“The years, of which I have spoken to you, when I pursued the inner images, were the most important time of my life. Everything else is to be derived from this. It began at that time, and the later details hardly matter anymore. My entire life consisted in elaborating what had burst forth from the unconscious and flooded me like an enigmatic stream and threatened to break me. That was the stuff and material for more than only one life. Everything later was merely the outer classification, the scientific elaboration, and the integration into life. But the numinous beginning, which contained everything, was then.”\

― C.G. Jung, preface for The Red Book: Liber Novus

James Hillman: I was reading about this practice that the ancient Egyptians had of opening the mouth of the dead. It was a ritual and I think we don’t do that with our hands. But opening the Red Book seems to be opening the mouth of the dead.

Sonu Shamdasani: It takes blood. That’s what it takes. The work is Jung’s `Book of the Dead.’ His descent into the underworld, in which there’s an attempt to find the way of relating to the dead. He comes to the realization that unless we come to terms with the dead we simply cannot live, and that our life is dependent on finding answers to their unanswered questions.

- Lament for the Dead, Psychology after Jung’s Red Book (2013) Pg. 1

Begun in 1914, Swiss psychologist Carl Jung’s The Red Book lay dormant for almost 100 years before its eventual publication. Opinions are divided on whether Jung would have published the book if he had lived longer. He did send drafts to publishers early in life but seemed in no hurry to publish the book despite his advancing age. Regardless, it was of enormous importance to the psychologist, being shown to only a few confidants and family members. More importantly, the process of writing The Red Book was one of the most formative periods of Jung’s life. In the time that Jung worked on the book he came into direct experience with the forces of the deep mind and collective unconscious. For the remainder of his career he would use the experience to build concepts and theories about the unconscious and repressed parts of the human mind.

In the broadest sense, Jungian psychology has two goals.

and

Jungian psychology is about excavating the most repressed parts of self and learning to hold them so that we can know exactly who and what we are. Jung called this process individuation. Jungian psychology is not, and should not be understood as, an attempt to create a religion. It was an attempt to build a psychological container for the forces of the unconscious. While not a religion, it served a similar function as a religion. Jungian psychology serves as both a protective buffer and a lens to understand and clarify the self. Jung described his psychology as a bridge to religion. His hope was that it could help psychology understand the functions of the human need for religion, mythology and the transcendental. Jung hoped that his psychology could make religion occupy a healthier, more mindful place in our culture by making the function of religion within humanity more conscious.

Jung did not dislike religion. He viewed it as problematic when the symbols of religion became concretized and people took them literally. Jungian psychology itself has roots in Hindu religious traditions. Jung often recommended that patients of lapsed faith return to their religions of origin. He has case studies encouraging patients to resume Christian or Muslim religious practices as a source of healing and integration. Jung did have a caveat though. He recommended that patients return to their traditions with an open mind. Instead of viewing the religious traditions and prescriptive lists of rules or literal truths he asked patients to view them as metaphors for self discovery and processes for introspection. Jung saw no reason to make religious patients question their faith. He did see the need for patients who had abandoned religion to re-examine its purpose and function.

The process of writing The Red Book was itself a religious experience for Jung. He realized after his falling out from Freud, that his own religious tradition and the available psychological framework was not enough to help him contain the raw and wuthering forces of his own unconscious that were assailing him at the time. Some scholars believe Jung was partially psychotic while writing The Red Book, others claim he was in a state of partial dissociation or simply use Jung’s term “active imagination”.

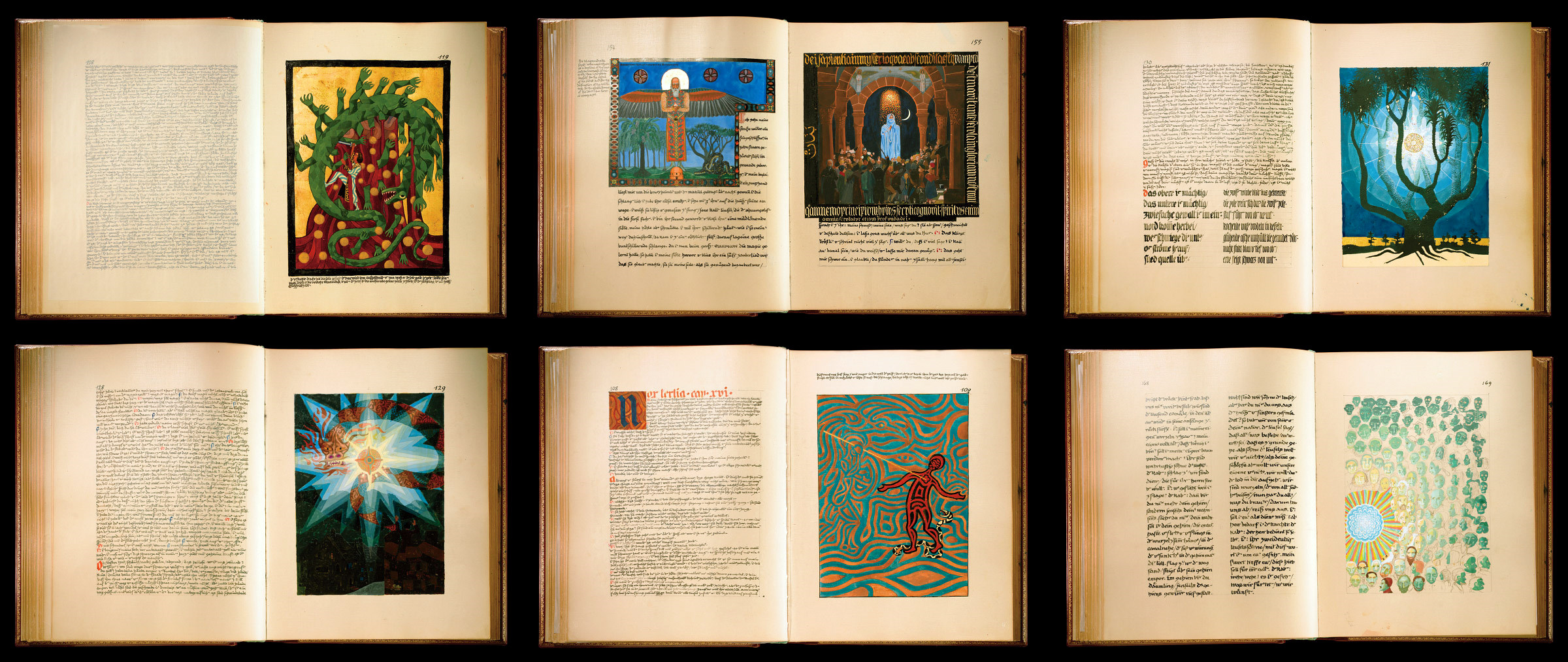

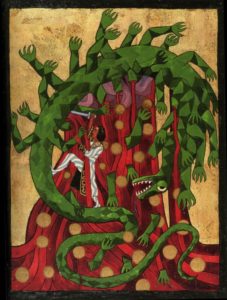

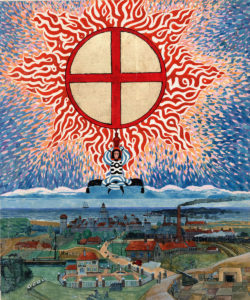

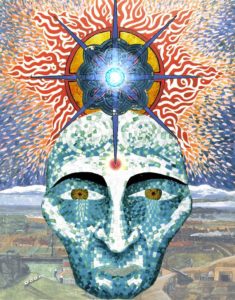

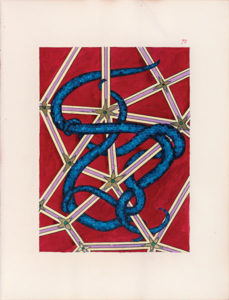

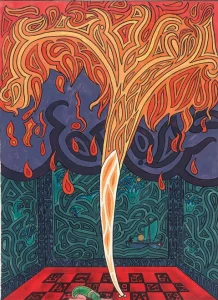

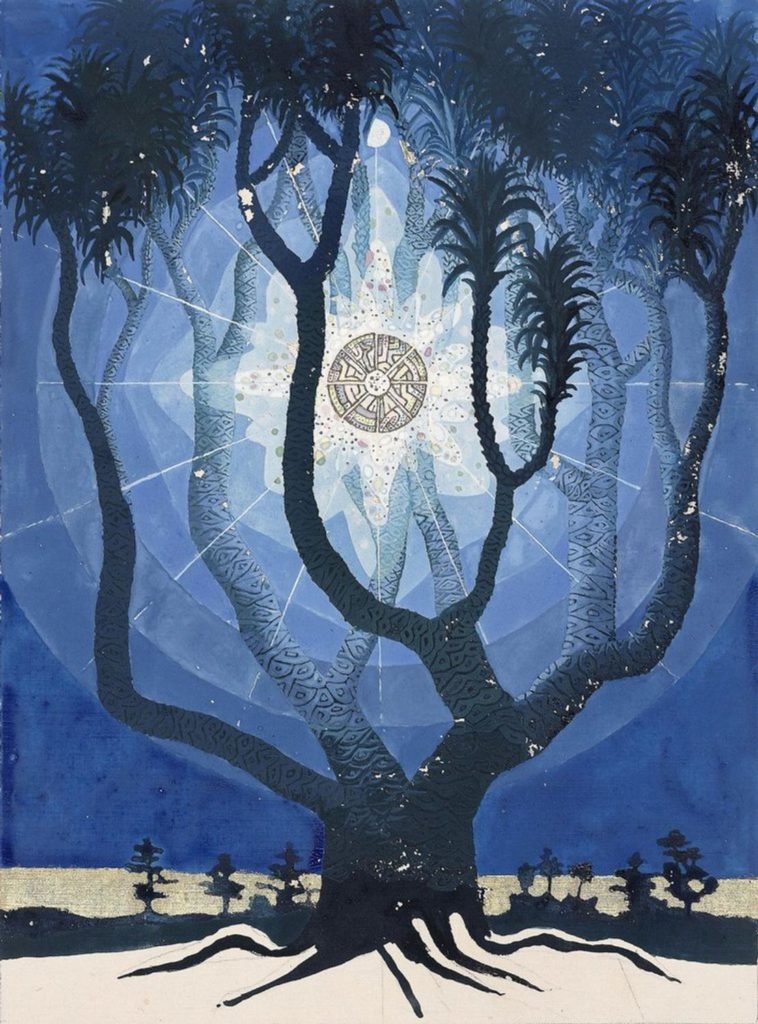

The psychotic is drowning while the artist is swimming. The waters both inhabit, however, are the same. Written in a similar voice to the King James Bible, The Red Book has a religious and transcendent quality. It is written on vellum in heavy calligraphy with gorgeous hand illuminated script. Jung took inspiration for mystical and alchemical texts for its full page illustrations.

It is easier to define The Red Book by what it is not than by what it is. According to Jung, it is not a work of art. It is not a scholarly psychological endeavor. It is also not an attempt to create a religion. It was an attempt for Jung to heal himself in a time of pain and save himself from madness by giving voice to the forces underneath his partial psychotic episode. The Red Book was a kind of container to help Jung witness the forces of the deep unconscious. In the same way, religion and Jungian psychology are containers for the ancient unconscious forces in the vast ocean under the human psyche.

Lament of the Dead, Psychology after Carl Jung’s The Red Book is a dialogue between ex Jungian analyst James Hillman and Jungian scholar Sonu Shamdasani about the implications the Red Book has for Jungian psychology. Like the Red Book it was controversial when it was released.

James Hillman was an early protege of Jung who later became a loud critic of parts of Jung’s psychology. Hillman wanted to create an “archetypal” psychology that would allow patients to directly experience and not merely analyze the psyche. His new psychology never really came together coherently and he never found the technique to validate his instinct. Hillman had been out of the Jungian fold for almost 30 years before he returned as a self appointed expert advisor during the publication of The Red Book. Hillman’s interest in The Red Book was enough to make him swallow his pride, and many previous statements, to join the Jungians once again. It is likely that the archetypal psychology he was trying to create is what The Red Book itself was describing.

Sonu Shamdasani is not a psychologist but a scholar of the history of psychology. His insights have the detachment of the theoretical where Hillman’s are more felt and more intuitive but also more personal. One gets the sense in the book that Hillman is marveling painfully at an experience that he had been hungry for for a long time. The Red Book seems to help him clarify the disorganized blueprints of his stillborn psychological model. While there is a pain in Hillman’s words there is also a peace that was rare to hear from such a flamboyant and unsettled psychologist.

Sonu Shamdasani is the perfect living dialogue partner for Hillman to have in the talks that make up Lament. Shamdasani has one of the best BS detectors of maybe any Jungian save David Tacey. Shamdasani has deftly avoided the fads, misappropriations and superficialization that have plagued the Jungian school for decades. As editor of the Red Book he knows more about the history and assembly of the text than any person save for Jung. Not only is he also one of the foremost living experts on Jung, but as a scholar he does not threaten the famously egotistical Hillman as a competing interpreting psychologist. The skin that Shamdasani has in this game is as an academic while Hillman gets to play the prophet and hero of the new psychology they describe without threat or competition.

Presumedly these talks were recorded as research for a collaborative book to be co authored by the two friends and the death of Hillman in 2011 made the publication as a dialogue in 2013 a necessity. If that is not the case the format of a dialogue makes little sense. If that is the case it gives the book itself an almost mystical quality and elevates the conversation more to the spirit of a philosophical dialogue.

We are only able to hear these men talk to each other and not to us. There is a deep reverberation between the resonant implications these men are seeing The Red Book have for modern psychology. However, they do not explain their insights to the reader and their understandings can only be glimpsed intuitively. Like the briefcase in the film Pulp Fiction the audience sees the object through its indirect effect on the characters. We see the foggy outlines of the ethics that these men hope will guide modern psychology but we are not quite able to see it as they see it. We have only an approximation through the context of their lives and their interpretation of Jung’s private diary. This enriches a text that is ultimately about the limitations of understanding.

One of the biggest criticisms of the book when it was published was that the terms the speaker used are never defined and thus the book’s thesis is never objectivised or clarified. While this is true if you are an English professor, the mystic and the therapist in me see these limitations as the book’s strengths. The philosophical dialectic turns the conversation into an extended metaphor that indirectly supports the themes of the text. The medium enriches the message. Much like a socratic dialogue or a film script the the authors act more as characters and archetypes than essayists. The prophet and the scholar describe their function and limitations as gatekeepers of the spiritual experience.

Reading the Lament, much like reading The Red Book, one gets the sense that one is witnessing a private but important moment in time. It is a moment that is not our moment and is only partially comprehensible to anyone but the author(s). Normally that would be a weakness but here it becomes a strength. Where normally the reader feels that a book is for them, here we feel that we are eavesdropping through a keyhole or from a phone line downstairs. The effect is superficially frustrating but also gives Lament a subtle quality to its spirituality that The Red Book lacks.

Many of the obvious elements for a discussion of the enormous Red Book are completely ignored in the dialogue. Hillman and Shamdasani’s main takeaway is that The Red Book is about “the dead”. What they mean by “the dead” is never explained directly. This was a major sticking point for other reviewers, but I think their point works better undefined. They talk about the dead as a numinous term. Perhaps they are speaking about the reality of death itself. Perhaps about the dead of history. Perhaps they are describing the impenetrable veil we can see others enter but never see past ourselves. Maybe the concept contains all of these elements. Hillman, who was 82 at the time of having the conversations in Lament, may have been using The Red Book and his dialogue with Shamdasani to come to terms with his feelings about his own impending death.

Perhaps it is undefined because these men are feeling something or intuitively, seeing something that the living lack the intellectual language for. It is not that the authors do not know what they are talking about. They know, but they are not able to completely say it. Hillman was such an infuriatingly intuitive person that his biggest downfall in his other books is that he often felt truths that he could not articulate. Instead he retreated into arguing the merits of his credentials and background or into intellectual archival of his opinions on philosophers and artists. In other works this led to a didactic and self righteous tone that his writing is largely worse for. In Lament Hillman is forced to talk off the cuff and that limitation puts him at his best as a thinker.

Perhaps it is undefined because these men are feeling something or intuitively, seeing something that the living lack the intellectual language for. It is not that the authors do not know what they are talking about. They know, but they are not able to completely say it. Hillman was such an infuriatingly intuitive person that his biggest downfall in his other books is that he often felt truths that he could not articulate. Instead he retreated into arguing the merits of his credentials and background or into intellectual archival of his opinions on philosophers and artists. In other works this led to a didactic and self righteous tone that his writing is largely worse for. In Lament Hillman is forced to talk off the cuff and that limitation puts him at his best as a thinker.

In his review of Lament, David Tacey has made the very good point that Jung abandoned the direction that The Red Book was taking him in. Jung saw it as a dead end for experiential psychology and retreated back into analytical inventorying of “archetypes”. On the publication of The Red Book, Jungians celebrate the book as the “culmination” of Jungian thought when instead it was merely a part of its origins. The Red Book represents a proto-Jungian psychology as Jung attempted to discover techniques for integration. Hillman and Shamdasani probe the psychology’s origins for hints of its future in Lament.

Hillman and Shamdasani’s thesis is partially a question about ethics and partially a question about cosmology. Are there any universal directions for living and behaving that Jungian psychology compels us towards (ethics)? Is there an external worldview that the, notoriously phenomenological, nature of Jungian psychology might imply (cosmology)? These are the major questions Hillman and Shamdasani confront in Lament.Their answer is not an answer as much as it is a question for the psychologists of the future.

Their conclusion is that “the dead” of our families, society, and human history foist their unlived life upon us. It is up to us, and our therapists, to help us deal with the burden of “the dead”. It is not us that live, but the dead that live through us. Hillman quotes W.H. Auden several times:

We are lived through powers that we pretend to understand.

– W.H. Auden

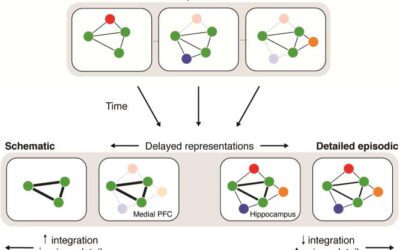

A major tenant of Jungian psychology is that adult children struggle under the unlived life of the parent. The Jungian analyst helps the patient acknowledge and integrate all of the forces of the psyche that the parent ran from, so they are not passed down to future generations. A passive implication of the ethics and the cosmology laid out in Lament, is that to have a future we must reckon with not only the unlived life of the parent but also the unlived life of all the dead.

It is our job as the living to answer the questions and face the contradictions our humanity posits in order to discover what we really are. The half truths and outright lies from the past masquerade as tradition for traditions sake, literalized religion, and unconscious tribal identity must be overthrown. The weight of the dead of history can remain immovable if we try to merely discard it but drowns us if we cling to it too tightly. We need to use our history and traditions to give us a container to reckon with the future. The container must remain flexible if we are to grow into our humanity as a society and an aware people.

If you find yourself saying “Yes, but what does “the dead” mean!” Then this book is not for you. If you find yourself confused but humbled by this thesis then perhaps it is. Instead of a further explanation of the ethical and cosmological future for psychology that his book posits I will give you a tangible example about how its message was liberatory for me.

explanation of the ethical and cosmological future for psychology that his book posits I will give you a tangible example about how its message was liberatory for me.

Hillman introduces the concepts of the book with his explanation of Jung’s reaction to the theologian and missionary Albert Schweitzer. Jung hated Schweitzer. He hated him because he had descended into Africa and “gone native”. In Jung’s mind Schweitzer had “refused the call” to do anything and “brought nothing home”. Surely the Africans that were fed and clothed felt they had been benefited! Was Jung’s ethics informed by racism, cluelessness, arrogance or some other unknown myopism?

A clue might be found in Jung’s reaction to modern art exploring the unconscious or in his relationship with Hinduism. Jung took the broad strokes of his psychology from the fundamentals of the brahman/atman and dharma/moksha dichotomies of Hinduism. Jung also despised the practice of eastern mysticism practices by westerners but admired it in Easterners. Why? His psychology stole something theoretical that his ethics disallowed in direct practice.

Jung’s views on contemporary (modern) artists of his time were similar. He did not want to look at depictions of the raw elements of the unconscious. In his mind discarding all the lessons of classicism was a “cop out”. He viewed artists that descended into the abstract with no path back or acknowledgement of the history that gave them that path as failures. He wanted artists to make the descent into the subjective world and return with a torch of it’s fire but not be consumed by it blaze. Depicting the direct experience of the unconscious was the mark of a failed artist to Jung. To Jung the destination was the point, not the journey. The only thing that mattered is what you were able to bring back from the world of the dead. He had managed to contain these things in The Red Book, why couldn’t they? The Red Book was Jung’s golden bough.

Jung took steps to keep the art in The Red Book both outside of the modernist tradition and beyond the historical tradition. The Red Book uses a partially medieval format but Jung both celebrates and overcomes the constraints of his chosen style. The Red Book was not modern or historical, it was Jung’s experience of both. In Lament, Hillman describes this as the ethics that should inform modern psychology. Life should become ones own but part of ones self ownership is that we take responsibility for driving a tradition forward not a slave to repeating it.

Oddly enough the idea of descent and return will already be familiar to many Americans through the work of Joseph Campbell. Campbell took the same ethics of descent and return to the unconscious as the model of his “monomyth” model of storytelling. This briefly influenced psychology and comparative religion in the US and had major impact on screenwriters to this day. Campbells ethics are the same as Jung’s. If one becomes stuck on the monomyth wheel, or the journey of the descent and return, one is no longer the protagonist and becomes an antagonist. Campbell, and American post jungians in general were not alway great attributing influences and credit where it was due.

Oddly enough the idea of descent and return will already be familiar to many Americans through the work of Joseph Campbell. Campbell took the same ethics of descent and return to the unconscious as the model of his “monomyth” model of storytelling. This briefly influenced psychology and comparative religion in the US and had major impact on screenwriters to this day. Campbells ethics are the same as Jung’s. If one becomes stuck on the monomyth wheel, or the journey of the descent and return, one is no longer the protagonist and becomes an antagonist. Campbell, and American post jungians in general were not alway great attributing influences and credit where it was due.

Jung was suspicious of the new age theosophists and psychadelic psychonauts that became enamored with the structure of the unconscious for the unconscious sake. Where Lament shines is when Hillman explains the ethics behind Jung’s thinking. Jung lightly implied this ethics but was, as Hillman points out, probably not entirely conscious of it. One of Lament’s biggest strengths and weaknesses is that it sees through the misappropriations of Jungian psychology over the last hundred years. Both of the dialogue’s figures know the man of Jung so well that they do not need to address how he was misperceived by the public. They also know the limitations of the knowable.

This is another lesson that is discussed in Lament. Can modern psychology know what it can’t know? That is my biggest complaint with the profession as it currently exists. Modern psychology seems content to retreat into research and objectivism. The medical, corporate, credentialist and academic restructuring of psychology in the nineteen eighties certainly furthered that problem. Jung did not believe that the descent into the unconscious without any hope of return was a path forward for psychology. This is why he abandoned the path The Red Book led him down. Can psychology let go of the objective and the researchable enough to embrace the limits of the knowable? Can we come to terms with limitations enough to heal an ego inflated world that sees no limits to growth?

I don’t know but I sincerely hope so.

I said that I would provide a tangible example of the application of this book in it’s review, so here it is:

I have always been enamored with James Hillman. He was by all accounts a brilliant analyst. He also was an incredibly intelligent person. That intellect did not save him. Hillman ended his career as a crank and a failure in my mind. In this book you see Hillman contemplate that failure. You also see Hillman attempt to redeem himself as he glimpses the unglimpseable. He sees something in the Red Book that he allows to clarify his earlier attempt to revision psychology.

Hillman’s attempt to reinvent Jungian psychology as archetypal psychology was wildly derided. Largely, because it never found any language or technique for application and practice. Hillman himself admitted that he did not know how to practice archetypal psychology. It’s easy to laugh at somebody who claims to have reinvented psychology and can’t even tell you what you do with their revolutionary invention.

However, I will admit that I think Hillman was right. He knew that he was but he didnt know how he was right. It is a mark of arrogance to see yourself as correct without evidence. Hillman was often arrogant but I think here he was not. Many Jungian analysts would leave the Jungian institutes through the 70, 80s and 90s to start somatic and experiential psychology that used Jung as a map but the connection between the body and the brain as a technique. These models made room for a direct experience in psychology that Jungian analysis does not often do. It added an element that Jung himself had practiced in the writing of The Red Book. Hillman never found this technique but he was correct about the path he saw forward for psychology. He knew what was missing.

I started Taproot Therapy Collective because I felt a calling to dig up the Jungian techniques of my parent’s generation and reify them. I saw those as the most viable map towards the future of psychology, even though American psychology had largely forgotten them. I also saw them devoid of a practical technique or application for a world where years of analysis cost more than most trauma patients will make in a lifetime. I feel that experiential and brain based medicine techniques like brainspotting, ETT, and parts based therapy are the future of the profession.

I started Taproot Therapy Collective because I felt a calling to dig up the Jungian techniques of my parent’s generation and reify them. I saw those as the most viable map towards the future of psychology, even though American psychology had largely forgotten them. I also saw them devoid of a practical technique or application for a world where years of analysis cost more than most trauma patients will make in a lifetime. I feel that experiential and brain based medicine techniques like brainspotting, ETT, and parts based therapy are the future of the profession.

Pathways like brainspotting, sensorimotor therapy, somatic experiencing, neurostimulation, ketamine, psilocybin or any technique that allows the direct experience of the subcortical brain is the path forward to treat trauma. These things will be at odds with the medicalized, corporate, and credentialized nature of healthcare. I knew that this would be a poorly understood path that few people, even the well intentioned, could see. I would never have found it if I had refused the call of “the dead”.

Lament is relevant because none of those realizations is somewhere that I ever would have gotten without the tradition that I am standing on top of. I am as, Isaac Newton said, standing on the shoulders of giants. Except Isaac Newton didn’t invent that phrase. It was associated with him but he was standing on the tradition of the dead to utter a phrase first recorded in the medieval period. The author of its origin is unknown because they are, well, dead. They have no one to give their eulogy.

The ethics and the cosmology of Lament, is that our lives are meant to be a eulogy for our dead. Lament, makes every honest eulogy in history become an ethics and by extension a cosmology. Read Pericles eulogy from the Peloponesian war in Thucydides. How much of these lessons are still unlearned? I would feel disingenuous in my career unless I tell you who those giants are that I stand on. They are David Tacey, John Beebe, Sonu Shamdasani, Carl Jung, Fritz Perls, Karen Horney, and Hal Stone. Many others also.

I would never have heard the voice of James Hillman inside myself unless I had learned to listen to the dead from his voice beyond the grave. It would have been easy for me to merely critize his failures instead of seeing them as incomplete truths. Hillman died with many things incomplete, as we all inevitably will. Lament helped me clarify the voices that I was hearing in the profession. Lament of the Dead is a fascinating read not because it tells us exactly what to do with the dead, or even what they are. Lament is fascinating because it helps us to see a mindful path forward between innovation and tradition.

The contents of the collective unconscious cannot be contained by one individual. Just as Jungian psychology is meant to be a container to help an individual integrate the forces of the collective unconscious, attention to the unlived life of the historical dead can be a kind of container for culture. Similarly to Jungian psychology the container is not meant to be literalized or turned into a prison. It is a lens and a buffer to protect us until we are ready and allow us to see ourselves more clearly once we are. Our project is to go further in the journey of knowing ourselves where our ancestors failed to. Our mindful life is the product of the unlived life of the dead it is our life that is their lament.

I will end with a few quotes from the often paradoxical Hillman.

Soul…is the “patient” part of us. Soul is vulnerable and suffers; it is passive and remembers. It is water to the spirit’s fire, like a mermaid who beckons the heroic spirit into the depths of passions to extinguish its certainty. Soul is imagination, a cavernous treasury…Whereas spirit chooses the better part and seeks to make all one. Look up, says spirit, gain distance; there is something beyond and above, and what is above is always, and always superior.

…from the perspective of spirit..the soul must be disciplined, its desires harnessed, imagination emptied, dreams forgotten, involvements dried. For soul, says spirit, cannot know, neither truth, nor law, nor cause. … So there must be spiritual disciplines for the soul, ways in which soul shall conform with models enunciated for it by spirit.

…But from the viewpoint of the psyche…movement upward looks like repression. There may well be more psychopathology actually going on while transcending than while being immersed in pathologizing. For any attempt at self-realization without full recognition of the psychopathology that resides, as Hegel said, inherently in the soul is in itself pathological, an exercise in self-deception.

…spirit is after ultimates and it reveals by means of a via negativa. “Neti, neti,” it says, “not this, not that.” Strait is the gate and only first or last things will do. Soul replies by saying, “Yes, this too has place, may find its archetypal significance, belongs in a myth.” The cooking vessel of the soul takes in everything, everything can become soul; and by taking into its imagination any and all events, psychic space grows.

A Blue Fire: Selected Writings by James Hillman, p. 123

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Bibliography:

Abram, J. (2013). The Language of Winnicott: A Dictionary of Winnicott’s Use of Words. Karnac Books.

Addington, J. (2017). Mourning, Melancholia, and Madness: Psychoanalytic Perspectives. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 37(4), 237-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2017.1299484

Bachelard, G. (1994). The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Bernstein, J. W. (2005). The Analytical Psychology of James Hillman. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45(3), 392-423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167805277108

Bosnak, R. (2007). Embodiment: Creative Imagination in Medicine, Art and Travel. Routledge.

Brown, N. W. (1959). Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History. Wesleyan University Press.

Cambray, J., & Carter, L. (Eds.). (2004). Analytical Psychology: Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analysis. Brunner-Routledge.

Casement, A. (2001). Carl Gustav Jung. SAGE.

Dallett, J. O. (1982). James Hillman’s Archetypal Psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist, 10(3), 229-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.1982.9976858

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. Basic Books.

Guggenbühl-Craig, A. (1999). Power in the Helping Professions. Spring Publications.

Hauke, C. (2000). Jung and the Postmodern: The Interpretation of Realities. Routledge.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1996). The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. Random House.

Hillman, J. (1998). The Thought of the Heart and the Soul of the World. Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (2013). A Blue Fire: Selected Writings by James Hillman. Routledge.

Hogenson, G. B. (2001). The Baldwin Effect: A Neglected Influence on C.G. Jung’s Evolutionary Thinking. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 46(4), 591-611. https://doi.org/10.1111/1465-5922.00265

Hollis, J. (1993). The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife. Chiron Publications.

Jacobi, J. (1973). The Psychology of C.G. Jung. Yale University Press.

Jaffe, A. (1979). C.G. Jung: Word and Image. Princeton University Press.

Kugler, P. J. (1982). The Alchemy of Discourse: An Archetypal Approach to Language. Associated University Presses.

Kast, V. (1992). Joy, Inspiration, and Hope. Fromm International.

Laing, R. D. (1990). The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise. Penguin.

Libbrecht, K. (1995). Beyond the Rational Mind: The Central Role of Imagination in Human Existence. Lindisfarne Press.

Lillard, A. S. (2007). Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius. Oxford University Press.

Mathews, F. (1991). The Ecological Self. Routledge.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the Soul: A Guide for Cultivating Depth and Sacredness in Everyday Life. HarperCollins.

Moreno, A. (1995). Jung, Gods, and Modern Man. University of Notre Dame Press.

Pietikäinen, P. (1998). Archetypes as Symbolic Forms. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 43(3), 325-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/1465-5922.00019

Romanyshyn, R. D. (1982). Psychological Life: From Science to Metaphor. University of Texas Press.

Samuels, A. (1993). The Political Psyche. Routledge.

Shamdasani, S. (2003). Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge University Press.

Shamdasani, S. (2012). C.G. Jung: A Biography in Books. W.W. Norton & Company.

Slattery, D. P. (2000). The Wounded Body: Remembering the Markings of Flesh. State University of New York Press.

Stevens, A. (1994). Jung: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Tacey, D. J. (2001). Jung and the New Age. Brunner-Routledge.

von Franz, M. L. (1974). Number and Time: Reflections Leading Toward a Unification of Depth Psychology and Physics. Northwestern University Press.

Whitmont, E. C. (1969). The Symbolic Quest: Basic Concepts of Analytical Psychology. Princeton University Press.

Woodman, M. (1982). Addiction to Perfection: The Still Unravished Bride. Inner City Books.

Further Reading:

Bair, D. (2003). Jung: A Biography. Little, Brown and Company.

Beebe, J. (2005). Foreword. In J. Hillman, Senex and Puer (pp. xi-xv). Spring Publications.

Chodorow, J. (1997). Jung on Active Imagination. Princeton University Press.

Corbett, L. (2011). The Religious Function of the Psyche. Routledge.

Hadfield, J. A. (1950). Dreams and Nightmares. Pelican.

Huskinson, L. (Ed.). (2014). Eavesdropping: The Psychotherapist in Film and Television. Routledge.

Hillman, J. (1964). Suicide and the Soul. Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1982). Anima Mundi: The Return of the Soul to the World. Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1989). A Blue Fire. Harper Perennial.

Jacobi, J. (1942). The Psychology of C.G. Jung. Yale University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche (2nd ed.). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Kalsched, D. (1996). The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. Routledge.

Moore, T. (1994). Soul Mates: Honoring the Mysteries of Love and Relationship. HarperOne.

Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge.

Tacey, D. J. (2013). Edge of the Sacred: Jung, Psyche, Earth. Springer.

0 Comments