How has Jungian philosophy changed overtime?

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4

Read More on Jung here:

The origins of Jungian thought

In the early 20th century, Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung embarked on a pioneering exploration of the human psyche that would revolutionize our understanding of the mind, spirituality, and the quest for meaning. Drawing upon his clinical work, personal experiences, and wide-ranging studies of world mythology, religion, and esoteric traditions, Jung developed a profound and provocative map of the psyche that continues to inspire seekers and scholars today.

At the heart of Jung’s work is the concept of individuation – the lifelong journey of psychological and spiritual development that leads to the realization of one’s unique wholeness and authenticity. For Jung, this journey requires a courageous reckoning with the hidden depths of the unconscious mind, a willingness to confront the shadow aspects of the personality, and an openness to the transformative power of symbols, dreams, and the imagination (Jung, 1921/1976).

In this essay, we will delve into the key concepts and themes of Jungian psychology, tracing their evolution over the course of Jung’s life and work. We will explore the dynamics of the ego and the Self, the personal and collective dimensions of the unconscious, the role of archetypes and symbols in shaping human experience, and the central importance of the individuation process. Along the way, we will consider the implications of Jung’s ideas for navigating the challenges of spiritual growth, mental health, and ecological awareness in our time.

By engaging with the depth and complexity of Jung’s thought, we can gain valuable insights into the workings of the psyche, the nature of the sacred, and the unfolding of human potential. At the same time, we must approach these ideas with discernment and humility, recognizing their limitations as well as their profound possibilities. As we shall see, the ultimate goal of Jungian psychology is not to provide a fixed set of answers but to catalyze a living, evolving dialogue between the conscious mind and the great mysteries of the unconscious.

-

Key Concepts in Jungian Psychology

To appreciate the scope and significance of Jung’s work, it is essential to grasp the key concepts that form the foundation of his psychological worldview. These include the ego and the Self, the personal and collective unconscious, archetypes and symbols, and the individuation process. By understanding these core ideas, we can begin to navigate the rich and complex terrain of the Jungian psyche.

a) The Ego and the Self

In Jungian theory, the ego represents the center of conscious identity, the “I” that navigates the demands of external reality and makes choices based on individual goals and values. The ego emerges from the vast matrix of the unconscious mind, like a small island rising from the depths of the ocean. Its task is to provide a stable basis for engaging with the world, while also maintaining contact with the deeper layers of the psyche (Jung, 1928/1960).

However, the ego is not the totality of the personality. Beyond the ego lies the Self, the archetype of wholeness and the regulating center of the psyche. The Self encompasses both conscious and unconscious elements, and serves as the guiding principle of the individuation process. While the ego tends to identify with a limited set of roles and attributes, the Self represents the fullness of one’s being, the “God within” that transcends the boundaries of the personal ego (Jung, 1944/1953).

For Jung, the relationship between ego and Self is crucial for psychological health and spiritual development. When the ego is too rigid or inflated, it can become cut off from the wisdom of the unconscious, leading to neurosis, stagnation, and a sense of alienation from one’s deeper nature. On the other hand, when the ego is too weak or permeable, it can be overwhelmed by the forces of the unconscious, resulting in psychosis or spiritual crisis (Jung, 1944/1953).

The task of individuation, then, is to establish a dynamic and harmonious relationship between ego and Self, in which the ego recognizes its relative place within the larger personality and becomes a vehicle for the realization of the Self’s creative potential. This requires a willingness to confront and integrate the shadow aspects of the psyche, as well as an openness to the guidance of symbols, dreams, and synchronicities that arise from the depths of the unconscious (Jung, 1928/1960).

b) The Personal and Collective Unconscious

Jung’s model of the psyche distinguishes between two layers of the unconscious mind: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious contains the forgotten or repressed contents of an individual’s life history, including memories, wishes, fears, and traumas that are not currently available to conscious awareness. This is the realm of complexes – emotionally charged clusters of ideas and images that can shape one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in unconscious ways (Jung, 1934/1950).

Beyond the personal unconscious lies the collective unconscious – a deeper, universal layer of the psyche that is shared by all human beings. The collective unconscious contains the archetypes, the innate patterns and potentials that structure human experience across cultures and throughout history. These include the great themes and motifs of world mythology, such as the hero’s journey, the wise old man, the great mother, and the trickster (Jung, 1936/1959).

For Jung, the collective unconscious represents the evolutionary heritage of the human species, the psychological matrix from which individual consciousness emerges. By tapping into its timeless wisdom and creative energies, we can gain a greater understanding of our place within the larger web of life and access the resources needed for personal and collective transformation (Jung, 1936/1959).

However, Jung also recognized the dangers of unconscious identification with archetypal forces, which can lead to inflation, fanaticism, and mass hysteria. He saw this dynamic at work in the rise of fascism and totalitarianism in his own time, as individuals and groups became possessed by archetypal energies that overwhelmed the rational ego (Jung, 1936/1959). The task of individuation, then, requires a critical and discerning relationship with the collective unconscious, one that honors its power and potential while also maintaining the autonomy and integrity of the conscious personality.

c) Archetypes and Symbols

Central to Jung’s understanding of the collective unconscious is the concept of archetypes – the universal patterns and motifs that shape human experience across time and culture. Archetypes are not fixed or literal images, but rather dynamic potentialities that can manifest in a wide variety of forms, from gods and goddesses to animals, objects, and abstract ideas (Jung, 1936/1959).

For Jung, archetypes are the building blocks of the psyche, the innate structures that give rise to the great themes and stories of human life. They are expressed through symbols – the language of the unconscious mind that points beyond literal meanings to deeper, more numinous realities. Symbols can take many forms, from dreams and visions to art, literature, and religious iconography (Jung, 1921/1976).

The task of individuation involves learning to recognize and engage with the archetypal dimensions of one’s own psyche, as well as the larger collective unconscious. By working with symbols and myths, one can tap into the wisdom and energy of the archetypes and integrate their power into conscious awareness. This process is not about identifying with archetypes in a literal or inflated way, but rather developing a relationship of dialogue and creative collaboration (Jung, 1944/1953).

For example, the hero archetype represents the ego’s journey of growth and self-discovery, as it confronts challenges, overcomes obstacles, and ultimately achieves a new level of wholeness and integration. By engaging with the hero myth in its various forms, from ancient epics to contemporary film and literature, one can gain insight into the universal patterns of human development and find guidance for one’s own path of individuation (Jung, 1944/1953).

Similarly, the anima and animus archetypes represent the contrasexual aspects of the psyche – the inner feminine within the male and the inner masculine within the female. By integrating these archetypes through dream work, active imagination, and other practices, one can achieve a greater balance and wholeness within the personality, as well as more authentic and fulfilling relationships with others (Jung, 1936/1959).

d) The Individuation Process

At the heart of Jung’s psychology is the concept of individuation – the lifelong process of psychological and spiritual development that leads to the realization of one’s unique wholeness and authenticity. Individuation is not a linear or predictable journey, but rather a spiraling, iterative process of self-discovery and self-creation, marked by periods of crisis, growth, and transformation (Jung, 1921/1976).

The individuation process begins with the encounter with the shadow – the repressed or rejected aspects of the personality that are often experienced as negative, shameful, or threatening. By confronting and integrating the shadow, one can reclaim the lost or disowned parts of the self and achieve a greater sense of wholeness and vitality (Jung, 1951/1959).

As the journey continues, one may encounter other archetypal figures and forces, such as the anima/animus, the wise old man/woman, and the Self. Each of these encounters represents an opportunity for growth and transformation, as well as a challenge to the ego’s limited sense of identity and control (Jung, 1944/1953).

Ultimately, the goal of individuation is not to achieve a static state of perfection, but rather to cultivate a dynamic, ongoing relationship between the ego and the Self, in which the conscious personality becomes a vehicle for the realization of one’s deepest potential. This requires a willingness to embrace the unknown, to tolerate ambiguity and paradox, and to remain open to the guidance of the unconscious (Jung, 1921/1976).

For Jung, the individuation process is not just a personal quest, but also a collective one. As individuals strive to realize their unique wholeness, they contribute to the evolution of the species as a whole, helping to birth a new level of consciousness and a more integrated, compassionate world (Jung, 1916/1966). In this sense, the journey of individuation is a sacred calling, a way of aligning oneself with the deeper currents of life and participating in the great work of cosmic evolution.

-

Jung’s Evolving Perspective: From Freud to Alchemy

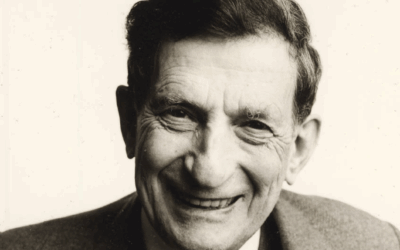

To fully appreciate the depth and complexity of Jung’s ideas, it is important to situate them within the context of his own intellectual and spiritual development. Jung began his career as a close collaborator of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, and was deeply influenced by Freud’s theories of the unconscious mind and the dynamics of repression and wish-fulfillment (Jung, 1961).

However, as Jung’s own experiences and clinical work deepened, he began to diverge from Freud in significant ways. While Freud emphasized the personal unconscious and the role of sexual drives in shaping the psyche, Jung came to see the unconscious as a much vaster and more creative realm, one that contained not only personal contents but also universal, archetypal patterns and energies (Jung, 1961).

Moreover, Jung became increasingly interested in the spiritual and mythological dimensions of the psyche, which he saw as essential for understanding the deeper meaning and purpose of human life. He began to study a wide range of religious and esoteric traditions, from Gnosticism and alchemy to Taoism and Hinduism, in order to gain insight into the timeless wisdom of the collective unconscious (Jung, 1961).

In particular, Jung was fascinated by the symbolic language of alchemy, which he saw as a powerful metaphor for the process of psychological transformation. Just as the alchemists sought to transmute base metals into gold, Jung believed that the task of individuation was to transform the raw materials of the unconscious into the gold of self-realization (Jung, 1944/1968).

Through his study of alchemical texts and symbols, Jung developed a rich and nuanced understanding of the psyche as a living, dynamic system, one that is constantly evolving towards greater wholeness and complexity. He saw the alchemical process as a kind of inner yoga, a way of engaging with the depths of the unconscious in order to catalyze profound changes in consciousness and behavior (Jung, 1944/1968).

At the same time, Jung was careful not to reduce alchemy or other spiritual traditions to mere psychological allegories. He recognized that these traditions contained their own unique wisdom and power, and that engaging with them required a stance of humility, openness, and respect. For Jung, the task was not to explain away the mysteries of the psyche, but rather to enter into a living dialogue with them, allowing their numinous power to transform and enlarge the conscious personality (Jung, 1961).

In this sense, Jung’s approach to psychology was deeply informed by his own spiritual journey, which took him from the intellectual world of Freudian psychoanalysis to the mystical depths of alchemy and beyond. By integrating the insights of these diverse traditions into his clinical work and personal life, Jung developed a profound and original vision of the human psyche, one that continues to inspire and challenge us today.

-

The Path of Individuation: A Journey Toward Wholeness

At the heart of Jung’s psychology is the concept of individuation – the lifelong process of psychological and spiritual development that leads to the realization of one’s unique wholeness and authenticity. While the details of this process can vary widely from person to person, Jung identified several key stages and themes that are common to the individuation journey (Jung, 1921/1976).

The first stage of individuation often involves a confrontation with the persona – the social mask or role that one presents to the world. As one becomes more aware of the limitations and inauthenticity of the persona, there may be a crisis of identity, a sense of disorientation and loss of meaning. This can be a painful and challenging time, but it is also an opportunity for growth and self-discovery (Jung, 1928/1966).

As the individuation process unfolds, one may encounter the shadow – the repressed or rejected aspects of the personality that are often experienced as negative, shameful, or threatening. Confronting the shadow requires a great deal of courage and honesty, as well as a willingness to take responsibility for one’s own darkness and imperfections. By integrating the shadow, one can reclaim the lost or disowned parts of the self and achieve a greater sense of wholeness and vitality (Jung, 1951/1959).

Another key stage of individuation involves the integration of the anima and animus – the contrasexual aspects of the psyche that represent the inner feminine within the male and the inner masculine within the female. By developing a conscious relationship with these archetypes, one can achieve a greater balance and wholeness within the personality, as well as more authentic and fulfilling relationships with others (Jung, 1936/1959).

As the journey continues, one may encounter other archetypal figures and forces, such as the wise old man/woman, the divine child, and the Self. Each of these encounters represents an opportunity for growth and transformation, as well as a challenge to the ego’s limited sense of identity and control (Jung, 1944/1953).

Ultimately, the goal of individuation is to establish a dynamic, ongoing relationship between the ego and the Self, in which the conscious personality becomes a vehicle for the realization of one’s deepest potential. This requires a willingness to embrace the unknown, to tolerate ambiguity and paradox, and to remain open to the guidance of the unconscious (Jung, 1921/1976).

For Jung, the individuation process is not a linear or predictable journey, but rather a spiraling, iterative process of self-discovery and self-creation, marked by periods of crisis, growth, and transformation. It is a journey that requires great patience, perseverance, and trust in the wisdom of the psyche, as well as a commitment to living with integrity and authenticity (Jung, 1961).

At the same time, Jung recognized that individuation is not a solitary quest, but one that is deeply connected to the larger web of life. As individuals strive to realize their unique wholeness, they contribute to the evolution of the species as a whole, helping to birth a new level of consciousness and a more integrated, compassionate world (Jung, 1916/1966).

In this sense, the path of individuation is a sacred calling, a way of aligning oneself with the deeper currents of life and participating in the great work of cosmic evolution. It is a journey that demands everything

-

Navigating the Spiritual Journey: Discernment and Mental Health

As interest in spirituality and personal growth has surged in recent decades, many individuals have turned to various practices and traditions in search of meaning, healing, and transformation. While the spiritual journey can be a powerful catalyst for positive change, it can also be fraught with challenges and pitfalls, particularly when it comes to mental health and well-being.

a) The Ego and the Unconscious: A Delicate Balance

One of the key dangers of the spiritual path is the potential for ego inflation – a state in which the ego becomes identified with archetypal or spiritual energies, leading to grandiosity, narcissism, and a loss of grounding in reality. This can happen when individuals engage in spiritual practices without adequate preparation or support, or when they use spirituality as a way to bypass or avoid the challenges of daily life (Welwood, 2000).

From a Jungian perspective, ego inflation occurs when the ego is overwhelmed by the contents of the unconscious, particularly the archetypal energies of the Self. While the Self represents the source of our deepest potential and creativity, it can also be experienced as a threatening or destructive force, particularly when the ego is not strong enough to withstand its power (Jung, 1944/1953).

To navigate the spiritual journey safely and effectively, it is essential to cultivate a healthy and balanced relationship between the ego and the unconscious. This requires a willingness to confront and integrate the shadow aspects of the psyche, as well as a commitment to grounding spiritual experiences in the realities of everyday life (Moore, 1992).

b) The Dangers of Ego Inflation and Spiritual Bypassing

When the ego becomes inflated, it can lead to a range of problematic behaviors and attitudes, from self-aggrandizement and entitlement to exploitation and abuse of power. This is particularly true in spiritual contexts, where leaders and teachers may use their authority to manipulate or control their followers, often under the guise of enlightenment or liberation (Kornfield, 1993).

Another common pitfall of the spiritual path is spiritual bypassing – the use of spiritual practices or beliefs to avoid or suppress difficult emotions, unresolved traumas, or developmental challenges. This can take many forms, from excessive detachment and dissociation to self-righteousness and spiritual materialism (Masters, 2010).

From a Jungian perspective, spiritual bypassing is a form of repression, in which the ego uses spirituality as a way to avoid confronting the shadow and integrating the unconscious. While this may provide temporary relief or a sense of superiority, it ultimately leads to a fragmented and inauthentic sense of self, as well as a disconnection from the deeper wisdom of the psyche (Jung, 1928/1966).

c) Discerning Between Spiritual Experiences and Mental Illness

Another challenge of the spiritual journey is the difficulty of distinguishing between genuine spiritual experiences and symptoms of mental illness. Many of the experiences that are valued in spiritual contexts, such as altered states of consciousness, visions, and encounters with non-ordinary realities, can also be indicators of serious mental health conditions, such as psychosis, mania, or dissociation (Grof & Grof, 1989).

From a Jungian perspective, the key to discerning between spiritual experiences and mental illness lies in the relationship between the ego and the unconscious. In genuine spiritual experiences, the ego is able to maintain a degree of awareness and control, even as it is expanded or transformed by the contents of the unconscious. In contrast, in cases of mental illness, the ego is overwhelmed or fragmented by the unconscious, leading to a loss of grounding in reality (Jung, 1939/1958).

To navigate this delicate terrain, it is essential to approach spiritual experiences with discernment, humility, and a willingness to seek guidance and support from qualified teachers and mental health professionals. It is also important to cultivate a strong and resilient ego, one that is able to withstand the challenges of the unconscious without losing its fundamental sense of self (Jung, 1944/1953).

d) The Role of Guidance and Tradition

One of the most important factors in navigating the spiritual journey safely and effectively is the presence of skilled and trustworthy guidance. Throughout history, spiritual traditions have emphasized the importance of working with a qualified teacher or mentor, someone who has undergone their own journey of transformation and can provide wisdom, support, and accountability along the way (Dass & Gorman, 1985).

From a Jungian perspective, the role of the teacher is not to provide answers or to impose a particular worldview, but rather to create a safe and supportive container in which the individual can engage with the unconscious and discover their own unique path of individuation. This requires a deep respect for the autonomy and creativity of the psyche, as well as a willingness to confront one’s own shadow and limitations as a teacher (Jung, 1961).

At the same time, Jung recognized the importance of grounding spiritual practice in the wisdom of established traditions, rather than relying solely on individual experience or intuition. By studying the symbols, myths, and practices of various spiritual traditions, individuals can gain a deeper understanding of the archetypal patterns and energies that shape the human psyche, as well as a sense of connection to a larger community of seekers (Jung, 1944/1968).

Ultimately, the path of spiritual growth and transformation is a deeply personal and individual journey, one that requires courage, discernment, and a willingness to embrace the unknown. By cultivating a strong and balanced ego, seeking guidance and support from qualified teachers and traditions, and approaching the unconscious with respect and humility, individuals can navigate the challenges and opportunities of the spiritual path with greater wisdom, compassion, and resilience.

-

Integrating Psychology and Spirituality: Jung’s Vision of a Third Way

One of Jung’s most significant contributions to the field of psychology was his attempt to bridge the gap between science and spirituality, to create a “third way” that honored both the empirical realities of the psyche and the numinous dimensions of human experience (Jung, 1961).

In contrast to the prevailing views of his time, which saw psychology as a purely secular and objective discipline, Jung recognized the essential role that spirituality played in the lives of his patients, as well as in his own personal journey of individuation. He saw that the spiritual impulse was a fundamental aspect of the human psyche, one that could not be reduced to mere wishful thinking or pathology (Jung, 1938/1966).

At the same time, Jung was critical of traditional religious institutions and dogmas, which he saw as often repressive and limiting of individual growth and creativity. He believed that a new kind of spirituality was needed, one that was grounded in the direct experience of the psyche and the natural world, rather than in external authorities or belief systems (Jung, 1944/1968).

For Jung, the key to integrating psychology and spirituality lay in the concept of the Self – the archetype of wholeness and the guiding principle of the individuation process. The Self represented the divine within, the source of our deepest potential and creativity, as well as our connection to the larger web of life (Jung, 1944/1953).

By engaging with the Self through practices such as dream analysis, active imagination, and symbol work, individuals could tap into the wisdom and energy of the unconscious, and begin to align their lives with their deepest values and aspirations. This process was not about achieving a static state of perfection, but rather about cultivating a dynamic, ongoing relationship between the ego and the Self, in which the conscious personality becomes a vehicle for the realization of one’s unique purpose and potential (Jung, 1921/1976).

At the same time, Jung recognized that the path of individuation was not a solitary or self-centered quest, but one that was deeply connected to the larger community of life. He saw that as individuals strived to realize their own wholeness, they also contributed to the evolution of the species as a whole, helping to birth a new level of consciousness and a more integrated, compassionate world (Jung, 1916/1966).

In this sense, Jung’s vision of a third way between psychology and spirituality was not just a personal or therapeutic endeavor, but a collective and evolutionary one. By honoring the spiritual dimensions of the psyche and working to integrate them with the insights of modern psychology, individuals could not only heal themselves, but also contribute to the healing of the world (Jung, 1961).

Today, Jung’s legacy continues to inspire and inform a wide range of psychological and spiritual practices, from depth psychology and transpersonal psychology to eco-psychology and embodied spirituality. By embracing the wisdom of the unconscious and the numinous dimensions of human experience, these approaches seek to create a more holistic and integrative framework for understanding the psyche and the cosmos, one that honors both the scientific and the sacred aspects of reality.

At the same time, Jung’s vision of a third way remains a challenging and elusive goal, one that requires ongoing exploration, experimentation, and dialogue. As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, with its ever-accelerating pace of change and its increasing sense of disconnection and fragmentation, the need for a more integrated and holistic approach to psychology and spirituality has never been greater.

By continuing to engage with the depths of the psyche and the mysteries of the unconscious, and by working to create communities of support and practice that can sustain us on the journey of individuation, we can carry forward Jung’s legacy and contribute to the ongoing evolution of human consciousness and culture. May we have the courage and the wisdom to walk this path with open hearts and minds, and to trust in the guidance of the Self as we navigate the challenges and opportunities of our time.

-

Soul and Earth: The Interconnection of Psyche and Place

Another key theme in Jung’s work is the recognition of the deep interconnection between the human psyche and the natural world. For Jung, the psyche was not just an individual or personal phenomenon, but a manifestation of the larger web of life, the anima mundi or world soul that animates and underlies all of creation (Jung, 1955/1960).

a) The Anima Mundi: Rediscovering the World Soul

The concept of the anima mundi has roots in ancient Greek philosophy and medieval alchemy, where it referred to the idea of a living, intelligent universe, imbued with soul and consciousness. For Jung, this idea was not just a metaphysical or poetic notion, but a psychological reality, one that had profound implications for our understanding of the psyche and its relationship to the world (Jung, 1955/1960).

Jung saw that the modern worldview, with its emphasis on materialism, individualism, and the separation of mind and matter, had led to a profound sense of alienation and disconnection from the natural world. By reducing nature to a collection of inanimate objects and resources to be exploited, humanity had lost touch with the living, ensouled dimensions of reality, and with our own deepest nature as part of the web of life (Jung, 1964/1970).

To heal this split and reconnect with the anima mundi, Jung believed that we needed to cultivate a new kind of relationship with the natural world, one that honored its sacredness, beauty, and intelligence. This required a shift in consciousness, a willingness to see beyond the surface appearances of things and to engage with the deeper, archetypal dimensions of reality (Jung, 1955/1960).

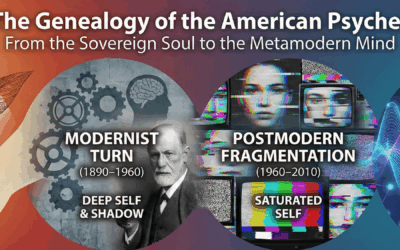

b) Stages of Consciousness: From Mythological to Post-Secular Awareness

Jung saw that throughout history, humanity had gone through different stages of consciousness in its relationship to the natural world. In the earliest, mythological stage, the world was experienced as alive and ensouled, populated by gods, spirits, and other non-human intelligences. In this worldview, there was no sharp distinction between the human and the more-than-human realms, and individuals lived in a state of participatory consciousness with the natural world (Jung, 1964/1970).

With the rise of modern science and the Enlightenment, however, this mythological worldview was largely replaced by a more secular and materialistic one, which saw nature as a collection of inanimate objects and resources to be studied and exploited. In this stage, the human mind was elevated as the sole source of meaning and value, and the natural world was stripped of its sacred and ensouled dimensions (Jung, 1964/1970).

For Jung, the challenge of our time is to move beyond this secular, disenchanted worldview and to cultivate a new kind of post-secular awareness, one that integrates the insights of modern science with the wisdom of the world’s spiritual traditions. This requires a willingness to re-engage with the mythological and archetypal dimensions of reality, not as a regression to pre-modern superstition, but as a way of enriching and deepening our understanding of the psyche and the cosmos (Jung, 1944/1968).

c) The Chthonic Dimension of the Psyche

One of the key aspects of this post-secular awareness is the recognition of the chthonic dimension of the psyche – the deep, earthy, and instinctual layers of the unconscious that connect us to the living world. For Jung, the chthonic realm was the source of our deepest creativity, vitality, and wisdom, as well as our capacity for regeneration and renewal (Jung, 1955/1960).

Unfortunately, in the modern world, the chthonic dimension of the psyche has been largely repressed and devalued, seen as primitive, irrational, or even demonic. This has led to a profound split between the human and the more-than-human realms, and to a sense of alienation and disconnection from our own deepest nature (Jung, 1964/1970).

To heal this split and reconnect with the chthonic realm, Jung believed that we needed to cultivate a new kind of relationship with the unconscious, one that honored its wisdom, power, and creativity. This required a willingness to confront our own shadow, to engage with the dark and difficult aspects of the psyche, and to trust in the regenerative power of the unconscious (Jung, 1955/1960).

d) Implications for Ecological Awareness and Spiritual Practice

Jung’s insights into the interconnection of psyche and place have profound implications for our understanding of ecological awareness and spiritual practice. By recognizing the sacredness and intelligence of the natural world, and by cultivating a more participatory and embodied relationship with the Earth, we can begin to heal the split between mind and matter, and to find a new sense of meaning and purpose in our lives.

This requires a willingness to engage with the mythological and archetypal dimensions of our experience, to see the world as alive and ensouled, and to cultivate a sense of reverence and respect for the more-than-human realms. It also requires a commitment to confronting the shadow aspects of our own psyche, and to working through the difficult emotions and traumas that keep us disconnected from our own deepest nature.

In practical terms, this might involve practices such as spending time in nature, engaging in ecological restoration and conservation work, studying indigenous wisdom traditions, and cultivating a more embodied and sensory relationship with the world around us. It might also involve using tools such as dream work, active imagination, and ritual to explore the deeper, archetypal dimensions of our experience and to connect with the anima mundi.

Ultimately, the goal of this work is not just to heal our own individual psyches, but to contribute to the healing of the Earth as a whole. By reconnecting with the living, ensouled dimensions of reality, and by working to create a more sustainable and regenerative relationship with the natural world, we can help to midwife a new era of human consciousness and culture, one that honors the sacredness and intelligence of all life, and that recognizes our deep interconnection with the web of creation.

-

Engaging Diverse Jungian Voices: Contemporary Perspectives and Applications

Since Jung’s death in 1961, his ideas have continued to evolve and inspire a wide range of thinkers, practitioners, and activists around the world. Today, Jungian psychology is a diverse and dynamic field, with a growing recognition of the need to engage with issues of social justice, cultural diversity, and ecological sustainability.

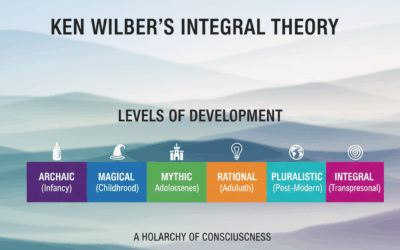

One of the key developments in contemporary Jungian thought has been the emergence of post-Jungian perspectives, which seek to critique and expand upon Jung’s original ideas in light of new insights from fields such as neuroscience, complexity theory, and postmodern philosophy. These approaches challenge some of the more essentialist and universalizing aspects of Jung’s thought, and emphasize the need for a more contextual and culturally-sensitive understanding of the psyche (Samuels, 1985).

Another important trend has been the growth of Jungian applications in fields such as education, organizational development, and social activism. By applying Jungian concepts such as the shadow, the collective unconscious, and the archetype of the Self to issues of power, privilege, and oppression, these approaches seek to create more just and equitable communities and institutions (Cox & Lyddon, 1997).

At the same time, there has been a growing recognition of the need to engage with the voices and perspectives of historically marginalized groups within the Jungian community. This includes a greater emphasis on the contributions of women, people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and indigenous peoples, as well as a more critical examination of Jung’s own cultural biases and blind spots (Adams et al., 2015).

One example of this is the work of postcolonial and decolonial scholars, who have challenged the Western and Eurocentric assumptions that underlie much of Jungian theory and practice. By engaging with the wisdom traditions and liberation struggles of the Global South, these approaches seek to create a more inclusive and culturally-responsive form of depth psychology, one that honors the diversity and resilience of the human spirit (Duran, 2006).

Another example is the growing field of eco-psychology, which draws upon Jungian concepts such as the anima mundi and the chthonic dimension of the psyche to explore the deep interconnection between human well-being and ecological sustainability. By recognizing the sacredness and intelligence of the more-than human world, these approaches seek to create a more holistic and regenerative vision of mental health and spiritual growth, one that includes a commitment to social and environmental justice (Rust & Totton, 2012).

Finally, there has been a growing interest in the applications of Jungian psychology to issues of spirituality and religion. While Jung himself was often critical of traditional religious institutions and dogmas, he recognized the essential role that spirituality played in the process of individuation and the quest for meaning and purpose in life (Jung, 1938/1966).

Today, many Jungian thinkers and practitioners are exploring the ways in which depth psychology can inform and enrich our understanding of spiritual experience and practice. This includes a greater emphasis on the embodied and relational dimensions of spirituality, as well as a more critical examination of the power dynamics and cultural biases that can shape religious institutions and beliefs (Stein, 2020).

The Competing Schools of Post-Jungian Thought

Since Jung’s death in 1961, his legacy has been carried forward by a diverse array of scholars, analysts, and practitioners, each offering their own unique perspective on the theory and practice of depth psychology. These post-Jungian thinkers have sought to build upon, critique, and expand Jung’s original ideas, leading to a rich and dynamic landscape of competing schools and movements. In this section, we will explore some of the most influential of these post-Jungian perspectives, and consider how they have shaped the ongoing evolution of Jungian thought.

Classical Jungian Psychology

One of the earliest and most prominent schools to emerge in the wake of Jung’s death was classical Jungian psychology, which sought to preserve and promote Jung’s original teachings in their purest form. Led by figures such as [~Marie-Louise von Franz~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-archetypal-psychology-of-marie-louise-von-franz/), [~Barbara Hannah~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/barbara-hannah-jungian-analyst-teacher-and-biographer/), and [~Jolande Jacobi~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-archetypal-psychology-of-jolande-jacobi-exploring-the-realms-of-the-unconscious/), the classical Jungians emphasized the importance of the [~archetypes~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/how-to-understand-jung-part-2-applying-jungian-archetypes/), the collective unconscious, and the individuation process, and tended to be more skeptical of efforts to integrate Jungian ideas with other philosophical or psychological traditions (Samuels, 1985).

For the classical Jungians, the goal of analysis was to facilitate the individual’s encounter with the unconscious and to support the natural unfolding of the individuation process. They placed great emphasis on the interpretation of dreams, fantasies, and other symbolic material, and on the development of a strong and authentic ego that could withstand the challenges of the unconscious. The classical Jungians also tended to be more interested in the spiritual and transpersonal dimensions of the psyche, and in the role of mythology, religion, and the arts in shaping human experience (Stein, 1998).

Archetypal Psychology

In the 1970s, a new school of post-Jungian thought emerged in the form of archetypal psychology, founded by [~James Hillman~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-archetypal-psychology-of-james-hillman-re-visioning-the-foundations-of-mind-and-culture/). Hillman was a student of Jung’s and had worked closely with von Franz and other classical Jungians, but he became increasingly critical of what he saw as the limitations and biases of the classical approach. For Hillman, the goal of psychology was not to support the ego’s heroic journey of individuation, but rather to cultivate a deeper relationship with the soul and the imaginal realm (Hillman, 1975).

Archetypal psychology emphasized the importance of the archetypes as autonomous and universal patterns that shape human experience, but it rejected the idea of the collective unconscious as a literal or metaphysical entity. Instead, Hillman argued that the archetypes were best understood as fundamental structures of the imagination, and that the goal of psychology was to engage with these structures creatively and poetically. He also placed great emphasis on the role of myth, literature, and the arts in shaping the psyche, and on the importance of cultivating a polytheistic and animistic worldview that honored the diversity and complexity of the soul (Hillman, 1989).

Developmental Psychology

Another significant school of post-Jungian thought to emerge in the later 20th century was developmental psychology, which sought to integrate Jungian ideas with insights from psychoanalysis, attachment theory, and cognitive psychology. Led by figures such as [~Michael Fordham~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/michael-fordham-integrating-developmental-psychology-with-analytical-psychology/) and [~Erich Neumann~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-archetypal-psychology-of-erich-neumann-exploring-the-origins-and-development-of-consciousness/), the developmental Jungians emphasized the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping the psyche, and argued that the archetypes and the individuation process needed to be understood in the context of human development (Samuels, 1985).

For the developmental Jungians, the goal of analysis was not only to facilitate the individual’s encounter with the unconscious, but also to help them to work through and integrate early experiences of trauma, neglect, or attachment disruption. They placed great emphasis on the role of the therapeutic relationship in supporting this process, and on the importance of attending to the transferential and countertransferential dynamics between analyst and analysand. The developmental Jungians also tended to be more interested in the practical applications of Jungian ideas in fields such as child psychology, education, and social work (Astor, 1995).

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and the Beebe Model

In addition to these major schools, post-Jungian thought has also been influenced by efforts to apply Jungian concepts to personality theory and assessment. One of the most well-known examples of this is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), developed by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers. The MBTI is based on Jung’s theory of psychological types, which proposes that individuals have innate preferences for certain attitudes (introversion vs. extraversion), functions (thinking, feeling, sensation, intuition), and lifestyle orientations (judging vs. perceiving) (Myers & Myers, 1980).

Another influential model in this vein is the Beebe model, developed by Jungian analyst [~John Beebe~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/unlocking-personality-and-worldview-with-the-beebe-model/). The Beebe model expands on Jung’s typology by proposing that each individual has a unique “cast of characters” within their psyche, corresponding to the eight function-attitudes described by Jung. According to Beebe, these inner figures play archetypal roles such as the hero, the parent, the child, and the trickster, and understanding their interplay can provide valuable insights into an individual’s personality and psychological development (Beebe, 2004).

Somatic and Experiential Approaches

Another important trend in post-Jungian thought has been the integration of Jungian concepts with somatic and experiential approaches drawn from Eastern spiritual practices and Western body-oriented therapies. Pioneers in this area include [~Arnold Mindell~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/arnold-mindell-and-process-oriented-psychology-pioneering-a-path-beyond-jungian-analysis/), founder of process-oriented psychology, and [~Sidra~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-psychology-of-selves-the-pioneering-work-of-hal-and-sidra-stone/) and [~Hal Stone~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-psychology-of-selves-the-pioneering-work-of-hal-and-sidra-stone/), creators of Voice Dialogue and the Psychology of Selves.

Mindell’s process-oriented psychology incorporates elements of Taoism, shamanism, and physics to explore how the unconscious communicates through bodily experiences, symptoms, and group dynamics. Stone and Stone’s Voice Dialogue method uses active imagination techniques to help individuals access and integrate the various subpersonalities or “selves” within their psyche. Other post-Jungians, such as [~Nathan Schwartz-Salant~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/nathan-schwartz-salant-illuminating-the-depths-of-the-psyche/), have drawn on concepts from alchemy and Kabbalah to develop experiential approaches that work with the body, subtle energies, and non-ordinary states of consciousness.

These somatic and experiential approaches reflect a growing recognition of the importance of embodiment, energy, and altered states in depth psychology, and a desire to develop methods that can directly access and transform the deeper layers of the psyche. They also represent a movement towards greater integration of Jungian psychology with the wisdom traditions of the East and the indigenous practices of shamanic cultures.

Archetypal Astrology

Archetypal astrology is a perspective that combines Jungian psychology with the ancient practice of astrology. Developed by thinkers such as [~Richard Tarnas~](https://www.cosmosandpsyche.com/About_Richard_Tarnas.php) and [~Stanislav Grof~](https://grof-holotropic-breathwork.net/about-stanislav-grof/), this approach sees the planets and other celestial bodies as symbolic representations of archetypal forces that shape human experience (Tarnas, 2006).

For archetypal astrologers, the birth chart is a map of the individual psyche, revealing the unique configuration of archetypal energies that inform a person’s personality, challenges, and potentials. By studying the movements and alignments of the planets, archetypal astrologers seek to gain insight into the larger patterns and cycles that shape both individual and collective experience (Grof, 2009).

Jungian Ecopsychology

Jungian ecopsychology is a perspective that explores the relationship between the human psyche and the natural world, drawing on Jung’s concepts of the collective unconscious, archetypes, and the Self. Developed by thinkers such as [~Theodore Roszak~](https://www.britannica.com/biography/Theodore-Roszak) and [~Mary-Jayne Rust~](https://www.mjrust.net/), this approach sees the ecological crisis as a symptom of a deeper psycho-spiritual imbalance, rooted in the modern Western worldview that sees humans as separate from and superior to nature (Roszak, 1992).

For Jungian ecopsychologists, the task of individuation is not just a personal journey of self-discovery, but a process of reconnecting with the larger web of life and developing a more reciprocal and participatory relationship with the natural world. They argue that by cultivating a deeper sense of our ecological Self, we can begin to heal the split between psyche and nature, and contribute to the creation of a more sustainable and regenerative culture (Rust, 2008).

Jungian Feminist Psychology

Jungian feminist psychology is a perspective that seeks to integrate the insights of feminist theory and gender studies with Jungian concepts and methods. Developed by thinkers such as [~Jean Shinoda Bolen~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/?p=5786&preview=true), [~Naomi Goldenberg~](https://carleton.ca/religion/people/naomi-goldenberg/), and [~Polly Young-Eisendrath~](https://young-eisendrath.com/about/), this approach critiques the patriarchal and androcentric biases in Jung’s original work, while also recognizing the liberatory and transformative potential of depth psychology for women’s lives (Bolen, 1984).

Jungian feminist psychologists have sought to reclaim and revalue the feminine aspects of the psyche that have been marginalized or pathologized in traditional Jungian theory, such as the anima, the mother archetype, and the goddess. They have also explored the ways that gender roles, power dynamics, and social oppression shape the process of individuation and the experience of the Self (Young-Eisendrath, 2012).

Jungian Arts-Based Therapy

Jungian arts-based therapy is a perspective that integrates Jungian concepts and methods with various forms of creative expression, such as painting, sculpture, music, dance, and poetry. Developed by thinkers such as [~Shaun McNiff~](https://www.lesley.edu/faculty/shaun-mcniff) and [~Joan Chodorow~](https://beyondthecouch.org/1356/every-moment-in-a-jungian-analysis-counts-an-interview-with-jungian-analyst-joan-chodorow), this approach sees the arts as a powerful means of accessing and expressing the depths of the psyche, and of facilitating the process of individuation and healing (McNiff, 1981).

For Jungian arts-based therapists, the creative process itself is a form of active imagination, a way of dialoguing with the unconscious and bringing its contents into conscious awareness. They argue that by engaging with the symbolic and metaphorical language of the arts, individuals can bypass the censorship of the ego and tap into the deeper layers of the psyche, where transformation and renewal can occur (Chodorow, 1997).

Jungian-Oriented Spiritual Psychology

Finally, there has been a growing interest in recent years in the intersection of Jungian psychology and spirituality, leading to the development of various forms of Jungian-oriented spiritual psychology. These approaches seek to integrate Jungian concepts with insights from contemplative traditions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and mystical Christianity (Schlamm, 2022).

One of the key figures in this movement is [~Thomas Moore~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/thomas-moore-a-compelling-vision-for-the-soul/), a former monk and psychotherapist who has written extensively on the relationship between psychology and spirituality. Moore’s approach, which he calls “care of the soul,” emphasizes the importance of cultivating a deep and soulful relationship with the mysteries of life, and of honoring the spiritual dimensions of the psyche (Moore, 1992).

Other Jungian-oriented spiritual psychologists, such as [~Lionel Corbett~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/lionel-corbett-exploring-the-psyche-spirituality-and-the-sacred/) and [~Murray Stein~](https://gettherapybirmingham.com/murray-stein-bridging-jungian-psychology-and-contemporary-thought/), have focused on the ways that Jungian concepts such as the Self, the archetypes, and synchronicity can be understood in the context of spiritual experience and practice. They have also explored the role of Jungian psychology in supporting the process of spiritual transformation and awakening (Corbett, 2007; Stein, 2022).

The post-Jungian landscape continues to evolve and diversify, as new generations of scholars and practitioners seek to adapt Jung’s insights to the needs and challenges of the contemporary world. While the schools and movements described above represent some of the most significant and enduring trends, there are many other innovative thinkers and approaches that are shaping the future of Jungian thought. As the field continues to grow and change, it will be essential for post-Jungians to remain open to new perspectives and possibilities, while also staying grounded in the core principles and values that have guided depth psychology from its inception.

-

Conclusion: Individuation in an Age of Upheaval

As we navigate the complex and turbulent waters of the 21st century, the relevance and urgency of Jung’s ideas has never been greater. With the accelerating pace of technological change, the growing threat of ecological collapse, and the deepening polarization and fragmentation of our social and political institutions, the need for a more integrated and holistic approach to psychology and spirituality is more pressing than ever.

At the heart of Jung’s vision is the concept of individuation – the lifelong process of psychological and spiritual development that leads to the realization of our deepest potential and the integration of the conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche. While the path of individuation is ultimately a personal and individual one, it is also deeply connected to the larger web of life and the collective challenges and opportunities of our time (Jung, 1921/1976).

As we strive to navigate the complexities of the modern world, the tools and insights of Jungian psychology can offer a valuable compass and guide. By cultivating a deeper relationship with the unconscious, engaging with the mythological and archetypal dimensions of our experience, and working to integrate the shadow aspects of our psyche, we can begin to heal the splits and divisions that keep us fragmented and disconnected from our own deepest nature and from the world around us.

At the same time, the path of individuation is not a solitary or self-centered quest, but one that is fundamentally connected to the larger community of life. As we work to realize our own unique potential and purpose, we are also called to contribute to the healing and transformation of the world, to create a more just, sustainable, and compassionate future for all beings.

This requires a willingness to engage with the difficult and sometimes painful realities of our time, to confront the ways in which we are complicit in systems of oppression and exploitation, and to work towards a more equitable and regenerative way of being in the world. It also requires a commitment to cultivating a more embodied and relational spirituality, one that honors the sacredness and intelligence of the natural world and recognizes our deep interconnection with the web of life.

Ultimately, the goal of individuation is not just to achieve a state of personal fulfillment or enlightenment, but to become a vessel for the creative and transformative energies of the universe, to align our lives with the deeper purpose and meaning of existence. As Jung himself wrote:

“The goal of psychological, as of biological, development is self-realization, or individuation. But since man knows himself only as an ego, and the self, as a totality, is indescribable and indistinguishable from a God-image, self-realization – to put it in religious or metaphysical terms – amounts to God’s incarnation. That is already expressed in the fact that Christ is the son of God. And because individuation is an heroic and often tragic task, the most difficult of all, it involves suffering, a passion of the ego: the ordinary empirical man we once were is burdened with the fate of losing himself in a greater dimension and being robbed of his fancied freedom of will. He suffers, so to speak, from the violence done to him by the self.” (Jung, 1961, p. 354)

As we embark on this heroic and often tragic task, let us remember that we are not alone, but part of a larger community of seekers and healers, all working towards the realization of a more whole and integrated world. May we have the courage and the compassion to walk this path with open hearts and minds, to trust in the wisdom of the psyche and the guidance of the Self, and to contribute our own unique gifts and talents to the great work of individuation and transformation that lies before us

Read More on Jung here:

-

References

Adams, G., Dobles, I., Gómez, L. H., Kurtiş, T., & Molina, L. E. (2015). Decolonizing psychological science: Introduction to the special thematic section. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 213-238.

Cox, D., & Lyddon, W. J. (1997). Constructivist conceptions of self: A discussion of emerging identity constructs. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 10(3), 201-219.

Dass, R., & Gorman, P. (1985). How can I help? Stories and reflections on service. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Duran, E. (2006). Healing the soul wound: Counseling with American Indians and other native peoples. New York: Teachers College Press.

Grof, S., & Grof, C. (1989). Spiritual emergency: When personal transformation becomes a crisis. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher.

Jung, C. G. (1916/1966). The structure and dynamics of the psyche. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 8). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1921/1976). Psychological types. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 6). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1928/1960). On psychic energy. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 8). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1934/1950). A study in the process of individuation. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 9i). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1936/1959). The concept of the collective unconscious. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 9i). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1938/1966). Psychology and religion. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 11). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1939/1958). Conscious, unconscious, and individuation. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 9i). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1944/1953). Psychology and alchemy. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 12). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1944/1968). Psychology and alchemy. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 12). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1951/1959). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 9ii). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1955/1960). Synchronicity: An acausal connecting principle. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 8). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1961). Memories, dreams, reflections. New York: Vintage Books.

Jung, C. G. (1964/1970). Civilization in transition. In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; Vol. 10). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kornfield, J. (1993). A path with heart: A guide through the perils and promises of spiritual life. New York: Bantam Books.

Masters, R. A. (2010). Spiritual bypassing: When spirituality disconnects us from what really matters. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the soul: A guide for cultivating depth and sacredness in everyday life. New York: HarperCollins.

Rust, M.-J., & Totton, N. (Eds.). (2012). Vital signs: Psychological responses to ecological crisis. London: Karnac Books.

Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the post-Jungians. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Stein, M. (Ed.). (2020). Jungian psychoanalysis: Working in the spirit of Carl Jung. Chicago: Open Court.

Welwood, J. (2000). Toward a psychology of awakening: Buddhism, psychotherapy, and the path of personal and spiritual transformation. Boston: Shambhala.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

0 Comments