The worn pages crackle under trembling fingers. Found tucked between dusty volumes in a government surplus sale box, the document bears no official seal, no classification stamps: just densely typed pages speaking of economic shock testing, biological warfare through data collection, and the mathematics of human control. “Technical Manual TM-SW7905.1,” it claims, dated May 1979, allegedly a training document for social engineers. The finder’s heart races: Is this real? A forgotten piece of the puzzle explaining why the world feels increasingly suffocating despite unprecedented prosperity?

The worn pages crackle under trembling fingers. Found tucked between dusty volumes in a government surplus sale box, the document bears no official seal, no classification stamps: just densely typed pages speaking of economic shock testing, biological warfare through data collection, and the mathematics of human control. “Technical Manual TM-SW7905.1,” it claims, dated May 1979, allegedly a training document for social engineers. The finder’s heart races: Is this real? A forgotten piece of the puzzle explaining why the world feels increasingly suffocating despite unprecedented prosperity?

The document, known as “Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars,” purportedly originated in 1954; the same year Brown v. Board of Education shook America’s foundations, the year the CIA overthrew Guatemala’s government, the year television sets multiplied across suburban landscapes like invasive species. According to its pages, this was no coincidence. The manual describes a new form of warfare declared against civilian populations, not with bullets and bombs, but with economic models, social engineering, and information control.

The Conspiratorial Narrative and Its Uncanny Prescience

Let me be clear: I find this document fascinating not because I believe it represents an actual government manual; such crude literalism misunderstands how power operates. As filmmaker Adam Curtis brilliantly demonstrates in his work, particularly in “HyperNormalisation” and “Can’t Get You Out of My Head,” our world isn’t controlled by shadowy cabals meeting with cigars and bourbon in backrooms. Throughout history, exploitation rarely works that way. Instead, it emerges from what Curtis calls “a system that no one really controls”: a complex web of self-interested actors, technological systems, and ideological frameworks that create oppression without oppressors, violence without villains.

The profit motive doesn’t require secret conspiracies; it operates through what Gramsci called “cultural hegemony,” through tacit consent, through the invisible hand that Adam Smith warned could strangle as easily as it could guide. Curtis shows us how power maintains itself not through grand plans but through the management of perception, the narrowing of imagination, and the creation of what he terms “a fake world that everyone knows is fake.”

Yet here’s what disturbs me as a psychotherapist working in 2025: this “wild conspiracy theory” has proven eerily prescient. The paranoid, emotional analysis it offers—while literally false in its specifics—points to material and systemic failures that are devastatingly real. Like a dream that speaks in symbols, conspiracy theories often reveal truths through their very distortions. The document describes future governments that wouldn’t need traditional tools of oppression—no gulags, no secret police, no mass executions. Instead, it envisions systems that could disempower, disenfranchise, and ultimately destroy people through other means.

Reading this in our current moment, where algorithms determine what we see, where debt enslaves generations, where loneliness has become epidemic, where deaths of despair climb yearly, feels like reading tomorrow’s newspaper written forty years ago.

The Architecture of Systemic Violence

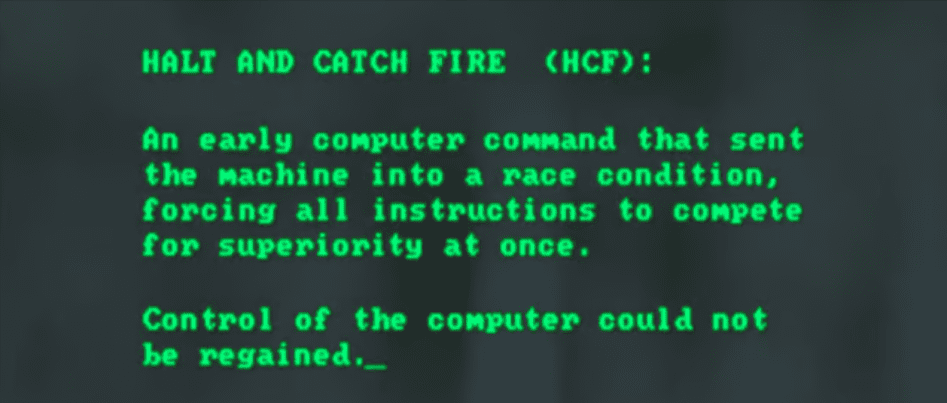

The manual describes what it calls “silent weapons”: tools of control that operate below the threshold of conscious awareness. Unlike traditional warfare, these weapons leave no visible wounds, create no martyrs, generate no obvious resistance. They work through what psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas calls the “unthought known,” shaping experience at levels too fundamental to question.

This paranoid lens, as Curtis might argue, offers something valuable: it makes visible the invisible threads of power. When people sense they’re being exploited but can’t identify the exploiter, when they feel trapped but see no prison, the conspiratorial mindset creates a narrative that, while factually wrong, is emotionally true. It’s a desperate attempt to re-enchant a disenchanted world, to give agency to systems that feel agentless.

Consider how this manifests in my practice. I see clients who feel inexplicably exhausted despite working harder than their parents ever did. They describe a sense of running on treadmills that accelerate just fast enough to keep them from falling off but never fast enough to get anywhere. They carry debt like ankle weights: student loans, medical bills, credit cards, each payment a small surrender of autonomy. They know something is wrong but can’t name it, so they reach for explanations: the Deep State, the WEF, the Illuminati. These are metaphors dressed as literals, dreams mistaken for documentaries.

The manual predicted this with chilling accuracy. It describes economic systems designed to create “induced insufficient buying power,” forcing populations into debt slavery. It outlines media strategies to fragment attention, making sustained political organization impossible. Most presciently, it describes the goal of making people “so busy with day-to-day survival that they have no time to think.”

The Psychological Mechanisms of Control

As a therapist, I’m particularly struck by how the document anticipates the psychological dimensions of systemic control. It describes strategies that mirror what we now recognize as fundamental mechanisms of psychological manipulation at scale.

Learned Helplessness

The systematic creation of situations where effort feels futile, where the link between action and outcome becomes so attenuated that people simply stop trying. Seligman’s dogs, shocked into submission, multiplied across entire populations. My clients describe this perfectly: sending hundreds of job applications into digital voids, watching housing prices rise faster than wages no matter how hard they work, feeling that the game is rigged but having no choice but to play.

Cognitive Overload

The deliberate multiplication of choices, information streams, and decisions until the mind retreats into heuristics and conformity. Barry Schwartz’s “Paradox of Choice” weaponized before he named it. Every moment demands decisions: which health insurance plan among dozens of incomprehensible options, which of a thousand investment vehicles for the retirement you’ll never afford, which brand of ethically sourced coffee to buy while the planet burns. The exhaustion is the point.

Social Atomization

The dissolution of traditional support networks, leaving individuals psychologically naked before institutional power. Bowling alone, dying alone, facing systems alone. The document predicted this with chilling precision, describing how isolated individuals would be easier to control than communities with strong bonds of mutual support.

Gaslighting at Scale

The constant revision of narratives, the multiplication of “truths,” the deliberate confusion of cause and effect until people doubt their own perceptions. When my clients say “I feel crazy,” they’re responding rationally to a world that denies their lived experience, that tells them the economy is booming while they can’t afford groceries, that insists they’re free while every choice feels predetermined.

The Prophet Motive: Predicting Our Present

What makes this document remarkable isn’t its claim to government authorship, which I doubt, but its function as prophecy. Whether written by a brilliant theorist, a disillusioned insider, or a particularly prescient science fiction writer, it demonstrates something crucial: our current dystopia was entirely predictable.

What makes this document remarkable isn’t its claim to government authorship, which I doubt, but its function as prophecy. Whether written by a brilliant theorist, a disillusioned insider, or a particularly prescient science fiction writer, it demonstrates something crucial: our current dystopia was entirely predictable.

Adam Curtis, in his essay films, repeatedly shows us this pattern: how the failure to imagine alternatives leads to a kind of technological determinism. The document’s author(s) understood that when you connect the profit motive’s endless hunger for growth with the emergence of computational power, the science of behavioral conditioning, the techniques of public relations, and the mathematics of network effects, you get a system that inevitably trends toward total control, not through conspiracy but through convergence. Each actor, the advertiser, the politician, the platform developer, the financier, pursues their narrow interest. Together, they create a prison without walls, guards, or even any conscious intent to imprison.

This is what Curtis calls “the system that no one controls but everyone accepts.” The paranoid analysis offered by documents like “Silent Weapons” serves as a kind of folk sociology, wrong in its details but accurate in its emotional mapping of power’s effects. When people say “they’re trying to control us,” the “they” might be fictitious, but the control is real. The conspiracy theory becomes a metaphor for market forces too complex to comprehend, yet too painful to ignore.

The Therapeutic Implications

In my practice, I see the casualties of these “silent weapons” daily. The young professional who can’t understand why she feels empty despite checking every box society told her to check. The father who works two jobs but can’t afford his child’s insulin. The teenager who cuts herself to feel something real in a world of curated unreality. The elderly woman isolated in her apartment, her children too busy surviving to visit.

Traditional therapy often treats these as individual pathologies: depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders. But what if we’re seeing rational responses to an irrational system? What if the pathology lies not in my clients but in the structures that shape their lives?

The Algorithmic Acceleration

The manual, written before personal computers existed, couldn’t fully anticipate how algorithms would supercharge these dynamics. Yet its core insight holds: power no longer needs to announce itself. It operates through recommendation engines that create echo chambers, credit scores that encode class warfare in mathematics, surge pricing that extracts maximum value from human need, attention markets that monetize distraction, and predictive analytics that close futures before they open.

Each algorithm, optimizing for engagement or profit, becomes a silent weapon. No malice needed, just math pursuing its assigned objective with inhuman persistence.

Resistance and Therapy

If the analysis holds, if we’re subject to systemic violence masquerading as market forces, what role can therapy play? I’ve come to believe we need therapeutic approaches that address the systemic nature of our suffering.

Naming the System

We must help clients distinguish between personal failings and structural violence. Sometimes you’re not depressed; you’re oppressed. This doesn’t mean avoiding personal responsibility, but it does mean contextualizing individual struggles within larger systems of power. When a client says “I’m a failure,” we explore: failure by whose standards? In whose game? For whose benefit?

Rebuilding Connection

We need to create spaces for genuine human contact, unmediated by platforms or profit. Group therapy becomes a form of resistance cell, a place where people can experience non-transactional relationships. The simple act of sitting in a circle, sharing struggles without competition, becomes revolutionary in a world that monetizes every interaction.

Developing Critical Consciousness

Paulo Freire enters the therapy room. We help people read the world as well as their symptoms. This means exploring how personal troubles connect to public issues, how individual anxiety might reflect collective precarity, how private despair might mirror social decay.

Practicing Prefiguration

The therapeutic space itself becomes a model for different ways of being together. We practice relationships based on mutual aid rather than transaction, collaboration rather than competition, presence rather than productivity. In this way, therapy offers a glimpse of another possible world.

Embracing Productive Anger

Instead of medicating rage or turning it inward, we help clients channel it toward systems rather than self. Anger, properly directed, becomes fuel for transformation rather than self-destruction. The question shifts from “What’s wrong with me?” to “What’s wrong with a world that makes me feel this way?”

The Paradox of Awareness

The manual contains a curious passage about “the simplicity of the silent weapon”: it suggests that the system’s power lies partly in its visibility. Like Poe’s purloined letter, it hides in plain sight. We see the algorithms, the debt, the isolation, but seeing doesn’t equal escaping.

This creates what Curtis identifies as the core paradox of our time: we live in a world where everyone knows the system is failing, but no one can imagine an alternative. The conspiracy theory, in its emotional truth, offers a kind of twisted comfort, at least someone is in control, even if they’re evil. The reality Curtis reveals is more terrifying: a system running on autopilot, optimizing for metrics that no longer serve human flourishing, defended by people who secretly know it’s broken but see no other option.

The paranoid lens, for all its distortions, captures something the rationalist lens misses: the feeling of being subjects in someone else’s experiment. When my clients describe their lives, they often use language that echoes conspiracy theories: “I feel like I’m being watched,” “Everything seems designed to exhaust me,” “It’s like they want us to fail.” The “they” is fictitious, but the design is real: emergent rather than intentional, systemic rather than conspiratorial, but no less destructive for its lack of a mastermind.

This creates a therapeutic paradox. Awareness alone doesn’t liberate; sometimes it deepens despair. My clients often say variations of: “I know the system is rigged, but I still have to pay rent.” The question becomes: How do we transform awareness into agency without falling into either naive individualism or paralyzed despair?

The Future of Resistance

Whether “Silent Weapons for Quiet Wars” represents leaked intelligence or brilliant speculation matters less than what it reveals: our current crisis was both predictable and predicted. The document serves as a mirror, showing us the logic of our own system stripped of its legitimating narratives.

As therapists, we stand at a crossroads. We can continue treating the casualties of systemic violence as individual pathologies, adjusting people to an insane system. Or we can recognize that healing, in our current moment, requires not just psychological work but political consciousness.

The silent weapons have been deployed. The quiet war rages on. But perhaps, in naming these dynamics, in understanding their operation, in building communities of resistance and care, we can begin to forge what the manual’s authors never anticipated: solidarity among the targets, therapy as liberation, healing as revolution.

The document ends with a chilling note: “The public cannot comprehend this weapon, and therefore cannot believe that they are being attacked and subdued by a weapon.” But we comprehend it now. We see the weapon because we feel its wounds. The question is: What will we do with this terrible knowledge?

In my practice, I’ve begun to see glimmers of an answer. It lies not in individual escape, there is no outside to escape to, but in collective refusal. In small groups gathering to share skills and resources. In communities practicing mutual aid. In young people choosing connection over consumption. In therapists reimagining our role not as adjusters but as accomplices in liberation.

The manual was right about one thing: the future would be a battlefield. It was wrong about another: we would not go quietly.

0 Comments