Insights from Greek, Norse, Egyptian, and Hindu Mythology for Psychotherapy, Creativity and Trauma

Why do Depth Psychologists Use Mythology in Therapy?

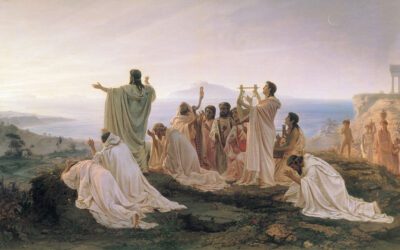

Mythology has long been recognized as a powerful tool for understanding the human psyche and the complexities of consciousness. Through vivid narratives and symbolic imagery, myths from around the world offer profound insights into the intricate workings of the mind, the nature of the self, and the universal experiences that shape our lives.

Many therapists and patients alike have wondered about the relevance of mythology in the context of psychotherapy, particularly when dealing with trauma and the development of intuition. While myths may seem like ancient stories far removed from modern psychological concerns, they are in fact deeply connected to the fundamental processes of healing, growth, and self-discovery.

At their core, myths are projections of the human psyche, reflecting the various aspects of the self and the archetypal patterns that shape our experiences. The characters and themes in these stories represent different facets of consciousness, from the conscious ego to the unconscious shadow, and the dynamic interplay between them mirrors the ongoing process of psychological integration and individuation.

For therapists, understanding the symbolic language of mythology can provide a valuable framework for helping patients navigate the complex terrain of their inner worlds. By recognizing the archetypal themes and motifs that emerge in a patient’s personal narrative, therapists can help them make sense of their experiences and find meaning in their struggles.

One of the most powerful mythological templates for understanding the process of psychological growth and transformation is the hero’s journey. This universal pattern, found in myths and stories across cultures, describes the archetypal journey of the individual from the known world of the ego into the unknown realm of the unconscious, where they must confront their deepest fears, desires, and traumas in order to achieve a higher level of self-awareness and integration.

Greek Mythology:

Greek mythology is a treasure trove of psychological insights that continue to resonate with modern psychotherapy. The stories of figures like Cassandra and Chiron, and literary works like Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy, offer profound reflections on the nature of intuition, trauma, and the self. These ancient narratives find echoes in contemporary research, mirror sociopolitical shifts, and reveal timeless archetypes of the human psyche. By examining these myths alongside other mythological traditions like Norse, Hindu, and Egyptian lore, we can gain a richer understanding of the complex, multifaceted self and the transformative journey of therapy.

Cassandra and Chiron: The Wounds and Gifts of Intuition

Intuitive feeler personality types, often associated with the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) categories of INFP, INFJ, ENFP, and ENFJ, have been observed to have the highest likelihood of accurately predicting outcomes in various domains, including politics, personal relationships, and business. However, despite their heightened intuitive abilities, they often face the paradoxical challenge of being the least likely to be believed by others. This can lead to feelings of insecurity and the experience of being “gaslit,” as their valid concerns and insights are dismissed or undermined.

In the business world, individuals with strong intuitive capabilities can be invaluable assets, offering unique perspectives and anticipating potential challenges or opportunities that others may overlook. However, their tendency to disrupt established bureaucratic structures and challenge conventional thinking can sometimes result in them being perceived as troublesome or even threatening to the status quo. As a result, they may face punishment or marginalization within organizational hierarchies.

This dynamic bears a striking resemblance to the archetypal stories of Cassandra and Chiron in Greek mythology. Cassandra, gifted with prophetic vision by Apollo but cursed to never be believed, embodies the plight of those whose intuitive warnings go unheeded. Her story resonates deeply with the experiences of many trauma survivors, who often develop heightened intuitive capacities as a result of their ordeals. The hypervigilance and acute threat perception that frequently follow traumatic events can manifest as an uncanny ability to read subtle nonverbal cues and sense impending danger. However, like Cassandra, these individuals may find their insights dismissed as mere “madness” by those around them.

Similarly, the figure of Chiron, the wounded healer, represents the transformative potential of channeling one’s own pain and suffering into the service of others. Chiron’s myth suggests that our deepest wounds can become the source of our greatest gifts, and that the path to healing others often involves confronting and integrating our own traumas. This archetype is particularly relevant for survivor-therapists, who draw upon their own experiences of trauma to empathize with and guide their clients towards recovery.

Contemporary research in the fields of psychology and neuroscience lends credence to these intuitions about intuition. Studies have demonstrated that trauma survivors often develop a heightened capacity for reading nonverbal cues and detecting potential threats, skills that are honed through the necessity of avoiding further harm. While this heightened attunement can be a valuable asset in certain contexts, it can also be experienced as a burden, leading to constant feelings of anxiety and hyperarousal.

The work of renowned trauma experts like Judith Herman and Bessel van der Kolk has shed light on the complex dynamics of trauma and its impact on intuitive perception. Their research highlights the importance of validating and honoring the intuitive knowledge of trauma survivors, rather than dismissing or pathologizing their experiences. By creating safe spaces for survivors to process their traumas and develop a more integrated sense of self, therapists can help them harness their intuitive gifts in a way that promotes healing and resilience.

Ultimately, the stories of Cassandra and Chiron, as well as the experiences of intuitive feeler personality types and trauma survivors, underscore the complex and often paradoxical nature of intuition. While intuitive insights can be a source of great wisdom and guidance, they can also be met with skepticism, dismissal, and even hostility from those who are threatened by their disruptive potential. By honoring and validating the intuitive knowledge within ourselves and others, we can begin to harness its transformative power and use it in service of personal and collective healing.

The Oresteia: Reason, Intuition, and the Evolution of Justice

Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy, comprising Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides, is a profound meditation on the nature of justice, guilt, and moral responsibility. The cycle traces the tragic downfall of the House of Atreus, from Agamemnon’s fateful decision to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia to his own murder at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. Their crime is avenged by Agamemnon’s children Orestes and Electra, setting in motion a harrowing legal battle that ends in Orestes’ trial before the Areopagus court.

On a political level, the trial scene in The Eumenides reflects the historical shift from archaic blood-vengeance codes to democratic legal institutions that was occurring in Athens during Aeschylus’ lifetime. The play can be read as a metaphor for the uneasy transition from an old intuitive order, represented by the Furies who relentlessly hound Orestes for his matricide, to a new rational order, championed by Apollo and Athena who argue for mercy and understanding.

Yet this is no simple allegory of progress, for Aeschylus recognizes the enduring importance of intuition, emotion, and the irrational in human affairs. The Furies, though terrifying and implacable, serve a vital role in upholding the moral fabric of society and honoring the primal bonds of blood. They cannot simply be banished or repressed, but must be integrated and given a place of honor, as Athena does by establishing their cult at the end of the trilogy.

Depth psychologists like Erich Neumann and James Hillman have interpreted the Oresteia as a powerful depiction of the individuation process, the lifelong struggle to reconcile the conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche. Orestes’ crime represents a necessary breaking away from the maternal matrix, the comfort zone of convention and instinct, and his eventual acquittal reflects the emergence of a new, individualized self. Yet this self rests on a fragile synthesis of opposing forces – masculine and feminine, reason and emotion, civilization and nature – that must be continually renegotiated.

Each character in the drama embodies a different aspect of the psyche’s developmental journey. Agamemnon, rigidly bound to the old warrior code, fails to question the prevailing ethos and brings destruction on himself and his family. Clytemnestra, consumed by rageful vengeance, acts out the darkest impulses of the neglected feminine. Electra, trapped in bitter resentment, channels her rage into the cause of righteous revenge.

It is Orestes who must bear the burden of synthesizing these warring energies and forging a new identity. His hesitation and uncertainty reflect the ego’s difficult task of navigating between the demands of instinct and morality, autonomy and relatedness. In the end, he must surrender his fate to the wisdom of the larger Self, personified by Athena, trusting that the very conflicts that torment him contain the seeds of a new order.

Repetition and the Hero’s Journey

The theme of repetition, of unwittingly re-enacting the very fate one tries to avoid, is a central motif of Greek myth. From Oedipus’ doomed efforts to elude the prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother, to the recurrent atrocities that befall the House of Atreus, these stories speak to the tragic dimension of human existence, the feeling that we are caught in patterns larger than ourselves.

Yet these myths also encode the way out of tragic repetition – the path of the hero’s journey. In tales like the Odyssey, the hero must undertake a perilous voyage into the unknown, confronting monsters and temptations that represent the unintegrated aspects of his psyche. Only by descending into the underworld and wrestling with his inner demons can the hero hope to break free of the cycles of trauma and fate that have entrapped him.

This archetypal pattern, identified by mythologist Joseph Campbell, has profound implications for therapy. Clients seeking help are often trapped in self-defeating patterns, unconsciously repeating the traumas of their past. The therapist’s task is to help them bring these patterns into awareness, to confront the pain they have been avoiding, and to write a new story for their lives.

In mythic terms, the therapist is akin to the helpful figures the hero meets on his journey – the wise old man, the goddess of wisdom, the animal guide – who provide crucial aid and insight. By holding up a mirror to the client’s inner world, the therapist helps them navigate the labyrinth of the psyche and emerge with a fuller, more integrated sense of self.

Norse Mythology:

The Trickster’s Shadow

While the Norse pantheon includes familiar figures like Odin, Thor, and Freyja who preside over wisdom, strength, and love, it is the trickster god Loki who embodies the psychological principle of enantiodromia – the tendency of things to turn into their opposite. Mercurial and maddening, Loki defies categorization, shifting from friend to foe, from clever prankster to malevolent destroyer.

Loki’s role in Norse myth is to destabilize the status quo, to introduce discord and disarray into the well-ordered world of Asgard. He is the gadfly that stings the gods out of their complacency, the jester who exposes their hypocrisy and hubris. In tales like the Lokasenna, he crashes the gods’ feast and airs their dirty laundry, taunting them with reminders of their infidelities, cowardice, and broken oaths.

Yet Loki is no mere villain; he is a necessary part of the cosmic balance. His mischief keeps the gods from stagnating into sterile perfection. It is Loki who brings about the birth of Odin’s wondrous steed Sleipnir, and who orchestrates the creation of treasures like Thor’s hammer Mjölnir. Even his most destructive acts, like engineering the death of Baldr, serve to set in motion the cycles of transformation that keep the cosmos dynamically alive.

In psychological terms, Loki represents the shadow – the repressed, disowned parts of the self that we try to hide from ourselves and others. Like the shadow, Loki embodies qualities that are deemed unacceptable or threatening to the ego’s sense of identity. His shape-shifting nature reflects the protean, elusive character of the unconscious, which defies the ego’s attempts to pin it down or control it.

Loki’s ultimate fate, to be bound in the entrails of his own son until the end of time, mirrors the psychic pain that results from trying to chain up the shadow. The more we try to deny our darker impulses, the more they turn against us, twisting into monstrous shapes. Yet myth also suggests that the shadow contains untapped creativity and vitality, qualities needed for true wholeness. Learning to dialogue with the inner trickster, to accept and integrate our inconsistencies and flaws, is an essential part of individuation.

Hindu Mythology: The Kaleidoscopic Self

The colorful pantheon of Hindu deities, with their myriad forms, consorts, and avatars, reflects a radically different conception of the self than the one found in Western monotheism. Here the emphasis is not on sustaining a single, unchanging identity, but on recognizing the fluid, multifaceted nature of the self. Gods like Vishnu and Shiva shape-shift from one incarnation to the next, expressing different qualities in different contexts.

The Jungian analyst John Beebe mentions this “kaleidoscopic” view of the self finds support in contemporary cognitive science. Psychologists like Ulric Neisser and Paul Rozin have proposed that the self is not a single entity, but a loose confederation of sub-selves, each with its own agenda and perspective. At any given moment, a different sub-self may take the controls, depending on the situation and the brain’s shifting dynamics. This modular view helps explain the inconsistencies and contradictions that characterize human behavior.

The Hindu model takes this idea even further, seeing the self as a microcosm of the divine macrocosm. The Upanishads declare “Tat Tvam Asi” – “Thou art That” – meaning that the individual self (Atman) is ultimately identical with the universal Self (Brahman). Our sense of being a separate, isolated ego is just a temporary delusion; in reality, all things are emanations of one infinite consciousness.

This non-dual vision was deeply influential for pioneering psychologists like William James and Carl Jung. James saw the self as a permeable “bundle” of sensations and impressions, constantly blending with the larger “stream of consciousness.” Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious proposed that beneath the individual psyche lay universal archetypes and instincts shared by all humanity.

The ideal of the self presented in Hindu myth is not a static perfection, but a dynamic dance of opposites. Gods are paired with goddesses, demonic “asuras” battle heavenly “devas,” and the path to liberation winds through sensual indulgence as well as ascetic renunciation. The goal is not to eradicate desire or achieve a bland equanimity, but to embrace all facets of experience in a spirit of ecstatic play.

For therapists working cross-culturally, engaging with Hindu myth can help loosen the Western conception of the unitary, autobiographical self. Clients from Asian and other non-Western backgrounds may have very different notions of personal identity that need to be honored and worked with. More broadly, Hindu thought challenges all of us to expand our sense of self, to look beyond our narrow ego-identifications and connect with a larger, more luminous awareness.

The Bhagavad Gita: The Yoga of Action and the Nature of the Self

Egyptian Mythology:

Dismemberment and Re-membering

The ancient Egyptians viewed human life as an eternal cycle of death and rebirth, reflected in the daily arc of the sun god Ra and the annual flooding of the Nile. This cyclical sensibility permeates Egyptian myth, most notably in the story of Osiris, who is murdered and dismembered by his brother Set, only to be reassembled and resurrected by his wife Isis and son Horus.

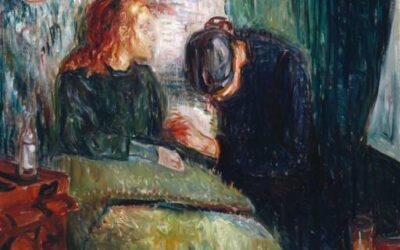

The Osiris myth provides a powerful template for the process of psychic healing. It suggests that the self is not a fixed, invulnerable essence, but a fragile construction that can be shattered by trauma and loss. The experience of being “dis-membered,” of having one’s identity broken down into disparate pieces, is a common one in therapy. Clients may feel that crucial parts of themselves have been lost, cut off, or killed due to overwhelming stress or abuse.

The mythic response to this crisis is not to try to put the shattered self back together unchanged, but to “re-member” it in a new, more resilient form. Isis does not simply restore Osiris to his former state, but transforms him into the lord of the underworld, patron of regeneration. The reassembled self is not a perfect replica of the old self, but a wiser, more compassionate version that has integrated the lessons of its brokenness.

This theme of creative reconstruction runs through many Egyptian myths. When the aging sun god Ra grows weak, he merges with Osiris each night to be reborn each dawn. When the warrior goddess Sekhmet runs amok, sowing chaos, she is pacified with ceremonial beer and converted into the gentler Hathor. The Egyptian worldview is one of perpetual metamorphosis, where destruction and creation are two sides of the same cosmic process.

Egyptian myth also emphasizes the importance of balance and reciprocity in maintaining the self. The concept of Ma’at, the principle of harmony and right relationship, is central to Egyptian ethics and spirituality. Individuals were expected to cultivate Ma’at in their own lives by dealing honestly, fulfilling their social roles, and keeping their desires in check. After death, one’s heart would be weighed against the feather of Ma’at to determine one’s moral worth.

In psychological terms, Ma’at can be understood as the capacity to regulate the conflicting drives and impulses within the psyche. When the self is out of balance, when one part of the personality dominates at the expense of others, neurosis and suffering result. The goal of therapy, like the goal of Egyptian spiritual practice, is to restore inner harmony, to help the client develop a flexible and adaptive ego that can navigate life’s challenges with integrity.

The ultimate aim of this process is not just personal well-being, but the realization of one’s interconnectedness with all of life. The Egyptian vision of the afterlife was not a solitary paradise, but a social sphere where one would reunite with loved ones and contribute to the cosmic order. In much the same way, depth psychology sees the goal of individuation not as isolated self-actualization, but as the forging of a more conscious relationship with the collective unconscious, the archetypal matrix that connects us to our fellow humans and the wider web of nature.

The Creation Myth of Heliopolis: The Emergence of Order from Chaos

The creation myth of Heliopolis, one of the oldest and most influential of Egyptian cosmogonies, tells the story of how the ordered universe emerged from the primordial chaos. In the beginning, there was only the dark, watery abyss of Nun. From this abyss emerged the self-created god Atum, who took the form of a mound of earth rising from the waters. Atum then created the first divine couple, Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), by spitting or sneezing them out. Shu and Tefnut in turn gave birth to Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), who were separated by their father Shu. Geb and Nut then produced Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys, the main protagonists of the Osirian drama.

This myth reflects the Egyptian conception of the cosmos as a delicate balance of opposites – light and dark, order and chaos, male and female. The act of creation is portrayed not as an ex nihilo event, but as a gradual process of differentiation and separation, with each generation of gods representing a further stage in the unfolding of the universe. The image of the primeval mound, the benben, became a key symbol in Egyptian art and architecture, reflected in the shape of the pyramids and the obelisks that marked the sun temples.

The Heliopolitan myth also emphasizes the role of the sun god Ra, who was often merged with Atum as the creator deity. Ra’s daily journey across the sky in his solar bark, and his nightly voyage through the underworld, battling the forces of darkness, became a potent metaphor for the cyclical nature of time and the eternal struggle of life against death. In the New Kingdom, this solar theology reached its apex with the rise of the cult of Amun-Ra, the hidden creator god whose power sustains the universe.

From a psychological perspective, the Heliopolitan myth can be seen as a map of the emergence of consciousness from the unconscious. Atum, the self-generated god, represents the spark of awareness that arises spontaneously from the depths of the psyche. The successive generations of gods reflect the gradual differentiation of this awareness into distinct cognitive and emotional functions, culminating in the ego’s capacity for self-reflection and moral judgment. The solar journey of Ra can be seen as a symbol of the individuation process, the ongoing quest for wholeness and enlightenment in the face of life’s challenges.

Bibliography:

- Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Eliade, M. (1998). Myth and Reality. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1978). Myth and Meaning: Cracking the Code of Culture. New York: Schocken Books.

- Segal, R. A. (2004). Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Armstrong, K. (2005). A Short History of Myth. Edinburgh: Canongate Books.

- Hillman, J. (1991). A Blue Fire: Selected Writings. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Von Franz, M.-L. (1996). The Interpretation of Fairy Tales. Boston: Shambhala.

- Bettelheim, B. (1976). The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. New York: Knopf.

- Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Henderson, J. L. (1964). Ancient Myths and Modern Man. In C. G. Jung (Ed.), Man and His Symbols (pp. 104-157). New York: Dell Publishing.

- Edinger, E. F. (1992). Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Boston: Shambhala.

- Hollis, J. (2003). Mythologems: Incarnations of the Invisible World. Toronto: Inner City Books.

- Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Chicago: Open Court.

- Kalsched, D. (2013). Trauma and the Soul: A Psycho-Spiritual Approach to Human Development and its Interruption. London: Routledge.

- Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York: Basic Books.

- Levine, P. A. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

- Woodman, M., & Dickinson, E. (1996). Dancing in the Flames: The Dark Goddess in the Transformation of Consciousness. Boston: Shambhala.

- Estés, C. P. (1992). Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. New York: Ballantine Books.

Continued Reading List:

- The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers

- Goddesses in Everywoman: A New Psychology of Women by Jean Shinoda Bolen

- King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine by Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette

- The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image by Anne Baring and Jules Cashford

- The Mythic Imagination: The Quest for Meaning Through Personal Mythology by Stephen Larsen

- The Cry of Merlin: Jung, the Prototypical Ecopsychologist by Dennis L. Merritt

- Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World by Carol S. Pearson

- Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes by Edith Hamilton

- The Feminine in Fairy Tales by Marie-Louise von Franz

- Amor and Psyche: The Psychic Development of the Feminine by Apuleius and Erich Neumann

- Mythology of the Soul: A Research into the Unconscious from Schizophrenic Dreams and Drawings by H. G. Baynes

- Oedipus and the Devil: Witchcraft, Religion and Sexuality in Early Modern Europe by Lyndal Roper

- The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft by Ronald Hutton

- Myths to Live By by Joseph Campbell

- The Wounded Healer: Countertransference from a Jungian Perspective by David Sedgwick

- Trauma and the Avoidant Client: Attachment-Based Strategies for Healing by Robert T. Muller

- Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past by Peter A. Levine

- Collective Trauma, Collective Healing: Promoting Community Resilience in the Aftermath of Disaster by Jack Saul

- The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit by Donald Kalsched

- The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment by Babette Rothschild

0 Comments