Who was Robert Bly?

“If a culture does not deal with the warrior energy—take it consciously, discipline it, honor it—it will turn up outside in the form of street gangs, wife beating, drug violence, brutality to children, and aimless murder.”

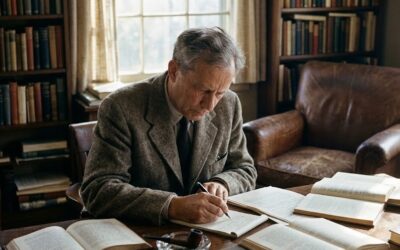

Robert Bly (1926-2021) was an influential American poet, author, activist, and leader of the mythopoetic men’s movement. Over his long career, Bly published numerous collections of poetry, translations, and prose works that explored masculinity, spirituality, and the human condition. He is best known for his 1990 bestseller Iron John: A Book About Men, which used the Grimms’ fairy tale to articulate a vision of mature masculinity and inspired a generation of men to gather in workshops, retreats, and drumming circles.

Bly’s work was deeply influenced by Jungian psychology, mythology, and indigenous wisdom traditions. He saw myths and folktales as profound expressions of the collective unconscious that could guide modern individuals on the path of psycho-spiritual development. By promoting a “deep masculine” path of inner work and initiation, Bly sought to heal the wounds of patriarchal culture and help men cultivate a more embodied, soulful, and relational way of being.

This essay explores Bly’s key ideas and contributions, focusing on his use of myth, group work, and ritual process to transform masculine identity. It examines his notion of the “deep masculine,” his appropriation of indigenous practices like drumming and sweat lodges, his facilitation of men’s groups, and his belief in the power of poetry and expressive arts. It also considers critical responses to his work from feminists, BIPOC voices, and others. Finally, it reflects on Bly’s legacy and enduring influence on contemporary men’s work and the wider culture.

Life and Career:

Robert Elwood Bly was born in 1926 in Madison, Minnesota. He attended Harvard University and received his M.A. from the University of Iowa in 1956. As a young man, he spent time in Norway as a Fulbright scholar translating Norwegian poetry.

Bly emerged as a major figure in American poetry in the 1950s. Influenced by Latin American surrealism and European experimentalism, he co-founded the influential literary magazine The Fifties (later The Sixties). His second collection, The Light Around the Body, won the National Book Award for Poetry in 1968.

In the 1970s, Bly gained widespread attention as an anti-war activist. He co-founded American Writers Against the Vietnam War and led much-publicized resistance to the draft. Around this time, he began exploring men’s issues and men’s work in the context of the feminist and gay liberation movements.

Bly’s interest in men’s work crystallized in the early 1980s when he began leading men’s conferences and workshops with mythologist Michael Meade and others. Drawing on poetry, mythology, fairy tales, and indigenous rituals, Bly and his colleagues sought to create transformative experiences of male initiation and bonding. These events attracted thousands of participants and established Bly as a leader in the growing men’s movement.

In 1990, Bly published Iron John: A Book About Men, which became an international bestseller and his most well-known work. Inspired by a set of initiation stories told to him by German psychoanalyst Erich Neumann, the book used the Grimms’ tale of “Iron John” to outline an archetypal path of male growth and healing.

Bly’s ideas generated significant interest as well as controversy. Some hailed him as a visionary voice calling men to a new era of relational, embodied masculinity. Others, including many feminists, criticized his allegedly essentialist views and appropriation of indigenous traditions.

In his later years, Bly continued to write poetry and prose, publishing over 30 works in total. He also led workshops and gatherings, solidifying his role as an elder in the “expressive men’s movement.” He was known for his dynamic performance style, Zen sense of humor, and tireless advocacy for soulful art and psychological growth.

Bly won numerous awards over his career including fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller foundations. He was also active in translating poets like Kabir, Hafez, Rilke and Machado, helping introduce their work to an American audience. Bly passed away at the age of 94 in 2021, leaving a profound imprint on American letters and the contemporary men’s movement.

Key Ideas and Themes:

Myth, Fairy Tales, and the Masculine Psyche:

Like Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell, Bly believed that myths and folktales contained profound truths about the structure of the psyche and the path of human development. He was especially drawn to myths of male initiation, which he felt revealed universal patterns of the masculine journey towards maturity.

Bly’s most famous work, Iron John, is a book-length interpretation of the Grimms’ tale of the same name. For Bly, the story depicts an archetypal pattern of male initiation that has been lost in modern culture. The wild man Iron John represents the “deep masculine” – the earthy, instinctual energies of manhood that are often repressed by socialization but crucial for mature male identity.

The story’s protagonist, a young prince, undertakes a series of physical and spiritual trials to free Iron John and integrate his energies. In the process, he develops the traits of an initiated adult male: embodied presence, assertiveness, vulnerability, a capacity for solitude, an openness to the feminine, the ability to bless others, and a grounding in deep masculine energy. This transformative journey, which involves a descent into darkness and symbolic death, activates the prince’s innate masculinity and gifts.

Bly saw this mythic pattern as a map for contemporary male healing and growth. Modern men, in his view, suffered from a disconnection from the “wild man” and the deep masculine qualities he represented. Trapped within a “Sibling Society” of extended adolescence and alienated from nature, many men remained in a perpetual “Boy Psychology,” lacking purpose, potency, and a secure male identity.

The way forward, Bly argued, was for men to undertake their own “male mysteries” through therapy, dreamwork, men’s gatherings, and encounters with male elders and mentors. By connecting with “Iron John energies” and the inner king, warrior, magician, and lover archetypes, men could develop a mature masculinity marked by strength, sensitivity, and soul.

Bly used many other myths, legends, and folktales as lenses for men’s inner work. He drew upon the Parsifal story to describe the male “Grail Quest,” the Grimms’ “The Devil’s Sooty Brother” to illustrate male depression, and fairy tales like “The White Bear King Valemon” to evoke the stages of masculine individuation. In each case, Bly approached the tale as a living reality, rich in psychological wisdom and guidance for the present.

Group Work and Ritual Process:

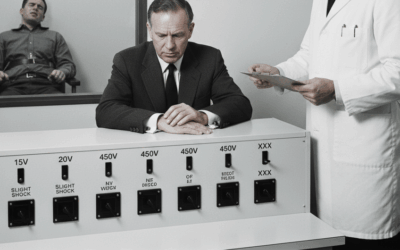

Alongside his use of myth, Bly was a major proponent of group work and ritual process as vehicles for male growth and initiation. Beginning in the 1980s, he led numerous men’s gatherings and “wild man weekends” that sought to create experiential containers for masculine healing and bonding.

These events often involved expressive arts, poetry sharing, improvisational movement, and group discussion to help men access and integrate their intuitive, emotional selves. Participants would explore sensitive topics like father wounds, sexuality, and purpose while receiving mirroring and support from other men. The goal was to create a safe space for men to remove their persona masks, grieve losses, claim strengths, and experience male community.

Bly was especially known for his use of ecstatic body practices like drumming, chanting, dancing, and even mud wrestling in his men’s groups. He felt these preverbal, kinaesthetic modalities could bypass men’s verbal defenses and connect them with deep masculine energies and altered states. Bly also believed that drumming and oral storytelling could produce a collective energy field or temenos that facilitated male bonding and generated a healing “group mind.”

Another key feature of Bly’s group work was his use of ritual process, often drawn from indigenous and shamanic traditions. He would sometimes lead sweat lodges, fasting ceremonies, grief rituals, and other rites of passage to mark important transitions and facilitate ego-death/rebirth experiences. Bly felt these rituals provided an essential initiatory container that was lacking in the modern West.

For Bly, men’s groups and rituals were not just therapeutic modalities but central to the “re-mythologization” of masculinity. He believed that by gathering to share stories, poetry, and soulful practices, men could begin to create a new culture of engaged, emotionally literate, and spiritually grounded manhood. This “secret garden of men” could then pollinate the wider society, fomenting cultural and political change.

The Deep Masculine and Male Individuation:

The core theme that animated Bly’s work was his vision of the “deep masculine” – a way of inhabiting manhood that was life-affirming, soul-oriented, and rooted in the body and Earth. Bly developed this notion in contrast to what he saw as the prevailing “toxic masculinity” of the modern West, which glorified aggression, domination, and conquest.

For Bly, the deep masculine represented an innate, embodied energy of maturity, presence, sensitivity, and spirituality. He associated it with the “Wild Man” archetype – an inner figure of instinctual wisdom and earthy vitality. The deep masculine was about living from one’s core, speaking authentically, embracing vulnerability, stewarding the natural world, and serving something beyond the ego.

At the same time, Bly emphasized that the deep masculine was not about rejecting traditional male virtues like strength, courage, and assertiveness, but grounding them in a wider spiritual context. He praised the “Masculine Yang” qualities of clarity, purpose, and decisive action, while also stressing the need for men to cultivate the “Masculine Yin” of intuition, receptivity, and relationship. Mature masculinity involved a dance between these two poles.

Cultivating the deep masculine, for Bly, was central to male individuation and the forging of a potent male identity. Drawing on Jungian ideas, he saw individuation as a lifelong journey of integrating the unconscious and becoming one’s fullest self. For men, this meant confronting mother/father complexes, making peace with the inner feminine (anima), befriending the shadow, and connecting with the deep Self.

Robert Bly’s Eight Stage Male Individuation:

In Iron John, Bly laid out an eight-stage model of the male individuation journey, drawing on the Grimms’ fairy tale of the same name. Each stage represents a key developmental task or encounter with archetypal energies that Bly saw as crucial for men’s psycho-spiritual growth.

The Pillow and Key:

Leaving the Mother’s World This stage involves separating from the maternal matrix and the comforts of boyhood. It requires leaving behind the “Pillow” of softness and dependence to embrace the hardness and independence of manhood. The “Key” represents the unlocking of one’s authentic masculine identity.

The Wild Man and Ashes:

Connecting with Deep Masculine Energy Here the male ego encounters the “Wild Man” – the earthy, instinctual energy of the deep masculine. This stage involves getting dirty, descending into the “Ashes” of one’s shadow material, and connecting with the primal vitality and wildness that lies beneath the persona.

The Road of Ashes, Descent, and Grief

This is the stage of the “Road of Trials,” where the male ego undergoes a series of challenges, ordeals, and losses. It involves a descent into the underworld of the psyche, a confrontation with mortality, and a grieving of the “Ashes” of boyhood. This painful initiation is necessary for the ego to be humbled and transformed.

The Hunger for the King in Fairy Tales, and in the Modern Male

In this stage, the male psyche yearns for the “King” – the archetype of mature masculine leadership, order, and blessing. This hunger for the “King energy,” Bly argues, is often projected onto outer figures like mentors, heroes, and celebrities. The task is to withdraw these projections and develop one’s own inner King.

The Meeting with the God-Woman

This stage involves an encounter with the “God-Woman” – the sacred, transformative power of the feminine. It requires opening to the mysteries of sexuality, creativity, and the anima (inner feminine). The male psyche must learn to embrace and integrate the “Goddess energies” to achieve wholeness.

To Bring the Interior Warriors into Balance

Here the task is to reconcile and harmonize the different “Warrior” archetypes within the male psyche. These include the Trickster, the Mythical Hero, the Spiritual Warrior, and the Warrior of Presence. Balancing these inner Warriors creates a flexible, resourceful masculinity that can respond adaptively to life’s challenges.

The Purse of Coins between the Masculine and Feminine

This stage involves the inner marriage of masculine and feminine energies. The “Purse of Coins” represents the sacred exchange and reciprocity between the King and Queen archetypes. It points to the need for men to honor the feminine within and without, and to develop a dynamic partnership between their inner masculine and feminine.

The Ecstasy of the Kingdom, the Male Naivete, and the Garden

That is Still There The final stage represents the fruition of the individuation journey. The “Ecstasy of the Kingdom” points to a sense of joy, vitality, and at-home-ness in the world that emerges when the deep masculine is integrated. The “Male Naivete” is the capacity to see the world with fresh, wonder-filled eyes, unclouded by cynicism or jadedness. And the “Garden That is Still There” is the primal, Edenic state of unalienated presence that awaits the fully individuated man.

Bly presents these eight stages not as a linear sequence but as an iterative, spiral-like process of deepening and integration. Each stage involves a crisis, a letting-go, and a regeneration, and each prepares the ground for the next. Taken together, they form an archetypal roadmap for the male journey towards wholeness, purpose, and mature masculine identity.

Each stage involved key developmental tasks and encounters with archetypal energies: separating from the Mother, discovering one’s mission, retrieving the Golden Ball, receiving the boon of the feminine, integrating the inner Warrior, etc. The goal was not to reject or transcend “ordinary masculinity” but to deepen, spiritualize and anchor it in service of Self and world. As Bly wrote:

“The aim is not to be the Wild Man, but to be in touch with the Wild Man…The Wild Man is not opposed to the King; he is the King’s right arm and necessary angel.”

Legacy and Influence:

Bly was one of the most prominent voices of the mythopoetic men’s movement of the 1980s-90s. His books, workshops, and charismatic presence inspired thousands of men to explore the Jungian unconscious and reconnect with deep masculine energies. In many ways, he served as elder and “ritual leader” for a generation of men seeking a new vision of manhood.

Bly’s great contribution was to link men’s healing and growth with the mythic imagination. By teaching men to engage myths and fairy tales as road maps for their inner work, he helped to “re-mythologize” masculinity and gave men an archetypal container for their spiritual longings. His model of male individuation provided a much-needed alternative to the prevailing images of manhood and inspired many men to undertake a deeper “soul journey.”

At the same time, Bly was a lightning rod for criticism and controversy. His allegedly essentialist views on gender and appropriation of indigenous practices like drumming and sweat lodges came under fire from feminist, anti-racist and Native American activists. Some accused him of misogyny, homophobia and promoting a narrowly white, middle-class view of masculinity.

Bly’s relationship to feminism was especially complex. While he supported women’s liberation and urged men to develop their inner feminine, some felt he reinforced gender binaries and stereotypes. His male-only focus and use of terms like “soft males” rubbed many the wrong way, even as he called for a “big enough” masculinity that could embrace traits like gentleness, compassion and vulnerability.

Despite these criticisms, Bly left an indelible mark on the contemporary men’s movement. His Jungian approach to men’s work, use of expressive arts, and focus on male initiation became a template for men’s gatherings around the world. Many of today’s men’s groups and wilderness programs carry on his legacy, even as they update his ideas for a new era.

More broadly, Bly’s notion of the “deep masculine” helped to expand cultural notions of healthy manhood. By championing a spiritually grounded masculinity rooted in embodiment, relatedness and soul, he pointed beyond the impoverished “Guy Code” and planted seeds for an integral male identity. As the crisis of masculinity continues to brew, Bly’s call to “retrieve the Wild Man” feels ever more relevant.

Reckoning with Bly’s legacy also means wrestling with the blind spots of the mythopoetic men’s movement. His work often presupposed a white, cisgender and heterosexual male subject, marginalizing the experiences of men of color and LGBTQ+ men. Critics argue that myth-based men’s work can risk essentializing gender, glamorizing tribalism, and sidestepping the institutional realities of power and privilege. An approach to male healing centered on self-actualization and the inner journey must also challenge the external structures that shape men’s lives.

Nevertheless, at his best, Bly modeled a way of being man that was soulful, heartfelt, and “radically alive.” In a time of profound gender trouble, his vision of an ecological masculinity at home in the web of life remains a potent call. As Bly wrote:

“If a culture does not deal with the warrior energy—take it consciously, discipline it, honor it—it will turn up outside in the form of street gangs, wife beating, drug violence, brutality to children, and aimless murder.”

The task Bly named is now ours to carry forward: to envision a way of being male that joins fierceness and tenderness, spine and heart. For all his contradictions, Bly’s fierce advocacy for the soul remains a summons to every man to stand in his true masculine skin and serve something larger than himself. As Bly urged:

“So the ‘Wild Man’…is not opposed to the King. And the King is not opposed to the Warrior…The true radiant energy in the male does not impose order on the world by force, but…enlightens the world…Any man who has wrestled with his demons long enough…will be able to shift shape and energy in a moment, in order to respond to the needs of a woman and children, or the world. That shape-shifting is the sign of the energy being mastered.”

“The aim is not to be the Wild Man, but to be in touch with the Wild Man…The Wild Man is not opposed to the King; he is the King’s right arm and necessary angel.”

List of Robert Bly’s Publications

- Silence in the Snowy Fields (1962) – Bly’s first poetry collection, which established his reputation as a major American poet with its evocative images of rural life and meditative tone.

- The Light Around the Body (1967) – This collection won the National Book Award and is known for its surreal and political themes, reflecting Bly’s opposition to the Vietnam War.

- Sleepers Joining Hands (1973) – A collection of poems that delve into themes of consciousness and collective human experience.

- Iron John: A Book About Men (1990) – Bly’s most famous work, which uses the Grimm fairy tale to explore masculinity and the process of male initiation.

- The Sibling Society (1996) – A critical examination of contemporary American culture, particularly the decline of mature adulthood and the rise of a society of “siblings.”

- Morning Poems (1997) – A collection of poems written each morning as a daily exercise in creativity and reflection.

- Eating the Honey of Words: New and Selected Poems (1999) – A compilation of Bly’s poetry, showcasing his career-long exploration of the human condition.

- The Maiden King: The Reunion of Masculine and Feminine (1998) – Co-authored with Marion Woodman, this book explores the integration of masculine and feminine energies through myth and psychological analysis.

- The Night Abraham Called to the Stars (2001) – Poems that blend personal reflection with spiritual insight and mythological themes.

- My Sentence Was a Thousand Years of Joy (2005) – A collection of poems that reflect Bly’s ongoing engagement with the themes of love, grief, and the sacred.

- Turkish Pears in August: Twenty-Four Ramages (2007) – A collection of poems that use the ramage form, reflecting on nature, spirituality, and human experience.

- Talking into the Ear of a Donkey (2011) – A later collection of poems that continues Bly’s exploration of personal and collective themes, often with a humorous touch.

Further Reading

Books:

- “Man and His Symbols” by Carl Jung – Essential reading for understanding the Jungian psychology that influenced Bly.

- “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” by Joseph Campbell – Explores the monomyth and mythological structures that Bly drew upon in his work.

- “Fire in the Belly: On Being a Man” by Sam Keen – Another seminal work in the men’s movement, providing context for Bly’s contributions.

- “Iron John and After” by James Hillman – Offers a critical perspective on Bly’s work and its implications for masculinity.

- “The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious” by Carl Jung – A deeper dive into Jungian psychology, essential for understanding Bly’s mythopoetic approach.

Web Resources:

- The Robert Bly Website – Robert Bly Official Website – Contains a wealth of information on Bly’s life, works, and legacy.

- The Jung Page – jungpage.org – Offers resources and articles on Jungian psychology, which heavily influenced Bly’s work.

- Mythic Imagination Institute – mythicjourneys.org – Provides articles and resources on mythology and its application to modern life.

- Men’s Resource Center – menscenter.org – Offers resources and support for men’s issues, reflecting the ongoing influence of Bly’s work.

Bibliography

- Bly, Robert. Silence in the Snowy Fields. Wesleyan University Press, 1962.

- Bly, Robert. The Light Around the Body. Harper & Row, 1967.

- Bly, Robert. Sleepers Joining Hands. Harper & Row, 1973.

- Bly, Robert. Iron John: A Book About Men. Addison-Wesley, 1990.

- Bly, Robert. The Sibling Society. Addison-Wesley, 1996.

- Bly, Robert. Morning Poems. HarperCollins, 1997.

- Bly, Robert. Eating the Honey of Words: New and Selected Poems. HarperCollins, 1999.

- Bly, Robert, and Marion Woodman. The Maiden King: The Reunion of Masculine and Feminine. Henry Holt, 1998.

- Bly, Robert. The Night Abraham Called to the Stars. HarperCollins, 2001.

- Bly, Robert. My Sentence Was a Thousand Years of Joy. HarperCollins, 2005.

- Bly, Robert. Turkish Pears in August: Twenty-Four Ramages. Eastern Washington University Press, 2007.

- Bly, Robert. Talking into the Ear of a Donkey. W. W. Norton & Company, 2011.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

The Symbolism of the Bollingen Stone

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

The Symbolism of Color in Dreams

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jung to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

The Origins and History of Consciousness

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenological Method

The Future of Jungian Thought

Jungian Analysts

0 Comments