Should Psychotherapy Ponder the Mysteries of Philosophy and Anthropology?

The specialized and fragmented nature of modern psychology has led to an abstracted and decontextualized view of the self, one that is disconnected from the embodied, embedded, and enactive dimensions of human experience. By drawing upon the insights of anthropology, philosophy, and the study of ancient religious traditions, we can begin to re-imagine psychology as a more holistic and integrative discipline, one that recognizes the deep intertwining of mind, body, culture, and environment in shaping human experience and well-being.

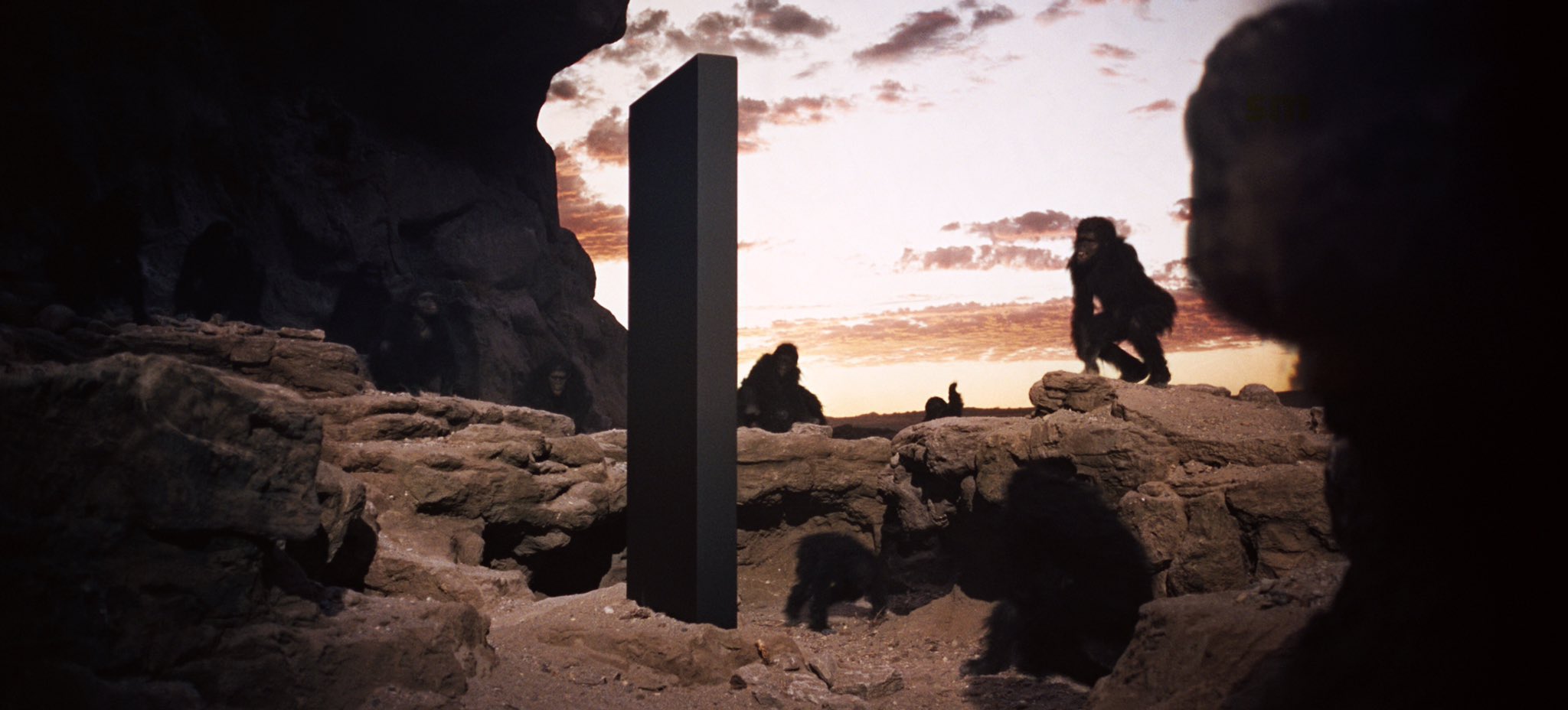

The human mind is a paradox, shaped by layers of cognition and consciousness that defy simplistic, reductionistic explanations. As fields like anthropology and evolutionary biology reveal, our ways of thinking and being in the world are profoundly influenced by embodied, symbolic, and even religious modes of understanding that have been integral to human experience since the dawn of our species.

Yet modern psychotherapy, in its quest for scientific legitimacy and its embrace of medicalized models of the mind, has often ignored or marginalized these crucial dimensions of the self. Dominated by approaches that prioritize logical, language-based interventions and symptom-focused treatments, the field has become disconnected from the rich tapestry of human cognition and the transformative power of ritual, symbolism, and somatic experience.

As a result, psychotherapy faces a crisis of both understanding and effectiveness, particularly when it comes to addressing the complex, multi-layered nature of trauma and the paradoxical workings of the human psyche. To truly heal and transform, therapy must find ways to engage with the full spectrum of consciousness, bridging the gaps between reason and emotion, mind and body, the individual and the collective.

Fortunately, a new generation of therapeutic models is emerging that offer hope for this kind of integrative, holistic approach. Modalities like EMDR, brainspotting, emotional transformation therapy, lifespan integration, somatic experiencing, and parts-based therapy are grounded in a recognition of the embodied, symbolic, and multifaceted nature of the self. By working with the brain’s multiple systems and the body’s innate wisdom, these approaches can access and transform layers of experience that language alone cannot reach.

However, the path forward is not without obstacles. The current incentive structures and priorities of the mental health field often discourage the kind of interdisciplinary exploration and innovation needed to develop and refine these integrative models. Researchers and practitioners who seek to bridge the worlds of psychotherapy, anthropology, evolutionary studies, and comparative spirituality may find themselves marginalized or unsupported.

In this paper, we will argue that overcoming these obstacles is not only possible, but necessary for the future of effective, truly transformative psychotherapy. By examining the insights of anthropology and evolutionary biology, the wisdom of ancient and indigenous traditions, and the promise of emerging therapeutic models, we will make the case for a new vision of psychotherapy – one that honors the paradoxical, multi-layered nature of the self and the inevitability of embodied, symbolic, and even religious modes of healing. Only by embracing these ways of knowing and being can we hope to address the depths of human suffering and potential.

The Development of the Brain over Time and Competing Networks

The human brain has undergone a remarkable journey of evolution and development over the course of our species’ history. This process has not only shaped our cognitive abilities and social behaviors but also laid the foundation for the emergence of religious thought and practice. Central to this development is the precuneus, a region of the brain that has played a crucial role in the emergence of symbolic thought, meaning-making, and the capacity for religious experience.

The precuneus, located in the posterior part of the medial parietal lobe, serves as a hub of connectivity within the brain, linking various functional networks that were previously separate (Smith et al., 2015). This integration has allowed for the emergence of higher-order cognitive functions, such as self-awareness, theory of mind, and the ability to engage in abstract and symbolic thinking (Cavanna & Trimble, 2006).

As the precuneus expanded and developed throughout the course of human evolution, it enabled our ancestors to move beyond mere information processing and engage in the perception and interpretation of their experiences in a way that assigned meaning and significance to their lives (Rappaport, 2020). This capacity for meaning-making and symbolic thought laid the foundation for the emergence of religious and spiritual beliefs, as humans sought to understand their place in the world and their relationship to the forces that shaped their existence.

The development of the precuneus and other brain regions also gave rise to competing cognitive functions and networks, which may have created paradoxes and tensions that required religion as a solution. For example, the increased capacity for self-awareness and introspection, enabled by the precuneus, may have led to a heightened sense of individuality and separateness from the natural world. At the same time, the development of social cognition and theory of mind may have emphasized the importance of social bonds and the need for cooperation and shared beliefs (Dunbar, 2008).

These competing drives – towards individuation and social cohesion – may have created a paradox that was resolved through the emergence of religious beliefs and practices. By providing a shared framework of meaning and a sense of connection to something greater than oneself, religion may have served to bridge the gap between the individual and the collective, and to provide a sense of purpose and belonging in an increasingly complex and uncertain world (Boyer, 2001).

The theory of the bicameral mind, proposed by Julian Jaynes (1976), offers another perspective on the role of brain development in the emergence of religious thought. According to Jaynes, the early human mind was characterized by a split between the two hemispheres, with the right hemisphere generating auditory hallucinations that were interpreted as the voices of gods or ancestors. These voices provided guidance and direction, and served as a form of external authority in the absence of a fully developed sense of self and consciousness.

As language and symbolic thought developed, Jaynes argued, the bicameral mind began to break down, leading to the emergence of self-awareness and inner dialogue. This shift may have coincided with the emergence of more complex religious beliefs and practices, as humans sought to make sense of their newfound interiority and to find new sources of guidance and meaning.

While Jaynes’s theory remains factually incorrect, it might be metaphorically true. His Theory highlights the potential role of subjective thought and inner speech in the development of religious thought. The idea that early humans may have experienced a more fluid and permeable boundary between the self and the divine is true even if Jaynes biology timeline is not the cause.

The evolutionary theory of religion, as proposed by James George Frazer (1922), suggests that human religious thought progressed through three stages: magic, religion, and science. According to this view, early humans first relied on magical practices to control their environment, then transitioned to religious beliefs as they recognized the limitations of magic, and finally arrived at scientific thinking as the ultimate means of understanding and manipulating the world.

While this evolutionary framework has been criticized for its oversimplification and ethnocentrism, it highlights the ways in which religious thought may have emerged as a response to the challenges and uncertainties of human existence. As the human brain developed and became more complex, religion may have provided a means of coping with the existential anxiety and sense of vulnerability that came with increased self-awareness and the recognition of mortality (Becker, 1997).

Another perspective on the emergence of religion is the spandrel theory, which suggests that religious beliefs and practices may have arisen as a byproduct of other cognitive and social adaptations, rather than as a direct result of natural selection (Gould & Lewontin, 1979). According to this view, the capacity for religious thought may have emerged as a “spandrel” – a term borrowed from architecture to describe a feature that arises as a necessary consequence of other design elements, but which may then be co-opted for other functions.

For example, the development of language and symbolic thought, which were likely selected for their benefits in communication and social coordination, may have also given rise to the capacity for metaphorical and abstract thinking, which in turn laid the foundation for religious beliefs and practices. Similarly, the development of social cognition and the ability to attribute mental states to others (theory of mind) may have facilitated the emergence of beliefs in supernatural agents and the attribution of intentionality to natural phenomena (Boyer, 2001).

The development of the human brain, and particularly the emergence of the precuneus and its role in integrating various cognitive functions, has played a crucial role in the origins and evolution of religious thought and practice. By enabling the capacity for symbolic thought, meaning-making, and self-awareness, the precuneus laid the foundation for the emergence of religious beliefs and practices as a means of coping with the challenges and uncertainties of human existence.

At the same time, the competing cognitive functions and networks that emerged as a result of brain development may have created paradoxes and tensions that required religion as a solution. The theories of the bicameral mind, the evolutionary stages of religion, and the spandrel theory offer additional perspectives on the ways in which religious thought may have emerged as a byproduct or consequence of other cognitive and social adaptations.

As we continue to explore the origins and functions of religion from an evolutionary and cognitive perspective, it is important to recognize the complexity and diversity of religious experiences across cultures and throughout history. While the development of the brain may have laid the foundation for the emergence of religious thought, the specific forms and expressions of religious belief and practice are shaped by a wide range of cultural, social, and environmental factors. By integrating insights from evolutionary psychology, anthropology, and the cognitive sciences, we can develop a richer and more nuanced understanding of the enduring significance of religion for the human mind and society.

The History of Religion in Human and Pre-Human Species

The history of religion is a vast and complex tapestry, woven from the countless threads of human belief, practice, and experience across the ages. From the earliest evidence of spiritual awareness in prehistoric times to the diverse and multifaceted religious landscape of the present day, the story of religion is one of continuity and change, innovation and tradition, conflict and cooperation.

The earliest evidence of religious thought and practice dates back to the Paleolithic era, some 300,000 years ago. Archaeological findings from this period, such as the use of ochre in burials and the creation of figurines and cave art, suggest that early humans had a sense of spiritual awareness and engaged in ritualistic behaviors (Rossano, 2010). These practices likely involved animistic beliefs, shamanic traditions, and the veneration of ancestors and nature spirits.

One of the most famous examples of Paleolithic art is the Venus of Willendorf, a small statuette dating back to around 30,000 BCE. This figurine, with its exaggerated feminine features, has been interpreted as a representation of a mother goddess or fertility deity, reflecting the importance of reproduction and the cycle of life in early human societies (Soffer et al., 2000).

As human societies became more complex and organized during the Neolithic era, religious beliefs and practices also evolved. The development of agriculture and the emergence of settled communities led to the construction of megalithic monuments and sacred sites, such as Göbekli Tepe in Turkey and Stonehenge in England. These structures likely served as centers of religious and social activity, where people gathered to perform rituals, honor deities, and mark important events (Schmidt, 2010).

The Neolithic period also saw the emergence of more complex religious systems, such as the worship of deities associated with fertility, agriculture, and the natural world. The concept of a “Great Goddess” or “Earth Mother” appears to have been widespread during this time, reflecting the importance of the feminine principle and the cycles of birth, death, and regeneration (Gimbutas, 1989).

As civilizations developed in different parts of the world, religious beliefs and practices became more diverse and sophisticated. In ancient Mesopotamia, for example, the Sumerian and Babylonian cultures developed complex pantheons of gods and goddesses, each associated with specific aspects of nature and human life. The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the earliest known works of literature, reflects the religious and mythological beliefs of these cultures, including the search for immortality and the relationship between humans and the divine (George, 1999).

In ancient Egypt, religion was closely intertwined with the power and authority of the pharaohs, who were believed to be living gods. The Egyptian pantheon included a wide range of deities, such as Ra, the sun god, Osiris, the god of the underworld, and Isis, the goddess of magic and motherhood. The construction of the pyramids and other monumental tombs reflects the central role of religion in Egyptian society, as well as the belief in an afterlife and the importance of preserving the body for the journey to the underworld (Ikram, 2010).

The Axial Age, which lasted from approximately 800 BCE to 200 CE, was a pivotal period in the history of religion. This era saw the emergence of new religious and philosophical traditions in different parts of the world, including Hinduism and Buddhism in India, Confucianism and Taoism in China, Zoroastrianism in Persia, and monotheistic Judaism in Israel (Jaspers, 1953).

These traditions represented a significant shift in religious thought, moving away from the worship of multiple gods and goddesses towards a more abstract and universal concept of the divine. The Axial Age also saw the development of new forms of religious practice, such as monasticism, asceticism, and the pursuit of individual enlightenment.

The rise of Christianity and Islam in the centuries following the Axial Age marked another major turning point in the history of religion. These monotheistic faiths, which share common roots in the Abrahamic tradition, spread rapidly throughout the world, often through conquest and missionary activity. The establishment of the Christian church and the Islamic caliphate led to the development of new forms of religious authority and social organization, as well as the emergence of religious conflicts and persecutions.

The medieval period saw the consolidation of these religious traditions, as well as the emergence of new forms of spirituality and mysticism. The Crusades, which began in the 11th century, reflect the complex interplay of religious, political, and economic factors that shaped the medieval world. The development of scholasticism and the rise of the universities also contributed to the intellectual and cultural flourishing of this period, as scholars sought to reconcile faith and reason and to explore the mysteries of the divine.

The Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation marked a significant shift in the history of religion, as the authority of the Catholic Church was challenged and new forms of religious expression emerged. The development of humanism and the rediscovery of classical learning led to a renewed interest in individual spirituality and the pursuit of knowledge, while the ideas of reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin emphasized the importance of personal faith and the authority of scripture.

The Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries posed new challenges to traditional religious beliefs and practices. The development of rational and empirical methods of inquiry led to a questioning of religious dogma and a growing interest in the natural world and the place of religion within it. The emergence of deism and the idea of a creator God who does not intervene in the world reflects the changing intellectual and cultural landscape of this period.

The Phenomenology of Neolithic Religion and Consciousness

Ritual and animism are distinct but related concepts that offer insights into the workings of the emotional and preconscious mind. While they are often associated with religious or spiritual practices, they can also be understood as psychological processes that serve important functions in human development and well-being (Edinger, 1972; Neumann, 1955).

Animism can be defined as the attribution of consciousness, soul, or spirit to objects, plants, animals, and natural phenomena. From a psychological perspective, animism involves “turning down” one’s cognitive functioning to “hear” the inner monologue of the world and treat it as alive. This process allows individuals to connect with the preconscious wisdom of their own psyche and the natural world (Tylor, 1871).

Ritual, on the other hand, is a structured sequence of actions that are performed with the intention of achieving a specific psychological or social outcome. In depth psychology, ritual is understood as a process of projecting parts of one’s psyche onto objects or actions, modifying them, and then withdrawing the projection to achieve a transformation in internal cognition (Moore & Gillette, 1990).

It is important to note that animism and ritual are not merely primitive or outdated practices, but rather reflect a natural state of human consciousness that has been suppressed or “turned off” by cultural and environmental changes, rather than evolutionary ones. This natural state can still be accessed through various means, including psychosis, religious practices, and intentional ritualistic behaviors (Grof, 1975).

The Changing Nature of Psychotic Experience

Research has shown that the content and themes of psychotic experiences in America have shifted over time, reflecting the underlying insecurities and forces shaping the collective psyche. Before the Great Depression, psychotic experiences were predominantly animistic, with people hearing “spirits” tied to natural phenomena, geography, or ancestry. These experiences were mostly pleasant, even if relatively disorganized.

However, as society shifted from an agrarian to an industrial and then to a post-industrial economy, the anxieties and insecurities of each era found expression through the content of psychotic experiences. The voices became more fearful, antagonistic, and focused on themes of hierarchical control through politics, surveillance, and technology.

These changes in the nature of psychosis reflect the evolution of collective trauma and the manifestation of unintegrated preconscious elements in the American psyche. Interestingly, UFO conspiracy theories have emerged as a prominent manifestation of these unintegrated preconscious elements in the modern era, involving themes of surveillance, control, and the supernatural. These theories can be seen as a way for individuals to make sense of their experiences of powerlessness and disconnection in a rapidly changing world, by attributing them to external, otherworldly forces.

The changing nature of psychotic experiences highlights the profound impact that societal and environmental stressors can have on the preconscious mind. By understanding how these stressors shape the content and themes of psychosis, we can gain insight into the deeper anxieties and insecurities that plague the collective psyche. This understanding can inform more comprehensive and compassionate approaches to mental health treatment, which address not only the symptoms of psychosis but also the underlying social and cultural factors that contribute to its development.

Ritual as a Psychological Process

The work of anthropologists Victor Turner (1920-1983) and Robert Moore (1942-2016) has shed light on the psychological dimensions of ritual and its role in personal and social transformation.

Turner’s concepts of liminality (the transitional state in ritual where participants are “betwixt and between”) and communitas (the sense of equality and bond formed among ritual participants) highlight the transformative potential of ritual. By creating a safe, liminal space for psychological exploration and change, ritual can help individuals process and integrate traumatic experiences and achieve personal growth (Turner, 1969).

Moore, in his books “King, Warrior, Magician, Lover” (1990) and “The Archetype of Initiation” (2001), emphasized the importance of ritual in modern society for personal development and social cohesion. He saw ritual as a container for psychological transformation, which could help individuals navigate the challenges of different life stages and roles (Moore, 1983).

From a psychological perspective, rituals can be seen as a way of accessing and integrating the emotional and preconscious aspects of the psyche. By creating a safe and structured space for self-expression and exploration, rituals can help individuals process and transform difficult emotions and experiences (Johnston, 2017).

Animism and Psychological Evolution

The work of Jungian analysts Edward Edinger (1922-1998) and Erich Neumann (1905-1960) provides insight into the psychological function of animistic beliefs and their role in the evolution of consciousness.

Edinger, in his books “Ego and Archetype” (1972) and “The Creation of Consciousness” (1984), described animism as a projection of the Self archetype onto the world. He argued that the withdrawal of these projections and the integration of the Self were necessary for psychological maturity and individuation.

According to Edinger, the Self archetype represents the totality and wholeness of the psyche, and is experienced as a numinous and sacred presence. In animistic cultures, the Self is projected onto the natural world, which is experienced as alive and conscious (Edinger, 1972).

Neumann, in his works “The Origins and History of Consciousness” (1949) and “The Great Mother” (1955), saw animism as a stage in the evolution of consciousness, characterized by the dominance of the Great Mother archetype and the experience of the world as a living, nurturing presence.

Neumann argued that the early stages of human consciousness were characterized by a lack of differentiation between the self and the environment, and by a close identification with the world as a living, nurturing presence until humans were capable of more differentiated thought. This understanding of animism as a stage in the psychological evolution of humanity provides insight into the ways in which our relationship with the natural world and the unconscious mind has changed over time, and the challenges we face in integrating these aspects of our experience in the modern world.

The integration of these varied perspectives on animism, ritual, and the evolution of consciousness offers a rich and nuanced understanding of the psychological dimensions of Neolithic religion and cognition. By recognizing the ways in which these ancient practices and beliefs reflect the workings of the preconscious mind and the processes of psychological transformation, we can gain insight into the enduring significance of these traditions for the human psyche and the challenges of living in an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world.

What is the Self?

How do we define “the self” or even “conciousness” when it is clear that these are shifting and maleable conceepts reliant on cultural, societal, and technological realities of the environments we inhabit. The concept of the self lies at the heart of the psychotherapeutic endeavor, yet it remains one of the most elusive and paradoxical ideas in the field. As thinkers from various disciplines have long recognized, the self is not a static, monolithic entity that can be easily defined or quantified, but a fluid, multidimensional process that emerges from the complex interplay of consciousness and unconsciousness, internal and external worlds, past and present experiences.

This understanding of the self poses significant challenges for the dominant paradigms of contemporary psychotherapy, which often rely on overly reductionistic, hyper-rational models that seek to isolate and target specific symptoms or behaviors. While these approaches have their place, they risk overlooking the deeper, more holistic dimensions of the self that are essential for genuine healing and transformation.

The Paradoxical Nature of the Self

At the core of the self’s paradoxical nature is the fact that it is both a subjective experience and an objective reality, a product of our individual consciousness and a reflection of the broader cultural and societal forces that shape us. As the philosopher William James observed, the self is not a single, unified entity, but a “bundle of perceptions” that is constantly shifting and evolving in response to our changing circumstances and experiences.

This multifaceted nature of the self is further complicated by the fact that we often hold contradictory or inconsistent beliefs and values, both within ourselves and in relation to others. We may present a certain image or persona to the world, while simultaneously harboring doubts, fears, or secret desires that we keep hidden from view. We may express one set of opinions or attitudes in public, while privately struggling with a very different set of feelings or convictions.

These internal conflicts and inconsistencies are not simply signs of weakness or pathology, but fundamental aspects of the human condition. They reflect the fact that the self is not a fixed, unchanging essence, but a dynamic, evolving process that is shaped by a complex interplay of biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors.

The Limits of Reductionism

Despite this complexity, much of contemporary psychotherapy continues to operate within a framework of reductionism, seeking to isolate and target specific symptoms or behaviors as if they were independent entities that could be treated in isolation. This approach is rooted in the biomedical model, which views mental health issues as discrete, diagnosable conditions that can be effectively treated through standardized interventions.

While this model has its place, it risks overlooking the deeper, more holistic dimensions of the self that are essential for genuine healing and transformation. By focusing narrowly on specific symptoms or behaviors, it fails to account for the complex web of relationships, experiences, and meanings that shape our sense of self and our way of being in the world.

Moreover, this reductionistic approach often relies on an overly rational, cognitive framework that privileges conscious, verbal processing over the more intuitive, embodied, and symbolic dimensions of experience. This can lead to a kind of “talking cure” that may provide temporary relief or insight, but fails to address the deeper, more unconscious aspects of the self that are often the root of our suffering.

Trauma, Neurobiology, and the Nature of Ritual

Recent studies in neuroscience and comparative psychology have shed light on the remarkable similarities between the social and cognitive capacities of humans and other highly intelligent, social species, particularly in relation to the religious and meaning-making functions of the brain. These findings suggest that the evolutionary development of these functions may be rooted in the social and emotional needs of complex, social beings.

In humans, the religious and meaning-making functions of the brain are associated with a complex network of neural structures, including the prefrontal cortex, the limbic system, and the temporal lobes. These regions are involved in various aspects of religious experience, such as the formation of beliefs, the experience of emotions, and the attribution of meaning to events and symbols.

One key structure in this network is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which plays a role in the experience of empathy, social bonding, and the processing of emotional and spiritual experiences. The ACC is also involved in the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, which may explain the intense physiological responses (e.g., chills, tears) that often accompany religious experiences.

Trauma, in particular, can have a profound impact on the brain and its capacity for religious and meaning-making experiences. Traumatic experiences can lead to a profound fragmentation of the psyche, as the individual’s sense of self and connection to others is shattered by overwhelming fear, helplessness, and horror.

In response to trauma, the brain may develop dissociative mechanisms that allow the individual to compartmentalize and detach from the painful memories and emotions associated with the traumatic event. These dissociative states can manifest as alterations in consciousness, identity, and memory, and may be accompanied by a sense of disconnection from the body and the environment.

The potential of ritual for facilitating trauma healing is supported by recent research in neurobiology and attachment theory. Studies have shown that the experience of safe, attuned relationships can help to regulate the brain’s stress response system and promote the growth of new neural pathways associated with emotional regulation and resilience.

Ritual, with its emphasis on embodied, relational experience and the creation of safe, structured spaces for exploration and transformation, may serve as a powerful tool for promoting the neurobiological and psychological processes associated with trauma healing.

By recognizing the ways in which trauma can impact the brain and the psyche, and by drawing upon the insights of neurobiology, attachment theory, and the study of ritual and meaning-making practices, therapists can develop more effective and integrative approaches to working with individuals who have experienced traumatic events.

This may involve incorporating embodied, experiential practices such as mindfulness, movement, and expressive arts into the therapeutic process, as well as creating safe, structured spaces for the exploration and integration of traumatic memories and emotions.

It may also involve working with clients to develop a more integrated and coherent sense of self, through the use of symbolic and metaphorical language, the exploration of archetypes and myths, and the cultivation of safe, attuned relationships.

Ultimately, by recognizing the complex interplay of neurobiology, attachment, and meaning-making practices in the healing of trauma, therapists can help individuals to reconnect with their innate capacity for resilience, growth, and transformation, and to find a renewed sense of purpose and connection in their lives.

The Persistence of Religious Meaning-Making in Modern Culture

Recent studies in neuroscience and comparative psychology have shed light on the remarkable similarities between the social and cognitive capacities of humans and other highly intelligent, social species, particularly in relation to the religious and meaning-making functions of the brain. These findings suggest that the evolutionary development of these functions may be rooted in the social and emotional needs of complex, social beings.

In humans, the religious and meaning-making functions of the brain are associated with a complex network of neural structures, including the prefrontal cortex, the limbic system, and the temporal lobes. These regions are involved in various aspects of religious experience, such as the formation of beliefs, the experience of emotions, and the attribution of meaning to events and symbols.

One key structure in this network is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which plays a role in the experience of empathy, social bonding, and the processing of emotional and spiritual experiences. The ACC is also involved in the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, which may explain the intense physiological responses (e.g., chills, tears) that often accompany religious experiences.

Trauma, in particular, can have a profound impact on the brain and its capacity for religious and meaning-making experiences. Traumatic experiences can lead to a profound fragmentation of the psyche, as the individual’s sense of self and connection to others is shattered by overwhelming fear, helplessness, and horror.

In response to trauma, the brain may develop dissociative mechanisms that allow the individual to compartmentalize and detach from the painful memories and emotions associated with the traumatic event. These dissociative states can manifest as alterations in consciousness, identity, and memory, and may be accompanied by a sense of disconnection from the body and the environment.

Ritual and other embodied, experiential practices may play a crucial role in facilitating the healing and integration of traumatic experiences. By creating a safe, structured space for the expression and exploration of painful emotions and memories, ritual can help individuals reconnect with their bodies, their sense of self, and their connection to others.

The use of rhythmic, repetitive movements, vocalizations, and other sensory stimuli in ritual can help to regulate the autonomic nervous system and promote a sense of safety and stability. The experience of communitas, or the sense of equality and unity among ritual participants, can also help to counteract the isolation and disconnection that often accompany traumatic experiences.

Moreover, the symbolic and metaphorical dimensions of ritual can provide a language for expressing and integrating the fragmented aspects of the self. By engaging with archetypes, myths, and other symbolic narratives, individuals can find meaning and coherence in their experiences, and develop a more integrated and resilient sense of self.

The potential of ritual for facilitating trauma healing is supported by recent research in neurobiology and attachment theory. Studies have shown that the experience of safe, attuned relationships can help to regulate the brain’s stress response system and promote the growth of new neural pathways associated with emotional regulation and resilience.

Ritual, with its emphasis on embodied, relational experience and the creation of safe, structured spaces for exploration and transformation, may serve as a powerful tool for promoting the neurobiological and psychological processes associated with trauma healing.

By recognizing the ways in which trauma can impact the brain and the psyche, and by drawing upon the insights of neurobiology, attachment theory, and the study of ritual and meaning-making practices, therapists can develop more effective and integrative approaches to working with individuals who have experienced traumatic events.

This may involve incorporating embodied, experiential practices such as mindfulness, movement, and expressive arts into the therapeutic process, as well as creating safe, structured spaces for the exploration and integration of traumatic memories and emotions.

It may also involve working with clients to develop a more integrated and coherent sense of self, through the use of symbolic and metaphorical language, the exploration of archetypes and myths, and the cultivation of safe, attuned relationships.

Ultimately, by recognizing the complex interplay of neurobiology, attachment, and meaning-making practices in the healing of trauma, therapists can help individuals to reconnect with their innate capacity for resilience, growth, and transformation, and to find a renewed sense of purpose and connection in their lives.

The Paradoxical Nature of Consciousness and the Role of Ritual in Integrating Objective and Subjective Experience

The conscious objective mind and the unconscious symbolic dimension are not separate entities and that is what makes religion, spirituality, and subjective experience so frustrating to study. They are woven together and blended in a way that is partially homogenous and partially heterogeneous, making our consciousness both a particle and a wave. Put more bluntly, the conscious and unconscious mind are both separate and opposing and entirely blended in an inseparable way. The paradoxical nature of our consciousness is what makes paganism both hard to define and inevitable. Primitive pagans lived in a more conversational paradigm with the unconscious, being a more actively acknowledged part of their experience. This is not wrong but also not the end of the progression of how we should integrate religion and pagan “gods” into our psyche, communities and culture.

We must acknowledge that science itself, despite its reliance on empirical observation and mathematical rigor, is ultimately a quest to reconcile the paradoxes that permeate our existence. While language, psychology, and philosophy grapple with paradox through the metaphorical fabric of the human mind, science seeks to untangle these knots through the language of mathematics and the systematic interrogation of nature’s mysteries.

The Double-Slit Experiment and the Paradox of Consciousness

The double-slit experiment, one of the most famous and perplexing experiments in the history of physics, has revealed the fundamental paradox of light’s nature as both a particle and a wave. This discovery has profound implications not only for our understanding of the physical world but also for our conception of human consciousness and the relationship between the conscious and unconscious mind.

Like the interference pattern that emerges in the double-slit experiment, the interplay between the conscious and unconscious creates a complex tapestry of experience, one that defies simple categorization or control. From one perspective, as W.H. Auden suggests, we are “lived through” by forces we cannot comprehend, our lives shaped by the unseen currents of the unconscious. In this view, our sense of autonomy is an illusion, a mere epiphenomenon of the deeper, more primal drives that animate our being.

Yet, from another vantage point, we are indeed separate, independent beings, capable of exerting our will and shaping our destinies through the power of conscious choice. This perspective emphasizes the role of personal agency, the belief that we are the masters of our own fate, even as we navigate the complex interplay of internal and external forces.

The truth, as with the nature of light, lies in the paradoxical unity of these seemingly contradictory aspects. Our conscious and unconscious minds are not separate entities but rather two facets of a single, indivisible whole. They are simultaneously distinct and interconnected, each influencing and shaping the other in a constant dance of creation and destruction, revelation and concealment.

This paradoxical relationship is reminiscent of the wave-particle duality of light, where the same entity can exhibit both wave-like and particle-like properties depending on the context and the mode of observation. In the same way, our conscious and unconscious minds are both fundamentally different and fundamentally the same, two aspects of a unified consciousness that transcends the limitations of linear thinking and binary oppositions.

By embracing this paradox, we can begin to navigate the complexities of our inner world with greater wisdom and compassion. We can learn to honor the power of our unconscious impulses and intuitions while also cultivating the clarity and focus of our conscious mind. We can recognize that our sense of self is not a fixed and immutable entity but rather a dynamic and ever-changing landscape, shaped by the constant interplay of light and shadow, reason and emotion, control and surrender.

By engaging in the delicate dance between the rational and the intuitive, the self-directed and the unconsciously driven, we open ourselves to a more profound understanding of our own nature and the world around us. It is in the reconciliation of these paradoxes, in the acceptance of the complex interplay between the conscious and unconscious, that we find the key to unlocking our full potential and navigating the rich, multifaceted landscape of our existence.

On Science and Consciousness in Paganism

In the history of scientific inquiry, we find that the most profound breakthroughs emerge not from pure logic or calculation, but from the fertile soil of human intuition and the unconscious mind. Visionaries like Einstein, Oppenheimer, Grosseteste, and Kekulé did not stumble upon their revelations through empirical observation alone. No, their triumphs were preceded by flashes of insight, subjective leaps of imagination that dared to envision new possibilities beyond the boundaries of conventional thinking.

Einstein, for example, often spoke of the role of intuition and imagination in his scientific work. He once famously said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.” His groundbreaking theories of relativity were not simply the result of mathematical calculations, but were born from a deep intuitive understanding of the nature of space, time, and gravity.

Similarly, the chemist August Kekulé’s discovery of the structure of the benzene molecule is said to have come to him in a dream, in which he saw a snake biting its own tail, forming a ring. This intuitive leap allowed him to envision the circular structure of the benzene ring, a discovery that revolutionized the field of organic chemistry.

In quantum physics, the work of pioneers like Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg was deeply influenced by their philosophical and metaphysical insights. Bohr’s concept of complementarity, which held that the wave and particle nature of matter were both necessary for a complete understanding of reality, was not simply a mathematical formulation, but a profound intuitive insight into the nature of the universe.

Scientific discovery is not a purely rational or objective process, but is deeply intertwined with the subjective experiences and unconscious minds of the scientists themselves. The unconscious mind, with its vast reservoir of intuitive knowledge and symbolic associations, plays a crucial role in the creative process of scientific inquiry.

We must recognize that science is not a mere exercise in dispassionate rationality, but rather a means of translating the ineffable whispers of the unconscious into the tangible vernacular of empirical knowledge. For it is the unconscious forces of nature, imagination, and mysticism that serve as the primordial wellsprings of human understanding, the fertile ground from which all scientific inquiry ultimately springs.

Yet, in our modern, technocratic age, we have lost sight of this fundamental truth. Seduced by the allure of pure reason and the false promise of complete mastery over the natural world, we have severed our connection to the pagan roots that once infused our ancestors’ relationship with the cosmos. We have come to see ourselves as purely logical creatures, endowed with the gift of conscious thought, while denying the deeper wellsprings of our emotional and intuitive selves.

Through our economic systems, social programming, and bureaucratic structures, we have constructed an artificial edifice that obscures the paradoxical truths at the heart of our existence. We have forgotten that we are not disembodied intellects, but rather emotional beings first and foremost, creatures of soul and blood, inextricably intertwined with the rhythms and mysteries of the natural world.

In this sense, we are all pagans, whether we acknowledge it or not. The pagan essence that once guided our ancestors in their quest to understand the cosmos still burns within us, awaiting rediscovery and reintegration into our modern ways of being. For it is only by reconnecting with these pagan wellsprings, by embracing the paradoxes that define our existence and the primacy of the unconscious mind, that we can fully unlock the creative potential of human understanding.

Science, then, becomes a modern form of paganism, a means of unveiling the sacred mysteries that permeate the natural world and the depths of our own consciousness. By acknowledging the role of intuition, imagination, and the unconscious as the wellsprings of scientific discovery, we can reclaim our rightful place as creatures of paradox, ever seeking to reconcile the ineffable truths that lie at the heart of existence.

Ritual as a Tool for Integrating Objective and Subjective Experience

Ritual, in this context, can be understood as a sophisticated technology for integrating the objective and subjective dimensions of human experience. By engaging in symbolic actions, gestures, and invocations, ritual creates a bridge between the conscious ego and the unconscious psyche, allowing for a deeper communication and integration of these often disparate aspects of the self.

At its core, ritual is a means of externalizing and manipulating internal psychological states through the use of symbols and metaphors. By projecting parts of the psyche onto objects, actions, or other participants, ritual allows individuals to engage with their unconscious material in a tangible and embodied way. This process of externalization and manipulation can lead to a transformation of internal cognition, as the individual withdraws the projection and integrates the insights and experiences gained through the ritual process.

In this sense, ritual can be seen as a form of “spicy cognition,” a way of playing with the paradoxical nature of consciousness and the complex interplay between objective and subjective reality. By suspending the usual rules and constraints of everyday life, ritual creates a liminal space in which new possibilities can emerge, and new ways of understanding the self and the world can be explored.

Moreover, ritual serves as a container for the exploration and enactment of mythic themes and archetypal patterns, providing a structure and a language for engaging with the deeper dimensions of the psyche. Through the use of symbolic actions, mythic narratives, and archetypal imagery, ritual allows individuals to connect with the universal aspects of human experience and to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

In this way, ritual can be seen as a powerful tool for psychological healing and transformation. By creating a safe and structured space for the integration of unconscious material, ritual can help individuals to process traumatic experiences, resolve inner conflicts, and develop a more coherent and authentic sense of self.

However, it is important to recognize that ritual is not a panacea, and that it can also be used in ways that are harmful or oppressive. When ritual becomes rigid, dogmatic, or disconnected from the authentic needs and experiences of the individual, it can serve to reinforce existing power structures and limit personal growth and transformation.

Therefore, the use of ritual in a therapeutic or transformative context requires a deep sensitivity and attunement to the unique needs and experiences of each individual. It requires a willingness to engage with the paradoxical and often messy nature of the human psyche, and to hold space for the emergence of new insights and possibilities.

Ultimately, ritual is a tool for navigating the complex landscape of human consciousness, for integrating the objective and subjective dimensions of experience, and for facilitating a deeper connection to the self, the community, and the larger web of life. By embracing the power of ritual and the paradoxical nature of consciousness, we can begin to unlock the transformative potential of the human psyche and to create a more authentic and meaningful existence.

Philosophy, Anthropology, and Religion as Games of Object Relations

The exploration of ritual and its role in integrating objective and subjective experience leads us to a provocative insight: that philosophy, anthropology, and religion may be, at their core, sophisticated games of object relations. These disciplines, which seek to understand the nature of reality, the human condition, and our place in the cosmos, can be seen as elaborate systems for projecting and manipulating internal psychological states onto external objects, concepts, and narratives.

In this view, philosophical inquiry becomes a means of externalizing and examining the deep structures of human thought and experience. By engaging with abstract concepts and logical arguments, philosophers create a symbolic space in which the unconscious patterns and assumptions of the mind can be made visible and subjected to critical analysis. Through this process of externalization and reflection, new insights and understandings can emerge, leading to a transformation of internal cognition and a deeper appreciation of the nature of reality.

Anthropology, similarly, can be understood as a way of projecting and exploring the unconscious dimensions of human culture and society. By immersing themselves in the beliefs, practices, and symbolic systems of different cultures, anthropologists create a mirror in which the hidden assumptions and biases of their own culture can be reflected and examined. Through this process of cross-cultural comparison and analysis, new understandings of the human condition can emerge, and the boundaries of the self can be expanded to include a greater diversity of human experience.

Religion, perhaps most explicitly, can be seen as a game of object relations writ large. Through the creation of mythic narratives, symbolic rituals, and sacred objects, religion provides a structure and a language for externalizing and engaging with the deepest aspects of the human psyche. By projecting unconscious fears, desires, and aspirations onto divine figures and cosmic forces, religion allows individuals and communities to grapple with the ultimate questions of existence and to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

However, just as with ritual, these games of object relations can also be used in ways that are limiting or oppressive. When philosophy, anthropology, or religion become dogmatic, rigid, or disconnected from the authentic experiences of individuals and communities, they can serve to reinforce existing power structures and limit personal and collective growth.

Therefore, the use of these disciplines as tools for psychological and spiritual transformation requires a deep awareness of their nature as games of object relations. It requires a willingness to engage with the paradoxical and often messy nature of human experience, and to hold space for the emergence of new insights and possibilities.

Ultimately, by recognizing philosophy, anthropology, and religion as sophisticated games of object relations, we can begin to use them more consciously and intentionally as tools for navigating the complex landscape of human consciousness. By embracing the power of these symbolic systems to externalize and transform internal psychological states, we can facilitate a deeper integration of the objective and subjective dimensions of experience and create a more authentic and meaningful existence.

It is through this process of playing with object relations, of projecting and manipulating internal states through external symbols and narratives, that we can begin to transcend the limitations of our individual perspectives and connect with the deeper patterns and mysteries of the cosmos.

The paradoxical nature of consciousness, the complementarity of the conscious and unconscious mind, and the complex dance between objective and subjective realities all point to the importance of embracing complexity, ambiguity, and paradox in our quest for understanding and transformation.

By engaging in sophisticated games of object relations, whether through ritual, philosophy, anthropology, or religion, we can begin to navigate this complex terrain with greater skill and awareness. We can learn to hold space for the emergence of new insights and possibilities, to embrace the creative tension between opposing forces, and to find meaning and purpose in the midst of uncertainty and change.

Ultimately, it is through this process of creative engagement with the paradoxes of existence that we can begin to unlock the transformative potential of human consciousness and create a more authentic, meaningful, and connected way of being in the world.

The Blind Spot of Clinical Psychology in a Consumerist Culture

As we’ve seen, the world of advertising and consumerism relies heavily on psychological manipulation to influence behavior and shape identities. From the early days of Edward Bernays applying his uncle Sigmund Freud’s ideas to sell cigarettes to women, to the archetypal branding strategies of contemporary marketing gurus like Clotaire Rapaille, the commercial persuasion industry has long been mining the insights of depth psychology to hook consumers.

And yet, the field of clinical psychology has remained largely silent on the impacts of living in a society saturated with psychologically manipulative messaging. In focusing narrowly on the treatment of individual symptoms and disorders, the profession has often failed to grapple with the larger cultural and economic forces shaping the modern psyche.

This blind spot is particularly troubling given the growing evidence of the toxic effects of consumerist culture on mental health and well-being. As thinkers like Guy Debord, Erich Fromm, and Jean Baudrillard have argued, life in the society of the spectacle is profoundly alienating, reducing authentic human experience to a never-ending stream of seductive images and simulations. Consumerism promotes an “having mode” of existence, focused on acquisition and status display, rather than the “being mode” of creative self-expression and direct relation to others.

Despite the clear relevance of these issues to mental health, clinical psychology as a field has been largely complicit in the reification of the consumerist status quo. The dominant models of psychotherapy remain focused on adjusting the individual to the demands of the market society, rather than questioning the psychological toxicity of that society itself.

This complicity is in part a function of the increasing corporatization of the mental health industry, with its emphasis on efficiency, standardization, and return on investment. In a healthcare system dominated by insurance companies and pharmaceutical interests, there is little incentive to explore the social and economic roots of psychological distress.

But it also reflects a deeper philosophical alignment between the consumerist worldview and the dominant epistemologies of mainstream psychology. Both are grounded in a radically atomized conception of the self, cut off from history, tradition, and community. Both substitute superficial notions of “happiness” and “success” for more substantive visions of the good life. And both privilege a narrow, instrumental rationality over more holistic and embodied ways of knowing.

The result is a kind of “junk food” approach to mental health, peddling quick-fix coping strategies and feel-good bromides rather than nourishing the deeper sources of meaning and connection. Just as processed food corporations exploit our evolutionary cravings for sugar, salt, and fat to keep us craving more of their products, the happiness industry exploits our yearning for wholeness by selling us dissociated surrogates for authentic well-being.

Breaking free of this simulacrum of mental health will require a radical reassessment of the social role of clinical psychology. Rather than serving as a band-aid for the inevitable casualties of consumer capitalism, the profession must become a force for cultural transformation in solidarity with other emancipatory movements.

This means, first and foremost, cultivating a critical consciousness about the structural causes of psychological distress in modern society. It means training clinicians to recognize and address the impacts of economic inequality, social alienation, and ecological crisis on individual and collective psyches. And it means developing new models of therapeutic practice that center the cultivation of autonomy, solidarity, and creative resistance.

On a theoretical level, a truly liberatory psychology must break with the reductionist and individualist assumptions of the biomedical model to embrace a more holistic, dialectical understanding of the relationship between person and society. This requires a recovery of the rich tradition of humanistic, existential, and critical approaches within the field, as well as an openness to cross-fertilization with other disciplines like social ecology, political economy, and cultural studies.

At the same time, a post-consumerist clinical psychology must also work to build alternative institutions and practices outside the mainstream mental health system. This could include the creation of grassroots support networks, peer counseling collectives, and community-based therapeutic spaces grounded in an ethos of mutual aid and participatory democracy. By modeling forms of care that prefigure the kind of society we wish to create, these initiatives can serve as “laboratories of the revolution” for a more emancipatory approach to mental health.

Ultimately, the project of liberating the psyche from the grip of consumer culture must be part of a broader struggle for social and ecological transformation. Only by changing the material conditions of existence can we hope to create a world conducive to authentic sanity and well-being. This will require nothing less than a revolutionary restructuring of the way we live, work, and relate to each other and the natural world.

For clinical psychology to play a meaningful role in this transformation, it must first confront its own complicity in the perpetuation of consumerist alienation. It must shed its pretensions of political neutrality to become an active force for systemic change. And it must anchor itself in a vision of the good life based not on the maximization of individual utility, but on the realization of our collective potential for creativity, compassion, and connection.

This is no small task, and it will not happen overnight. But as the contradictions of consumer capitalism become ever more glaring, and its human and ecological costs ever more intolerable, the need for a radical reimagining of mental health grows increasingly urgent. By rising to this challenge, psychology can help to light the way toward a future beyond the Spectacle – a future in which we can finally be at home in our own minds, and in the world we share with all living beings.

Of course, this path of resistance is fraught with uncertainty and risk. Consumer culture excels at absorbing and domesticating even the most radical critiques, and the pull of conformism is strong. There are no easy formulas or guarantees of success. But as Herbert Marcuse argued in One-Dimensional Man, the very totalizing nature of the system inevitably generates its own negation. Even within the belly of the consumerist beast, the seeds of a new society are always germinating, waiting for the right conditions to sprout.

The Paradox of the Objective and Subjective Mind

As Jungian analyst Edward Edinger points out, the objective and subjective parts of the brain evolved separately to perform distinct functions. The objective mind, centered in the neocortex, is responsible for logical reasoning, language, and abstract thinking. It is the part of us that navigates the external world, makes plans, and solves problems based on empirical reality.

The subjective mind, on the other hand, is rooted in the older, more primitive parts of the brain – the limbic system and the brainstem. It is the realm of emotions, intuitions, and unconscious impulses. This is the part of us that experiences the world in a direct, pre-verbal way, through the filter of our individual history, memories, and associations.

These two modes of consciousness could not be more different, and as Edinger observes, they often struggle to coexist within the same individual. The objective mind seeks clarity, consistency, and linear causality, while the subjective mind traffics in ambiguity, paradox, and symbolic resonance. The former tries to master reality through analysis and control, while the latter surrenders to the mystery and allows itself to be moved by the numinous.

In the modern world, with its emphasis on scientific rationality and technological mastery, the objective mind has been elevated to a place of supreme authority. The subjective dimensions of experience are often dismissed as irrelevant, irrational, or even pathological. The result is a kind of psychic imbalance, where the ego identifies solely with its objective functions and represses or denies its subjective roots.

This imbalance is reflected in the dominant paradigms of clinical psychology, which tend to view mental health through a narrow, medicalized lens. Symptoms are seen as discrete entities to be eliminated through targeted interventions, rather than as symbolic expressions of a deeper psychic reality. The goal of therapy becomes adjustment and adaptation to external norms, rather than the integration and individuation of the whole self.

However, as Edinger suggests, the objective and subjective minds cannot be neatly compartmentalized or hierarchically arranged. They represent complementary and mutually interdependent aspects of the psyche that must be brought into dynamic relation with each other. Attempts to suppress or eliminate the subjective in favor of the objective only lead to further fragmentation and alienation.

The key to psychic wholeness lies not in the triumph of one mode over the other, but in the cultivation of what Edinger calls “the transcendent function” – the ability to hold the tension of opposites and allow a third, integrative perspective to emerge. This is not a matter of rationally reconciling contradictions or finding a logical middle ground, but of surrendering to the symbolic process and allowing it to transform both poles of the dialectic.

The language of this transformation is the language of metaphor, myth, and dream. These are the ways in which the subjective mind communicates its truths to the objective mind, not through literal correspondences but through figurative resonances. By engaging with the images and stories that emerge from the depths of the psyche, we can start to build a bridge between the two worlds and foster a more integrated, fully human consciousness.

This is where the role of the therapist becomes crucial. In order to help patients access and integrate their subjective experience, therapists must themselves be fluent in the language of the unconscious. They must be able to recognize and amplify the symbolic dimensions of a patient’s narrative, not just its literal content. And they must be willing to enter into the messiness and uncertainty of the subjective realm, without trying to prematurely impose order or clarity.

Unfortunately, this kind of symbolic literacy is often lacking in the training of contemporary clinicians. The emphasis on evidence-based practice and standardized protocols leaves little room for the cultivation of intuition, imagination, and metaphorical thinking. Therapists are taught to view their patients’ experiences through the lens of diagnostic categories and treatment algorithms, rather than as unique, meaning-laden expressions of an individual soul.

To truly heal the split between the objective and subjective minds, both in individual patients and in the larger culture, we need a radically different approach to mental health – one that honors the wisdom of the unconscious and recognizes the transformative power of symbol and metaphor. This means training therapists to be attuned to the poetic dimensions of language, to the subtle cues and resonances that point beyond the literal to the figurative. It means creating therapeutic spaces that invite the emergence of the numinous, through practices like active imagination, dream work, and expressive arts. And it means fostering a culture of shared meaning-making, where the insights and epiphanies of the subjective mind can be valued and integrated into our collective understanding.

This is not to suggest that the objective mind should be abandoned or denigrated. On the contrary, the capacity for rational analysis and empirical observation is a vital aspect of our humanity, and has given rise to extraordinary achievements in science, technology, and social organization. The point is not to reject objectivity, but to recognize its limitations and to bring it into a more balanced and dynamic relationship with subjectivity.

In practical terms, this might mean incorporating more experiential and imaginal elements into the training of therapists, alongside the traditional emphasis on theory and technique. It might mean developing new diagnostic frameworks that honor the symbolic and narrative dimensions of psychological distress, rather than reducing it to a checklist of symptoms. And it might mean creating more opportunities for therapists and patients to engage in collaborative meaning-making, through practices like co-created storytelling, ritual, and the interpretation of dreams and synchronicities.

At a broader societal level, the cultivation of a more integrated relationship between the objective and subjective minds will require a fundamental shift in our values and priorities. It will require us to challenge the dominance of instrumental reason and to make space for the non-rational, the intuitive, and the imaginal in our public discourse and decision-making. It will require us to value emotional intelligence and creative expression as much as we value analytical prowess and technical expertise. And it will require us to recognize that the health and wholeness of individuals and communities depends not just on the satisfaction of material needs, but on the nourishment of the soul through shared meaning and purpose.

Ultimately, the split between the objective and subjective minds reflects a deeper alienation of the modern self from its own depths and from the living world around it. By learning to bridge that split through the cultivation of symbolic consciousness, we can start to heal that alienation and to restore a sense of enchantment and participation to our individual and collective lives.

This is the great task of a truly integrative psychology – to midwife the birth of a new kind of consciousness that honors both the rigor of reason and the wisdom of the unconscious. It is a task that will require us to venture into uncharted territory, both within ourselves and in the world around us. But it is also a task that holds the promise of a more whole and vibrant way of being human – one that can meet the challenges of our time with creativity, compassion, and a deep attunement to the mysteries of existence.

In the end, the objective and subjective minds are not really separate at all, but are two faces of the same deeper reality – the reality of the psyche itself, which weaves together matter and spirit, nature and culture, the personal and the transpersonal in an endlessly creative dance. By learning to participate more fully in that dance, we can begin to heal the wounds of a civilization that has lost touch with its own soul, and to create a world that nurtures the full spectrum of human possibility.

This is the vision that animates a depth-oriented, symbolically literate approach to psychotherapy – a vision of the human being not as a machine to be fixed or a problem to be solved, but as a living mystery to be embraced in all its paradox and complexity. It is a vision that calls us to a new kind of clinical practice, one that is not just about treating disorders but about facilitating the emergence of a more integrated, more fully realized self.

Of course, this is not an easy or straightforward path. It requires us to confront the shadows and contradictions within ourselves and our society, to grapple with the often uncomfortable truths of the unconscious, and to let go of our illusions of certainty and control. It requires us to cultivate a new kind of intellectual humility, one that recognizes the limits of our rational understanding and is willing to be transformed by the encounter with mystery.

But for those who are called to this work, there is also a great joy and liberation in it. For in learning to embrace the paradoxes of the psyche, we also come into a deeper, more authentic relationship with ourselves and with the world around us. We begin to experience life not as a problem to be solved, but as a profound and multi-dimensional adventure of consciousness, full of beauty, terror, and endless surprise.

And as we do this work of integration within ourselves, we also contribute to the larger work of cultural and planetary transformation. By helping to midwife the birth of a new kind of human being – one that is more whole, more creative, more alive to the sacredness of existence – we participate in the great unfolding story of the universe itself.

This is the deeper purpose of a truly integrative psychology – to serve as a catalyst for the evolution of consciousness, both individual and collective. It is a purpose that transcends the narrow confines of any particular theory or technique, and that calls us to a constant process of growth, discovery, and self-surpassing.

So let us embrace that call, with all the courage and compassion we can muster. Let us dare to imagine a new kind of clinical practice, one that honors the full complexity of the human soul and that sees the work of healing not as a mechanical fix but as a sacred art. And let us never forget that in the end, the transformation we seek is not just for our patients, but for ourselves and for the world as a whole.

The Path Ahead

As we have seen, the journey towards a truly integrative, transformative psychotherapy is both challenging and profoundly necessary. By recognizing the limitations of reductionistic, medicalized models of the mind and embracing the embodied, symbolic, and paradoxical dimensions of human cognition and experience, we open the door to new possibilities for healing and growth.

The insights of anthropology and evolutionary biology reveal that the religious and the symbolic are not archaic or primitive, but fundamental to how we make meaning and navigate the world. Ancient and indigenous traditions offer wisdom about the transformative power of ritual, myth, and somatic practice that modern psychotherapy ignores at its peril. And emerging therapeutic models like EMDR, brainspotting, and parts-based therapy point the way towards approaches that can engage the multiple layers of the self and the paradoxical nature of healing.

However, realizing the potential of this new vision of psychotherapy will require more than just individual innovation and exploration. It will require a systemic shift in the priorities, incentives, and paradigms that shape the mental health field as a whole. We must create space and support for the kind of interdisciplinary collaboration and creative experimentation needed to develop and refine integrative models. We must challenge the dominance of reductionistic, medicalized frameworks and advocate for a more holistic, contextual understanding of the mind. And we must be willing to learn from and honor the wisdom of traditions and cultures beyond our own.

The stakes could not be higher. In a world increasingly shaped by trauma, disconnection, and the fragmentation of the self, the need for transformative approaches to healing has never been greater. By embracing the full complexity and paradox of the human mind – its embodied, symbolic, and religious dimensions – we open the door to new possibilities for both individual and collective transformation.

This is the great challenge and invitation of our time – to midwife the emergence of a psychotherapy that can truly meet the depths of the human condition. It will require humility, courage, and a willingness to step beyond the boundaries of the known. But the rewards – the possibility of healing wounds, bridging worlds, and reclaiming the wholeness of the self – are beyond measure.

In the end, the path forward is one of both remembering and reimagining. By reconnecting with the ancient, embodied wisdom of our species and the transformative power of ritual and symbolism, while simultaneously innovating new forms of theory and practice, we can craft a psychotherapy worthy of the complexity and potential of the human mind. In doing so, we may just rediscover the sacred heart of healing itself.

Read More About Evidence Based Practice and Research Psychology:

Lessons from the STAR*D Scandal

The Corporatization of Healthcare

Incentives in Evidence Based Practice

Healing The Modern Soul Series Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Healing the Modern Soul Appendix

Bibliography

Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. Vintage Books.

Baker, J. A. (2011). The peregrine. New York Review Books.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. Pantheon Books.

Cytowic, R. E., & Eagleman, D. M. (2011). Wednesday is indigo blue: Discovering the brain of synesthesia. MIT Press.

Durkheim, E. (1912). The elementary forms of the religious life. George Allen & Unwin.

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and archetype: Individuation and the religious function of the psyche. Shambhala Publications.

Eliade, M. (1949). The myth of the eternal return: Cosmos and history. Princeton University Press.

Eliade, M. (1959). The sacred and the profane: The nature of religion. Harcourt, Brace & World.

Frazer, J. G. (1922). The golden bough: A study in magic and religion (Abridged ed.). Macmillan.

Grof, S. (1975). Realms of the human unconscious: Observations from LSD research. Viking Press.

Jaynes, J. (1976). The origin of consciousness in the breakdown of the bicameral mind. Houghton Mifflin.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols. Doubleday.

Kandinsky, W. (1977). Concerning the spiritual in art. Dover Publications.

Kellogg, R. (1970). Analyzing children’s art. National Press Books.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1955). The structural study of myth. The Journal of American Folklore, 68(270), 428-444.

Malinowski, B. (1948). Magic, science and religion and other essays. The Free Press.

Moore, R., & Gillette, D. (1990). King, warrior, magician, lover: Rediscovering the archetypes of the mature masculine. HarperSanFrancisco.

Neumann, E. (1949). The origins and history of consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Neumann, E. (1955). The great mother: An analysis of the archetype. Princeton University Press.

Otto, R. (1917). The idea of the holy. Oxford University Press.

Ramachandran, V. S., & Hubbard, E. M. (2001). Synaesthesia—a window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(12), 3–34.

Simner, J., & Hubbard, E. M. (Eds.). (2013). The Oxford handbook of synesthesia. Oxford University Press.

Smilek, D., Dixon, M. J., Cudahy, C., & Merikle, P. M. (2002). Synesthetic color experiences influence memory. Psychological Science, 13(6), 548-552.

Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Aldine Publishing Company.

Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom. John Murray.

Ward, J. (2013). Synesthesia. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 49-75.

Further Reading

Abram, D. (2011). Becoming animal: An earthly cosmology. Vintage Books.

Armstrong, K. (1993). A history of God: The 4,000-year quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Ballantine Books.

Baring, A., & Cashford, J. (1991). The myth of the goddess: Evolution of an image. Arkana.

Campbell, J. (1988). The power of myth. Doubleday.

Eliade, M. (1958). Patterns in comparative religion. Sheed & Ward.

Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Bollingen Series LXXVI, Princeton University Press.

Frankl, V. E. (1946). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Freud, S. (1913). Totem and taboo. Hugo Heller.

Grof, S. (1988). The adventure of self-discovery. SUNY Press.

Halifax, J. (1982). Shaman: The wounded healer. Thames & Hudson.

Harner, M. (1980). The way of the shaman. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-visioning psychology. Harper & Row.

James, W. (1902). The varieties of religious experience: A study in human nature. Longmans, Green, and Co.

Jung, C. G. (1938). Psychology and religion. Yale University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1961). Memories, dreams, reflections. Pantheon Books.

Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak experiences. Ohio State University Press.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the soul: A guide for cultivating depth and sacredness in everyday life. HarperCollins.

Otto, R. (1958). The idea of the holy: An inquiry into the non-rational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational. Oxford University Press.

Ramachandran, V. S. (2011). The tell-tale brain: A neuroscientist’s quest for what makes us human. W. W. Norton & Company.

Sacks, O. (1995). An anthropologist on Mars: Seven paradoxical tales. Alfred A. Knopf.

Sheldrake, R. (1981). A new science of life: The hypothesis of formative causation. Blond & Briggs.

Tart, C. T. (1969). Altered states of consciousness: A book of readings. John Wiley & Sons.