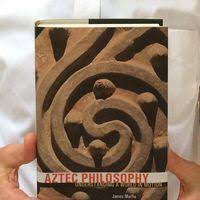

Unlocking the Mysteries of Aztec Philosophy

Unlocking the Mysteries of Aztec Philosophy

When Hernán Cortés and his expedition arrived in the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, in 1519, they were initially received with curiosity and even reverence by the Aztec emperor, Montezuma II.The Aztecs, interpreting the arrival of the Spanish as a potentially significant event, offered gifts and welcomed them with hospitality. In one encounter, Cortés asked Montezuma about his beliefs, inquiring about the Spanish understanding of God. Montezuma’s response was cryptic and revealing. He reportedly told Cortés that their gods were dead, referring to the deities of the Aztec pantheon.

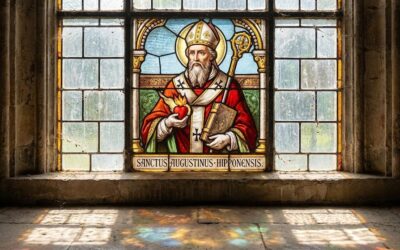

This statement puzzled the Spanish, who were devout Catholics and did not comprehend the Aztec’s complex spiritual beliefs.According to another account, when the Spanish conquered the Aztec empire the Spanish forced Aztecs to smash the carvings they thought were pagan idols telling them to “smash the gods”. The Aztecs told the Spanish that they could breaks the rock carvings, but that the gods were not there. This confused the Spanish, who thought the Aztecs were lying.When seen through the lens of Aztec spirituality and the fluid concept of “teotl,” may have been an attempt to convey that the Spanish gods were foreign and disconnected from the vibrant, ever-flowing divine energy that the Aztecs revered.

Introduction to Aztec Philosophy

I have always been fascinated with mythology and its role in understanding the human psyche. At Sewanee I got a comparative religion major and developed a profound appreciation for the intricacies of ancient religions and myths. However, Mesoamerican mythology, particularly that of the Aztecs, has remained relatively elusive in Western scholarship. This gap can be attributed to the Spanish conquest of Mexico, which led to the destruction of numerous Mesoamerican historical records and oral traditions. It is also different from other mythological pantheons to the point that scholars have had a hard time understanding any of the basic assumptions. For example most people assume that because the Aztecs had multiple deities they were polytheistic. Maffie argues in this book that they were actually monistic and that the deities were understood as either dead and already expressed forces or cosmic patterns of energy expression all lumped into their understanding of the primal chaotic form “teotl”. Teotl could mean chaos here. It could also mean energy. It could also mean metaphysical and psychical patterns. In western scholarship it has been oversimplified to be understood as gods or a specific god its patterns take the shapes of.

A Fresh Perspective

A Fresh Perspective

Maffie’s “Aztec Philosophy” takes a groundbreaking approach to understanding Aztec religion, culture, and philosophy. He challenges the Western perspective that has often been applied to analyze Aztec beliefs. Instead, Maffie delves deep into primary sources, observing Aztec thought from their own viewpoint. His unique perspective leads him to conclude that Aztec religion isn’t purely polytheistic, as is the case with ancient Greek or Norse religions, but rather leans toward pantheism. In this view, various deities are seen as different expressions of a single divine life force manifesting in all patterns of energy.

Teotl: The Underlying Energy and Its Forms

At the heart of Aztec philosophy lies the concept of “teotl,” an underlying force of energy, culture, and change that permeates all existence. Everything, including the forces of nature and humanity, is believed to be composed of this primordial energy. Western translations often equate “teotl” to “god,” which, Maffi argues, is a limited interpretation. Instead, he suggests that “teotl” represents a metaphysical reality—an intricate intersection of energy manifesting in various forms, shaping the Aztec worldview.

Understanding Aztec Culture through Energy Manifestations

Understanding Aztec Culture through Energy Manifestations

Maffie’s work sheds light on how the Aztecs perceived the manifestations of “teotl.” These manifestations primarily fall into three categories:

- Olin – The Wave of Time: Aztecs viewed time not as a linear progression but as a series of events, each representing a wave of energy. These waves gave rise to different occurrences in the universe.

- Malinalli – Duality: The Aztecs observed a constant interplay of dualities, such as life and death, male and female, order and chaos. These dualities were seen as integral to maintaining balance in the world.

- Nepantla – Weaving of Forces: Aztecs believed that various cosmic forces needed to be harmoniously woven together to prevent chaos from prevailing. This weaving represented the unity amidst the inherent chaos in the universe.

Rethinking Human Sacrifice

One of the most sensationalized aspects of Aztec culture is their practice of human sacrifice. Reading about this topic led me to explore various theories, including the idea that it was due to a lack of meat in their diet due to limited livestock species or that the victims willingly participated. However, I find these explanations lacking in credibility. Through Maffie’s perspective, the concept of “teotl” provides a different framework for understanding human sacrifice. It suggests that the Aztecs believed in the cyclical nature of life and death, where sacrifices played a symbolic role in reenacting the divine sacrifices that sustained the world.

One of the most sensationalized aspects of Aztec culture is their practice of human sacrifice. Reading about this topic led me to explore various theories, including the idea that it was due to a lack of meat in their diet due to limited livestock species or that the victims willingly participated. However, I find these explanations lacking in credibility. Through Maffie’s perspective, the concept of “teotl” provides a different framework for understanding human sacrifice. It suggests that the Aztecs believed in the cyclical nature of life and death, where sacrifices played a symbolic role in reenacting the divine sacrifices that sustained the world.

Exploring the historical interactions between the Aztecs and Spanish conquistadors takes on new significance when viewed in the context of Aztec philosophy. The Aztec perspective on their gods as manifestations of “teotl” rather than idols helps explain the Spanish misinterpretations and the subsequent clash of civilizations. The title “Aztec Philosophy” might mislead some readers, Maffi’s work offers a helpful perspective that transcends traditional interpretations, reshaping our understanding of Aztec culture and beliefs.

Patterns in Aztec Art: Expressions of Teotl

It is often assumed that Aztec art lacks accurate scale, proportion or traditional perspective because it had not been discovered yet. This is false as this technology is reflected in the works of art to the empire PREVIOUS to the rise of the Aztecs. As I delved deeper into James Maffi’s exploration of Aztec philosophy, one of the most captivating revelations was the profound connection between Aztec art and their understanding of “teotl.” The patterns and intricate designs that adorn Aztec art pieces are not mere aesthetic choices; they are intricate expressions of their metaphysical beliefs. Aztec art, often regarded as perplexing, becomes more understandable through Maffie’s insights. By understanding the universe as an ever-changing energy pattern, Aztec art becomes a representation of this worldview. The dismembered moon god, for instance, becomes a multi-dimensional piece of art that can be appreciated from various angles, much like Picasso’s paintings.

In Aztec philosophy, “teotl” is the underlying energy and essence that infuses all of existence. It’s the cosmic force that gives rise to both the tangible and intangible aspects of the world. This understanding of reality as an ever-flowing stream of energy shaped how the Aztecs perceived and represented the world around them, including their art. When we examine Aztec pottery, textiles, and other artistic creations, we begin to see a recurring theme: the depiction of “teotl” in its various forms. These patterns are weave like and hard to comprehend. Figures blend together with only pieces of the greater whole visible on temple walls.

1. Symbolism in Patterns

Patterns in Aztec art are rich in symbolism. They often incorporate intricate geometrical shapes, spirals, and repetitive motifs that convey the cyclical nature of existence. These patterns are not just decorative; they represent the perpetual flow and interconnectedness of “teotl” in all things. Just as “teotl” is in a constant state of flux, so too are the patterns in Aztec art, creating a visual representation of the ever-changing cosmic energy.

2. Divine Manifestations

For the Aztecs, their gods were not distant, separate entities but manifestations of inevitable recurring patterns of “teotl” itself. This belief is reflected in their art, where deities are often depicted with intricate patterns and symbols that represent their unique aspects and attributes. The patterns on the clothing, headdresses, and jewelry of these divine figures are not merely ornamental; they serve as a visual language, conveying the multifaceted nature of “teotl” and its expression through the gods.

3. The Dismembered Moon God and Picasso’s Influence

One of the most intriguing examples of this connection between Aztec art and “teotl” is the depiction of the dismembered moon god, Coyolxauhqui. From a Western perspective, this portrayal might seem gruesome or perplexing. However, Maffi’s interpretation sheds new light on this representation. By understanding the universe as an ever-changing energy pattern, the dismembered moon god becomes a multi-dimensional piece of art that can be appreciated from various angles, much like Picasso’s painting, Guernica.

4. Cosmic Harmony and Balance

The Aztecs believed in the importance of maintaining cosmic harmony and balance to prevent chaos from prevailing. Patterns in their art often reflect this worldview, with dualities like life and death, order and chaos, woven into the designs. These dualities were not seen as conflicting forces but as complementary aspects of the same divine energy.

These are just a few insights from the book. If it interests you, check it out!

A 500 year old conspiracy theory

This is not mentioned in the book but it has always been an fascinating theory to me so I thought I would mention it.

Before the Aztecs, there was the Toltec civilization. When the Toltec empire fell, the Aztecs adopted many of the Toltec religious belief, government structure, philosophy and technology. The Aztec leaders even claimed lineage from the Toltec emperors to legitimize their rule. They then moved their civilization to the Valley of Mexico. Now, here’s where it gets interesting. Legend has it that when the disgraced Toltec emperor saw his city falling, he gathered his closest soldiers and set sail on a boat in disgrace in the direction of Mexico. His plan was to head north, where he intended to establish a new civilization due to his disgrace in Mesoamerica. His exile is often cited as due to “drunkenness” or an embarrassing incident. He sailed in the direction of what we now know as California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Colorado. Notably, this region was inhabited by what we now call the Anasazi people.

In North America, especially in the upper parts, there aren’t many domesticate-able plants or animals, resulting in fewer permanent civilizations. You won’t find much in the way of permanent architecture, systemic large scale slavery, or human sacrifice. These were all Mesoamerican Aztec constructs. However, the Anasazi civilization in the Four Corners area (Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona) stands out as a unique exception. All of those things were found there out of the blue, with little archaeological explanation.

The Anasazi constructed elaborate cliff dwellings, practiced human sacrifices (a rarity in that region), and even engaged in cannibalism, unlike other cultures in the vicinity. They were also known to have had a slave system. It was also organized like an empire. At some point, the Anasazi civilization lost control, either through invasion or internal destabilization, leading to its disintegration. Some people decided to leave, possibly due to the oppressive regime, and their descendants might have become something akin to the modern Pueblo tribes.

Interestingly, the Navajo word “Anasazi” translates to “ancient enemy,” suggesting that the current tribes in the area don’t remember them fondly.

Now, here’s the conspiracy theory, which is likely just a coincidence but intriguing nonetheless: Some believe that the disgraced Toltec emperor sailed into the Four Corners area, hiked further inland, and founded the Anasazi civilization. This theory attempts to explain the sudden appearance of architectural sophistication, cannibalism, human sacrifice, and slavery in an area where they were historically absent. Could this Aztec myth about the disgraced emperor have been true?

I find this theory fascinating, but it’s crucial to remember that it’s not supported by concrete evidence. It’s just food for thought, not something covered in the book.

Watch the video review of the book below and check out our podcast and youtube!

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

Anthropology

Bibliography:

Maffie, James. “Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion.” University Press of Colorado, 2014.

Further Reading:

- León-Portilla, Miguel. “Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Nahuatl Mind.” University of Oklahoma Press, 1990.

- Carrasco, David. “The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction.” Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Clendinnen, Inga. “Aztecs: An Interpretation.” Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Read, Kay Almere. “Time and Sacrifice in the Aztec Cosmos.” Indiana University Press, 1998.

- Townsend, Richard F. “The Aztecs.” Thames & Hudson, 2009.

- Smith, Michael E. “The Aztecs.” Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Caso, Alfonso. “The Aztecs: People of the Sun.” University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

- Brumfiel, Elizabeth M., and Gary M. Feinman, eds. “The Aztec World.” Abrams, 2008.

- Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel. “Handbook to Life in the Aztec World.” Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Pasztory, Esther. “Aztec Art.” University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

0 Comments