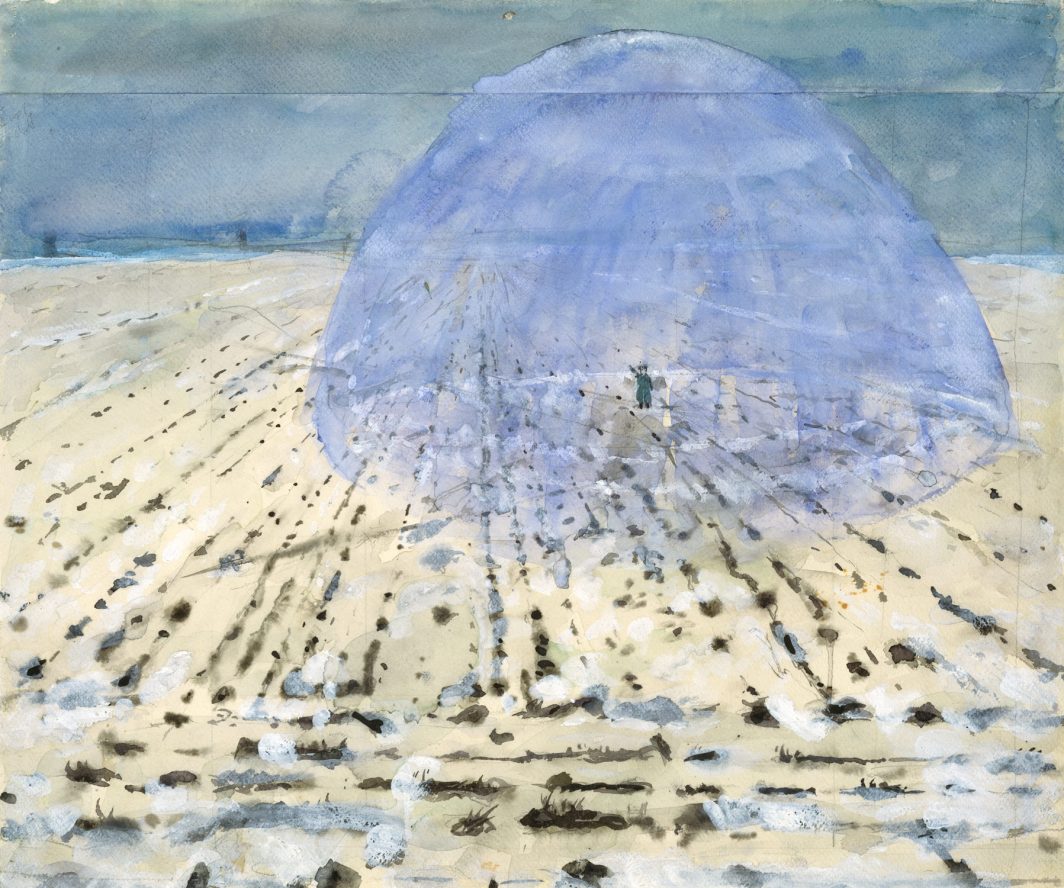

1970 – Everyone stands under his own dome of heaven – Anselm Kiefer

According to Kiefer, each person has their own blue “dome of heaven” and everyone has their own God that they believe in.

Game of Spheres

Key Points:

1. The metamodern era is characterized by an oscillation between modernist faith and postmodern doubt, driven by factors such as hyperindividualism, information overload, erosion of expertise, and a crisis of meaning.

2. Transformative gameplay, grounded in the post-secular sacred, offers a potential path for navigating the complexities of the metamodern age by engaging the whole person and promoting personal and social transformation.

3. The metamodern oscillation bears similarities to Carl Jung’s concept of the “tension of opposites,” emphasizing the need to hold contradictory forces in balance for psychological growth.

4. The post-secular sacred affirms the reality of the numinous and the transcendent dimension of human experience while acknowledging the contingency of all beliefs.

5. Transformative gameplay can help cultivate an integrative intelligence that balances the rational and the intuitive, the head and the heart, by immersing players in symbolic worlds and archetypal narratives.

6. The metamodern challenge is to transcend the narrow, ego-driven understanding of the self and situate oneself within a greater project that extends beyond individual lives and immediate market demands.

7. Transformative gameplay can serve as a means of existential and ethical experimentation, allowing players to rehearse different roles, perspectives, and narratives in the “great improv of life.”

8. The process of transformative gameplay is not without challenges and dangers, such as the risk of escapism, dogmatism, or using the language of the sacred to mask egoic agendas.

9. If approached with humility, discernment, and a commitment to growth and service, transformative gameplay can be a powerful ally in the metamodern quest for meaning and purpose.

10. The metamodern moment presents an opportunity for spiritual growth and creative transformation by tapping into the power of sacred play and weaving a new mythology for our time.

We have to speak of space because humans are themselves an effect of the space they create. Human evolution can only be understood if we also bear in mind the mystery of insulation/island-making [Insulierungsgeheimsis] that so defines the emergence of humans: Humans are pets that have domesticated themselves in the incubators of early cultures. All the generations before us were aware that you never camp outside in nature. The camps of man’s ancestors, dating back over a million years, already indicated that they were distancing themselves from their surroundings.

– PETER SLOTERDIJK

From Classicism to Metamodernism

Throughout history, Western culture has been shaped by a series of dominant paradigms that structured people’s understanding of reality, values, and aesthetics. The Classical era, lasting from antiquity through the 18th century, was defined by ideals of order, harmony, and rationality. Classicism gave way to Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as rapid industrialization, scientific advances, and social upheaval led to a celebration of progress, individualism, and grand utopian visions.

However, the catastrophic wars and genocides of the 20th century shattered modernist optimism, ushering in the Postmodern age. Postmodernism was marked by a skepticism towards overarching metanarratives and claims of objective truth. It emphasised relativism, irony, and the constructed nature of meaning. Postmodern thinkers deconstructed modernist assumptions, exposing the ways power and bias shape our discourses.

Now, as we move deeper into the 21st century, the postmodern paradigm itself is beginning to unravel. Several key issues are contributing to postmodernism’s breakdown and the emergence of a new structure of feeling some have labeled metamodernism. The philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s concept of oscillation is central to understanding this transition.

For Sloterdijk, the defining feature of the metamodern era is a constant oscillation between postmodern irony and modern sincerity, between constructivist relativism and essentialist universalism. Whereas modernism was defined by a naive belief in progress and objective truth, and postmodernism by a cynical rejection of all metanarratives, metamodernism is characterized by an ironic sincerity that acknowledges the failures of both while refusing to abandon the possibility of meaning altogether.

This oscillatory movement is driven by several factors pushing postmodernism to its breaking point:

Hyperindividualism:

Postmodern critiques of power, combined with neoliberal economics and digital technologies, have produced a radically individualistic culture. Traditional sources of meaning and social bonds have eroded. In their absence, individuals must craft identities from a dizzying bricolage of signs detached from stable referents. This untethered individualism often results in alienation, anxiety, and a yearning for sincere connection that postmodern irony cannot satisfy.

Information overload:

We are bombarded by an unprecedented torrent of often contradictory facts, opinions, and narratives in the digital age. This informational cacophony makes it increasingly difficult to sort truth from falsehood, important signals from trivial noise. Paradoxically, the proliferation of knowledge has led not to greater clarity but to deepening uncertainty, spurring a desire for coherent frameworks of meaning.

Erosion of expertise:

One consequence of this confusion is a profound erosion of trust in traditional authorities and experts, from doctors and scientists to journalists and academics. As postmodernists revealed, expert discourses are shaped by biases and power dynamics. In an increasingly complex world, lay people struggle to navigate conflicting expert opinions, opening space for conspiracy theories and “alternative facts” to flourish.

Crisis of meaning:

Taken together, these forces have plunged us into a crisis of meaning. We lack shared myths sturdy enough to orient us in a chaotic, ever-shifting reality. The irony and relativism of postmodernism offer little guidance for rebuilding a framework of purpose. Many feel cast adrift, nostalgic for the certainty of premodern worldviews while recognizing there is no going back.

It is out of this postmodern crucible that metamodernism emerges, not as a stable synthesis but as a constant oscillation between modern faith and postmodern doubt, universalism and relativism, sincerity and irony. For Sloterdijk, this oscillation is not a weakness but a defining feature of the metamodern sensibility – an attempt to navigate the crisis of meaning without recourse to either modernist naivete or postmodern cynicism.

The metamodern subject remains suspended between worlds, yearning for truth while acknowledging its contingency, striving for authentic connection while recognizing the mediated nature of all relationships in a hyperconnected age. This oscillation permeates contemporary culture, from the ironic sincerity of metamodern art and media to the “post-truth” landscape of political discourse.

In the analysis that follows, we will explore this nascent metamodern paradigm in more depth, tracing its expressions across culture, politics, and philosophy. We will consider how metamodernism might answer the existential challenges of a fragmented postmodern world – and what perils it must navigate on the path ahead. At the heart of this exploration will be Sloterdijk’s concept of oscillation as the defining motion of a paradigm caught between the modern and the postmodern, between the desire for meaning and the knowledge of its ultimate contingency.

Transformative Gameplay and the Post-Secular Sacred in the Age of Metamodernity

As we navigate the complexities of the metamodern age, marked by the constant oscillation between modernist faith and postmodern doubt, the need for new frameworks to create meaning and guide action becomes increasingly apparent. The post-secular sacred, as explored through the lens of transformative gameplay, offers a potential path forward – a way to sit with the tensions of our time without succumbing to either naive certainty or nihilistic despair.

The metamodern oscillation between irony and sincerity, relativism and universalism, bears a striking resemblance to psychologist Carl Jung’s concept of the “tension of opposites.” For Jung, the psyche is not a unified whole but a dynamic system of contrasting forces – conscious and unconscious, masculine and feminine, individual and collective. It is only by holding these opposites in tension, resisting the urge to collapse into one pole or the other, that genuine psychological growth becomes possible.

Similarly, the metamodern sensibility calls us to embrace the tension between the modern and the postmodern – to acknowledge the limits of our knowledge while still reaching for a greater spiritual purpose that lies beyond the grasp of pure reason. This is the essence of the post-secular sacred: a religiosity that recognizes the contingency of all beliefs while still affirming the reality of the numinous, the transcendent dimension of human experience.

Transformative gameplay offers a powerful tool for cultivating this post-secular sensibility. By creating immersive, interactive experiences that engage the whole person – body, mind, and spirit – such games can help players navigate the complexities of the metamodern world without losing sight of the sacred. They can serve as filters for the overwhelming flood of information, helping players discern signal from noise and develop new forms of expertise grounded in embodied wisdom rather than abstract knowledge.

For too long, we have relied on the wrong cognitive faculties to guide us through the challenges of modernity. In politics, we have built empires on the shaky foundations of ego and emotion, casting ourselves as victims or saviors in a Manichean struggle between good and evil. In science, we have sought to master the external world through instrumental reason, neglecting the inner dimensions of consciousness and meaning.

The metamodern turn calls us to a different way of knowing – one that balances the head and the heart, the rational and the intuitive. Transformative gameplay can help us cultivate this integrative intelligence by immersing us in symbolic worlds that speak to both the intellect and the soul. By grappling with archetypal themes and mythic narratives, players can access deeper levels of insight and inspiration than those available to the discursive mind alone.

This is not to suggest that transformative gameplay is a panacea for the ills of the metamodern age. The oscillation between faith and doubt, hope and despair, is not something that can be overcome through any single practice or technology. But by creating spaces for sacred play – for the imaginative exploration of meaning in a disenchanted world – such games can help us cultivate the spiritual resilience needed to navigate the challenges ahead.

Ultimately, the goal of transformative gameplay in the age of metamodernity is not to provide final answers or fixed truths, but to help us ask better questions and live more deeply into the mystery of existence. In a world of information overload and existential uncertainty, it is only by embracing the tension of opposites – the paradoxical play of light and shadow, knowing and unknowing – that we can hope to chart a course towards greater wisdom, compassion, and holistic flourishing.

As we design and play such games, we must remain mindful of their limitations and potential pitfalls. The post-secular sacred is not immune to the distortions of ego and ideology, and the very technologies that enable transformative gameplay can also be used for manipulation and control. We must approach this work with humility and discernment, always questioning our assumptions and staying open to the unexpected.

Yet for all the challenges it poses, the metamodern moment also presents an unprecedented opportunity for spiritual growth and creative transformation. By tapping into the power of sacred play, we can begin to weave a new mythology for our time – one that honors the past without being bound by it, and faces the future with courage and an open heart. In doing so, we may just discover that the oscillations of the metamodern soul are not a barrier to meaning, but the very ground from which it springs.

Transcending the Ego: Situating the Self in a Greater Project

One of the central challenges of the metamodern age is the hyperindividualism and short-sightedness fostered by the combination of neoliberal economics, digital technologies, and postmodern relativism. In this context, the self is often reduced to the narrow confines of the ego – a fragile, isolated entity driven by the pursuit of immediate gratification, competitive advantage, and self-aggrandizement.

However, as the existential philosopher Martin Heidegger argued, this understanding of the self is fundamentally incomplete and inauthentic. For Heidegger, the self is not an isolated ego but a “being-in-the-world” – a relational, situated, and temporal entity whose identity is shaped by its engagement with others, its cultural and historical context, and its orientation towards the future.

From this perspective, the hypercompetitive individualism of the market and the fleeting satisfactions of the ego are revealed as deeply inadequate responses to the human condition. They may provide a sense of momentary validation or success, but they ultimately leave us alienated, anxious, and adrift in a world without inherent meaning or purpose.

The metamodern challenge, then, is to transcend this narrow, ego-driven understanding of the self and to situate ourselves within a greater project – one that extends beyond the limits of our individual lives and the immediate demands of the market. This is where the oscillation between modernist faith and postmodern doubt, between the desire for meaning and the recognition of its ultimate contingency, comes into play.

On the one hand, the metamodern sensibility recognizes the postmodern insight that all grand narratives and universal truths are ultimately constructed, contingent, and open to critique. We cannot simply retreat into the false certainties of tradition or the naive optimism of modernity, nor can we find lasting fulfillment in the shallow consumerism and self-absorption of the present moment.

On the other hand, the metamodern sensibility also recognizes the human need for meaning, purpose, and connection – for a sense of being part of something greater than ourselves. We may not be able to access absolute truth or certainty, but we can still strive to create meaningful narratives, communities, and projects that give shape and direction to our lives.

This is the paradox and the promise of the metamodern moment: to live in this time but not for this time, to embrace the tensions and uncertainties of the present while also orienting ourselves towards a future that is yet to be created. It is a call to situate ourselves within a larger story, to see our lives as part of an unfolding process of cultural and cosmic evolution, even as we acknowledge the ultimate mystery and contingency of that process.

Transformative gameplay, grounded in the post-secular sacred, offers a powerful tool for cultivating this expanded, situated sense of self. By immersing us in symbolic worlds that evoke archetypal themes and existential questions, such games can help us to see beyond the narrow confines of the ego and to connect with the deeper, more enduring aspects of our being.

Through the oscillation of the metamodern – the constant play between immersion and reflection, between identification and distance – transformative games can create a space of creative tension and possibility. They can challenge us to confront the limitations of our current identities and worldviews, while also inviting us to imagine and enact new ways of being and relating.

In this sense, transformative gameplay is not just a form of entertainment or escapism, but a means of existential and ethical experimentation – a way of rehearsing for the great improv of life. By playing with different roles, perspectives, and narratives, we can begin to see ourselves as more than just isolated egos or passive consumers, but as creative agents and co-creators of a larger, more meaningful story.

Of course, this process is not without its challenges and dangers. As with any form of transformative practice, there is always the risk of getting lost in the play, of confusing the game with reality, or of using it as a way to avoid the difficult work of living and relating in the actual world. There is also the danger of falling into new forms of dogmatism, elitism, or escapism, of using the language of the sacred to justify or mask our own egoic agendas.

But if approached with humility, discernment, and a genuine commitment to growth and service, transformative gameplay can be a powerful ally in the metamodern quest for meaning and purpose. By situating ourselves within a greater project, by striving to create beauty, truth, and goodness in the face of uncertainty and impermanence, we can begin to live a life that is not just about us, but about the larger story of which we are a part.

Bibliography:

1. Sloterdijk, P. (2011). Bubbles: Spheres Volume I: Microspherology. Semiotext(e).

2. Jung, C. G. (1969). The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Princeton University Press.

3. Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time. Harper & Row.

4. Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt, Brace & World.

5. Turner, V. (1982). From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. PAJ Publications.

6. Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon Books.

7. Huizinga, J. (1955). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Beacon Press.

8. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

9. McGilchrist, I. (2009). The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press.

10. Taylor, C. (2007). A Secular Age. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

11. Vermeulen, T., & van den Akker, R. (2010). Notes on Metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 2(1).

12. Freinacht, H. (2017). The Listening Society: A Metamodern Guide to Politics, Book One. Metamoderna ApS.

13. Saler, M. (2012). As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Oxford University Press.

14. Koenig, H. G. (2018). Religion and Mental Health: Research and Clinical Applications. Academic Press.

15. Mantovani, F., & Riva, G. (2001). Building a Bridge between Different Scientific Communities: On Sheridan’s Eclectic Ontology of Presence. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 10(5), 537-543.

For those interested in diving deeper into Jung’s own writings, his collected works are available, including seminal texts like “Psychological Types” and “Man and His Symbols.”

The Red Book, Jung’s personal journal of his “confrontation with the unconscious,” provides unique insights into his thought process and the development of his theories.

Works by Jung’s close associates and successors can offer valuable perspectives on analytical psychology:

Marie-Louise von Franz wrote extensively on Jungian psychology, particularly on fairy tales and alchemy.

Edward Edinger explored the process of individuation and the archetypal symbolism in various cultural and religious contexts.

James Hillman developed archetypal psychology, which emphasizes the multiplicity of the psyche.

For those interested in the application of Jungian concepts to mythology and comparative religion, the works of Joseph Campbell are highly recommended.

Contemporary Jungian analysts continue to develop and apply Jung’s ideas in various fields, including psychotherapy, cultural studies, and the arts.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

0 Comments