So different from the Midwest, where the possibilities sprawled bright and endless in every direction.

He wondered if people in the Himalayas and Andes were affected similarly.

Did they live in the passive voice, as if their lives were not really happening but instead were memories fixed and immutable?

-The World Made Straight, by Ron Rash

The Psychology of Language: How Ancient and Modern Languages Shape Thought and Emotion

Language is not merely a tool for communication; it is a powerful force that shapes our thoughts, emotions, and perceptions of the world around us. The psychology of language is a fascinating field that explores the complex interplay between linguistic structures, cultural values, and cognitive processes. By examining the linguistic features of ancient and modern languages, we gain valuable insights into how different societies and civilizations conceptualize reality and express their experiences.

The Power of Voice:

One of the most fundamental aspects of language is the use of active and passive voice. In his book “The World Made Straight,” author Ron Rash explores how the detachment of living in the mountains of Appalachian poverty can affect people’s sense of agency. He suggests that the passive voice, where actions happen to the subject rather than being actively initiated by them, reflects a perception of life as a series of immutable events beyond one’s control.

The choice between active and passive voice can significantly impact how we perceive responsibility and causality. In the active voice, the subject is the doer of the action, while in the passive voice, the subject is the recipient of the action. This subtle linguistic difference can shape our understanding of events and influence our emotional responses to them.

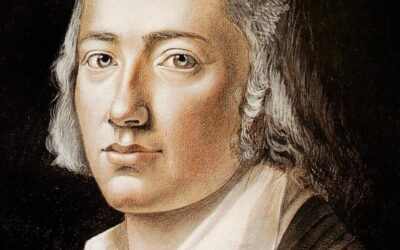

Language as the House of Being:

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger famously stated that “language is the house of being.” This profound idea suggests that language is not just a means of communication but the very framework through which we comprehend and make sense of the world. Language provides the structure for our thoughts and the basis for our understanding of reality.

Heidegger’s concept highlights the transformative power of language in shaping our experiences and molding our thinking. The words we use and the linguistic structures we employ determine what can be expressed and understood within the confines of a particular language. As a result, language has a profound impact on our cognitive processes and emotional experiences.

The Flexibility of English:

The English language is known for its flexibility and adaptability. Its relatively simple grammatical structure and modular nature allow for greater flexibility in word order compared to languages with more rigid structures and complex verb conjugations. This linguistic flexibility enables English speakers to express ideas and emotions with a wide range of nuances and emphases.

However, this flexibility can also make it easy to overlook the limitations and influences that other languages impose on their speakers’ psychology. Languages with more rigid structures or complex verb conjugations may shape thought and emotion in ways that are less apparent to English speakers.

Aztec Language and the Divine:

The Aztec language, Nahuatl, offers a fascinating example of how language can reflect a culture’s spiritual beliefs and practices. In Nahuatl, the term “Teotl” is used to refer to deities, gods, or sacred powers. This linguistic feature imbues actions, rituals, and interactions with the world with a sense of divine presence.

Nahuatl verbs often incorporate prefixes and suffixes that convey a sense of divine or sacred action. For example, verbs may include prefixes like “tlā-” (to give, to provide) or “yō-” (to go in search of) to indicate divine or sacred actions. This linguistic structure reinforces the idea that the Aztec world was permeated with the presence of the divine, shaping their perception of reality and their emotional experiences.

Native American Languages and Ownership:

Native American languages provide valuable insights into cultural perspectives on ownership and the relationship between humans and nature. Many Native American languages are verb-based, emphasizing actions and processes rather than static nouns and ownership. This linguistic structure reflects a worldview that prioritizes the dynamic interactions between humans and the natural world.

In some Native American languages, the concept of individual ownership is less prominent or even absent. Instead, the language may emphasize communal ties and relationships to the land. Speakers may use constructions that highlight the interconnectedness of all living beings and the environment, rather than asserting individual possession.

The absence of direct linguistic equivalents for the concept of “ownership” in some Native American languages challenges Western notions of property and dominion over nature. It reflects a cultural perspective that values harmony, respect, and coexistence with the natural world.

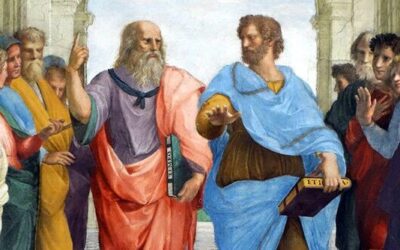

Greek and Roman Concepts of Time:

The ancient Greek and Roman languages offer contrasting perspectives on the nature of time and the role of human agency. Ancient Greeks believed in a circular nature of time and an inescapable thread of destiny set by nature. This worldview is reflected in their language, with complex verb tenses and aspects that convey a sense of repeated actions and cyclical events.

Greek philosophers developed specialized terminology to express their ideas about cyclical time, such as “panta rhei” (everything flows) and “ekpyrosis” (the cosmic conflagration and renewal). These concepts, embedded in the Greek language, reinforced the notion of a circular, ever-changing universe.

In contrast, the Roman language emphasizes accomplishment, technology, and the mastery of the natural world by humans. Latin vocabulary and writings often reflect a pragmatic approach to nature and the built environment. The Roman concept of fate (fatum) was less fatalistic than the Greek concept, allowing for the possibility of human agency and personal responsibility.

Latin has several tenses that imply responsibility and accomplishment, such as the passive periphrastic and the pluperfect tense. These linguistic features underscore the Roman belief in the importance of individual actions and their consequences.

Ancient Phoenician and Old Norse:

The ancient Phoenician script and the Old Norse language offer additional insights into the relationship between language and cultural values. The Phoenician script primarily consisted of consonants, with vowels often omitted, suggesting a pragmatic and concise approach to communication that reflected the Phoenicians’ trade-oriented culture.

Old Norse, on the other hand, was a storyteller’s language, with a rich system of verb tenses and a flexible word order that allowed for poetic creativity. The use of kennings, imaginative metaphors that replace literal words, reflects the Norse culture’s love for storytelling and the importance of narrative in their worldview.

Mandarin and the Universality of Knowledge: Mandarin Chinese presents unique challenges in the realm of citation and source attribution due to its complex writing system and the absence of clear distinctions between direct quotes and paraphrased content. This linguistic feature reflects a cultural difference in the understanding of the universality of knowledge.

To address these challenges and promote academic integrity, Chinese educational institutions have been working to integrate Western-style citation practices into their curriculum. This effort highlights the importance of understanding and bridging cultural differences in the pursuit of knowledge and the exchange of ideas.

: The psychology of language is a rich and complex field that illuminates the profound impact of linguistic structures on human thought, emotion, and perception. By exploring the linguistic features of ancient and modern languages, we gain valuable insights into the cultural values, priorities, and cognitive processes of different societies and civilizations.

From the power of active and passive voice in shaping our sense of agency to the influence of verb-based languages on our understanding of ownership and the natural world, language plays a crucial role in molding our experiences and shaping our realities.

As we navigate an increasingly interconnected world, understanding the psychological underpinnings of language becomes ever more important. By appreciating the diverse ways in which language shapes thought and emotion, we can foster greater empathy, understanding, and cooperation across cultures and civilizations.

Bibliography:

- Rash, R. (2012). The World Made Straight. Henry Holt and Company.

- Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, Language, Thought. Harper & Row.

- Whorf, B. L. (1956). Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT Press.

- Sapir, E. (1921). Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- Lockhart, J. (1992). The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford University Press.

- Basso, K. H. (1996). Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache. University of New Mexico Press.

- Homer. (1999). The Iliad. Translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Classics.

- Virgil. (2006). The Aeneid. Translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Classics.

- Sophocles. (1984). The Three Theban Plays: Antigone, Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus. Translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Classics.

- Byock, J. L. (1990). Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. University of California Press.

- Li, C. N., & Thompson, S. A. (1989). Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar. University of California Press.

Further Reading:

- Boroditsky, L. (2011). How Language Shapes Thought. Scientific American, 304(2), 62-65.

- Crystal, D. (2010). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge University Press.

- Deutscher, G. (2010). Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages. Metropolitan Books.

- Everett, D. L. (2008). Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle. Vintage.

- Pinker, S. (2007). The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature. Penguin Books.

- Slobin, D. I. (1996). From “Thought and Language” to “Thinking for Speaking”. In J. J. Gumperz & S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking Linguistic Relativity (pp. 70-96). Cambridge University Press.

- Tomasello, M. (2008). Origins of Human Communication. MIT Press.

- Wierzbicka, A. (1992). Semantics, Culture, and Cognition: Universal Human Concepts in Culture-Specific Configurations. Oxford University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell Publishing.

- Wolf, M. (2007). Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. HarperCollins.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

0 Comments