The Peloponnesian War: History, Psychology, and the Battle Within

The Outer War Mirrors the Inner Conflict of the Psyche

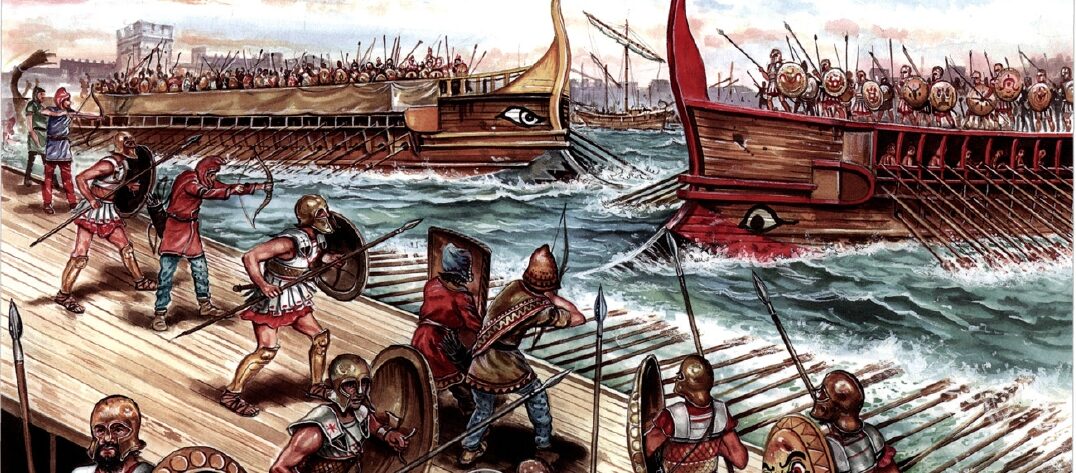

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) was a pivotal conflict in ancient Greek history that reshaped the Hellenic world. But more than just a military struggle between rival city-states Athens and Sparta, this epochal war represents a clash of ideologies and psychologies that is embedded in the human condition itself. By viewing this conflict through the lens of Jungian psychology, we can unpack its deeper symbolic meaning and extract wisdom for our time.

Historical Context: The Greek World in the 5th Century BC

To understand the Peloponnesian War, we must first set the stage of classical Greece. In the aftermath of the Persian Wars (492-449 BC), where an alliance of Greek city-states fended off invasion by the mighty Persian Empire, two powers rose to the fore:

Athens

Located in Attica, Athens was the cultural and intellectual heart of Greece. It was the birthplace of democracy, where all male citizens could vote and serve in public office. Athens was an open, cosmopolitan society that prized the arts, philosophy, and rhetoric. Great thinkers like Socrates and Plato called Athens home.

Sparta

In the Peloponnese peninsula, Sparta stood in stark contrast as a militant society fanatically dedicated to martial excellence. Spartan boys were taken from their families at a young age and underwent a brutal regimen called the agoge to forge them into elite warriors. Sparta was an oligarchy where a small group of landed aristocrats ruled over a population of second-class citizens, freedmen, and slaves.

However, Sparta’s regimented society had a dark side. It was a rigidly stratified, totalitarian regime where a small caste of elite Spartiates ruled over a subjugated population of serfs called helots who handled all the labor. The Spartan system depended on keeping the helots in a state of brutal oppression and terror.

Women, while having more rights than in other Greek city-states, were still second-class citizens valued mainly for producing strong babies. Spartan culture disdained the finer things in life – the arts, philosophy, anything that smacked of softness or sensitivity. It was a militarized ethic that exalted only strength, obedience, endurance, and power.

The Delian League

After the Persian Wars, Athens assumed leadership of the Delian League, an alliance of Greek city-states sworn to defend against future Persian aggression. However, Athens increasingly dominated the League and used its navy to turn allies into tributary subjects, extracting wealth to finance ambitious building projects like the Parthenon.

The Peloponnesian League

Sparta commanded its own alliance, the Peloponnesian League, made up of oligarchic city-states fearful of Athenian power. As tensions rose between Athens and Sparta in the decades following the Persian Wars, their respective alliances became armed camps. War was brewing.

A Jungian Perspective: The War Within

While a military history is illuminating, what makes the Peloponnesian War timelessly fascinating is its psychology. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875-1961) held that all human societies and psyches contain common archetypes, or patterns of behavior and symbolism. By viewing Athens and Sparta as Jungian archetypes in conflict, we see that their war represents the clash between different parts of the psyche:

The Archetypal Adversaries

Athens

Athens is the epitome of Jung’s anima archetype: the unconscious, feminine dimension of the psyche associated with creativity, feeling, and culture. Athenian dynamism and openness reflect the fertility of the unconscious. Athens, however, held these parts of the psyche in balance and also celebrated arts beauty and individuality.

Sparta

Sparta, on the other hand, embodies the “masculine” ego archetype: the conscious, heroic self that seeks to master the world through force and will. Spartan conservatism and austerity parallel how the ego represses and restricts the unconscious.

Pericles Funeral Oration

If then we prefer to meet danger with a light heart but without laborious training, and with a courage which is gained by habit and not enforced by law, are we not greatly the better for it? Since we do not anticipate the pain, although, when the hour comes, we can be as brave as those who never allow themselves to rest; thus our city is equally admirable in peace and in war. For we are lovers of the beautiful in our tastes and our strength lies, in our opinion, not in deliberation and discussion, but that knowledge which is gained by discussion preparatory to action. For we have a peculiar power of thinking before we act, and of acting, too, whereas other men are courageous from ignorance but hesitate upon reflection.

-Pericles Funeral Oration of the Veterans in the Peloponnesian War

The Imbalance of Power

Just as Athenian naval strength let it dominate allies and turn the Delian League into an empire, the rational ego can overpower and subjugate the unconscious. However, this one-sided dynamic is ultimately unstable.

By pursuing grandiose projects and picking needless fights with Sparta, Athens succumbed to an inflated ego that no longer heeded wise counsel. Divorced from unconscious wisdom, it self-destructed.

Similarly, a Spartan victory did not bring lasting peace because it was predicated on keeping the Athenian anima muzzled. The Spartan ego could not integrate the energies of its opposite.

“Since you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

– Melian Dialogue In Thucydides

Sparta’s Pyrrhic Victory: The Failure to Integrate the Athenian Anima

While Sparta ultimately emerged victorious in the Peloponnesian War, this triumph did not bring the lasting peace and stability that might have been expected. From a Jungian perspective, this failure can be attributed to Sparta’s inability to integrate the qualities represented by Athens – the anima archetype. The Spartan ego, so long defined by its opposition to Athenian values, could not adapt to a post-war world that required a synthesis of both city-states’ strengths.

Examples of Sparta’s Failure to Integrate:

- Cultural Stagnation:

- Sparta maintained its rigid, militaristic society even after the war’s end.

- Example: While Athens had fostered philosophy, drama, and the arts, Sparta continued to discourage intellectual pursuits. This cultural inflexibility left Sparta ill-equipped to lead a diverse Greek world.

- Diplomatic Ineptitude:

- Sparta’s straightforward, often brutish diplomacy contrasted sharply with Athenian finesse.

- Example: In dealing with former Athenian allies, Sparta often resorted to force rather than negotiation, alienating potential supporters and fostering resentment.

- Suppression of Democracy:

- Instead of incorporating elements of Athenian democracy, Sparta imposed oligarchies on conquered territories.

- Example: In Athens itself, Sparta installed the Thirty Tyrants, a brutal oligarchic regime that was quickly overthrown, demonstrating Sparta’s failure to understand and integrate democratic principles.

- Lack of Inclusive Citizenship:

- Sparta maintained its closed, hierarchical society rather than adopting Athens’ more inclusive citizenship model.

- Example: The continued subjugation of the helot (slave) population and the rigid class structure prevented Sparta from tapping into the broader human resources that had fueled Athenian dynamism.

Thucydides as Therapist

- If Athens and Sparta are the battling parts of the psyche, Thucydides is like the observing consciousness that can reflect on their interplay. His historical analysis models how we can examine the conflicts in our own nature.

- Like a good therapist, Thucydides shows the dysfunctions that arise when one side of the psyche dominates the other, whether that is the Athenian unconscious run amok or the Spartan ego imposing a false order.

Conclusion: Learning from the Ancient Greeks

In the end, the Peloponnesian War wrecked the classical Greek world and left both Athens and Sparta shadows of their former glory. However, its real import is not what it destroyed but what it revealed about the recurring patterns and challenges of the human condition.

“I will be satisfied if my history is judged useful by those who want to understand clearly what has happened – and what like it will happen again in the future.” – Thucydides

By pondering this pivotal event through the insights of depth psychology, we see how the struggles of these ancient civilizations mirror timeless struggles within the human heart and mind. The enduring legacy of this war and the thinkers who lived it, from Thucydides to Socrates, is to spur us to seek that integration and balance that they found so elusive – a dynamic harmony of complementary opposites, both within and without. For as the Delphic maxim reminded the Greeks, and Jung echoed millennia later: “Know thyself.” Studying history is one powerful way to do just that.

Timeline of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE)

Prelude

- 446 BCE: Thirty Years’ Peace treaty signed between Athens and Sparta

First Peloponnesian War (431-421 BCE)

- 431 BCE: Outbreak of war; Sparta invades Attica

- 430 BCE: Plague breaks out in Athens

- 429 BCE: Death of Pericles, Athenian statesman

- 427 BCE: Mytilene Revolt against Athens

- 425 BCE: Athens captures Spartan troops at Pylos

- 424 BCE: Brasidas, Spartan general, campaigns in northern Greece

- 422 BCE: Battle of Amphipolis; deaths of Brasidas and Cleon

- 421 BCE: Peace of Nicias signed, ending the first phase of the war

Interlude and Sicilian Expedition (421-413 BCE)

- 420 BCE: Athens and Argos form an alliance

- 418 BCE: Battle of Mantinea; Spartan victory

- 415 BCE: Athenian expedition to Sicily begins

- 413 BCE: Disastrous defeat of Athenian forces in Sicily

Decelean War (413-404 BCE)

- 413 BCE: Sparta fortifies Decelea in Attica

- 411 BCE: Oligarchic coup in Athens

- 410 BCE: Athenian naval victory at Cyzicus

- 407 BCE: Lysander appointed Spartan naval commander

- 405 BCE: Battle of Aegospotami; decisive Spartan naval victory

- 404 BCE: Surrender of Athens; end of the Peloponnesian War

Aftermath

- 404 BCE: Installation of the Thirty Tyrants in Athens

- 403 BCE: Democracy restored in Athens

Classical Literature

Iphigenia in Aulis

0 Comments