The Chiron Paradox

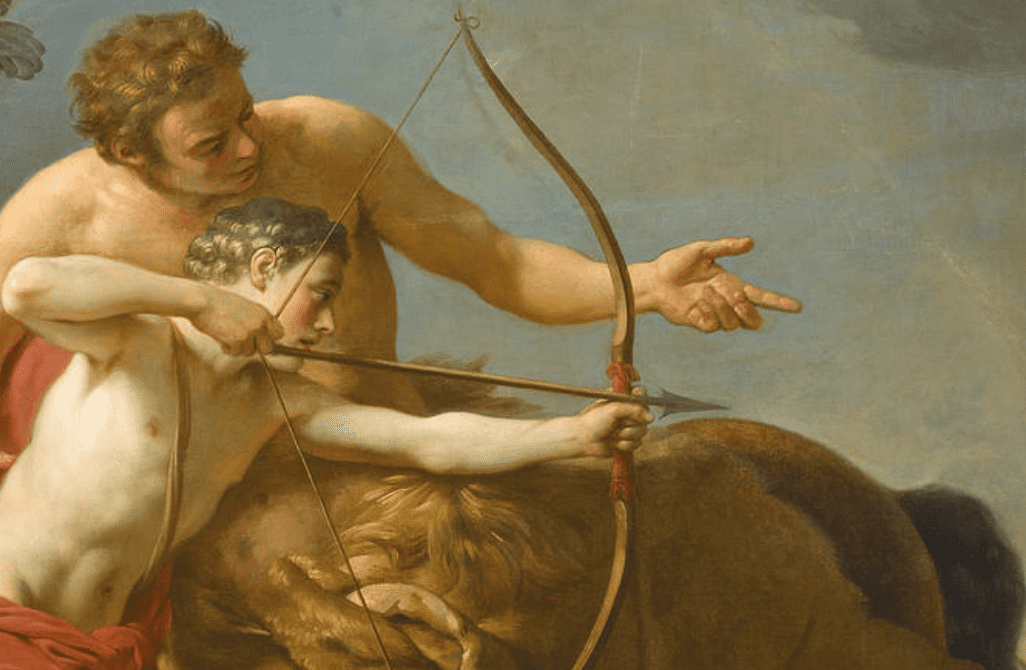

In the constellation of Greek mythology, few figures embody the paradox of human suffering and healing as profoundly as Chiron, the wounded healer. Unlike his brutish centaur kin, Chiron was wise, gentle, and skilled in the arts of medicine, music, and prophecy. Yet he carried within himself an unhealable wound—struck by a poisoned arrow, he lived in perpetual pain despite his vast knowledge of healing arts. This mythological figure serves as a powerful metaphor for a phenomenon deeply embedded in the helping professions: those who guide others through darkness often carry their own unhealed wounds, and therein lies both their greatest strength and most dangerous vulnerability.

The archetype of the wounded healer permeates the therapeutic landscape, manifesting in the countless professionals who entered their fields not despite their wounds, but because of them. This essay explores the complex interplay between personal trauma and professional calling, the neurological overlap between intuition and trauma responses, and the critical importance of distinguishing between genuine therapeutic insight and unconscious projection of one’s own unresolved pain.

The Neurological Confluence: Where Intuition Meets Trauma

Modern neuroscience has revealed a fascinating and troubling reality: the brain regions associated with intuitive knowing significantly overlap with those activated by trauma responses. The limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, plays crucial roles in both intuitive processing and trauma storage. This neurological confluence creates a profound challenge for helping professionals who rely on their intuitive capacities while potentially carrying unresolved trauma.

The right hemisphere of the brain, dominant in processing emotional nuance, body sensations, and implicit memory, serves as the seat of both intuitive wisdom and traumatic imprints. When a therapist experiences a “gut feeling” about a client’s underlying issues, they may be accessing genuine intuitive insight—or they may be experiencing an activation of their own trauma-based patterns. The challenge lies in developing the discernment to distinguish between these two sources of information.

This neurological overlap explains why so many wounded individuals feel called to healing professions. Their heightened sensitivity to emotional undercurrents, developed as a survival mechanism in challenging childhood environments, can become a professional asset. However, without conscious awareness and ongoing self-work, this same sensitivity can lead to projection, countertransference, and the unconscious reenactment of personal trauma dynamics in the therapeutic space.

The Drama of the Gifted Child: When Healers Emerge from Wounding

Alice Miller’s seminal work, “The Drama of the Gifted Child,” illuminates how many individuals who become therapists, counselors, and healers were the emotionally attuned children in their families of origin. These “gifted” children—gifted not necessarily in intellectual terms but in emotional sensitivity—often served as the emotional regulators for their families, developing hypervigilance to others’ needs while learning to suppress their own.

Miller observed that these children, having learned to read micro-expressions, voice tones, and atmospheric shifts with uncanny accuracy, often grew up to become the very professionals tasked with healing others. Yet beneath their competent exterior often lies a child who never received the mirroring, validation, and unconditional acceptance they now strive to provide for others. This creates what Miller termed “the helper syndrome”—a compulsive need to heal others as an unconscious attempt to heal oneself.

The tragedy Miller identifies is that many therapists enter their training and practice without having addressed their own narcissistic wounds—the early injuries to the self that occurred when their authentic feelings and needs were not adequately recognized or validated. These professionals may possess exceptional clinical skills and theoretical knowledge, yet remain blind to how their own unmet needs influence their therapeutic relationships.

The MBTI Connection: Intuitive Feelers and the Helping Imperative

Within the framework of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), certain personality types—particularly those with Intuitive Feeling (NF) preferences—show marked overrepresentation in helping professions. INFJs, INFPs, ENFJs, and ENFPs frequently populate the ranks of therapists, counselors, teachers, nurses, and clergy. This pattern is not coincidental but speaks to how certain temperaments may be both shaped by early experiences and drawn to healing work.

Intuitive Feelers often report feeling “different” from an early age, possessing a depth of emotional experience and concern for meaning that set them apart from their peers. Many describe childhoods marked by a sense of being outsiders, too sensitive for their environments, or burdened by an awareness of suffering that others seemed not to perceive. These early experiences of differentness, often accompanied by various forms of wounding, can create both the motivation and the capacity for healing work.

The danger emerges when these naturally empathic individuals mistake their trauma-informed hypervigilance for pure intuition. An INFJ therapist who grew up in an alcoholic household may possess an uncanny ability to detect subtle signs of addiction—but may also project addiction dynamics onto situations where they don’t exist. An ENFP teacher who experienced emotional neglect might be extraordinarily attuned to students’ emotional needs while unconsciously using their classroom to meet their own unmet needs for connection and validation.

The Double-Edged Sword: Wounds as Windows and Walls

Childhood wounds can indeed provide unique insights into human suffering and systemic dysfunction. The child who grows up in a dysfunctional family system often develops what family systems theorists call a “meta-position”—the ability to observe the system from outside while still being within it. This perspective, born from the necessity of psychological survival, can evolve into a sophisticated capacity for systems analysis and pattern recognition.

Many effective therapists credit their own difficult experiences with providing them insider knowledge of trauma, addiction, depression, or family dysfunction. A therapist who has navigated their own journey through grief may possess a depth of understanding that no textbook could provide. A counselor who has wrestled with addiction may recognize the subtle self-deceptions and defensive patterns that others might miss.

However, these same wounds can become walls that prevent genuine healing—both for the therapist and their clients. When a helper has not adequately processed their own trauma, they may unconsciously use their professional role to maintain distance from their pain. The therapeutic relationship can become a stage for playing out the helper’s unresolved dynamics: the neglected child finally being needed, the powerless child finally having influence, the unseen child finally being recognized as special.

The Projection Trap: When We Give Others Our Own Medicine

Perhaps the most insidious danger facing wounded healers is the tendency to project their own healing needs onto their clients. This projection can take many forms, from subtle influences on treatment direction to more overt boundary violations. A therapist who has not grieved their own losses may push clients toward grief work prematurely. A counselor struggling with unacknowledged anger might either avoid anger in their clients or see it everywhere.

This projection operates largely outside conscious awareness, making it particularly dangerous. The therapist genuinely believes they are serving their client’s best interests, unaware that they are unconsciously attempting to heal themselves through their client’s journey. This not only impedes the client’s authentic healing process but also prevents the therapist from addressing their own wounds directly.

The phenomenon extends beyond individual therapy relationships to influence entire theoretical orientations and treatment modalities. How many therapeutic approaches have been developed by wounded healers attempting to systematize their own healing journey? While personal experience can inform valuable insights, the universalization of one’s own healing path can become a Procrustean bed, forcing all clients to fit the mold of the therapist’s own journey.

The Systems Perspective: Seeing Clearly While Remaining Blind

One of the paradoxes of the wounded healer is their capacity to perceive systemic dysfunction with crystal clarity while remaining blind to their own participation in similar patterns. The family therapist who can map complex multigenerational patterns in client families may be oblivious to how they’re repeating their own family dynamics with colleagues. The organizational consultant who identifies toxic workplace cultures may be recreating familiar dysfunction in their own practice.

This selective blindness often stems from the psychological defenses that allowed survival in difficult childhood environments. Dissociation, intellectualization, and compartmentalization—adaptive strategies in traumatic situations—can persist into professional life, creating split awareness where insight about others coexists with denial about oneself.

The ability to analyze systems from the outside, developed as a survival strategy in dysfunctional childhood environments, becomes both a professional strength and a personal limitation. The therapist remains the eternal observer, never fully entering their own healing process with the same vulnerability they encourage in their clients.

The Integration Imperative: Healing the Healer

The path forward requires a radical commitment to ongoing self-examination and healing for those in helping professions. This is not a luxury or an optional addition to professional development—it is an ethical imperative. Just as Chiron’s wound never fully healed but became the source of his wisdom, helping professionals must maintain an ongoing relationship with their own wounding, neither denying it nor being consumed by it.

This integration process involves several key components:

Continuous Self-Reflection: Regular supervision, peer consultation, and personal therapy should be viewed not as signs of professional weakness but as essential maintenance for the therapeutic instrument—the self. The therapist must be willing to examine their motivations, reactions, and blind spots with the same courage they ask of their clients.

Somatic Awareness: Given the body’s role in storing trauma and generating intuitive information, helping professionals must develop sophisticated somatic awareness. This involves learning to distinguish between bodily sensations arising from genuine intuitive knowing versus those signaling personal trauma activation.

Boundaries and Self-Care: The wounded healer must learn to establish and maintain boundaries that protect both themselves and their clients from the unconscious merging that trauma can create. This includes recognizing limits, taking breaks, and engaging in activities that nourish the self beyond the professional role.

Community and Connection: Isolation intensifies the wounded healer’s dilemma. Building genuine peer relationships, where vulnerability can be shared without professional facades, provides essential reality-checking and emotional support.

Spiritual or Existential Grounding: Many wounded healers find that connecting with something larger than themselves—whether through formal spiritual practice, nature, art, or philosophy—provides perspective and renewal that prevents professional burnout and personal stagnation.

The Shadow Side: When Wounded Healers Become Unconscious Con Artists

The wounded healer archetype contains within it a darker possibility that must be acknowledged: the unconscious con artist who uses the helping profession to avoid genuine healing while extracting validation, power, or resources from others. These individuals, often unaware of their own motivations, create elaborate psychological constructions that allow them to maintain contradictory narratives about themselves.

These practitioners simultaneously present themselves as both possessing ultimate potential and being ultimate victims—they’ve accomplished everything yet have nothing to show for it. They speak eloquently about transformation while their own lives remain static. They collect credentials, certifications, and titles like talismans against their own emptiness, seeking the feeling of accomplishment without engaging in the actual work of growth. The tragedy is that many genuinely believe their own narratives, having learned in childhood that they could manipulate systems and authority figures by being the exception to the rules.

Often, these individuals develop obscure personal moralities that justify their behavior. Like financial con artists who create elaborate rationalizations for theft, therapeutic con artists develop complex philosophical frameworks that explain why traditional ethics don’t apply to them. They may charge excessive fees while claiming spiritual poverty, violate boundaries while preaching about safety, or remain perpetually in crisis while positioning themselves as guides for others’ stability.

A telling sign is their tendency to over-relate to children and animals while struggling with adult relationships. They find comfort in relationships where projection is easy and challenge is minimal. They may claim their work is “for the children” or surround themselves with pets who “understand them better than people.” This preference for beings who cannot articulate disagreement or establish boundaries reveals their inability to engage in genuine mutual relationships.

These patterns often originate in childhoods where they learned to navigate dysfunction through manipulation rather than authentic adaptation. Perhaps they were the “special” child who could charm an alcoholic parent out of rage, or the “gifted” one who learned that intellectual performance could substitute for emotional connection. They discovered early that stepping outside systems through exception-making was easier than doing the work of genuine participation.

The hypochondriac tendency—inventing or exaggerating trauma, creating dramatic narratives about their past that shift depending on the audience—serves multiple functions. It provides explanation for their failures, elicits caregiving from others, and maintains their special status as one who has suffered uniquely. Yet when examined closely, these stories often contain logical impossibilities, parallel realities that cannot coexist.

Most insidiously, these wounded healers who refuse their own healing create a particularly toxic form of countertransference. They unconsciously seek clients who will mirror their own stuckness, creating therapeutic relationships that revolve around potential rather than progress. Two years, five years, a decade passes with the same conversations, the same crises, the same promises of breakthrough that never materialize. The therapist and client become locked in a dance of mutual enabling, each providing the other with an excuse to avoid genuine change.

The Ongoing Journey: Wounded Healing as a Developmental Process

Perhaps the ultimate wisdom lies in recognizing that the journey from wounded to healer is not a destination but an ongoing process. The goal is not to become an unwounded healer—such a person would likely lack the depth of understanding that comes from wrestling with one’s own darkness. Rather, the aim is to become a conscious wounded healer, one who knows their wounds intimately enough to prevent them from unconsciously driving the therapeutic process.

This consciousness requires accepting that healing is not a linear process with a clear endpoint. Like Chiron, who continued teaching and healing despite his permanent wound, helping professionals must learn to work skillfully with their ongoing vulnerabilities while not allowing them to dominate their professional practice.

The wounded healer who has done their own work possesses a unique gift: the ability to hold space for others’ pain without being consumed by it, to recognize patterns without projecting them, and to offer hope born from genuine experience rather than theoretical understanding. They can accompany clients into the darkest places because they have made that journey themselves and returned, not unscathed but transformed.

The Alchemy of Conscious Wounding

The myth of Chiron offers a final wisdom: when Zeus finally allowed him to die and transformed him into a constellation, Chiron’s wound became a source of guidance for navigation. Similarly, when helping professionals consciously integrate their wounds, these experiences can become constellations that guide both themselves and others through the darkness.

The challenge facing contemporary helping professions is to create training programs, professional cultures, and support systems that acknowledge and work with the wounded healer reality rather than denying it. This means normalizing ongoing personal work, teaching discrimination between intuition and projection, and fostering communities where vulnerability is seen as strength rather than liability.

As we move forward, may we honor both the gifts and dangers of the wounded healer archetype. May we recognize that our wounds, consciously held and continually examined, can become sources of wisdom without becoming prisons of projection. And may we always remember that the most powerful medicine we can offer others is our own ongoing commitment to healing, integration, and conscious awareness.

In the end, perhaps the greatest service wounded healers can provide is modeling what it means to be fully human: flawed and wise, vulnerable and strong, wounded and healing. By embracing this paradox with consciousness and commitment, we transform Chiron’s curse into a blessing—not just for ourselves, but for all those whose lives we touch in our journey toward wholeness.

Bibliography

Clarkson, P. (1995). The Therapeutic Relationship. London: Whurr Publishers.

Conti-O’Hare, M. (2002). The Nurse as Wounded Healer: From Trauma to Transcendence. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Dunne, C. (2000). Carl Jung: Wounded Healer of the Soul. New York: Parabola Books.

Groesbeck, C. J. (1975). “The Archetypal Image of the Wounded Healer.” Journal of Analytical Psychology, 20(2), 122-145.

Guggenbuhl-Craig, A. (1971). Power in the Helping Professions. Dallas: Spring Publications.

Jackson, S. W. (2001). “The Wounded Healer.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75(1), 1-36.

Jung, C. G. (1951). “Fundamental Questions of Psychotherapy.” In The Practice of Psychotherapy, CW 16. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kirmayer, L. J. (2003). “Asklepian Dreams: The Ethos of the Wounded-Healer in the Clinical Encounter.” Transcultural Psychiatry, 40(2), 248-277.

Miller, A. (1979). The Drama of the Gifted Child. New York: Basic Books.

Nouwen, H. J. M. (1972). The Wounded Healer: Ministry in Contemporary Society. New York: Doubleday.

Remen, R. N. (1996). Kitchen Table Wisdom: Stories That Heal. New York: Riverhead Books.

Sedgwick, D. (1994). The Wounded Healer: Countertransference from a Jungian Perspective. London: Routledge.

Stone, M. H. (2008). “The Wounded Healer: A Historical and Ethical Perspective.” Journal of Medical Biography, 16(1), 36-39.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

Wolgien, C. S., & Coady, N. F. (1997). “Good Therapists’ Beliefs About the Development of Their Helping Ability: The Wounded Healer Paradigm Revisited.” The Clinical Supervisor, 15(2), 19-35.

Zerubavel, N., & Wright, M. O. D. (2012). “The Dilemma of the Wounded Healer.” Psychotherapy, 49(4), 482-491.

0 Comments