For residents of Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills, Homewood, and greater Birmingham, one of our most defining institutions offers an unexpected lesson about becoming who we never planned to be.

The Institution That Is Younger Than Your Parents

Here is a fact that surprises almost everyone who learns it. The University of Alabama at Birmingham, the institution that dominates our downtown skyline, employs more people than any other organization in the state, and generates over twelve billion dollars in annual economic impact, did not exist as an independent university until 1969.

That date is worth sitting with. 1969 means UAB is only fifty-five years old. The Beatles were still together when UAB became a university. The first human beings walked on the moon the same summer that Joseph F. Volker was named UAB’s first president. Many residents of Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills, and Homewood are older than the university that defines so much of Birmingham’s modern identity.

And perhaps most remarkably, UAB’s emergence as an independent institution was not the result of careful long-term planning. It was something closer to an accident.

From Extension Center to Economic Engine

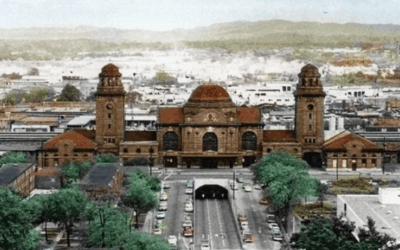

The story begins not with a grand vision but with a modest extension center. In 1936, the University of Alabama opened a small Birmingham outpost where local residents could take evening courses and earn credits toward Tuscaloosa degrees. It was a satellite operation, administratively subordinate and geographically distant from the real university sixty miles to the southwest.

Separately, the Medical College of Alabama had been relocated to Birmingham in 1945, creating a medical center that was also technically part of the Tuscaloosa campus. The two Birmingham operations existed side by side for years without formal connection.

In 1954, the Extension Center moved to a location adjacent to the Medical Center, and the components finally shared physical proximity. But administrative merger did not come until November 1966, when University of Alabama President Frank A. Rose designated all Birmingham operations as the “University of Alabama in Birmingham.” Even then, UAB remained a branch campus. Degrees were granted through Tuscaloosa. The Birmingham operation was expected to remain a supporting player.

What nobody anticipated was how quickly the Birmingham campus would outgrow its intended role.

The Accidental Independence of 1969

On June 16, 1969, Governor Albert P. Brewer announced something that changed Birmingham’s trajectory. The University of Alabama System would be reorganized into three autonomous campuses. Tuscaloosa, Birmingham, and Huntsville would each have their own president reporting directly to the Board of Trustees. UAB was no longer a branch. It was an independent university.

The decision emerged from practical necessity rather than grand planning. Birmingham’s population and economic importance had grown beyond what a satellite campus could serve. The medical center was developing national significance. Local business leaders and healthcare professionals wanted educational opportunities that a branch campus could not provide. The pressure built until separation became the only workable solution.

Joseph F. Volker, who had been serving as vice president for Birmingham Affairs, became UAB’s first president. By 1976, just seven years later, UAB was Birmingham’s largest employer. The institution that had been an afterthought to Tuscaloosa had become the economic engine of Alabama’s largest city.

What Birmingham Assumes About UAB

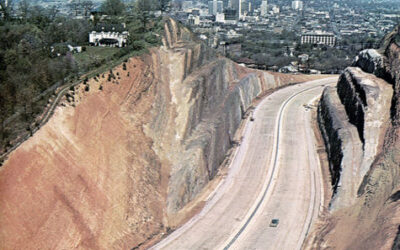

Drive through downtown Birmingham today and UAB’s presence is inescapable. Hospital towers rise above the medical district. University buildings stretch across dozens of city blocks. The Blazers compete in eighteen NCAA sports. Research facilities attract scientists from around the world.

Visitors and longtime residents alike tend to assume this institutional presence reflects deep historical roots. Surely an operation of this scale must have been planned for generations. Surely the founders of Birmingham envisioned a great research university anchoring their city.

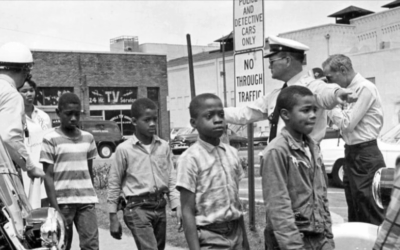

They did not. Birmingham existed for over a century before UAB emerged. The iron and steel barons who built Mountain Brook and the original downtown mansions never imagined that healthcare and education would eventually dwarf heavy industry. The families who established Vestavia Hills and Homewood in the mid-twentieth century watched UAB grow from a small extension center into an institution larger than anything the steel mills had produced.

UAB became what it is not because someone planned it but because circumstances converged and opportunities were seized.

The Psychology of Unplanned Becoming

In therapeutic work with Birmingham residents, I frequently encounter a particular form of suffering. Clients feel trapped by the identities they were assigned early in life. They were supposed to be the responsible one, the successful one, the caretaker, the achiever. They were expected to follow certain paths toward certain outcomes. And when their actual development diverged from these expectations, they experienced confusion, guilt, or a sense of having failed at being themselves.

UAB’s history offers a different model. Here is an institution that was never supposed to become what it became. It was designed to be a modest extension center, a support operation for the real university in Tuscaloosa. Nobody drew up plans for a research powerhouse. Nobody envisioned fifty-three thousand employees and billions in economic impact. The institution simply grew in response to circumstances, seized opportunities that presented themselves, and eventually became something its founders could not have imagined.

This is not a failure of planning. This is the natural process of emergence. UAB did not betray its original identity by becoming a major research university. It discovered capacities that had not yet manifested and allowed them to develop.

The Burden of Early Definition

For residents of Mountain Brook, Homewood, and Vestavia Hills who grew up with clear expectations about who they would become, UAB’s story may feel both liberating and unsettling. If even institutions can radically exceed their original definitions, what does that mean for individuals?

Developmental psychology suggests that early identity formation often serves protective functions. Children need stable frameworks for understanding themselves. “I am the smart one” or “I am the athletic one” or “I am the helpful one” provides orientation in a complex social world. These identities are not imposed maliciously. They emerge from family systems doing their best to organize and nurture their members.

But identities that serve children can constrain adults. The responsible one may never learn to ask for help. The successful one may collapse under the weight of maintaining an image. The caretaker may lose contact with their own needs entirely. The identity that once provided security becomes a prison.

UAB could have remained an extension center. The original identity was functional and served legitimate purposes. But remaining confined to that definition would have prevented Birmingham from becoming what it is today. Sometimes outgrowing our assigned roles is not betrayal but development.

The Anxiety of Becoming Something New

Growth is not always comfortable. When UAB separated from Tuscaloosa in 1969, there must have been uncertainty about whether the young institution could survive on its own. New presidents were appointed. New administrative structures were developed. Accreditation had to be established independently. The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools did not grant UAB full accreditation as an independent institution until 1971.

In therapeutic work, I often witness similar anxiety when clients begin to grow beyond their established identities. They worry about abandoning who they have been. They fear disappointing people who expect the familiar version. They question whether the emerging self is authentic or fraudulent.

These concerns are understandable but often misplaced. UAB did not become inauthentic by growing into a research university. It became more fully itself. The capacities that enabled its expansion were always present in latent form. The medical center’s research excellence, the extension center’s service to working professionals, the institutional culture of striving, these elements simply needed the right conditions to flourish.

The same may be true for individuals who find themselves becoming something they never planned. The emerging self is not an imposter. It is a development.

Practical Applications for Residents of the Birmingham Area

For those seeking therapy in Mountain Brook, Homewood, Vestavia Hills, or Birmingham proper, UAB’s accidental founding offers several invitations for reflection.

First, consider what identities you were assigned early in life and whether they still serve you. These definitions may have been accurate descriptions of childhood capacities without being fixed limits on adult development. The extension center was a real and valuable thing. But it was not the only thing the Birmingham operation could become.

Second, notice where you may be constraining yourself to match expectations that no longer fit. Perhaps your family expected you to enter a particular profession, maintain a particular image, or fulfill a particular role. Perhaps you have continued performing that identity long past the point of authentic alignment. UAB’s independence came when the constraints of the branch campus model simply could not contain the institution’s actual development. Sometimes our own growth forces similar reckonings.

Third, recognize that emergence takes time and often involves periods of uncertainty. UAB did not become a major research university overnight. The first years of independence required building new structures, establishing credibility, and developing capacities that had been latent under the branch campus system. Personal development follows similar patterns. We do not become our fuller selves in a single breakthrough moment. We grow incrementally, often with significant anxiety about whether the growth is legitimate.

The City That Grew Up With Its University

Birmingham and UAB developed together in ways that neither could have anticipated. The steel industry that defined the city’s early identity gave way to healthcare and education as primary economic drivers. The neighborhoods of Mountain Brook and Vestavia Hills that were built for industrial executives now house healthcare professionals, researchers, and educators. Homewood’s commercial district serves a population whose economic life is increasingly tied to the university and its hospital system.

Neither the city nor the university planned this transformation. Both simply responded to changing circumstances, seized emerging opportunities, and became what the situation allowed.

For Birmingham residents wrestling with their own identity development, this parallel may be instructive. We do not control all the forces that shape our becoming. Economic shifts, family changes, health events, and countless other factors influence who we have the opportunity to become. What we can control is our response to these circumstances and our willingness to grow when growth becomes possible.

The Institution That Proves Late Starts Are Possible

UAB is only fifty-five years old. In the world of major research universities, this is extraordinarily young. Institutions like Harvard, Yale, and the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa measure their histories in centuries. UAB measures its in decades.

And yet UAB has achieved research prominence, athletic success, and economic impact that rival institutions with far longer pedigrees. The university does not apologize for its late start. It does not pretend to be older than it is. It simply does the work and lets the results speak.

For Birmingham residents who feel they started late on personal development, career changes, therapeutic growth, or any other transformation, UAB’s trajectory may offer encouragement. Late starts are possible. Rapid development can follow long periods of latency. The absence of a distinguished past does not prevent a significant future.

The institution that was not supposed to be a university at all is now the largest employer in Alabama. Something similar may be possible for those who feel confined by their own histories.

If you are seeking psychotherapy services in the Birmingham area, including Homewood, Vestavia Hills, and Mountain Brook, and would like to explore issues related to identity, personal development, or outgrowing the roles you were assigned, please contact Taproot Therapy Collective to schedule a consultation.

0 Comments