Have you ever worked with a client who seems absolutely unable to see things any other way than their own? Someone who follows the same routines religiously and falls apart when something unexpected happens? Or maybe someone who insists there’s only one right way to do things and can’t understand why others don’t see it? You’re probably dealing with cognitive rigidity, and it’s one of the most challenging issues we face as therapists.

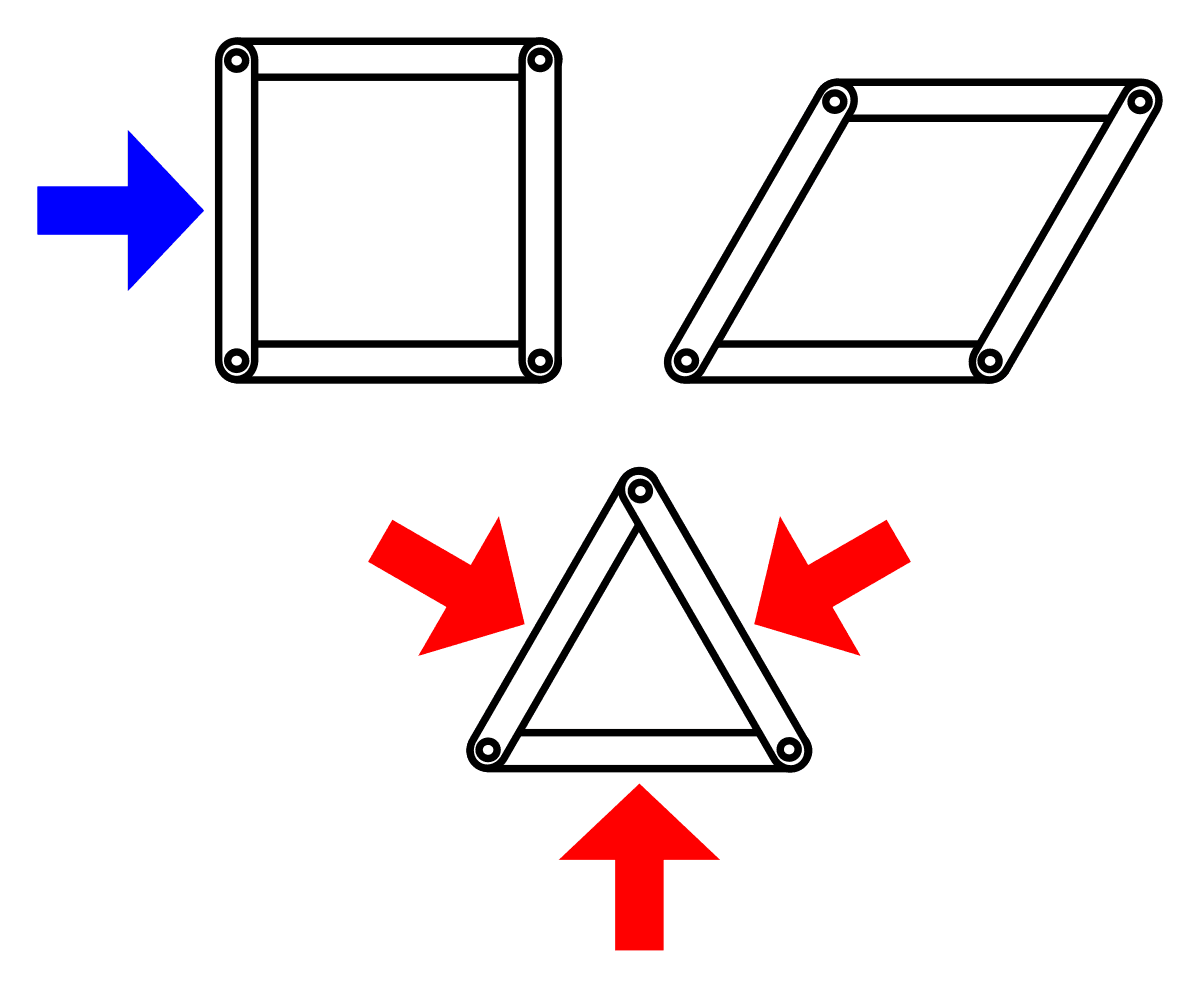

Cognitive rigidity isn’t just being stubborn or set in your ways. It’s a genuine difficulty in adapting thoughts and behaviors when situations change. The person’s brain literally struggles to shift gears, to let go of one way of thinking and try another. They get stuck applying the same rules and strategies over and over, even when those strategies clearly aren’t working anymore. It’s like their mind is a train that can only run on one track, unable to switch to a different route even when the current one leads nowhere.

The fascinating thing is that this isn’t simply a personality trait or a choice. Brain imaging studies show us that people with severe cognitive rigidity have measurable differences in their prefrontal cortex, the brain region that handles what we call executive functions. These are the high-level abilities that let us plan, adapt, switch between tasks, and see things from different perspectives. When this system isn’t working well, the person genuinely cannot easily shift their thinking. It’s not that they won’t change; in many cases, they literally can’t without significant support.

But here’s where it gets really interesting from a clinical perspective. For most people with cognitive rigidity, their inflexibility serves a purpose. It’s often a coping mechanism for managing overwhelming anxiety. When your brain struggles to handle uncertainty and change, creating rigid routines and strict rules provides a sense of safety and predictability. The world feels less chaotic when you know exactly what to expect and exactly what to do. The rigidity isn’t the primary problem; it’s actually their solution to a deeper problem of feeling overwhelmed by a world that feels unpredictable and unmanageable.

This shows up differently depending on the person’s underlying condition. In autism, you see an intense insistence on sameness. The person might need to take the exact same route to work every day, eat the same foods prepared the same way, or have a complete meltdown if their schedule changes unexpectedly. For them, these routines are essential scaffolding that makes an overwhelming sensory and social world manageable. The rigidity directly serves to regulate their anxiety.

In ADHD, the rigidity looks different. It’s less about wanting sameness and more about the brain’s fundamental difficulty with transitions. People with ADHD often get stuck in hyperfocus and become genuinely distressed when forced to switch tasks. They might abandon projects entirely when they hit an obstacle rather than trying a different approach. Their brain’s executive function system struggles with the mechanics of shifting attention and strategy, like trying to change gears with a broken clutch.

With personality disorders like OCPD, the rigidity becomes part of how the person sees themselves. They genuinely believe their way is the right way, that their perfectionism and high standards are virtues rather than problems. They can’t delegate tasks unless others do things exactly their way, and they get so caught up in details and rules that they lose sight of what actually matters. Unlike someone with OCD who feels tormented by their symptoms, someone with OCPD often doesn’t see anything wrong with their approach to life.

For trauma survivors, rigidity often develops as a protective strategy. When you’ve lived through experiences where the world felt dangerous and unpredictable, controlling everything you possibly can becomes a way to feel safe. Any deviation from the plan, any mistake, feels like it could lead to catastrophe because in their past, it sometimes did. The rigidity is their attempt to never be caught off guard again.

One of the biggest challenges we face in treating cognitive rigidity is that many clients don’t recognize it as a problem. This lack of insight can have different causes. Sometimes it’s neurological, where actual brain differences mean the person cannot perceive that they have difficulties. They’re not in denial; their brain literally doesn’t register the problem. Other times it’s psychological, where acknowledging the problem would be too threatening to their sense of self or their feeling of safety.

So how do we actually help these clients? The research shows us that we can’t just charge in and try to fix their rigid thinking directly. That approach almost always fails and often damages the therapeutic relationship. Instead, we need to understand what function the rigidity serves for this particular person and work from there.

The most effective approach usually starts with building a genuine connection without trying to change anything. Using motivational interviewing techniques, we explore the person’s own perspective and values without judgment. We listen for any hint of ambivalence, any suggestion that their rigidity might be costing them something they care about. Maybe they mention wishing they had more time with their kids, or feeling frustrated that their relationships keep failing. These small openings are where change becomes possible.

Once we have a solid therapeutic relationship, we can start introducing the idea that their struggles might have a neurobiological basis. Explaining how the brain works, how executive functions operate, and why some brains struggle more with flexibility than others can be incredibly powerful. It reframes their difficulties from character flaws to understandable challenges based on how their particular brain works. This reduces shame and makes it safer to explore change.

Different therapeutic approaches work better for different types of rigidity. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy works well when the person has specific, testable beliefs that maintain their rigidity. We can design behavioral experiments where they test out what actually happens when they break their rules in small, safe ways. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is better when the rigidity is tied up with their identity and they use it to avoid uncomfortable feelings. Instead of trying to eliminate rigid thoughts, we help them see thoughts as just thoughts rather than commands that must be obeyed. Metacognitive Therapy targets the beliefs people have about their own thinking, like believing they must worry constantly to be prepared for problems.

When traditional therapy isn’t enough, which happens more often than we’d like with severe rigidity, there are emerging interventions that can help. Cognitive training programs can directly exercise and strengthen the brain’s flexibility systems through repeated practice. Brain stimulation techniques like TMS can modulate the activity in rigid neural circuits, making the brain more receptive to change. In some cases, carefully controlled psychedelic-assisted therapy can create temporary windows of enhanced neuroplasticity where old patterns can finally shift.

The key to remember is that we need to adapt our approach based on what’s driving each person’s rigidity. For autistic clients, we prioritize reducing anxiety and making change feel safe and predictable. For clients with ADHD, we provide external structure and break everything into manageable steps. For those with personality-based rigidity, we avoid power struggles about who’s right and instead explore how their rigidity conflicts with their own stated values.

Throughout all of this, we as therapists must model the flexibility we’re trying to help our clients develop. When our approach isn’t working, we need to be willing to try something different. When clients resist or disagree, we need to see that as information rather than defiance. The therapeutic relationship itself becomes a place where the client can experience flexibility as something safe rather than threatening.

Working with cognitive rigidity requires patience, creativity, and a willingness to think outside our own therapeutic boxes. These clients aren’t choosing to be difficult. Their rigidity developed for good reasons and has probably protected them in important ways. Our job isn’t to take away their coping mechanism but to help them develop new, more flexible ways of creating safety and managing their world. When we can do that successfully, we open up possibilities for them that rigidity had closed off, helping them discover that flexibility, not control, is what actually makes life manageable.

0 Comments