Issues in Defining the Self in Psychotherapy

Carl Jung was a seminal thinker whose ideas have penetrated popular culture to a remarkable degree. However, this diffusion has been a double-edged sword, as Jungian concepts have often been simplified, misunderstood, and coopted by various ideological movements. Perhaps no movement has been more guilty of this than the New Age, which has freely borrowed Jungian terms while often stripping them of their original meaning and context. In his book “Jung and the New Age”, David Tacey performs an incisive analysis of how Jungian psychology has been both embraced and distorted by the New Age movement. At the heart of this confusion, Tacey argues, is a fundamental disagreement over the nature of the Self and the goal of psycho-spiritual development.

The New Age: A Regression to Mythic Consciousness

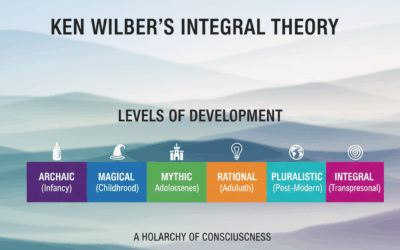

The New Age movement arose in the 1960s and 70s as a reaction against the disenchanted, hyper-rational worldview of modernity. It sought to re-infuse life with a sense of spiritual mystery and purpose that had been lost in the modern era. In this regard, the New Age shared Jung’s critique of the one-sidedness of Western rationality and his desire to reconnect with the archetypal depths of the psyche. However, as Tacey points out, the New Age often commits the opposite error of valorizing a regressive, childlike state of consciousness.

New Age thought tends to idealize a pre-rational, mythic mode of being in which the ego is dissolved in a blissful oceanic feeling of oneness with the universe. It celebrates the “divine child” archetype without recognizing the need for this archetype to mature into an adult spirituality. The New Age encourages an indulgence in archetypal experiences and altered states without the mediating influence of a strong, reality-adapted ego. It mistakes the inflated grandiosity of the ego-Self merger for genuine spiritual realization.

Jung’s Dialogical Self

In contrast, Jung emphasized the importance of engaging archetypal material consciously and dialogically. For Jung, the goal was not to achieve a permanent state of ego-transcendence, but to strengthen the ego through its encounter with the Self. The ego must be able to withstand the numinosity of the unconscious without being overwhelmed or possessed by it. This requires a “religious attitude” of humility and reverence towards the archetypes, combined with a critical, discerning intellect.

Jung’s Self is not a homogeneous unity, but a complexio oppositorum, a union of opposites. It is a paradoxical totality that includes both light and shadow, good and evil, masculine and feminine. Individuation involves withdrawing projections and integrating the shadow, the contra-sexual soul-image (anima/animus), and the spirit archetype of the Wise Old Man or Woman. This is an ongoing, lifelong process of self-knowledge and self-realization, not a quick fix or instant enlightenment.

The Ego-Self Axis

For Jung, the key to psychic wholeness is the establishment of a healthy ego-Self axis. The ego must be strong enough to resist the regressive pull of the unconscious, while also being permeable enough to be guided by the Self. The Self is the supraordinate personality that transcends and includes the ego, not a separate, higher self that replaces the ego. Jung’s model of the psyche preserves the tension between ego and Self, whereas the New Age often seeks to collapse this tension prematurely.

Tacey emphasizes that Jung’s Self is a dynamic, evolving entity, not a static, perfected state. It is the archetype of meaning and purpose that unfolds over the course of a lifetime. Encountering the Self shatters inflated ego-illusions and induces a humbling sense of awe and mystery. It leads not to “self-mastery” but to a recognition of one’s smallness in the face of the vastness of the unconscious.

The Archetypal Roots of Confusion

Jung himself was aware of the ways in which his work could be misinterpreted and misused. He frequently warned against the dangers of inflation, of identifying with archetypes, and of literalizing religious symbols. He insisted that his psychology was empirical and scientific, not metaphysical or esoteric. Yet Jung’s visionary experiences, his mystical writings, and his own mercurial personality all contributed to the aura of enigma surrounding him.

Jung deliberately cultivated an ambiguity and polyvalence in his work, as befitting a Hermetic psychologist. Like Hermes, Jung was a boundary-crosser and a messenger between realms. He intentionally blurred the lines between psychology, religion, philosophy, and the occult in order to shock people out of their one-sided, rational mindset. This liminal, trickster-like quality made Jung an easy target for projection and misinterpretation.

Moreover, Jung’s psychology presupposes a vast knowledge of cultural history, mythology, anthropology, and philosophy that is often lacking in his popularizers. When this broader context is ignored, Jungian concepts can easily be literalized and misappropriated. The archetypes become reified into metaphysical entities rather than being seen as heuristic principles. The process of individuation is reduced to a simplistic formula of self-realization.

Post-Jungian Distortions

Even some of Jung’s most prominent followers have contributed to the confusion surrounding his ideas. Marie-Louise von Franz, for example, tended to present the archetypes in a more literalistic, theological way than Jung himself did. James Hillman rejected the concept of the Self altogether, arguing for a polytheistic model of the psyche composed of multiple, autonomous “soul figures.” While Hillman’s “archetypal psychology” offered a needed corrective to the ego-heroic biases of modern culture, it also risked regressing to a fragmented, dissociated view of the psyche.

Tacey cautions that many contemporary “Jungian” therapies and techniques, such as Voice Dialogue, Active Imagination, and Internal Family Systems (IFS), can easily become vehicles for New Age distortions if they are not grounded in a solid understanding of Jungian theory. There is a danger of reifying the various “parts” or “subpersonalities” and losing sight of the integrative function of the ego and Self. Therapists may unwittingly collude with a client’s inflation or spiritual bypassing in the name of “inner work.”

Authentic Spirituality and Individuation

For Jung, the ultimate goal of individuation is not self-aggrandizement but self-transcendence. It involves a shift from ego-centeredness to Self-centeredness, from a heroic striving for perfection to a humble acceptance of one’s limitations and shadow. Authentic spirituality requires the ability to hold the tension of opposites, to embrace both the light and dark sides of existence.

The New Age, in contrast, often seeks to deny or escape from the shadow, to project it onto external enemies or “negative energies.” It confuses spiritual awakening with ego-inflation and narcissistic self-absorption. It mistakes altered states and paranormal experiences for genuine transformation. In doing so, it shortchanges the depth and complexity of the human psyche.

Tacey argues that the best safeguard against New Age distortions of Jungian thought is a return to the philosophical and anthropological roots of Jung’s ideas. Jung drew heavily on the Western esoteric tradition, particularly alchemy and Gnosticism, which view the Self as an impersonal, suprahuman reality that transcends individual ego-consciousness. He also grounded his psychology in a deep study of world mythology, folklore, and indigenous shamanic practices.

By situating Jung in this broader historical and cross-cultural context, we can appreciate the true radicality and significance of his thought. Jung’s Self is not a New Age fantasy of perfect enlightenment, but a postmodern recognition of the fluid, multivalent nature of identity. The Self is a deconstructive as well as integrative principle, subverting fixed ego-structures and revealing ever-deeper layers of the unconscious.

Re-Visioning Jung for the 21st Century

The confusion between Jung and the New Age is not simply a matter of intellectual misunderstanding, but a manifestation of the archetypal tensions and paradoxes inherent in Jung’s thought. The New Age represents the shadow of Jungian psychology, the tendency to literalize and concretize what are meant to be symbolic and transformative realities. It is an expression of the modern ego’s craving for quick fixes and instant gratification, its desire to bypass the hard work of individuation.

At the same time, the New Age also embodies the utopian longings and spiritual aspirations of the postmodern psyche. It reflects a genuine urge to re-sacrilize a disenchanted world and to reconnect with the archetypal depths of the collective unconscious. The challenge for Jungian thinkers and practitioners today is to honor these aspirations while also grounding them in the rigorous, critical spirit of Jung’s empirical psychology.

This means re-visioning Jung for the 21st century, stripping away the accretions of pop-psychology and New Age distortions to recover the radical, transformative core of his ideas. It means engaging in a serious interdisciplinary dialogue with fields such as neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, ecology, and postcolonial studies. And it means embodying the archetypal principles of Jung’s thought in our own individuation journeys, as we strive to integrate the shadow, the contra-sexual other, and the spirit of the depths into a fuller expression of the Self.

Bibliography

- Tacey, David. Jung and the New Age. Routledge, 2001.

- Jung, C.G. The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Edited by Gerhard Adler, Michael Fordham, and Herbert Read. Princeton University Press, 1953-1992.

- Shamdasani, Sonu. Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. HarperCollins Publishers, 1992.

- Von Franz, Marie-Louise. Projection and Re-Collection in Jungian Psychology. Open Court Publishing Company, 1980.

- Stein, Murray. Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court Publishing Company, 1998.

- Edinger, Edward F. The Aion Lectures: Exploring the Self in C.G. Jung’s Aion. Inner City Books, 1996.

- Tarnas, Richard. The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View. Ballantine Books, 1993.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. SUNY Press, 1998.

Further Reading

- Bair, Deirdre. Jung: A Biography. Little, Brown and Company, 2004.

- Chodorow, Joan. Jung on Active Imagination. Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Corbin, Henry. The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy. North Atlantic Books, 1998.

- Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Hannah, Barbara. Jung: His Life and Work. Chiron Publications, 1991.

- Jacobi, Jolande. The Way of Individuation. New American Library, 1967.

- Neumann, Erich. The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Owens, Lance S. Jung and Aion: Time, Vision, and a Wayfaring Man. Psychological Perspectives: A Quarterly Journal of Jungian Thought, Vol. 54 (2011), pp. 253-289.

- Samuels, Andrew. Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge, 1986.

- Schwartz-Salant, Nathan. The Mystery of Human Relationship: Alchemy and the Transformation of the Self. Routledge, 1998.

- Stein, Murray. The Principle of Individuation: Toward the Development of Human Consciousness. Chiron Publications, 2006.

- Stein, Murray. The Red Book: A Reader’s Edition. W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

- Stevens, Anthony. Jung: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Stevens, Anthony. On Jung. Princeton University Press, 1990.

- Storr, Anthony. The Essential Jung: Selected and Introduced by Anthony Storr. Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Young-Eisendrath, Polly and Hall, James A. Jung’s Self Psychology: A Constructivist Perspective. The Guilford Press, 1991.

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

The Symbolism of the Bollingen Stone

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

The Symbolism of Color in Dreams

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jung to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

The Origins and History of Consciousness

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenological Method

The Future of Jungian Thought

0 Comments