What is the Point of All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace

I like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky.

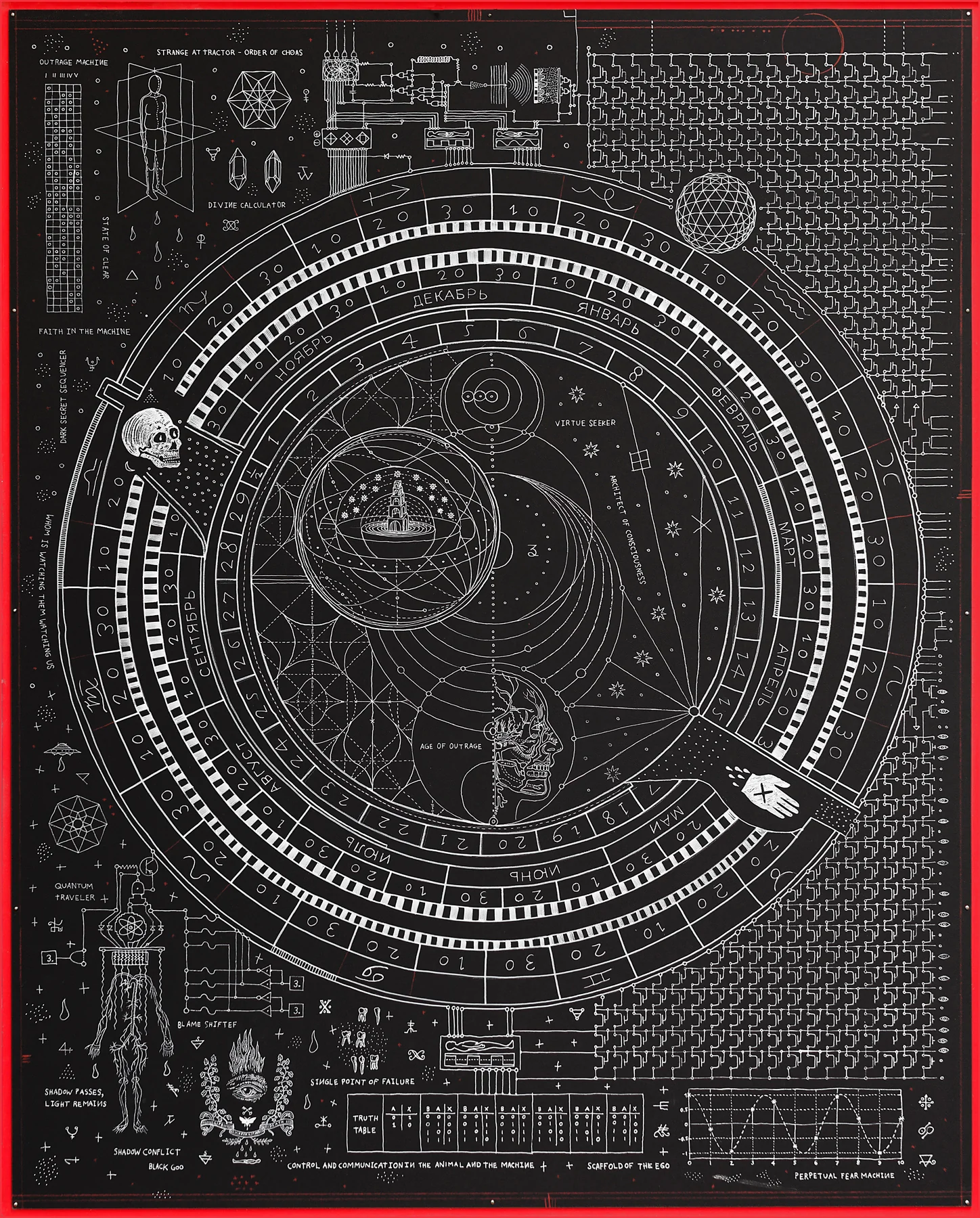

These opening lines from Richard Brautigan’s 1967 poem “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace” paint a seductive picture: a world where nature and technology blend seamlessly, where humans and machines coexist in a kind of symbiotic dance. But beneath the surface of this “cybernetic meadow” lurks a darker vision – one in which the very essence of what makes us human is reduced to mere inputs and outputs, our lives stripped of meaning and agency.

This is the central concern that animates Adam Curtis’s 2011 documentary series of the same name. Over the course of three episodes, Curtis traces the rise of the cybernetic worldview and its far-reaching consequences for our understanding of nature, society, and the self. He argues that the dream of a self-regulating, harmoniously balanced world is not only illusory, but dangerously misguided – a “fantasy of the machines” that has led us to abdicate our responsibility as thinking, feeling, autonomous beings.

At the heart of this fantasy is a fundamental misconception about the nature of complex systems, whether ecological, economic, or psychological. The cybernetic thinkers of the mid-20th century, inspired by wartime research into feedback loops and information processing, came to see the world as a vast network of interconnected nodes, each responding to and influencing the others in a constant dance of adjustment and equilibrium. In this view, the role of the individual is diminished, subsumed into the larger pattern of the system.

But as Curtis reveals, this seemingly scientific understanding of the world is shot through with ideology and hubris. The dream of a self-correcting, harmoniously balanced system is seductive precisely because it promises to relieve us of the burdens of politics and morality, of the need to make difficult choices and fight for a better world. It offers a technocratic fantasy of pure, frictionless efficiency, where the messy realities of human life are smoothed away by the elegant mathematics of the machine.

We see this fantasy play out again and again in the realms of ecology, economics, and psychology. In the 1960s and ’70s, as Curtis explores in the second part of his series, the ideas of cybernetics were taken up by a new generation of ecologists and environmental activists, who saw in the self-regulating networks of nature a model for human society. The Gaia hypothesis, first proposed by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis, imagined the Earth as a kind of super-organism, a complex adaptive system that maintained its own stability through the interplay of its constituent parts.

But as Curtis argues, this seemingly holistic vision of nature masked a darker reality. The cybernetic ecology movement, for all its talk of balance and harmony, was undergirded by a fundamentally mechanistic view of the world, one that reduced the teeming diversity of life to a set of abstract feedback loops and equations. In the process, it paved the way for a new kind of technocratic environmentalism, more concerned with managing nature than understanding our place within it.

We see a similar dynamic at work in the realm of economics, where the rise of complex financial instruments and computer-driven trading algorithms has created a kind of “black box” market, opaque and disconnected from the real-world consequences of its actions. As Curtis explores in the first part of his series, the belief that markets are inherently self-correcting and efficient has led to a abdication of political and moral responsibility, a blind faith in the wisdom of the machine.

But perhaps most insidiously, the cybernetic worldview has infiltrated our understanding of the human mind itself. The rise of cognitive and behavioral psychology in the latter half of the 20th century represented a kind of triumph of the machine metaphor, reducing the richness and complexity of mental life to a set of stimulus-response patterns and computational processes. In this view, the goal of therapy is not to explore the depths of the psyche, but to debug and optimize the software of the mind.

This is a tragically impoverished vision of what it means to be human. As any depth psychologist knows, the human mind is not a computer, neatly processing inputs and outputs according to some predetermined algorithm. We are not, at our core, rational actors seeking to maximize our utility, but deeply emotional, meaning-making creatures, shaped by forces of myth, culture, and evolutionary history that far exceed our conscious understanding.

To reduce the psyche to a set of cognitive and behavioral patterns is to miss the very essence of what makes us human – our capacity for symbolization, for narrative, for the creation and transmission of meaning across generations. It is to ignore the profound role that unconscious forces play in shaping our lives, from the archaic depths of the collective psyche to the untold stories and traumas we carry within.

This is not to dismiss the value of cognitive and behavioral therapies entirely, or to romanticize suffering as some kind of noble quest. For many people struggling with specific symptoms or maladaptive patterns, these approaches can provide real relief and practical coping strategies. But they are not sufficient, in themselves, for the deeper work of soul-making and self-discovery.

That deeper work requires that we grapple with the irreducible complexity and mystery of the human experience – the way that our lives are woven from strands of myth and history, archetype and idiosyncrasy. It demands that we confront the shadows and contradictions within ourselves, not as bugs to be fixed but as seeds of wholeness to be nurtured. And it recognizes that true transformation often involves a journey through the underworld of suffering and dissolution before rebirth can occur.

These are not processes that can be reduced to formulas or flow charts, no matter how sophisticated our models may become. They are the stuff of lived experience, of the messy, embodied, inter-subjective space between self and world. They require not just the parsing of thoughts and behaviors, but a deep engagement with the poetic, imaginal, and somatic dimensions of mental life.

At its best, psychotherapy is a crucible for this kind of transformative work – a space where two sovereign psyches can meet in a spirit of open-ended exploration, co-creating new meanings and possibilities from the raw materials of memory, emotion, and dream. This is the artistry of therapy, the alchemy of healing: not a mechanical adjustment of psychic levers and dials, but a mutual awakening to the numinous depths of soul.

In this sense, the real value of Adam Curtis’s work lies not just in his trenchant critique of the cybernetic worldview, but in his implicit challenge to reimagine the nature of the therapeutic encounter itself. If we are to truly resist the siren song of the machine, to reclaim our full humanity in an age of technocratic reduction, we must be willing to embrace the irreducible mystery and complexity of the psyche – to see therapy not as a process of optimization and control, but as a journey of discovery and self-creation.

This is a vision of therapy that is at once humbler and more ambitious than the cybernetic dream – humbler in its recognition of the limits of our understanding, more ambitious in its commitment to the unfolding of the soul. It is a vision that honors the full richness and complexity of mental life, the way that our deepest truths often lie hidden in symbol and metaphor, shadow and dream.

Ultimately, this is the great challenge that Curtis’s work poses to the therapeutic establishment: to move beyond the machine metaphors of the past century, and to embrace a more fully human vision of what it means to heal and to grow. It is a challenge to see the psyche not as a problem to be solved, but as a mystery to be lived – a challenge to recognize that, in the end, we are all watched over not by machines of loving grace, but by the untamed wildness of our own hearts.

0 Comments