Of course, the great irony of the countercultural design revolution is how quickly it was co-opted by the very consumerist system it claimed to reject. By the mid-70s, the trappings of hippie style had been thoroughly commodified, churned out in mass-produced form by the big retail brands. The anti-materialist values of the counterculture proved remarkably easy to repackage as a materialist lifestyle, one that could be bought into with the right throws pillows and wall art.

This tension between rebellion and cooptation would come to define the design landscape of the late 20th century. Even as subcultures continued to arise with their own transgressive visual languages, the mechanisms of consumer capitalism found ever more sophisticated ways to absorb and neutralize them. The distance between the authentic and the mass-produced, the cool and the sellout, grew harder and harder to define.

Postmodernism & the Digital Age

The 1980s marked the beginning of a new cultural paradigm, one defined by a skepticism towards grand narratives and a playful embrace of surface over substance. Postmodernist thinkers challenged the very notion of a singular, universal Truth, arguing that meaning was always contingent on cultural context. In the realm of design, this translated into an eclectic, irreverent attitude that freely mixed historical references, pop culture cliches and ironic self-awareness.

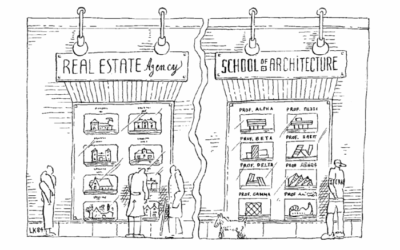

Architects like Robert Venturi and Michael Graves pioneered a new approach that rejected the austerity of modernist glass boxes in favor of witty, decorative facades that nodded to classical and vernacular traditions. Philip Johnson’s AT&T building, with its Chippendale-inspired broken pediment, became an icon of the style. Interiors grew more theatrical and scenographic, filled with knowingly kitschy historical reproductions and audaciously patterned fabrics.

The explosion of digital technology in the 1990s added a new futuristic overlay to the postmodernist mélange. Translucent iMacs in candy colors and proto-smartphones with alien form factors captured the techy optimism of the early internet age. Pixelated graphics and glitchy, low-res aesthetics infiltrated fashion and branding, telegraphing a fascination with the strange new textures of cyberspace.

At the same time, a strain of techno-utopianism emerged that sought to revive the heroic purity of mid-century modernism for the digital age. Sleek, monochromatic gadgets with seamless user interfaces reflected a fantasy of friction-free global connectivity. Open plan office spaces filled with Frank Gehry chairs and Jeff Koons balloon animals projected an air of disruptive innovation and frictionless collaboration.

Psychologically, the postmodern era reflects a culture grappling with the fragmenting effects of an incipient information revolution. In a world where global communication networks were beginning to erode traditional notions of time, space, and identity, design became a way to navigate the disorientation. By sampling freely from history and remixing it with the frenetic pace of digital life, postmodern style enacted the vertiginous experience of a society in flux.

The ironic detachment and self-referentiality of the period can also be seen as a coping mechanism for a generation raised on media saturation and advertising overload. Having grown up with the relentless commodification of the counterculture, savvy consumers had become adept at decoding the hidden social programming behind designed objects. Postmodern style allowed them to signal their sophistication by consuming with a wink, participating in consumer culture while seeming to hover above it.

Contemporary Currents

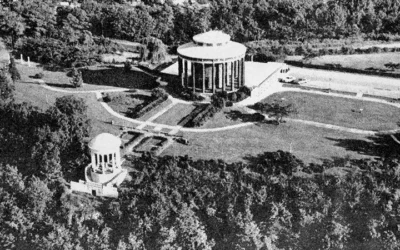

reclaimed industrial space

dematerialized digital design

In the first decades of the 21st century, the pace of technological and cultural change has only accelerated, leading to a design landscape that feels increasingly fractured and difficult to define. The sheer volume and velocity of visual information circulating across global digital networks has collapsed the cycle of trends and movements to a matter of weeks or even days. Microtrends arise and evaporate with bewildering speed, as social media platforms enable niche aesthetics to find viral popularity overnight.

One overarching development has been the increasing “dematerialization” of design in the digital age. As more and more of life is mediated through screens, physical objects have lost some of their primacy as carriers of cultural meaning. Ephemeral, experiential modes of design like UX, UI, social media aesthetics and emoji usage have become key arenas where cultural values and identities are negotiated.

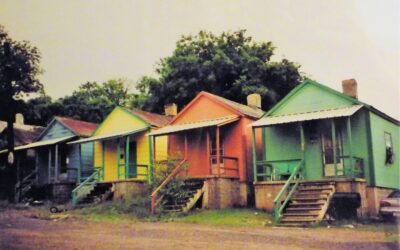

This is not to say that physical design has become irrelevant. If anything, the bodily experience of materiality has taken on a new aura of authenticity and luxury in an increasingly virtual world. “Artisanal” and “bespoke” have become buzzwords, as consumers seek out handcrafted, one-of-a-kind objects as an antidote to digital flatness. Rough-hewn, organic materials like live-edge wood and hand-thrown ceramics tap into a desire for tactility and rootedness.

At the same time, concern over climate change and resource scarcity has given rise to a new wave of ecological design thinking. Architects and product designers are increasingly focused on creating objects and environments that are sustainable, biodegradable, and harmoniously integrated with natural systems. Biomimicry, modular construction, and closed-loop manufacturing reflect an ethos of “cradle-to-cradle” design that rejects the linear model of extraction and waste.

On a psychological level, the diversity and speed of contemporary design trends reflects a culture grappling with a crisis of meaning in the face of dizzying change. In a world where identities are fluid, information is suspect, and the future feels precarious, design has become a way to ground oneself in a fleeting present. For some, this means embracing the hyper-ephemeral, meme-driven churn of digital style as a kind of absurdist play. For others, it means seeking out objects and experiences that feel timelessly authentic, rooted in primal sensory pleasures and age-old crafts.

In this context, the role of the designer has become at once more challenging and more vital than ever. In a sea of endless and often cynical commercial messaging, there is a hunger for design that feels genuinely meaningful and humane. This requires a deep understanding of the emotional and cultural resonances that objects can carry, as well as a commitment to creating things that enrich rather than exploit our common life.

As we look to the future, it’s clear that the pace of change will only continue to accelerate. Technologies like AI, VR/AR, and the internet of things promise to further blur the line between the digital and physical, the real and the virtual. In the face of such upheaval, the role of designers will be to find ways to anchor us in our embodied humanity, to craft objects and experiences that stimulate our senses, tell meaningful stories, and connect us to one another and the living planet we share. In an age of distraction and dislocation, good design may be our best hope for finding beauty, meaning and belonging in the here and now.

What’s the Future of the Psychology of Design?

Looking back over three centuries of American design, we see a culture in constant tension between the allure of progress and a longing to anchor itself in bedrock values. From the democratic restraint of 18th century Federal style to the earthy vibes of 1970s macramé, each era’s aesthetic proclivities reflect the deeper psychological currents of the age.

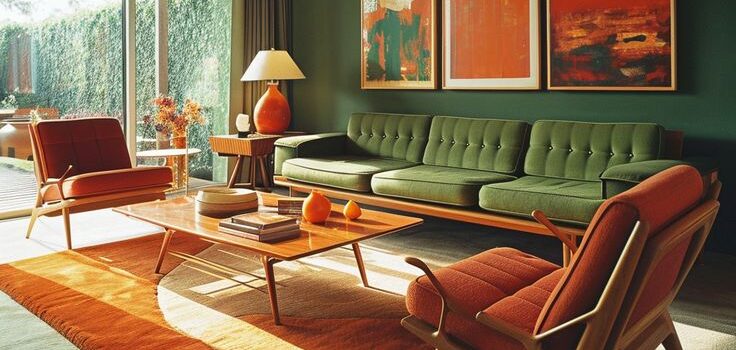

Consistently, moments of dizzying technological and social upheaval have given rise to design movements that seek to return to a sense of authenticity and rootedness. Whether in the form of the handcrafted simplicity of the Arts & Crafts era or the rustic materials and natural shapes of 1970s environmental design, aesthetic responses to modernity have often hinged on a rejection of cheap, mass-produced superficiality in favor of sensual and spiritual anchors.

At the same time, American design has consistently reflected a restless fascination with novelty, an almost utopian faith in the power of human ingenuity to reshape the world. From the gee-whiz machine forms of 1930s streamline moderne to the candy-colored translucence of 1990s iMac futurism, each generation has found ways to aestheticize its era’s most exciting new materials, technologies and lifestyles.

This creative tension, between the timeless and the cutting-edge, the organic and the manufactured, the rustic and the sophisticated, is in many ways the defining dialectic of American culture. It speaks to a national psyche caught between a reverence for the frontier spirit and a yearning for cosmopolitan refinement, a rugged individualism and a hunger for communal belonging.

As we move deeper into the 21st century, these tensions show no sign of resolving. If anything, the pace of technological change and social upheaval seems poised to accelerate, challenging designers to find ever more thoughtful and emotionally relevant ways to shape the material world. The objects we surround ourselves with will continue to reflect our deepest hopes and fears, our kneejerk responses and considered values, our nostalgic longings and boldest visions of the future.

In this endless balancing act between the past, present and future, one thing remains constant: the vital role of beauty and craft in anchoring us to our humanity. In an age of virtual abstraction and consumerist churn, the work of designers will be to create objects and environments that stimulate our senses, tell nourishing stories, and facilitate genuine human connection. Armed with a sensitive understanding of history, culture and psychology, the designers of tomorrow can help lead us towards a material world that feels richer, truer and more meaningful than ever.

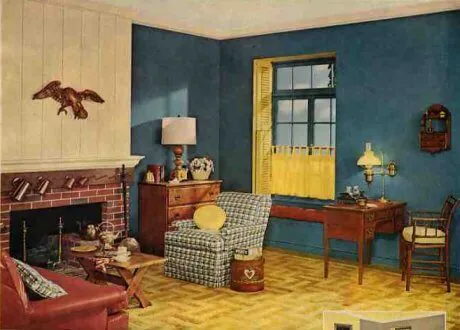

The years following the Revolutionary War saw the newly independent United States begin to more confidently assert its own national aesthetic, even as it continued to take cues from Europe. Neoclassicism, which hearkened back to the clean lines and rational proportions of ancient Greece and Rome, was the dominant style of the late 1700s on both sides of the Atlantic. In the US, this expressed itself in what we now call the Federal style.

The years following the Revolutionary War saw the newly independent United States begin to more confidently assert its own national aesthetic, even as it continued to take cues from Europe. Neoclassicism, which hearkened back to the clean lines and rational proportions of ancient Greece and Rome, was the dominant style of the late 1700s on both sides of the Atlantic. In the US, this expressed itself in what we now call the Federal style. The first half of the 19th century saw a wild proliferation of revival styles in

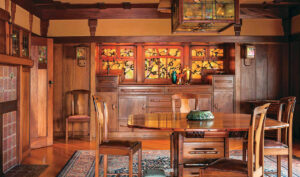

The first half of the 19th century saw a wild proliferation of revival styles in  dAs the 19th century drew to a close, a backlash emerged against both the eclectic chaos of Victorian style and the shoddy uniformity of mass production. The

dAs the 19th century drew to a close, a backlash emerged against both the eclectic chaos of Victorian style and the shoddy uniformity of mass production. The

0 Comments