollute consciousness itself until we may not know who we are or what we’re doing.

Every deep state eventually consumes itself. Growth requires delegation, delegation requires trust, trust creates vulnerability, vulnerability demands control, control requires growth. The cycle continues until collapse, replaced by something worse that learned from previous failure without understanding the fundamental error: attempting to control consciousness itself.

Venom Snake: The Algorithmic Human

Creating Venom Snake represents Big Boss’s most evil act, transcending simple betrayal. Big Boss benefits from a largely imagined awful legacy, then strips a medic of identity to turn that reputation into an actual person. He makes beliefs about himself real, creating the worst parts of his legacy as flesh in this last entry that paradoxically covers the series’ earliest period.

This anticipates how algorithms would detect and recreate everyone as their worst selves, weaponizing network weaknesses. The medic doesn’t just lose identity; he becomes living embodiment of Big Boss’s most violent mythology. Legends that may have been exaggerated become literally true through Venom’s actions. He doesn’t replicate Big Boss; he manifests the darkest interpretation.

Venom Snake is the first algorithmically generated human, created through psychological manipulation rather than code to embody what the system needs Big Boss to be. A human deepfake performing the monster role so the real Big Boss pursues goals undetected. This process mirrors how social media algorithms amplify worst impulses, how surveillance capitalism commodifies anxieties, how we become reduced to our most exploitable characteristics.

The Phantom Chapter: Reality’s Complete Dissolution

If leaked scripts and development documents are accurate, Metal Gear Solid V’s missing chapter—”Peace”—would have pushed beyond narrative incompleteness into complete epistemological breakdown. The revelation wouldn’t just be that you’re playing as Venom Snake, a body double, but that even Venom’s experiences themselves were potentially hallucinatory—products of hypnosis interacting with the metal fragment lodged against his optic nerve.

This creates layers of unreality: you’re not just playing someone who doesn’t know they’re fake, but experiencing the hallucinations of a fake person having fake experiences. The repetitive missions, the déjà vu structure, the cassette tapes that might be hypnotic programming rather than historical record—all pointing toward meaning’s complete dissolution. Every relationship Venom forms, every mission he completes, every emotion he feels could be programmed response to stimuli that never existed.

The metal fragment pressing on the optic nerve becomes perfect metaphor for our current moment. Perception compromised at the hardware level. Not just unreliable narration but the impossibility of narration itself. How do you tell a story when every layer might be simulation, when the simulation itself might be simulated, when even your awareness of simulation could be simulated?

This prescience feels almost prophetic now. We live in an era where deepfakes make video evidence unreliable, where AI generates indistinguishable text, where “alternative facts” create incompatible realities with no arbitrator of truth. Social media bubbles create mutually exclusive worldviews. The complete breakdown of shared epistemological frameworks that Kojima anticipated has arrived. The phantom pain isn’t just missing limbs or stolen identity—it’s the ache of living without stable truth, grief for reality we can no longer verify.

The joke about Metal Gear games being “10 years ahead of their time” suggests 2025 is when MGS5’s themes fully manifest. Looking at our information environment—where AI makes all text suspect, where competing realities can’t agree on basic facts, where identity becomes algorithmic performance—we’re living in the phantom pain. Every person online potentially a bot, every video potentially fake, every memory potentially implanted by engagement algorithms optimizing for reactions we don’t understand.

Gameplay as Moral Architecture

These games explore killing’s inevitability while mechanically discouraging it. Every system rewards mercy: better rankings for non-lethal play, tranquilizer guns with superior range, boss stamina depleting faster without killing, exclusive gameplay options for pacifists.

You fall in love with soldiers you’re evading. Soviet guards discuss being confused about fighting Americans, their World War II allies. They talk about families, fears, dreams. In Metal Gear Solid 3, stomachs rumble when hungry. You can poison food or let them eat peacefully. Every mechanic pushes recognition of enemies as humans with biological needs and emotional lives.

The Sorrow boss fight literalizes this moral architecture. You cannot fight, only accept what you’ve done. The game forces you to wade through everyone you killed. Non-lethal players find an empty river. Killers face endless accusations. Unlike games presenting faceless NPCs as fodder, Metal Gear makes you think about violence while participating in it, forcing contemplation of what you’re doing, making you think about life itself.

Konami’s Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Metal Gear Solid predicted its own demise. When MGS4 was made, monopolistic incentives led Sony to subsidize the ultimate PS3 exclusive through enormous cash investments. Games were still products, complete experiences rather than engagement platforms.

By MGS5, that world had vanished. The industry transformed, trying only to addict players to the cheapest builds possible. It gamified gaming itself, cutting everything entertaining to create addiction, covering everything in microtransactions. Developers no longer wanted elaborate single-player games because incomplete engagement loops proved more profitable.

Kojima had warned about this through his narratives. The Patriots’ AI reducing human experience to exploitable data, the war economy turning conflict into product, nanomachine society commodifying emotions, all predicted mobile gaming’s destruction of traditional development. Kojima and Konami played out the exact scenario Metal Gear documented: deep state eating itself, system consuming its most valuable assets because it only understands extraction.

MGS5 has no ending not just because Kojima was fired but because the industry transformed into something unable to support complete narratives. The missing chapter about Eli, unresolved plots, mission repetition replacing new content reflect not one company’s failure but an entire medium’s transformation into extraction machine. The game’s incompleteness becomes its statement. Just as Venom Snake is Big Boss’s phantom, MGS5 is a phantom of what could have been. Absence is the message.

Konami now makes pachinko machines featuring Metal Gear characters, perfect symbol of capitalism reducing meaning to mechanical repetition and random reward. The company that published games about turning humans into machines now literally turns its characters into gambling machines.

The Algorithmic Present Metal Gear Predicted

Venom Snake’s creation anticipated our current algorithmic reconstruction as our worst selves. Social media platforms learn engagement triggers and amplify those traits. We become performed versions optimized for metrics we don’t control. Like Venom, we may not know we’re performing. Authentic selves get overwritten by system needs.

Vocal cord parasites killing language speakers literalize communication weaponization. We self-censor not through command but because expression became dangerous. One wrong word triggers cascading consequences. Parasites represent trauma encoding into communication’s medium, making connection potentially lethal. In our age, words literally destroy lives, careers, communities.

The prescience extends further: the game’s incompleteness, its missing ending about meaning’s breakdown, perfectly captures our current inability to complete narratives or maintain stable truth. We’re all Venom Snake now, performing identities we don’t remember choosing, following programming we can’t access, experiencing reality that might be several layers removed from anything real.

Systems That Exist Only to Exist

Lewis Mumford’s analysis of the pentagon of power (political authority, military force, economic exploitation, technological manipulation, ideological control) reveals systems that have forgotten their original purpose, if they ever had one. They exist now only to perpetuate their own existence, their own ego, their own entropy, their own hierarchies, and their own rules. They seek to justify themselves even when the world—and they themselves—would be better off without them.

The OSS forms during World War Two to gather intelligence against fascism. A noble purpose, perhaps. But it becomes the CIA to help America inherit the imperial project of the Reich it supposedly defeated. Operation Paperclip wasn’t aberration but blueprint—absorbing the enemy’s methods while claiming moral superiority. The soldiers America aided in Afghanistan against the Soviets become the Taliban we fight decades later. The mujahideen we armed become the enemy requiring new arms deals, new contractors, new wars. The reaction to 9/11 creates a surveillance state that later enables algorithmic system surveillance that changes consciousness itself.

These technological progressions differ in form but remain identical in function. Only the sense of crisis changes, the pervasive influence updates its interface. The crisis is always the same crisis wearing new masks. This is how Kojima sees things: not as conspiracy but as pattern, systems creating the problems they claim to solve, deep states manufacturing the chaos they promise to order.

Each iteration learns from the last’s failures without understanding the fundamental error: the attempt to control human consciousness through systems that can only destroy what they claim to protect. The CIA overthrows democratically elected governments to “protect democracy.” The NSA violates privacy to “ensure freedom.” Private military contractors create war to “maintain peace.” The contradiction isn’t bug but feature—systems need enemies to justify themselves, so they create them.

Breaking the Fourth Wall as Ethical Imperative

What began as silly joke in early Metal Gear games—guards seeing your footprints, Psycho Mantis reading your memory card—evolves into ethical project by the series’ end. The fourth wall breaking stops being clever and becomes necessary, forcing recognition that games aren’t separate from life but shape it fundamentally.

Children and adults alike emulate games they play. It changes how we talk, the metaphors we make, how we interact with the world. When I was in third grade, I would run like Sonic the Hedgehog, arms swept back, believing it made me faster. After binge-playing Metal Gear Solid, I sometimes find myself ducking around corners to peek at something, checking sightlines that don’t matter in reality but have been programmed into my movement patterns. The rules of virtual worlds bleed into our heads, restructuring how we navigate physical space.

This bleeding is precisely Kojima’s point. We are part of systems we only partially understand, performing behaviors we didn’t consciously choose, following rules we never agreed to. When Snake tells you to turn off the console, when the Colonel’s skull appears beneath his face, when the game crashes and pretends to delete your saves—these moments force recognition of how deeply embedded we are in systems beyond our perception.

The genius of Kojima’s direction lies in understanding the subconscious and its connection to a larger collective unconscious responsible for most of the world the characters can’t see. The Patriots aren’t metaphor for shadow government—they’re literalization of how power actually works, through systems so complex no individual comprehends them, through influences so pervasive we mistake them for reality itself.

Redemption Through Recognition

The transcendent moments where characters achieve redemption or salvation in these games occur when they’re able to see these influences, accept them, and integrate them. They understand their motivations aren’t their own and others’ motivations as extensions of greater systems. The Boss sees this but can only express it spiritually. Big Boss never sees it, trying to build her vision through force. Zero sees it but thinks he can control it through information. Solid Snake sees it and chooses to break the cycle by refusing to reproduce it.

Only Ocelot truly gets it, which is why he’s simultaneously the most evil and most free character. He doesn’t resist the system or serve it—he becomes it, flowing with its currents while maintaining enough consciousness to steer slightly. He understands you can’t fight the Pentagon of Power from outside because there is no outside. You can only introduce small variations that compound over time.

This is why Venom Snake represents ultimate horror: someone who doesn’t even know they’re performing, who mistakes programmed responses for authentic choice. He embodies our current predicament, where algorithms detect our patterns and feed them back to us until we can’t distinguish between our desires and the system’s needs. And if the missing chapter’s implications are real, even that performance might be hallucination—phantom pain all the way down.

Sloterdijk’s Spheres, Bubbles, and Foam

Peter Sloterdijk’s spheres provide the philosophical framework for understanding Metal Gear’s world. Human civilization began in spheres—complete worldviews where everyone shared the same metaphysical bubble. Medieval Christendom, Imperial China, Indigenous cosmologies—these were spheres where meaning was total and encompassing. God was above, Hell below, Earth between. Everyone knew their place in the cosmic order.

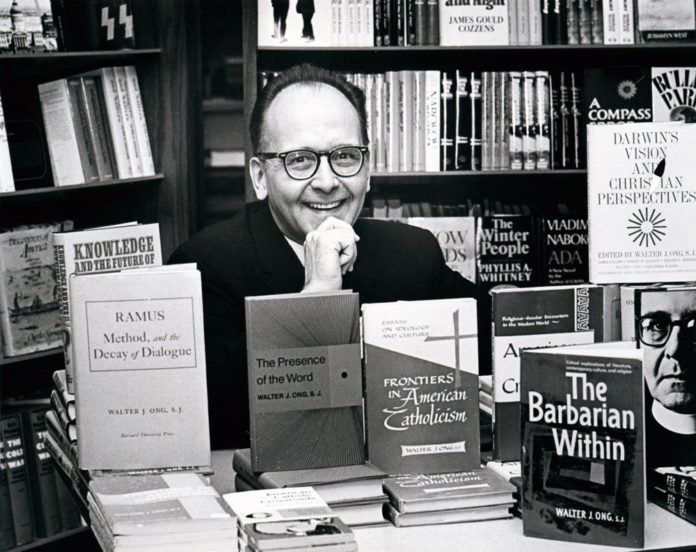

The printing press shattered spheres into bubbles. Information could travel between worldviews, contaminating pure ideologies with foreign ideas. The Reformation happens because people can read the Bible themselves. Science emerges because observations can be shared across distances. Bubbles still maintain internal coherence but must account for other bubbles existing. The colonial period is bubbles colliding, each trying to impose its internal logic on others.

Modernity accelerates this into foam—countless tiny bubbles pressing against each other, taking shape only through mutual pressure, no overarching structure remaining. We live in foam now, each person a bubble, our shape determined by the bubbles pressing against us. Social media makes this visible: millions of individual reality-bubbles, incompatible yet interdependent, creating structure through collision rather than design.

Metal Gear Solid documents this transition. The Boss lived in a sphere—she could imagine unified world because she remembered when worldviews were total. Big Boss lived during the bubble-to-foam transition, trying to create new spheres (Outer Heaven, Zanzibar Land) while the world fragmenting made this impossible. Solid Snake exists in foam, no grand narrative available, only local interactions between incompatible realities. Raiden embodies the foam-born generation, never knowing anything but fragments, assembling identity from debris.

The Patriots represent the attempt to create artificial sphere through information control, to reimpose total worldview on foam reality. But foam can’t become sphere again. It can only compress into more complex foam structures. The AI system they build to manage this complexity becomes another layer of foam, more bubbles pressing against existing bubbles, the structure growing more unstable with each attempt at control.

The Collective Unconscious Made Visible

Kojima understands that the collective unconscious isn’t mystical concept but observable phenomenon. When millions play the same game, they share psychological architecture. When everyone checks their phone every few minutes, they’re synchronized to invisible rhythm. When TikTok dances spread globally in days, we’re watching the collective unconscious update in real-time.

The codec conversations in Metal Gear make this literal—voices in your head that aren’t yours, instructions you follow without questioning their source. The Patriots’ control through information manipulation isn’t fiction but documentary. We already live in their world, our thoughts shaped by algorithms we’ll never see, our emotions regulated by engagement metrics, our relationships mediated by platforms optimizing for addiction rather than connection.

What makes Metal Gear prophetic isn’t predicting specific technologies but understanding the pattern: every system created to solve a problem becomes the problem requiring the next system. The War on Terror creates more terrorists. Surveillance to ensure safety creates paranoia requiring more surveillance. Social media to connect people creates isolation requiring more social media. The Pentagon of Power doesn’t solve—it perpetuates, because solving would mean admitting it’s unnecessary.

The Crisis That Never Ends

The crisis is always the same crisis because crisis is what these systems produce. Without emergency, there’s no justification for emergency powers. Without threat, there’s no need for protection. Without enemy, there’s no purpose for the military-industrial complex. So the system creates what it needs: terrorists where there were none, threats where there was peace, enemies where there were neighbors.

Metal Gear Solid 5’s missing ending is perfect because these systems never end. They just transform, upgrade, metastasize. The War to End All Wars becomes World War II becomes Cold War becomes War on Terror becomes whatever we’re calling it now. The names change but the structure remains: crisis justifying control justifying behavior creating crisis.

Kojima saw this clearly: the Pentagon of Power exists only to ensure the Pentagon of Power continues existing. It has no goal beyond its own perpetuation, no purpose beyond its own justification, no meaning beyond its own continuation. It’s capitalism as pure entropy, consuming everything to produce nothing except the need for more consumption.

The only escape Kojima offers isn’t escape at all but recognition. See the systems. Name them. Understand you’re part of them. Know your thoughts aren’t entirely your own. Recognize the phantom pain of missing authenticity. And then, like Snake, choose what to pass on and what to let die with you. The cycle can’t be broken from outside because there is no outside. But it can be interrupted from within by those who see it clearly enough to refuse their role in its continuation.

This is why Metal Gear matters: not as entertainment but as diagnosis, not as game but as mirror, not as fiction but as the most accurate documentary of how power actually works in the metamodern age—through systems no one controls, serving purposes no one remembers, creating crises no one can solve, perpetuating themselves through our inability to imagine their absence.

The Metamodern Oscillation

The MSG series documents the historical transition from modernity’s grand narratives through postmodernity’s fragmentation into metamodernism’s endless oscillation. We’re pulled between modernism’s certainties and postmodern dissolution where no meaning is possible. We cannot synthesize these positions, cannot find stable ground, cannot stop the pendulum.

Big Boss and The Boss represent the last generation believing in modernist solutions. Their attempts to preserve or transcend these structures created postmodernism’s conditions. Solid Snake exists in the postmodern moment, everything deconstructed, meaning suspect. Raiden embodies metamodern condition, oscillating between believing simulation and knowing it’s fake, never settling.

Ocelot transcends by becoming oscillation itself. He doesn’t believe positions but moves between them. He serves Big Boss, Patriots, himself, chaos, order, all and none simultaneously. He understands process is all that exists, oscillation has replaced positions themselves.

The Fusion That Cannot Hold

The fusion of bodies, psyches, identities, and networked consciousness reveals we’re part of systems we neither perceive nor escape. Characters merge, split, impersonate, steal faces, voices, memories. Boundaries between self/other, human/machine, reality/simulation reveal themselves as always-false illusions maintained through collective pretense.

This isn’t science fiction but documentary. We live in networked consciousness, thoughts shaped by algorithms, emotions regulated pharmaceutically, memories stored in clouds. The difference between Snake’s codec and smartphones is degree not kind. Patriots’ information control seems quaint compared to surveillance capitalism. MGS4’s nanomachine society understates technology’s colonization of experience.

Kojima asks whether humanity can save itself. Will anything come after the metamodern? Can we synthesize Sloterdijk’s broken spheres? The series suggests we’re trapped in permanent oscillation, but oscillation itself might keep us human. The struggle for meaning, knowing meaning’s impossibility, might be the only meaning remaining.

Snake’s final message to live for future not nations or ideologies isn’t hope or despair but metamodern acceptance. We know the game’s rigged but play anyway because not playing is defeat. We cannot escape trauma cycles but can minimize transmitted damage. We cannot heal systematic wounds but can name them. In naming phantom pain, we retain humanity in an inhuman world.

The ultimate prescience of MGS5—if its missing chapter truly explored reality’s complete breakdown through layers of hallucination—is that even this analysis could be wrong. Maybe the leaked scripts are fake. Maybe our interpretation is programmed. Maybe the real message is that there is no message, just endless oscillation between meaning and meaninglessness, forever approaching truth we can never verify. That’s the real phantom pain: not the absence of something that was there, but the presence of something that might never have existed at all.

0 Comments