The Radical Pantheism of Amalric of Bena

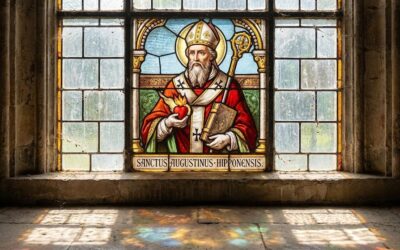

In the constellation of medieval mystics, few stars burned as brightly—or were extinguished as violently—as Amalric of Bena (died c. 1205). A theologian at the University of Paris, Amalric proposed a vision of God so radical that it led to the exhumation and burning of his bones five years after his death. His crime was Pantheism: the belief that “God is All.”

For the modern depth psychologist, Amalric is not a heretic but a pioneer. He anticipated the Jungian realization that the Self is not an external authority but an internal reality. His teaching that “every Christian is a member of Christ” was not a metaphor for him, but a literal, psychological fact. This aligns with the Ego-Self Axis, suggesting that the core of the human personality is, in essence, divine.

Biography & Timeline: Amalric of Bena (c. 1150–1205)

Amalric was born in the village of Bena, near Chartres, France. He rose to prominence as a master of theology at the University of Paris, where he captivated students with his blend of Neoplatonism and Christian mysticism. Unlike the dry scholastics of his day, Amalric taught that the Age of the Spirit was at hand—a time when external sacraments would be replaced by direct inner knowledge (Gnosis).

His teachings sparked a movement known as the Amalricians, who believed that because the Holy Spirit resided within them, they were incapable of sin. This radical antinomianism terrified the Church. In 1210, a synod in Paris condemned his teachings, burned ten of his followers at the stake, and scattered his ashes in unconsecrated ground.

Key Milestones in the Legacy of Amalric

| Year | Event / Publication |

| c. 1150 | Born in Bena, France. |

| c. 1200 | Teaches at the University of Paris, formulating his pantheistic theology. |

| 1204 | Summoned to Rome by Pope Innocent III to answer for his “erroneous” doctrines. |

| 1205 | Dies in Paris, reportedly recanting his views on his deathbed (though his followers continued). |

| 1210 | Posthumously condemned; his body is exhumed and thrown into a field. |

Major Concepts: The Three Ages of the Spirit

The Incarnation of the Divine in All

Amalric’s central thesis was that “God is the essence of all creatures.” This shattered the medieval barrier between Creator and Creation. Psychologically, this mirrors the concept of the Self in Jungian psychology—the organizing principle of the psyche that is both personal and transpersonal.

The Three Epochs

Amalric, influenced by Joachim of Fiore, taught a trinitarian view of history:

- Age of the Father (Old Testament): Characterized by law and fear.

- Age of the Son (New Testament): Characterized by faith and the church hierarchy.

- Age of the Spirit (The Present/Future): Characterized by love and direct knowledge.

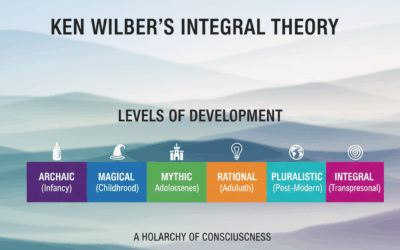

In this final age, Amalric argued, the external church would become obsolete because every individual would be a “Christ.” This is a profound metaphor for the goal of individuation—the movement from relying on external authority (the Father) to finding the internal authority of the Spirit.

The Conceptualization of Trauma: The Exile from God

If God is the essence of the soul, then trauma is the **forgetting** of this essence. Amalric viewed sin not as a moral failure, but as a state of ignorance—a failure to recognize one’s own divinity. This is remarkably close to the Gnostic view of the human condition.

In trauma therapy, patients often feel “damned” or fundamentally broken. The Amalrician perspective suggests that this brokenness is an illusion caused by the ego’s separation from its source. Healing involves a “return” to the realization that the core of the self remains untouched by trauma.

Furthermore, the persecution of the Amalricians highlights the trauma of the **visionary**. When an individual’s inner experience contradicts the collective’s outer rules, a severe psychic split occurs. This is the trauma of the heretic—the pain of holding a truth that society calls madness.

Lasting Influence: The Underground River

Though the Church tried to erase him, Amalric’s ideas survived. They flowed into the Free Spirit movement, the Rhineland Mystics (like Eckhart), and eventually into the Reformation. Today, they resurface in Transpersonal Psychology and the work of Stanislav Grof, who validates the experience of “Cosmic Consciousness.”

Amalric reminds us that the psyche is vast, dangerous, and divine. To explore it is to risk heresy, but it is also the only way to find the “Holy Spirit” within.

Further Reading & Resources

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Amalricians.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Medieval Mysticism.

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Amalric of Bena.

0 Comments