Executive Summary: The Psychology of the Oresteia

The Core Conflict: Aeschylus’ trilogy is the foundational myth of Western Justice. It traces the evolution of human consciousness from “Blood Vengeance” (The Furies) to “Civil Law” (Athena/The Court).

Jungian Key Concepts:

- The Negative Mother Complex: Clytemnestra represents the devouring aspect of the mother who must be overcome for the son (Orestes) to achieve manhood.

- The Furies (Erinyes): Represent the guilt-complex and the archaic Superego that punishes instinctual transgressions with madness.

- Athena as the Self: The goddess represents the Transcendent Function—the higher consciousness that reconciles the conflict between instinct (Furies) and reason (Apollo).

Clinical Relevance: A map for treating Intergenerational Trauma. It shows that the “Curse” stops only when the individual integrates the Shadow (Furies) rather than repressing it.

What is the Oresteia? A Jungian Analysis of Justice, Guilt, and the Evolution of Consciousness

The Oresteia (458 BC) is the only surviving trilogy of Greek tragedy. It is more than a story; it is a psychological document recording the moment humanity moved from the “Law of the Jungle” to the “Rule of Law.”

From the perspective of Carl Jung and Erich Neumann, this trilogy depicts the struggle of the Ego (Orestes) to free itself from the Unconscious (The Curse/The Mother) and establish a new order of consciousness (Athena). It is a bloody, terrifying, and ultimately redemptive journey through the darkest corridors of the family soul.

I. Agamemnon: The Return of the Shadow

The Curse of the House of Atreus

The play opens in a world ruled by the “Old Law”—an eye for an eye. Agamemnon returns from Troy, expecting a hero’s welcome. He is walking into a trap set by his own history. He sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia for favorable winds; now, the wind has blown back.

Psychological Insight: Agamemnon represents the Inflated Patriarch. He walks on the “Red Carpet” (purple tapestries), an act of hubris reserved for gods. He is blind to the Shadow (Clytemnestra’s rage). In Jungian terms, when the masculine principle (Logos) becomes tyrannical and dismisses the feminine (Eros/Feeling), the feminine turns into a “Demon.”

Clytemnestra: The Terrible Mother

Clytemnestra is not just a villain; she is an archetype. She is the Terrible Mother who devours the husband. She kills Agamemnon in the bath—a place of vulnerability and cleansing. This symbolizes the regression to the womb, but a womb of death.

She justifies the murder as justice for Iphigenia. This is the Rationalization of the Shadow. The Shadow always has a “good reason” for its violence.

Cassandra: The Trauma of Insight

Cassandra is the most tragic figure. She sees the truth (prophecy) but is cursed never to be believed.

Clinical Relevance: Cassandra represents the Intuition of the traumatized individual. Trauma survivors often “see” the truth of a toxic family system but are gaslit or ignored by those around them. Her screams are the screams of the psyche trying to wake up the conscious mind.

II. The Libation Bearers: The Crisis of Conscience

The Dilemma of Orestes

Years later, Orestes returns. He is placed in a Double Bind (a “Catch-22”).

* If he does not kill his mother, the Furies of his father will drive him mad.

* If he does kill his mother, the Furies of his mother will drive him mad.

This is the essence of a Neurotic Conflict. The ego is trapped between two opposing imperatives (Instinct vs. Duty). There is no “clean” way out; he must choose the lesser evil and suffer the consequences.

Electra: The Animus Possession

Electra meets Orestes at the grave. She has kept the hate alive for years. She represents the Animus—the masculine spirit of action—that has been frozen in grief. She pushes Orestes to act because she cannot. She is the “Voice of the Dead Father” demanding retribution.

The Matricide

Orestes kills his mother. This is the Heroic Crime. In myth, the hero often has to “kill the mother” (sever the bond to the unconscious) to achieve independence. However, because this is a literal murder, it unleashes the Furies. Orestes does not feel triumph; he feels horror. This marks the beginning of his Nekyia (Night Sea Journey).

III. The Eumenides: The Transformation of Guilt

The Furies (The Old Law)

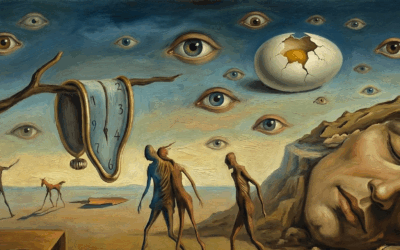

The Furies are ancient, chthonic goddesses. They are older than Zeus. They represent the Archaic Superego—the part of the psyche that punishes based on strict, biological laws (“You spilled kindred blood”). They do not care about intent; they care only about the act.

They hunt Orestes with the “stench of blood.” This is the Psychosomatic aspect of Guilt. Guilt is not just an idea; it is a physical sensation of being hunted.

Apollo (The New Law)

Orestes flees to Delphi. Apollo puts the Furies to sleep, but he cannot kill them.

Apollo represents Intellect and Reason. He argues that the father is the true parent, and the mother is just a vessel (a patriarchal defense). While Apollo protects Orestes, he cannot heal him. Logic alone cannot cure deep guilt.

The Trial on the Areopagus

The scene shifts to Athens. Athena establishes a court—the first jury trial.

This is the birth of the Democratic Ego. Instead of automatic punishment (Furies), we now have deliberation, evidence, and voting. The psyche moves from “Reaction” to “Reflection.”

Athena: The Transcendent Function

The jury splits 50/50. Athena casts the tie-breaking vote for acquittal.

Why? Because she was “born from the head of Zeus” (no mother). She represents the Androgynous Self that transcends the biological mother.

However, she does not banish the Furies. She invites them to stay. She transforms them into the Eumenides (“The Kindly Ones”). She gives them a home beneath the earth.

Crucial Insight: This is the Integration of the Shadow. Civilization cannot exist by repressing the instinctual Furies. It must honor them, give them a place, but not let them rule. The scary monsters of the unconscious become the “Protectors of the City” when they are respected.

IV. Clinical Relevance: Treating the Curse

The Oresteia is a map for treating Intergenerational Trauma.

1. Agamemnon Phase: The patient realizes they are living in a cursed system (Family Dysfunction).

2. Libation Bearers Phase: The patient takes action to break the cycle (Confrontation/Boundaries). This often leads to immense guilt (The Furies).

3. Eumenides Phase: The patient learns to live with the guilt not by repression, but by transformation. They build an “Inner Court” (Self-Compassion) that acquits them of the crime of wanting to be free.

Read About Other Classical Greek Plays and Their Influence on Depth Psychology

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

The House of Atreus Cycle

Elektra: The Grief That Freezes Time

Iphigenia in Aulis: The Sacrifice of the Daughter

Iphigenia in Tauris: The Healing of Orestes

The Feminine & The Shadow

The Bacchae: The Madness of the God

The Suppliants: The Right of Refuge

The Hero’s Journey

Oedipus Rex: The Trauma of Awakening

Oedipus at Colonus: The Redemption

Ajax: The Suicide of the Warrior

Philoctetes: The Wound and the Bow

Prometheus Bound: The Suffering God

Bibliography

- Aeschylus. The Oresteia. Translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Classics.

- Jung, C. G. (1956). Symbols of Transformation. Princeton University Press.

- Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype. Shambhala.

- Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press.

- Hillman, J. (2004). A Terrible Love of War. Penguin.

0 Comments