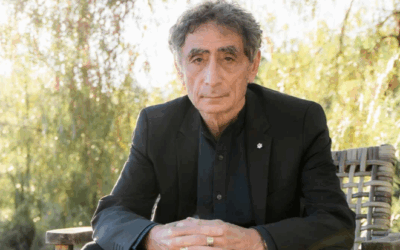

The Historian Who Rescued the Soul of Psychology

In the history of depth psychology, there is a distinct “Before 2009” and “After 2009.” Before 2009, Analytical Psychology was a field largely defined by clinical hearsay, sanitized publications, and a rigid adherence to the “scientific” face Carl Jung presented to the world in his later years. After 2009, the publication of The Red Book: Liber Novus shattered that facade, revealing the chaotic, artistic, and deeply mystical furnace from which Jung’s psychology was forged. The man responsible for this seismic shift is Sonu Shamdasani.

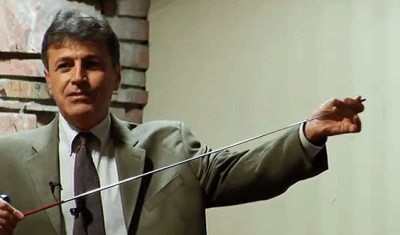

A historian of psychology, author, and professor at the School of European Languages, Culture and Society at University College London, Shamdasani is arguably the most important figure in Jungian scholarship since Jung himself. He did not merely “edit” a book; he engaged in a decades-long diplomatic and intellectual struggle to liberate Jung’s archives from the grip of family secrecy and institutional censorship. Through his work with the Philemon Foundation, Shamdasani has fundamentally restructured our understanding of the unconscious, moving it away from a clinical pathology to be fixed and toward a cultural inheritance to be explored.

Biography and Intellectual Formation

Born in Singapore in 1962, Sonu Shamdasani moved to England as a teenager. His intellectual formation was not that of a clinician, but of a rigorous historian. He earned his B.A. from Bristol University and his Ph.D. in the History of Medicine from the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine in London. This distinction is crucial: Shamdasani approached Jung not as a disciple seeking a guru, nor as a clinician seeking tools, but as a historian seeking the truth behind the myth.

In the 1980s and 90s, Jungian scholarship was often insular. Analysts wrote for other analysts, often repeating foundational myths about Jung’s break with Freud and his “discovery” of the collective unconscious without consulting primary sources. Shamdasani, utilizing his skills in historiography and his fluency in German, began to dig into the archives. What he found was a discrepancy between the “Jung Legend”—the story Jung told about himself in Memories, Dreams, Reflections—and the documentary evidence. This led to his controversial and groundbreaking work, Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science, where he systematically dismantled the “Freudocentric” history of the field.

The Saga of The Red Book (Liber Novus)

The defining achievement of Shamdasani’s career is the publication of Liber Novus, known popularly as The Red Book. For decades, this book was the “Holy Grail” of the unconscious. Bound in red leather, filled with calligraphy and terrifying paintings, it sat in a Swiss bank vault, seen only by a handful of people. The Jung family, specifically the heirs managing the estate, were protective of Jung’s reputation. They feared that releasing the Red Book—which documents Jung’s hallucinations, conversations with the dead, and visions of blood and apocalypse—would destroy his reputation as a scientist and brand him a psychotic.

Shamdasani spent years building trust with the family, specifically Ulrich Hoerni, Jung’s grandson. Shamdasani’s argument was historical: Jung’s psychology cannot be understood without the primary data upon which it is based. He argued that the Red Book was not a sign of madness, but a work of “self-experimentation” in the tradition of Goethe and Nietzsche. He convinced them that the world was ready to understand Jung not just as a doctor, but as a visionary artist. When The Red Book: Liber Novus was finally released in 2009, it was a cultural phenomenon.

Reframing Individuation

Shamdasani’s editorial commentary revealed that the Red Book was the “numinous beginning” of all Jung’s later work. Concepts that seem dry and clinical in the Collected Works (like Active Imagination) are revealed in the Red Book to be terrifying, visceral encounters with autonomous spirits. This fundamentally changed how analysts practiced: therapy was no longer about “fixing” a patient, but about guiding them through their own “Red Book” process. The goal of Individuation was reframed not as a path to sunny wholeness, but as a courageous integration of the fragmented and often terrifying aspects of the Self.

Lament of the Dead: The Dialogue with James Hillman

Following the release of the Red Book, Shamdasani engaged in a series of recorded conversations with James Hillman, the founder of Archetypal Psychology. These were published as Lament of the Dead: Psychology After Jung’s Red Book. In this book, Shamdasani and Hillman explore the most radical implication of the Red Book: the objective reality of the dead. Jung did not view the figures he met (Philemon, Salome, Elijah) merely as “parts of himself.” He treated them as the voices of the ancestral dead who had not been properly mourned or heard by the modern world.

Shamdasani argues that modern psychology is a “psychology of the living” that has forgotten the dead. We treat the past as something to be “gotten over” or “integrated.” Jung’s view, illuminated by Shamdasani, is that we are carriers of the dead. Trauma is often the result of the unquiet dead (ancestral patterns, historical wounds) pressing upon the living. The task of the individual is to answer the unanswered questions of their ancestors. This aligns with modern understandings of shadow work, where one must confront the “ghosts” of family history to find liberation.

The Philemon Foundation and The Black Books

Shamdasani realized that the standard Collected Works of C.G. Jung were insufficient. They were heavily edited, often mistranslated, and missing massive amounts of material. To remedy this, he co-founded the Philemon Foundation, an organization dedicated to preparing the unpublished works of Jung for publication. This effort culminated recently in the publication of The Black Books (2020). While the Red Book is the stylized, artistic “final draft,” the Black Books are the raw journals—the day-to-day records of Jung’s visions from 1913 to 1932. They reveal the “human” side of the revelation, showing Jung’s doubts, his struggles with his family, and the raw, unedited flow of the unconscious.

Sonu Shamdasani has arguably done more for Jungian psychology in the last 20 years than any clinician. He has saved Jung from becoming a historical footnote or a New Age caricature. Through his work, we now understand that Jung’s theories of trauma were not abstract. They were born from his own trauma—the breakdown he suffered during World War I. The Red Book is a trauma narrative. It shows us that the way through trauma is not to “fix” it, but to mythologize it—to give it form, image, and narrative until it becomes a vessel for meaning. Shamdasani points toward a future where depth psychology is not just a clinical practice for the wealthy, but a cultural hermeneutic—a way of reading history, art, and politics.

0 Comments