“The years, of which I have spoken to you, when I pursued the inner images, were the most important time of my life. Everything else is to be derived from this. It began at that time, and the later details hardly matter anymore. My entire life consisted in elaborating what had burst forth from the unconscious and flooded me like an enigmatic stream and threatened to break me. That was the stuff and material for more than only one life. Everything later was merely the outer classification, the scientific elaboration, and the integration into life. But the numinous beginning, which contained everything, was then.”

― C.G. Jung, preface for The Red Book: Liber Novus

James Hillman: I was reading about this practice that the ancient Egyptians had of opening the mouth of the dead. It was a ritual and I think we don’t do that with our hands. But opening the Red Book seems to be opening the mouth of the dead.

Sonu Shamdasani: It takes blood. That’s what it takes. The work is Jung’s ‘Book of the Dead.’ His descent into the underworld, in which there’s an attempt to find the way of relating to the dead. He comes to the realization that unless we come to terms with the dead we simply cannot live, and that our life is dependent on finding answers to their unanswered questions.

- Lament for the Dead, Psychology after Jung’s Red Book (2013) Pg. 1

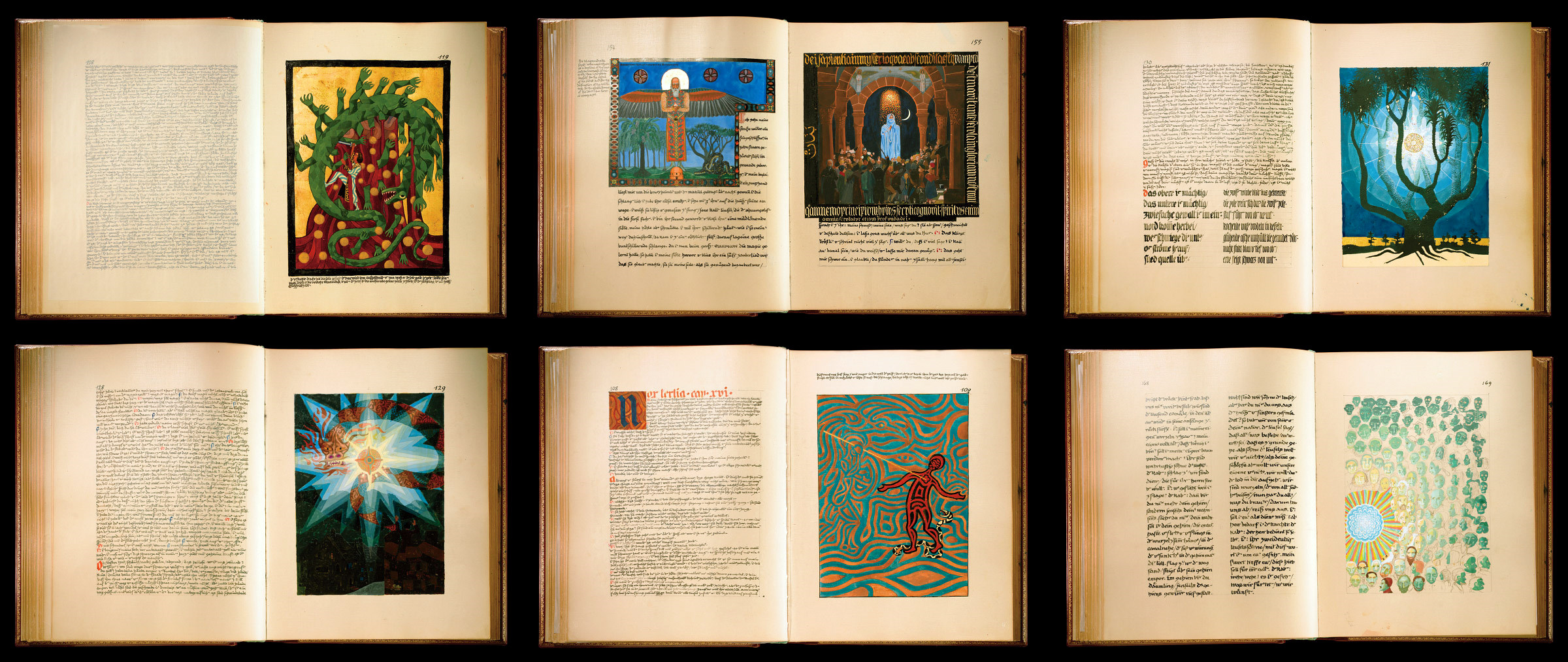

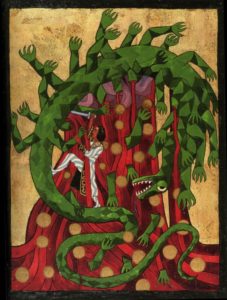

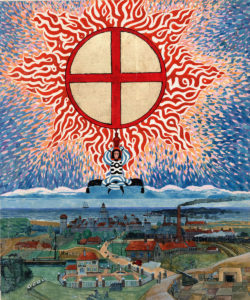

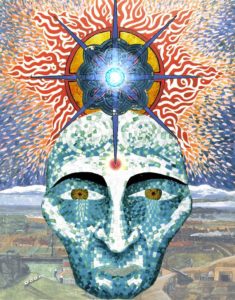

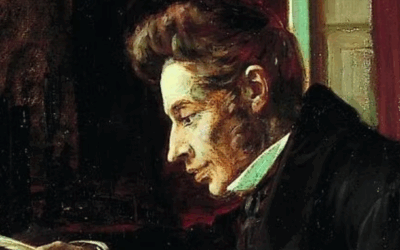

Begun in 1914, Swiss psychologist Carl Jung’s The Red Book: Liber Novus lay dormant for almost 100 years before its eventual publication. Opinions are divided on whether Jung would have published the book if he had lived longer. Regardless, the **process of writing it** was one of the most formative periods of his life. In this time, Jung came into direct, overwhelming experience with the forces of the **deep mind and collective unconscious**. For the remainder of his career, he would use this chaotic, numinous material to build his core concepts and theories about the unconscious and the repressed parts of the human psyche.

Jungian psychology, in its broadest sense, pursues two primary goals:

- To integrate and understand the deepest and most repressed parts of the human mind, leading to spiritual and psychological wholeness.

- To acknowledge and hold the tension of these repressed forces so that they don’t consume the individual, thereby protecting the ego in the process—the idea that we must not let our shadow sides eat us alive.2

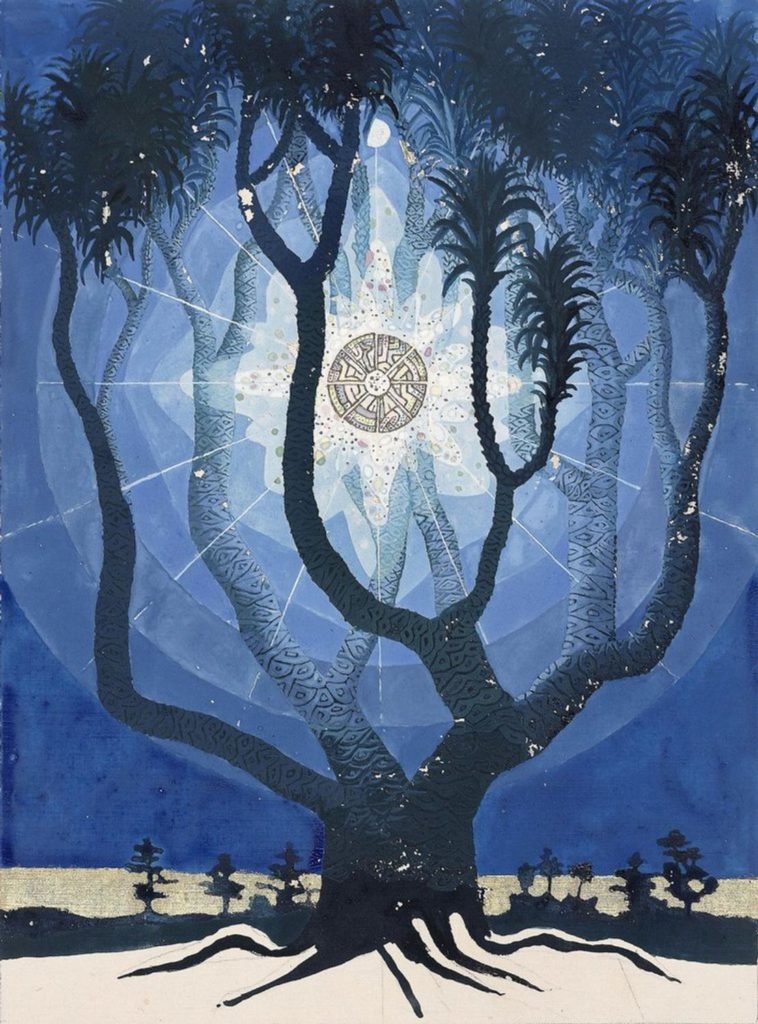

Jung called this lifelong process of self-discovery **individuation**. It is about excavating the most repressed parts of the self and learning to hold them so we can know exactly who and what we are. Jungian psychology should not be confused with religion, but rather as an attempt to build a **psychological container** for the overwhelming forces of the unconscious. It serves as both a protective buffer and a lens to clarify the self. Jung described his psychology as a bridge *to* religion, hoping it could help culture understand the vital human need for religion, mythology, and the **transcendental**.

Jung did not dislike religion; he viewed it as problematic only when its symbols became concretized and taken literally, a danger he felt was rampant in Western culture. Interestingly, Jungian psychology itself has roots in **Hindu religious traditions** (Brahman/Atman and Dharma/Moksha dichotomies). He often recommended that patients of lapsed faith return to their religions of origin, encouraging them to resume Christian or Muslim practices as a source of healing and integration. His caveat was always to return with an **open, metaphoric mind**, viewing religious traditions not as prescriptive rules or literal truths, but as **metaphors for self-discovery and processes for introspection**.

The process of writing The Red Book was itself a **religious experience** for Jung, a profound confrontation with his psyche after his falling out with Freud. Some scholars believe Jung was experiencing a temporary psychosis, while others prefer the term **”active imagination”** to describe his state. As Jungian theory often puts it: **The psychotic is drowning while the artist is swimming**; the waters both inhabit are the same.

Written in a voice similar to the King James Bible, The Red Book has a transcendent quality, produced meticulously on vellum with gorgeous hand-illuminated script, drawing inspiration from mystical and alchemical texts.1

It’s often easier to define The Red Book by what it is *not*. According to Jung, it is neither a work of art nor a scholarly psychological endeavor, nor is it an attempt to create a religion. It was an attempt for Jung to **heal himself in a time of crisis** and save himself from madness by giving a disciplined voice and a contained form to the deep forces assailing him. It became a **psychological container** to witness the deep unconscious, much in the same way religion and Jungian psychology act as containers for the ancient, oceanic forces beneath the human psyche.

🗣️ The Dialogue: Hillman, Shamdasani, and the Lament for the Dead

Lament for the Dead, Psychology after Carl Jung’s The Red Book is a published dialogue between the influential depth psychologist James Hillman and renowned Jungian scholar Sonu Shamdasani about the profound implications of The Red Book for the future of Jungian psychology. The book itself was controversial when released, partly due to the history of its authors.

Hillman, a fierce critic who had been out of the Jungian fold for decades, was a pioneer of **Archetypal Psychology**. His new psychology aimed to allow patients to **directly experience** and not merely analyze the psyche.6 Hillman’s return to the discussion during the publication of The Red Book suggests he saw in Jung’s manuscript the **disorganized blueprints** for the psychological model he had long sought to articulate but never coherently solidified.

Shamdasani, the history scholar and editor of The Red Book, brings a vital **intellectual detachment** to the conversation, contrasting Hillman’s passionate, intuitive style. As one of the foremost experts on Jung’s historical texts, Shamdasani deftly avoids the superficiality and fads that have plagued the Jungian school. The dialogue format, likely a necessity due to Hillman’s death in 2011, elevates the exchange to a philosophical dialogue where the **prophet (Hillman) and the scholar (Shamdasani)** describe their function and limitations as gatekeepers of spiritual and psychological experience.

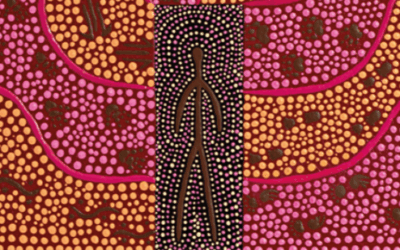

The core thesis of Lament, articulated intuitively rather than didactically, is that The Red Book is fundamentally about **“the dead.”** Hillman and Shamdasani use this term—which is intentionally left undefined and **numinous**—to describe the inescapable psychological burden of **unlived life** from our families, society, and human history. As Hillman quotes W.H. Auden:

We are lived through powers that we pretend to understand.

– W.H. Auden

This is a major tenet of Jungian psychology: adult children often struggle under the weight of the **unlived life of the parent**. The passive implication of the ethics in Lament is that to have a future, we must reckon with the unlived life of **all the dead**, facing the contradictions and half-truths of history that masquerade as tradition.

🔥 The Ethics of Descent and Return: A Tangible Application

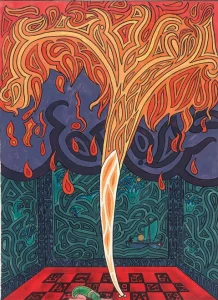

A tangible application of *Lament’s* ethics is found in Hillman’s exploration of Jung’s paradoxical contempt for the missionary **Albert Schweitzer**. Jung despised Schweitzer for having “refused the call” to bring something profound back from his descent into Africa, dismissing his humanitarian work as a failure to bring back a **”golden bough”**—a transformative cultural artifact. Jung’s similar suspicion of Westerners adopting Eastern mysticism and his dislike for modern artists who were consumed by the abstract unconscious, implies a critical ethic: **the destination is the point, not the journey.**

Jung wanted artists and spiritual explorers to make the descent into the subjective world and **return with the torch of its fire, not be consumed by its blaze**. The Red Book was Jung’s golden bough, a fully realized artifact that both celebrated and overcame the constraints of tradition. Hillman clarifies that this is the ethics that should inform modern psychology: **we must drive a tradition forward, not be slaves to repeating it.**

This ethics of **descent and return** is familiar to Americans through **Joseph Campbell’s** “monomyth” model of storytelling,3 where becoming stuck on the journey of descent turns the protagonist into an antagonist. Hillman and Shamdasani expand this—the task is to reconcile the **limits of the knowable** with the demand for tangible results.

Hillman’s struggle to articulate his Archetypal Psychology was rooted in its lack of a language or technique for direct, experiential practice. Yet, he correctly identified what was missing in clinical Jungian analysis. The Jungians who left the institutes in the late 20th century to create **somatic and experiential psychologies** were enacting Hillman’s vision: using Jungian maps with new techniques.

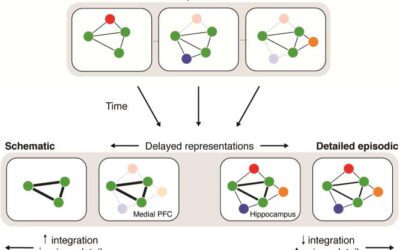

The next generation of therapy—which includes modalities like Brainspotting, ETT, **Parts-Based Therapy**,17 Somatic Experiencing, neurostimulation, and even Ketamine or Psychedelics—is the realization of Hillman’s archetypal instinct. These brain-based techniques allow for the **direct experience of the subcortical brain** to treat trauma, a necessary and more accessible path than years of talk analysis.

As the living, our ultimate job is to answer the questions and face the contradictions that our ancestors—the dead—left behind. Our life is meant to be a **eulogy for our dead**. Lament of the Dead is fascinating because it helps us see a mindful path forward that honors both **innovation and tradition**, a path essential for healing an ego-inflated world that sees no limits to growth.12

The container of the collective unconscious cannot be contained by one individual. Our mindful life is the product of the unlived life of the dead. It is our life that is their lament.

—

Further Depth Psychology Exploration

Here are a few quotes from Hillman’s *A Blue Fire* that illustrate the tension between **Soul and Spirit**—a core theme in depth psychology—and an essential component of the individuation process:

Soul…is the “patient” part of us. Soul is vulnerable and suffers; it is passive and remembers. It is water to the spirit’s fire… Whereas spirit chooses the better part and seeks to make all one. Look up, says spirit, gain distance; there is something beyond and above, and what is above is always, and always superior.

…But from the viewpoint of the psyche…movement upward looks like repression. There may well be more psychopathology actually going on while transcending than while being immersed in pathologizing. For any attempt at self-realization without full recognition of the psychopathology that resides, as Hegel said, inherently in the soul is in itself pathological, an exercise in self-deception.

Soul replies by saying, “Yes, this too has place, may find its archetypal significance, belongs in a myth.” The cooking vessel of the soul takes in everything, everything can become soul; and by taking into its imagination any and all events, psychic space grows.

— James Hillman, *A Blue Fire* (p. 123)

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Bibliography:

Abram, J. (2013). The Language of Winnicott: A Dictionary of Winnicott’s Use of Words. Karnac Books.

Addington, J. (2017). Mourning, Melancholia, and Madness: Psychoanalytic Perspectives. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 37(4), 237-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2017.1299484

Bachelard, G. (1994). The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Bernstein, J. W. (2005). The Analytical Psychology of James Hillman. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45(3), 392-423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167805277108

Bosnak, R. (2007). Embodiment: Creative Imagination in Medicine, Art and Travel. Routledge.

Brown, N. W. (1959). Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History. Wesleyan University Press.

Cambray, J., & Carter, L. (Eds.). (2004). Analytical Psychology: Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analysis. Brunner-Routledge.

Casement, A. (2001). Carl Gustav Jung. SAGE.

Dallett, J. O. (1982). James Hillman’s Archetypal Psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist, 10(3), 229-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.1982.9976858

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. Basic Books.

Guggenbühl-Craig, A. (1999). Power in the Helping Professions. Spring Publications.

Hauke, C. (2000). Jung and the Postmodern: The Interpretation of Realities. Routledge.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1996). The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. Random House.

Hillman, J. (1998). The Thought of the Heart and the Soul of the World. Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (2013). A Blue Fire: Selected Writings by James Hillman. Routledge.

Hogenson, G. B. (2001). The Baldwin Effect: A Neglected Influence on C.G. Jung’s Evolutionary Thinking. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 46(4), 591-611. https://doi.org/10.1111/1465-5922.00265

Hollis, J. (1993). The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife. Chiron Publications.

Jacobi, J. (1973). The Psychology of C.G. Jung. Yale University Press.

Jaffe, A. (1979). C.G. Jung: Word and Image. Princeton University Press.

Kugler, P. J. (1982). The Alchemy of Discourse: An Archetypal Approach to Language. Associated University Presses.

Kast, V. (1992). Joy, Inspiration, and Hope. Fromm International.

Laing, R. D. (1990). The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise. Penguin.

Libbrecht, K. (1995). Beyond the Rational Mind: The Central Role of Imagination in Human Existence. Lindisfarne Press.

Lillard, A. S. (2007). Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius. Oxford University Press.

Mathews, F. (1991). The Ecological Self. Routledge.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the Soul: A Guide for Cultivating Depth and Sacredness in Everyday Life. HarperCollins.

Moreno, A. (1995). Jung, Gods, and Modern Man. University of Notre Dame Press.

Pietikäinen, P. (1998). Archetypes as Symbolic Forms. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 43(3), 325-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/1465-5922.00019

Romanyshyn, R. D. (1982). Psychological Life: From Science to Metaphor. University of Texas Press.

Samuels, A. (1993). The Political Psyche. Routledge.

Shamdasani, S. (2003). Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge University Press.

Shamdasani, S. (2012). C.G. Jung: A Biography in Books. W.W. Norton & Company.

Slattery, D. P. (2000). The Wounded Body: Remembering the Markings of Flesh. State University of New York Press.

Stevens, A. (1994). Jung: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Tacey, D. J. (2001). Jung and the New Age. Brunner-Routledge.

von Franz, M. L. (1974). Number and Time: Reflections Leading Toward a Unification of Depth Psychology and Physics. Northwestern University Press.

Whitmont, E. C. (1969). The Symbolic Quest: Basic Concepts of Analytical Psychology. Princeton University Press.

Woodman, M. (1982). Addiction to Perfection: The Still Unravished Bride. Inner City Books.

Further Reading:

- Bair, D. (2003). Jung: A Biography. Little, Brown and Company.

- Beebe, J. (2005). Foreword. In J. Hillman, Senex and Puer (pp. xi-xv). Spring Publications.

- Chodorow, J. (1997). Jung on Active Imagination. Princeton University Press.

- Corbett, L. (2011). The Religious Function of the Psyche. Routledge.

- Hadfield, J. A. (1950). Dreams and Nightmares. Pelican.

- Huskinson, L. (Ed.). (2014). Eavesdropping: The Psychotherapist in Film and Television. Routledge.

- Hillman, J. (1964). Suicide and the Soul. Spring Publications.

- Hillman, J. (1982). Anima Mundi: The Return of the Soul to the World. Spring Publications.

- Hillman, J. (1989). A Blue Fire. Harper Perennial.

- Jacobi, J. (1942). The Psychology of C.G. Jung. Yale University Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1969). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche (2nd ed.). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Kalsched, D. (1996). The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. Routledge.

- Moore, T. (1994). Soul Mates: Honoring the Mysteries of Love and Relationship. HarperOne.

- Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge.

- Tacey, D. J. (2013). Edge of the Sacred: Jung, Psyche, Earth. Springer.

0 Comments