Throughout history, mystics, philosophers, and wisdom traditions from around the world have independently arrived at strikingly similar insights into the nature of the human psyche, the path to healing and wholeness, and the fundamental structure of reality. These recurring patterns and themes, often referred to as the perennial philosophy, point to a universal substratum of human experience that transcends cultural and historical boundaries.

In the 20th century, the pioneering work of depth psychologists such as Carl Jung, along with the emergence of somatic and experiential therapies, has begun to bridge the gap between these ancient wisdom traditions and the modern scientific understanding of the mind. Despite facing criticism for their often subjective and phenomenological approach, these fields have uncovered profound parallels between the insights of the mystics and the lived experience of individuals in the therapeutic process.

In this article, we will explore the connections between the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies, highlighting the universal patterns that emerge across these seemingly disparate domains. We will argue that the recurrence of these themes, independently discovered by individuals and traditions separated by time and space, constitutes a form of empirical evidence for the deep structures of the human psyche and the transformative power of certain practices and ways of knowing.

The Perennial Philosophy and the Collective Unconscious

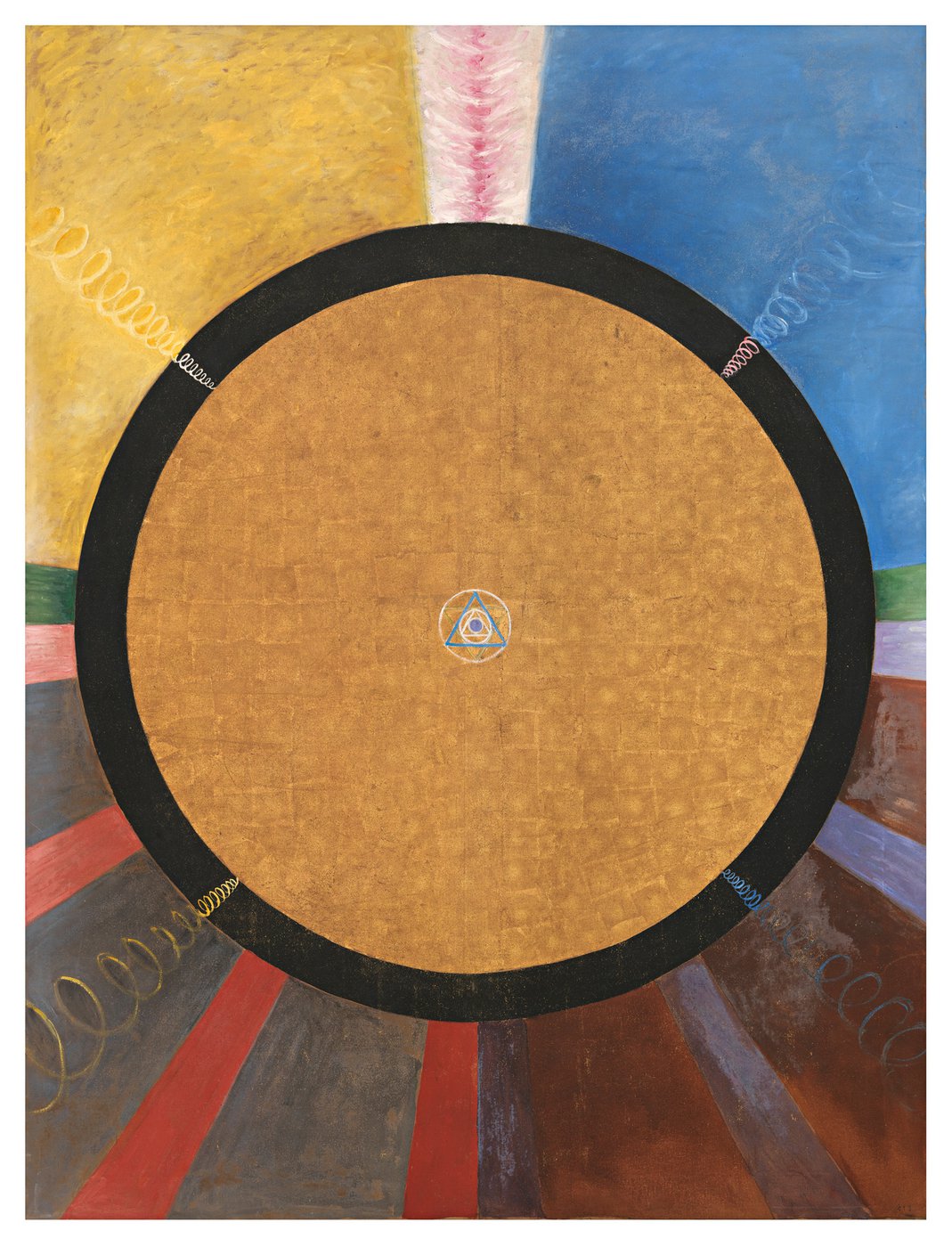

At the heart of the perennial philosophy lies the idea that beneath the surface diversity of human cultures and belief systems, there exists a common core of spiritual wisdom and insight. This universal knowledge, which has been articulated in various forms by mystics, sages, and philosophers throughout history, points to the fundamental unity of all things and the possibility of direct, experiential knowledge of this ultimate reality.

One of the key figures in bringing the perennial philosophy into dialogue with modern psychology was Carl Jung, whose concept of the collective unconscious bears a striking resemblance to the idea of a universal ground of being. For Jung, the collective unconscious was a deep layer of the psyche that contained archetypal patterns and images shared by all of humanity. These archetypes, which manifest in symbols, myths, and dreams across cultures, were seen by Jung as evidence of the universality of certain aspects of human experience.

Jung’s understanding of the collective unconscious was heavily influenced by his study of various wisdom traditions, including Gnosticism, alchemy, and Eastern philosophies such as Taoism and Buddhism. He saw in these traditions a common thread of insight into the nature of the psyche and the path to wholeness and self-realization. However, Jung’s reliance on subjective experience and his openness to non-empirical ways of knowing led to criticism from some quarters of the scientific community, who saw his ideas as unverifiable and unfalsifiable.

Somatic Therapies and the Wisdom of the Body

In recent decades, the emergence of somatic and body-oriented therapies has brought a new dimension to the dialogue between ancient wisdom traditions and modern psychology. These approaches, which include practices such as Somatic Experiencing, Hakomi, and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, emphasize the role of the body in psychological healing and transformation.

At the core of somatic therapies lies the idea that the body holds a deep wisdom and intelligence that can be accessed through mindful attention and non-verbal communication. This wisdom, which is often buried beneath layers of tension, trauma, and conditioning, is seen as a powerful resource for healing and self-discovery. By working directly with the felt sense of the body, somatic therapists aim to help individuals access and integrate this embodied knowledge, leading to greater wholeness and resilience.

The emphasis on the wisdom of the body in somatic therapies echoes the insights of many ancient wisdom traditions, which have long recognized the importance of embodied practice and the unity of mind and body. In traditions such as yoga, qigong, and tai chi, the cultivation of bodily awareness and the harmonization of energy and breath are seen as essential aspects of spiritual development and self-realization. Similarly, practices such as meditation and mindfulness, which have been embraced by many somatic therapists, have deep roots in contemplative traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism.

Theme 1: The Transpersonal Dimension of the Psyche

The Role of the Unconscious and the Mystery of the Self

“The unconscious is not just a repository of forgotten memories; it is the source of all that is creative and meaningful in human life.”

— Carl Jung

Art therapy can help you tap into the subcorticle brain and mystical space

One of the central themes that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the idea of a deeper, transpersonal dimension of the psyche that transcends the individual ego and connects us to a larger whole. This dimension, variously referred to as the Self, the Tao, the Atman, or the collective unconscious, is seen as the source of wisdom, creativity, and healing.

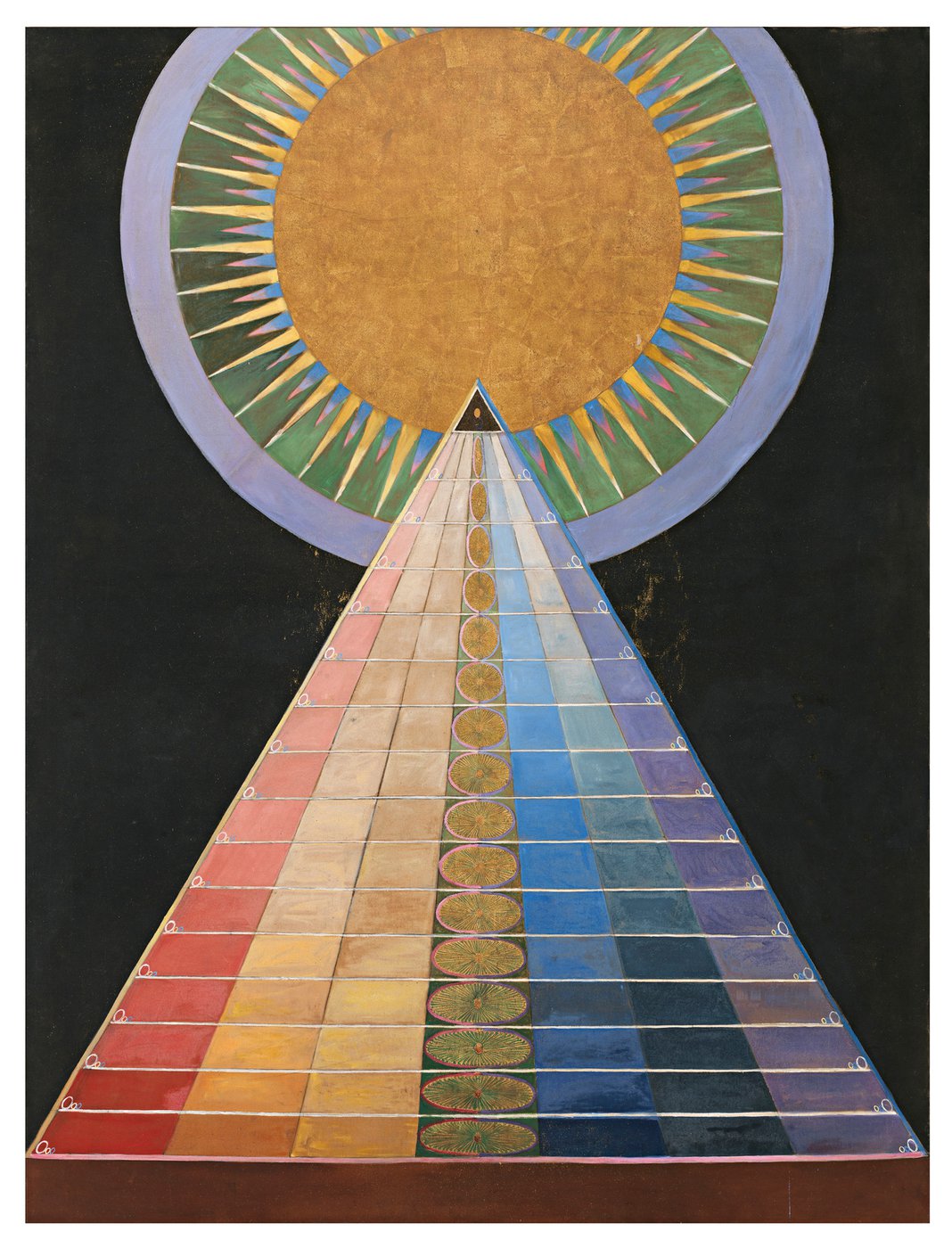

In the perennial philosophy, this transpersonal dimension is often described as the ultimate ground of being, the divine spark within each individual that connects us to the infinite. Mystics and sages throughout history, from Plotinus to Meister Eckhart to Ramana Maharshi, have pointed to this deeper reality as the true nature of the self and the key to spiritual liberation.

In depth psychology, the transpersonal dimension is often associated with the concept of the Self, which Carl Jung saw as the central archetype of wholeness and the guiding principle of the individuation process. For Jung, the Self represents the totality of the psyche, encompassing both the conscious and unconscious aspects of the individual, and serving as a bridge to the collective unconscious and the archetypal realm.

In somatic therapies, the transpersonal dimension is often accessed through the felt sense of the body and the deep wisdom and intelligence that lies beneath the surface of conscious awareness. Somatic practitioners work with the body as a gateway to the unconscious, using techniques such as focusing, embodied mindfulness, and non-verbal communication to help individuals connect with the deeper aspects of their being.

Across these various approaches, the recognition of a transpersonal dimension of the psyche challenges the dominant Western view of the self as a separate, isolated entity, and points to a more interconnected and holistic understanding of human nature. By acknowledging and cultivating a connection to this deeper reality, individuals can access a greater sense of meaning, purpose, and wholeness in their lives.

Neurobiology of the Transpersonal Dimension of the Psyche

Modern neuroscience offers intriguing insights into the biological basis of transpersonal experiences and their psychological significance. Studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) suggest that mystical, self-transcendent, and transpersonal states involve specific alterations in brain activity, particularly in the default mode network (DMN). The DMN, which includes the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and precuneus, is responsible for self-referential thought and ego-based processing. During deep meditation, psychedelic experiences, and mystical states, this network shows decreased activity, correlating with the dissolution of the ego and the experience of unity with a larger whole.

Neurochemical changes also accompany transpersonal states. Psychedelic research suggests that substances such as psilocybin and DMT, which modulate serotonin 2A receptors in the brain, facilitate ego dissolution and heightened connectivity between brain regions that normally do not communicate extensively. Similarly, contemplative practices such as meditation and breathwork increase gamma wave coherence in the brain, which has been associated with heightened awareness, insight, and non-dual experiences.

Moreover, research on neuroplasticity indicates that repeated engagement in transpersonal practices such as mindfulness and deep meditative absorption can lead to structural changes in the brain. Long-term meditators show increased cortical thickness in regions associated with self-awareness and interoception, such as the insula and anterior cingulate cortex, suggesting that accessing the transpersonal dimension is not merely a fleeting state but can lead to lasting neurobiological transformations.

Additionally, the social reward system, mediated by oxytocin and dopamine, plays a role in reinforcing states of connection and unity. Feelings of transcendence often co-occur with a sense of deep social or existential belonging, activating neural pathways similar to those involved in maternal bonding and pro-social behavior. This suggests that transpersonal experiences may serve an adaptive function, promoting social cohesion and well-being by reducing excessive self-focus and increasing feelings of interconnectedness.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the transpersonal dimension of the psyche may not be purely metaphysical but is deeply rooted in the neurobiology of consciousness. The brain’s ability to shift between egoic self-referential processing and transpersonal states reflects a dynamic interplay between different neural networks, supporting the idea that human consciousness is capable of accessing realms beyond the individual self.

Theme 2: The Integration of the Psyche

The Importance of Integration and Wholeness

“The wound is the place where the Light enters you.”

— Rumi

Another key theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the importance of integrating and harmonizing the various aspects of the psyche, including the conscious and unconscious, the mind and body, and the masculine and feminine. This integration is often seen as a key aspect of the process of individuation or self-realization.

In the perennial philosophy, the idea of integration is often framed in terms of the reconciliation of opposites and the transcendence of dualism. Mystics and sages throughout history have emphasized the need to embrace and integrate the full spectrum of human experience, from the light to the dark, the sacred to the profane, the spiritual to the material.

In depth psychology, the process of integration is central to the concept of individuation, which Carl Jung saw as the ultimate goal of psychological development. For Jung, individuation involves the integration of the conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche, the confrontation with the shadow, and the development of a more authentic and wholesome sense of self. Other depth psychologists, such as James Hillman and Marie-Louise von Franz, have further explored the process of integration in terms of the balance between the masculine and feminine principles of the psyche.

In somatic therapies, the integration of the psyche is often approached through the lens of the mind-body connection and the healing of trauma and early developmental wounds. Somatic practitioners work with the body as a storehouse of unresolved experiences and emotions, using techniques such as Somatic Experiencing and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy to help individuals integrate these fragments of the self and develop a more coherent and resilient sense of embodied presence.

Across these various approaches, the process of integration is seen as a gradual and often challenging journey that requires patience, perseverance, and a willingness to confront the shadow aspects of the self. By working to integrate the various dimensions of the psyche, individuals can develop a greater sense of wholeness, authenticity, and self-acceptance, and cultivate a more harmonious and fulfilling way of being in the world.

Neurobiology of Integration and Psyche Harmonization

The process of psychological integration—the unification of the conscious and unconscious, the mind and body, and the masculine and feminine aspects of the psyche—has clear neurobiological correlates. At its core, integration is a function of neural connectivity, emotional regulation, and the resolution of internal conflicts that are stored within the nervous system.

One of the most relevant neurological systems involved in this process is the prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in self-awareness, executive functioning, and emotional regulation. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in particular is involved in the integration of autobiographical memory and affective states, allowing for the synthesis of disparate aspects of the self. When individuals engage in depth psychological work, mindfulness, or somatic therapies, they strengthen connections between the mPFC and subcortical structures such as the amygdala, which processes emotions, and the hippocampus, which consolidates memory. This integration helps regulate overwhelming emotions, transform unconscious material into conscious awareness, and create a more cohesive narrative of the self.

The concept of balancing opposites within the psyche also has neurobiological underpinnings. The brain operates through a dynamic interplay between different hemispheres and neural networks. The left hemisphere, typically associated with analytical and linguistic processing, has been linked to traditionally “masculine” cognitive functions such as logic and categorization. The right hemisphere, which is more involved in holistic, intuitive, and emotional processing, aligns with what Jungian psychology might describe as the “feminine” principle. Psychological integration may involve greater inter-hemispheric communication via the corpus callosum, leading to a more balanced and flexible cognitive style.

Additionally, polyvagal theory provides insight into the mind-body aspect of integration. The autonomic nervous system (ANS), particularly the vagus nerve, regulates states of safety, connection, and threat response. Individuals who have unresolved trauma or psychological fragmentation often show dysregulation in the ANS, oscillating between hyperarousal (sympathetic dominance) and shutdown (dorsal vagal activation). Somatic therapies work by facilitating the regulation of the nervous system, helping individuals transition from states of dissociation or hyperreactivity to a more balanced, socially engaged mode of functioning. This process allows for the embodied integration of previously disconnected or repressed experiences.

Finally, research on neuroplasticity suggests that the integration of the psyche is not merely an abstract psychological process but is physically encoded in the brain. Mindfulness, therapy, and deep introspective work can lead to structural and functional changes, strengthening neural pathways that support self-awareness, emotional balance, and resilience. As individuals engage in practices that promote integration—such as dream work, active imagination, somatic therapy, or meditation—they are reinforcing neural circuits that facilitate psychological wholeness.

In essence, the neurobiology of integration reveals that the harmonization of the psyche is an embodied process, deeply tied to neural networks, emotional regulation, and physiological states. The journey of individuation is thus not only a psychological and spiritual endeavor but also a profoundly biological one, requiring the rewiring and reorganization of the nervous system to support greater coherence, resilience, and authenticity.

Theme 3: The Role of Symbolism and Myth

The Healing Power of Love and Compassion

“Love is the only reality, and it is not a mere sentiment. It is the ultimate truth that lies at the heart of creation.”

— Rainer Maria Rilke

The labyrinth in the christian church is used as a mystical symbol for self discovery

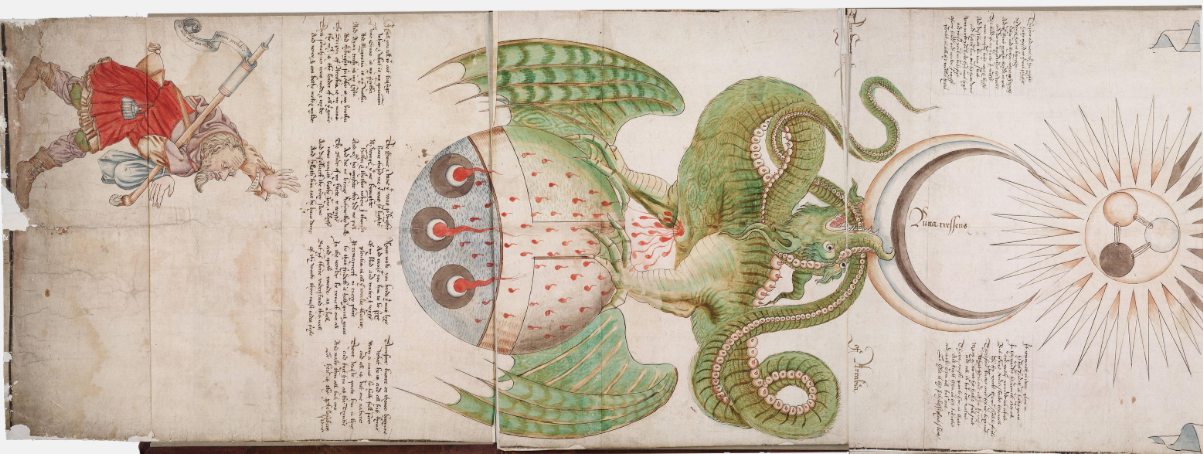

A third theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the central role of symbolism, myth, and archetypal patterns in mediating between the conscious and unconscious dimensions of the psyche. These symbolic languages are seen as a way of accessing and integrating the deeper wisdom of the psyche and connecting us to the larger patterns of human experience.

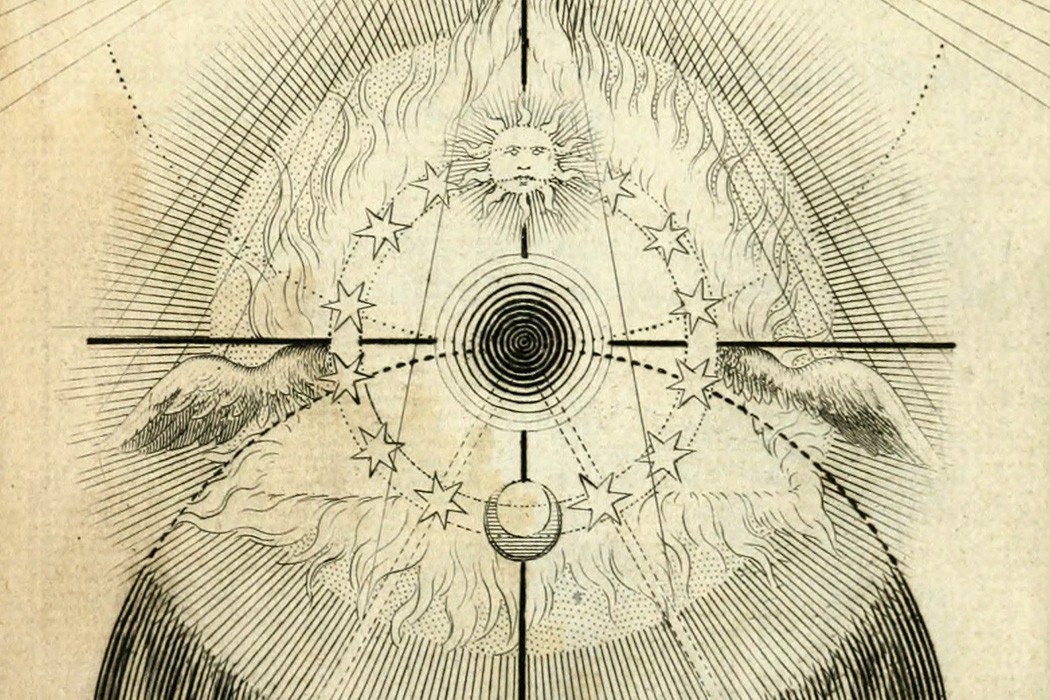

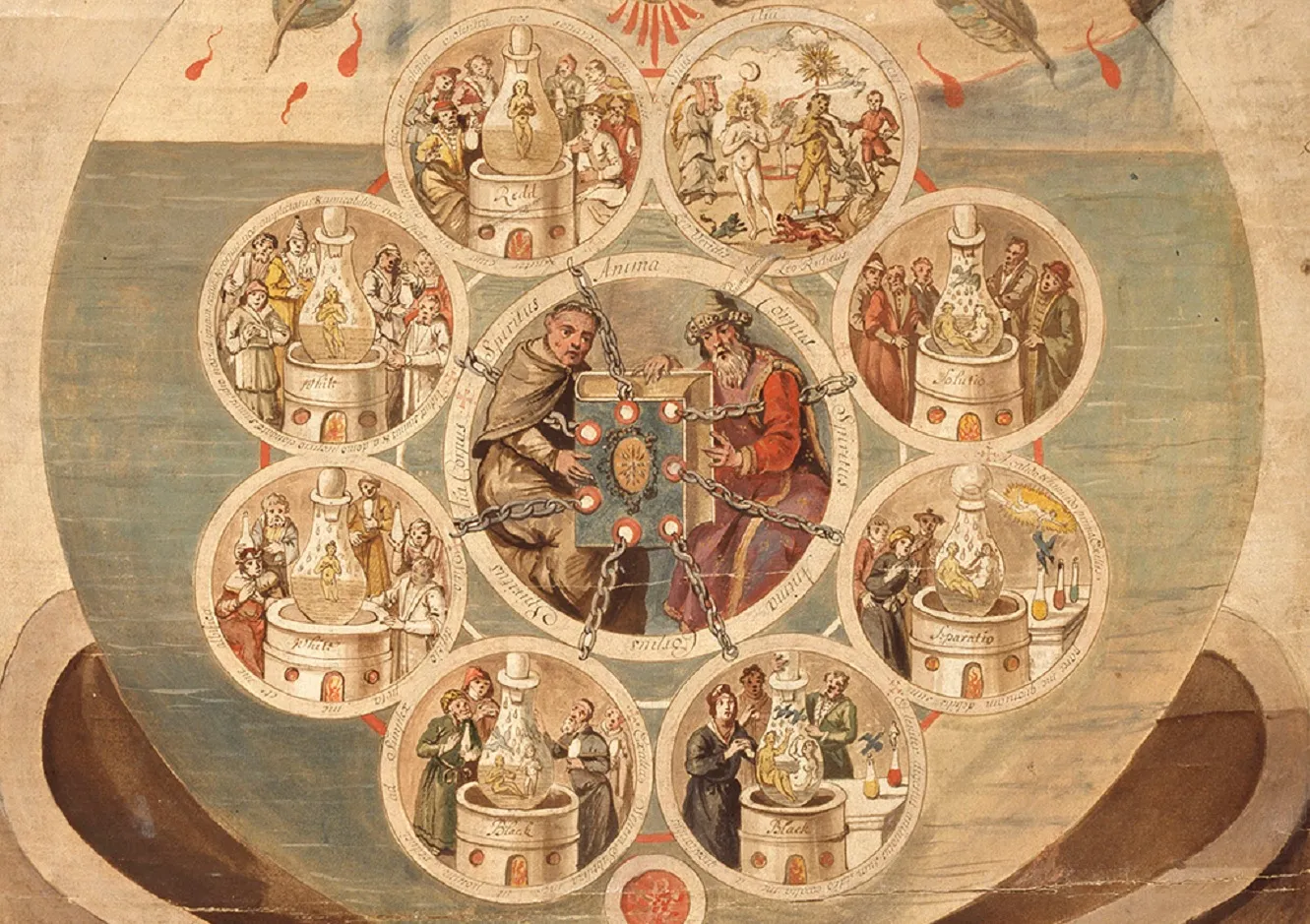

In the perennial philosophy, the use of symbols and mythic narratives is a central feature of many spiritual traditions, from the parables of Jesus to the koans of Zen Buddhism to the alchemical imagery of medieval Europe. These symbolic languages are seen as a way of pointing beyond the literal and conceptual mind to the deeper reality of the spirit, and of evoking a direct, experiential knowledge of the sacred.

In depth psychology, the exploration of symbols and myths is central to the work of Carl Jung and his followers. For Jung, symbols were the language of the unconscious, and the study of myths, fairy tales, and dreams was a key way of accessing the archetypal patterns and themes that shape our psyche. Jung saw the process of individuation as a symbolic journey of self-discovery, in which the individual confronts and integrates the various archetypes and complexes that make up the psyche.

In somatic therapies, the use of symbolism and myth is often more implicit, but no less significant. Somatic practitioners work with the body as a living symbol of the psyche, using movement, gesture, and touch to access and integrate the deeper layers of experience and meaning. The body itself is seen as a storehouse of mythic and archetypal patterns, from the hero’s journey of overcoming trauma to the alchemical process of transformation and rebirth.

Across these various approaches, the recognition of the power of symbolism and myth challenges the dominant Western view of language as a purely literal and conceptual tool, and points to the importance of cultivating a more imaginal and poetic approach to the psyche. By engaging with the symbolic dimensions of experience, individuals can access a deeper sense of meaning and purpose, and connect with the timeless patterns and themes that shape the human journey.

Neurobiology of Symbolism, Myth, and Archetypal Patterns

The human brain is inherently wired to perceive, process, and respond to symbols and archetypal patterns, a capacity deeply rooted in its neurobiological structure. At the core of this symbolic cognition is the interplay between the limbic system, which governs emotional and instinctual responses, and the neocortex, which facilitates higher-order meaning-making. This dynamic allows myths and symbols to serve as powerful mediators between conscious thought and unconscious processes.

The right hemisphere of the brain plays a key role in processing symbolic and metaphorical information. Unlike the left hemisphere, which is more linear and analytical, the right hemisphere excels at recognizing patterns, making associative connections, and engaging with nonverbal, imaginal forms of knowledge. Neuroimaging studies have shown that engagement with stories, myths, and symbols activates brain regions such as the medial prefrontal cortex and the temporoparietal junction, which are associated with perspective-taking, self-referential thought, and empathy. This suggests that archetypal narratives help shape our sense of identity and connection to collective human experience.

On a deeper level, the limbic system—particularly the amygdala and hippocampus—contributes to the emotional salience of symbols. The amygdala assigns emotional weight to experiences, while the hippocampus integrates these experiences into memory, allowing symbolic imagery to carry deep personal and cultural significance. This explains why certain mythic themes, such as the hero’s journey or the struggle between light and darkness, resonate across cultures and epochs—they are rooted in the universal neurobiological processes that structure our perception of the world.

Additionally, the default mode network (DMN), which becomes active during introspection, dreaming, and spontaneous thought, plays a crucial role in symbolic processing. The DMN facilitates the generation of narratives, personal meaning-making, and the integration of disparate aspects of experience into a coherent sense of self. This is particularly relevant in depth psychology, where active imagination and dream analysis rely on the brain’s ability to synthesize unconscious material into symbolic form.

Somatic therapies further highlight the embodied nature of symbolism. The brain’s sensorimotor networks, particularly the insula and somatosensory cortex, process bodily sensations and translate them into meaningful emotional experiences. This explains why bodily movements, postures, and felt sensations often carry archetypal significance—our very physiology participates in the symbolic language of the psyche. The process of working with these somatic symbols, such as in dance therapy or trauma work, can facilitate profound psychological integration by bridging the gap between preverbal, embodied experience and conscious awareness.

From a neurobiological perspective, myths and symbols are not mere abstractions but fundamental to how the brain organizes meaning, processes emotions, and integrates experience. Engaging with symbolic material—whether through storytelling, dream analysis, or somatic expression—activates neural networks that promote emotional regulation, self-awareness, and the resolution of psychological conflicts. This underscores the timeless human need for myth and metaphor as a means of accessing deeper layers of wisdom and transformation.

Theme 4: The Wisdom of the Body

Embodiment and the Wisdom of the Body

“The body is the servant of the mind. It obeys the operations of the mind, whether they be deliberately chosen or automatically expressed.”

— James Allen

A fourth theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the significance of embodied experience and the wisdom of the body in the process of healing and transformation. The body is seen not merely as a physical vessel, but as a repository of lived experience, emotional memory, and untapped potential.

In the perennial philosophy, the body is often seen as a microcosm of the larger cosmos, containing within it the same patterns and energies that animate the universe as a whole. Many spiritual traditions, such as yoga, qigong, and tai chi, work directly with the body as a way of cultivating spiritual awareness and transformation, using practices such as asana, pranayama, and energetic healing to harmonize the mind, body, and spirit.

In depth psychology, the body has often been overlooked in favor of a more mental and symbolic approach to the psyche. However, Carl Jung himself recognized the importance of the body in the individuation process, and saw practices such as active imagination and dream work as a way of bridging the gap between the conscious and unconscious mind. Later depth psychologists, such as James Hillman and Marion Woodman, have further explored the role of the body in psychological healing and transformation.

In somatic therapies, the body is the central focus of the work, and the cultivation of embodied awareness and experience is seen as the key to healing and growth. Somatic practitioners work with the body as a living, breathing, feeling organism, using techniques such as Somatic Experiencing, Hakomi, and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy to help individuals access and integrate the deeper layers of bodily experience. The body is seen as a source of innate wisdom and intelligence, and the process of healing involves learning to listen to and trust the messages and sensations that arise from the body.

Across these various approaches, the recognition of the wisdom of the body challenges the dominant Western view of the mind-body split, and points to the importance of cultivating a more holistic and integrated approach to human experience. By learning to listen to and trust the wisdom of the body, individuals can access a greater sense of wholeness, vitality, and self-regulation, and develop a more grounded and authentic way of being in the world.

Neurobiology of Embodied Experience and the Wisdom of the Body

The recognition of the body as a repository of lived experience and emotional memory is deeply supported by contemporary neuroscience. The body is not merely a passive vessel for the mind but an active participant in perception, cognition, and healing. The interplay between the brain, nervous system, and bodily sensations shapes our sense of self, emotional regulation, and capacity for transformation.

At the core of embodied experience is the nervous system, particularly the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which regulates our physiological responses to stress and safety. The ANS operates through two primary branches: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which governs fight-or-flight responses, and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which facilitates rest, digestion, and healing. The vagus nerve, a key component of the PNS, plays a crucial role in social engagement, emotional regulation, and the felt sense of safety. Somatic therapies that emphasize breathwork, movement, and interoception (awareness of internal body sensations) help to regulate the ANS, fostering resilience and restoring a sense of balance.

The insular cortex, a region of the brain responsible for integrating bodily sensations with emotions and self-awareness, is central to the experience of embodied consciousness. The insula processes signals from the body—such as heartbeat, breath, and gut sensations—and translates them into emotional and intuitive awareness. Studies have shown that practices like mindfulness, yoga, and body-based therapies enhance insular function, leading to increased emotional attunement, self-regulation, and interoceptive accuracy. This suggests that cultivating awareness of bodily sensations can deepen self-understanding and promote healing.

Trauma research has further revealed that unresolved emotional experiences are stored in the body, often manifesting as chronic tension, pain, or dissociation. The work of researchers such as Bessel van der Kolk has demonstrated that traumatic memories are encoded not just in the brain’s cognitive centers but also in the somatosensory system. The amygdala, which detects threat and generates emotional responses, can become hyperactive after trauma, leading to heightened vigilance and somatic distress. Somatic therapies, including Somatic Experiencing and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, work by gently reprocessing these embodied memories, allowing for integration and nervous system regulation.

Movement and gesture also play a fundamental role in shaping psychological experience. The motor cortex and basal ganglia govern movement, but they are also deeply intertwined with emotional expression and nonverbal communication. Practices such as dance therapy, tai chi, and expressive movement engage these neural pathways, helping to release stuck emotions and cultivate a sense of aliveness. Research has shown that engaging in rhythmic, embodied movement activates the brain’s reward system, particularly the release of dopamine and endorphins, which enhance mood and promote a sense of connection.

The neurobiology of embodied experience underscores that healing and transformation are not merely cognitive processes but deeply rooted in the felt sense of the body. By tuning into bodily sensations, regulating the nervous system, and engaging in embodied practices, individuals can access profound states of self-awareness, emotional integration, and psychological wholeness. This perspective challenges the traditional Western dualism of mind and body, affirming the wisdom of the body as an essential guide in the journey of healing and self-realization.

Theme 5: The Centrality of Relationship

Surrender and Transcendence

“Let yourself be silently drawn by the strange pull of what you really love. It will not lead you astray.”

— Rumi

A fifth theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the centrality of relationship and interpersonal dynamics in the therapeutic process. Whether in the form of the therapist-client relationship, the guru-disciple relationship, or the sangha or spiritual community, the presence of a supportive and attuned other is seen as essential for growth and healing.

In the perennial philosophy, the importance of spiritual friendship and community is emphasized in many traditions, from the Sangha of Buddhism to the Satsang of Hinduism to the mystical fellowship of Christianity. These communities provide a context of support, guidance, and accountability for individuals on the spiritual path, and help to anchor the insights and experiences of the individual in a larger context of shared meaning and purpose.

In depth psychology, the therapeutic relationship is seen as a crucial container for the process of individuation and psychological growth. Carl Jung emphasized the importance of the “therapeutic alliance” between therapist and client, and saw the transference and countertransference dynamics of the relationship as a key arena for the confrontation and integration of unconscious material. Other depth psychologists, such as Heinz Kohut and Donald Winnicott, have further explored the role of empathy, mirroring, and holding in the therapeutic relationship.

In somatic therapies, the relationship between therapist and client is often even more central, as the work involves a direct, bodily engagement with the client’s experience. Somatic practitioners emphasize the importance of attunement, resonance, and co-regulation in the therapeutic relationship, and see the therapist’s own embodied presence as a key tool for facilitating the client’s healing and growth. Techniques such as touch, movement, and breath work are often used to deepen the connection between therapist and client and to access the deeper layers of the client’s bodily experience.

Across these various approaches, the recognition of the centrality of relationship challenges the dominant Western view of the individual as a separate, self-contained entity, and points to the importance of cultivating a more relational and interconnected understanding of human nature. By recognizing the healing power of authentic, attuned relationships, individuals can access a greater sense of support, belonging, and wholeness, and develop a more compassionate and empathic way of being in the world.

Neurobiological Foundations of Interpersonal Connection

Neuroscientific research increasingly supports the idea that relationship and interconnectedness are central to human experience. Studies using qEEG and fMRI have demonstrated that social bonds and attachment relationships activate the brain’s reward system, particularly the release of oxytocin and the engagement of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for emotional regulation and theory of mind, plays a crucial role in attunement and empathy, enabling individuals to navigate complex social interactions. Additionally, research on the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia has shown how early relational experiences shape behavioral patterns, reinforcing or inhibiting social engagement strategies. The default mode network (DMN), which is active during introspection and self-referential thinking, has been found to synchronize with others during meaningful social interactions, suggesting a neural basis for the experience of connection and shared meaning. These findings align with the insights of depth psychology and somatic therapy, providing a biological basis for the transformative power of authentic relationships.

Theme 6: Surrender and Transcendence

The Cyclical Nature of Growth

“What the caterpillar calls the end of the world, the master calls a butterfly.”

— Richard Bach

A sixth theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the importance of surrender, letting go, and transcending the ego in the process of spiritual growth and self-realization. This often involves a confrontation with the shadow aspects of the psyche and a willingness to embrace the unknown and the numinous.

In the perennial philosophy, the idea of surrender is central to many spiritual traditions, from the Islamic concept of Islam (which literally means “submission” to God) to the Christian notion of kenosis (the emptying out of the self to make room for the divine) to the Buddhist practice of letting go of attachment and aversion. These traditions recognize that the ego, with its grasping and defending, is often the main obstacle to spiritual growth, and that a radical surrendering of the self is necessary for true transformation to occur.

In depth psychology, the process of surrender is often framed in terms of the confrontation with the shadow and the death of the ego. Carl Jung saw the shadow as the repressed or rejected aspects of the self that must be integrated for wholeness to occur, and the death of the ego as a necessary stage in the individuation process. Other depth psychologists, such as Stanislav Grof and Karlfried Graf Dürckheim, have further explored the transformative potential of surrendering to the numinous and the transpersonal dimensions of the psyche.

In somatic therapies, the process of surrender is often approached through the lens of letting go of muscular and emotional holding patterns in the body. Somatic practitioners work with the body as a way of accessing and releasing the deep-seated tensions and traumas that keep individuals stuck in limiting patterns of thought and behavior. Techniques such as Somatic Experiencing, Hakomi, and Bioenergetics involve a gradual and gentle process of surrendering to the wisdom of the body and allowing the natural healing processes of the organism to unfold.

Across these various approaches, the recognition of the importance of surrender and transcendence challenges the dominant Western view of the self as a separate, autonomous agent, and points to the necessity of letting go of the ego’s grasping and controlling tendencies in order to access a deeper sense of wholeness and integration. By cultivating a willingness to embrace the unknown and the numinous, individuals can open themselves up to the transformative power of grace and the deepest dimensions of their being.

Neurobiology of Surrender and Transcendence

The experience of surrender and transcendence is deeply embedded in the neurobiology of the brain, nervous system, and body. Letting go of egoic control and opening to a larger sense of self involves dynamic shifts in neural networks, physiological responses, and the integration of unconscious material. Research in neuroscience, particularly on altered states of consciousness, flow states, and spiritual experiences, has revealed key mechanisms that underlie the process of surrender.

One of the central neurobiological processes involved in surrender is the downregulation of the default mode network (DMN), a network of brain regions including the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex. The DMN is responsible for self-referential thought, autobiographical memory, and the maintenance of the egoic sense of self. Studies on meditation, psychedelics, and near-death experiences have shown that when the DMN is quieted, individuals often report a sense of ego dissolution, increased interconnectedness, and direct encounters with the numinous. This temporary suppression of self-focused cognition allows for a deeper immersion into transpersonal awareness, similar to what mystics have described across cultures.

The limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, also plays a crucial role in the process of surrender. The amygdala, which governs fear responses, must be sufficiently regulated for an individual to feel safe enough to release control. This is why many somatic therapies focus on titration—gradually working with distressing experiences in small, manageable doses—to allow for integration without overwhelming the nervous system. The hippocampus, which is involved in memory consolidation and contextualizing experiences, helps reframe surrender as a meaningful and potentially transformative process rather than a threat to survival.

Neurotransmitters and hormones also facilitate the experience of surrender and transcendence. Oxytocin, often called the “bonding hormone,” is released during deep states of trust, connection, and spiritual experience. High levels of oxytocin can enhance feelings of surrender by fostering a sense of safety and openness. Similarly, serotonin and dopamine play roles in generating feelings of bliss and transcendence, whether through meditation, breathwork, or other altered states. Endorphins, released during deep relaxation and peak experiences, contribute to the ecstatic states often described in spiritual literature.

From a somatic perspective, surrender involves a shift from sympathetic nervous system dominance (fight-or-flight) to parasympathetic activation (rest-and-digest). The vagus nerve, particularly the ventral vagal branch, plays a key role in this transition. When the vagus nerve is stimulated through deep breathing, chanting, or gentle bodywork, the body enters a state of relaxation and receptivity, making surrender more accessible. This physiological shift allows for a softening of muscular holding patterns, the release of tension, and a deepening into embodied presence.

Across spiritual, psychological, and somatic traditions, the process of surrender involves both a neurobiological and existential shift. It requires moving beyond the conditioned fear of letting go, rewiring the nervous system for safety and trust, and quieting the cognitive structures that maintain the illusion of control. By engaging practices that regulate the nervous system and allow for egoic dissolution—such as meditation, breathwork, movement, or deep relational attunement—individuals can access profound states of transcendence and transformation. This neurobiological perspective reinforces what mystical traditions and depth psychology have long recognized: that true self-realization emerges not from control, but from surrendering into the vast, interconnected depths of the psyche.

Theme 7: The Cyclical Nature of Growth

Direct Experience and Embodied Knowing

“When you look at the world with the eyes of the heart, the whole world becomes a mirror.”

— Lao Tzu

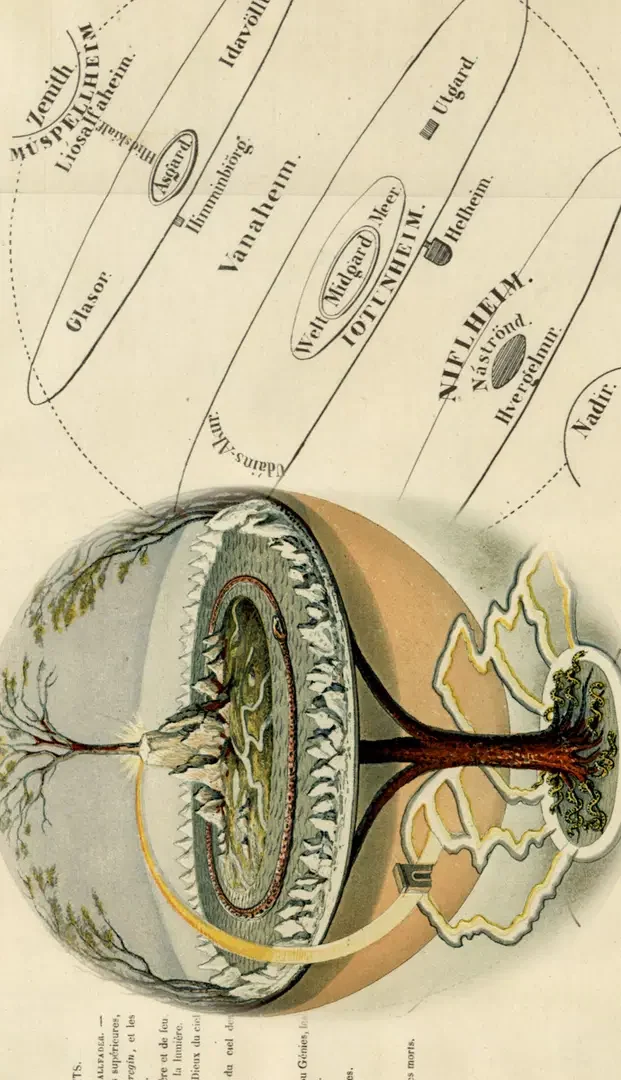

A seventh theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the recognition of the cyclical and dialectical nature of growth and transformation, involving periods of crisis, dissolution, and regeneration. This pattern is often symbolized by the mythic motif of death and rebirth, or the alchemical process of nigredo, albedo, and rubedo.

In the perennial philosophy, the idea of cyclical growth is reflected in many spiritual traditions, from the Hindu notion of samsara (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth) to the Buddhist understanding of the three turnings of the wheel of dharma to the Christian concept of the paschal mystery (the death and resurrection of Christ). These traditions recognize that growth is not a linear process, but rather involves repeated cycles of death and rebirth, as the old self is shed and a new, more integrated self emerges.

In depth psychology, the cyclical nature of growth is often framed in terms of the confrontation with the shadow and the integration of unconscious material. Carl Jung saw the individuation process as involving repeated cycles of crisis and renewal, as the ego is challenged and transformed by the encounter with the unconscious. Other depth psychologists, such as Stanislav Grof and Arnold Mindell, have further explored the transformative potential of crisis and the importance of working with the “process” of the psyche as it unfolds over time.

In somatic therapies, the cyclical nature of growth is often approached through the lens of the body’s natural healing processes. Somatic practitioners recognize that healing is not a linear process, but rather involves repeated cycles of activation and deactivation, as the body releases old patterns and integrates new experiences. Techniques such as Somatic Experiencing and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy involve working with the body’s natural rhythms and cycles, and supporting the client’s capacity to self-regulate and maintain equilibrium in the face of stress and challenge.

Across these various approaches, the recognition of the cyclical nature of growth challenges the dominant Western view of progress as a linear and cumulative process, and points to the importance of embracing the ups and downs of the transformative journey. By learning to work with the natural cycles of crisis and renewal, individuals can develop a greater capacity for resilience, adaptability, and self-renewal, and cultivate a more dynamic and fluid sense of self.

Theme 8: Direct Experience and Embodied Knowing

Interconnectedness and Non-Duality

“I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.”

— Carl Jung

An eighth theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the emphasis on direct, experiential knowledge and the limitations of purely intellectual or conceptual understanding. Wisdom traditions and experiential therapies alike stress the importance of lived experience and embodied knowing, rather than mere belief or theory.

In the perennial philosophy, the primacy of direct experience is reflected in the emphasis on contemplative practices such as meditation, prayer, and ritual. These practices are designed to cultivate a direct, unmediated encounter with the sacred, beyond the realm of concepts and beliefs. Many traditions, such as Zen Buddhism and Sufism, emphasize the importance of “tasting” the truth directly, rather than merely understanding it intellectually.

In depth psychology, the importance of direct experience is reflected in the emphasis on the therapeutic process itself as a transformative journey. Carl Jung saw the therapy room as a alchemical vessel in which the prima materia of the client’s psyche could be transformed through the direct encounter with the unconscious. Other depth psychologists, such as James Hillman and Michael Meade, have emphasized the importance of storytelling, myth, and ritual as ways of accessing the deep, imaginal dimensions of the psyche.

In somatic therapies, the emphasis on direct experience is even more pronounced, as the body itself becomes the primary vehicle for knowing and transformation. Somatic practitioners work with the felt sense of the body as a way of accessing the deep, pre-verbal dimensions of experience that are often inaccessible to the conscious mind. Techniques such as Focusing and Authentic Movement involve a direct, embodied encounter with the inner landscape of the psyche, beyond the realm of concepts and beliefs.

Across these various approaches, the emphasis on direct experience challenges the dominant Western view of knowledge as a purely intellectual or objective pursuit, and points to the importance of cultivating a more participatory and embodied way of knowing. By learning to trust the wisdom of direct experience, individuals can access a deeper sense of meaning, purpose, and connection, and cultivate a more authentic and integrated way of being in the world.

Neurobiology of Cyclical Growth and Transformation

The cyclical nature of psychological and spiritual growth is deeply rooted in neurobiology. Transformation occurs not as a steady, linear progression but through iterative cycles of activation, breakdown, and integration. This dynamic process is reflected in the way the nervous system, brain, and body metabolize stress, process trauma, and adapt to new experiences.

One key neurobiological mechanism that underlies cycles of crisis and renewal is the autonomic nervous system (ANS), particularly the interplay between the sympathetic (fight-or-flight) and parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) branches. Growth and transformation often involve periods of heightened arousal—whether emotional distress, existential crisis, or deep introspection—followed by phases of consolidation and integration. The pendulation between these states mirrors the expansion-contraction cycles seen in biological and psychological healing. Somatic therapies such as Somatic Experiencing work with these natural oscillations, helping individuals move between activation and regulation without becoming stuck in chronic dysregulation.

Neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself in response to new experiences—is also inherently cyclical. Growth requires periods of instability in which old neural patterns are disrupted, allowing for the emergence of new pathways. During moments of crisis, the brain undergoes an adaptive process of synaptic pruning and rewiring, much like the alchemical motif of dissolution and rebirth. This process is supported by neuromodulators such as dopamine, which facilitates learning and motivation, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which promotes neuronal growth and adaptability.

The limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, also plays a key role in cyclical transformation. The amygdala processes emotional intensity, signaling moments of perceived threat or profound change, while the hippocampus contextualizes these experiences, helping integrate them into a coherent narrative. When individuals face emotional upheaval or existential crisis, these structures work in tandem to encode meaning and facilitate the transition to a new phase of growth.

From a somatic perspective, the cyclical nature of growth is mirrored in the body’s physiological rhythms. The process of homeostasis and allostasis—where the body seeks equilibrium while adapting to stressors—illustrates how growth unfolds through alternating phases of disequilibrium and reorganization. Trauma resolution follows a similar pattern, as the body moves between activation (re-experiencing) and settling (integration). Somatic therapies harness this rhythm, using techniques such as titration and pendulation to guide clients through healing cycles without overwhelm.

Across spiritual, psychological, and biological dimensions, growth follows a nonlinear trajectory, marked by phases of crisis, dissolution, and renewal. The recognition of this cyclical pattern challenges the Western ideal of continuous upward progress and invites a deeper trust in the natural rhythms of transformation. By aligning with these cycles—rather than resisting them—individuals can cultivate resilience, allowing each phase of breakdown to serve as fertile ground for renewal.

Theme 9: The Sacred and the Numinous

Compassion and the Alleviation of Suffering

“Compassion is the keen awareness of the interdependence of all things.”

— Thomas Merton

A ninth theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the acknowledgment of the sacred and the numinous dimensions of existence, and the role of spiritual practice and ritual in facilitating healing and transformation. Many traditions and therapies incorporate elements of prayer, meditation, and sacred ceremony as a way of accessing these transpersonal realms.

In the perennial philosophy, the recognition of the sacred is central to the understanding of the nature of reality and the human condition. Many traditions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity, see the ultimate goal of human life as the realization of the divine or the sacred within oneself and the world. Spiritual practices such as meditation, prayer, and ritual are seen as ways of cultivating a direct encounter with the numinous and facilitating the process of spiritual transformation.

In depth psychology, the recognition of the sacred is reflected in the emphasis on the archetypal and mythological dimensions of the psyche. Carl Jung saw the psyche as inherently religious, and believed that the process of individuation involved a confrontation with the archetypal forces of the collective unconscious. Other depth psychologists, such as James Hillman and Rudolf Otto, have further explored the numinous dimensions of the psyche and the role of the sacred in psychological healing and transformation.

In somatic therapies, the recognition of the sacred is often more implicit, but no less significant. Many somatic practitioners incorporate elements of spiritual practice and ritual into their work, such as mindfulness meditation, yoga, and shamanic journeying. These practices are seen as ways of accessing the deeper, transpersonal dimensions of the psyche and facilitating a more holistic and integrated approach to healing.

Across these various approaches, the acknowledgment of the sacred and the numinous challenges the dominant Western view of reality as a purely material and mechanistic realm, and points to the importance of cultivating a more reverential and awe-inspired approach to life. By learning to recognize and honor the sacred dimensions of existence, individuals can access a deeper sense of meaning, purpose, and connection, and cultivate a more compassionate and reverent way of being in the world.

Neurobiology of Direct Experience and Embodied Knowing

The neurobiological foundation of direct experience and embodied knowing is grounded in the intricate relationship between the brain, body, and nervous system. Unlike intellectual or conceptual forms of understanding, which rely heavily on cortical processing and the symbolic representation of information, embodied knowing is deeply connected to the limbic system, the brainstem, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). These systems are integral to our ability to directly experience and process sensations, emotions, and bodily states.

At the core of embodied experience is interoception—the brain’s ability to sense and interpret signals from within the body. The insula, a region of the brain responsible for processing interoceptive information, plays a crucial role in integrating sensory data from the body with emotional and cognitive states. This integration allows us to “know” in a way that bypasses the need for conceptualization or mental labels, enabling us to directly experience the wisdom inherent in our body’s sensations. This is central to somatic therapies, which help individuals tune into their internal landscape through techniques such as Focusing, Authentic Movement, and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy. These practices facilitate the cultivation of a felt sense, wherein individuals access non-verbal and pre-cognitive dimensions of experience, often leading to profound insights and healing.

Furthermore, embodied knowing is not confined solely to the conscious brain; it is deeply interwoven with the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which regulates physiological states such as heart rate, respiration, and digestion. The ANS governs our automatic, unconscious responses to emotional and physical stimuli, and its balance is vital for health, resilience, and well-being. In somatic therapies, the practitioner works with the ANS to help clients regulate and release held emotions, traumas, and tensions. For example, the regulation of the vagus nerve, which governs parasympathetic responses such as relaxation, is a key focus in trauma-sensitive practices. The ability to achieve autonomic regulation fosters an embodied awareness that can lead to a deeper connection to the present moment and the internal wisdom of the body.

In addition, the brain’s neuroplasticity underpins the process of embodied knowing. Neural pathways are continuously shaped and reshaped by direct sensory experiences, especially those tied to emotional states. Repeated, embodied practices such as meditation, movement, and bodywork allow for the rewiring of these pathways, reinforcing the mind-body connection and enhancing the capacity for self-regulation and resilience. Studies have shown that practices like mindfulness meditation and somatic-based therapies can enhance cortical regions related to self-awareness and emotional regulation, highlighting the transformative power of direct, experiential practices.

Moreover, embodied knowing engages a unique neural system that integrates sensory, emotional, and cognitive processes—the mirror neuron system. Mirror neurons, found in areas such as the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobes, are responsible for empathy and the imitation of actions, and they play a vital role in somatic practices. When individuals engage in practices like Authentic Movement or in therapeutic storytelling, they often experience a deep, embodied resonance with the material or with the therapist’s own experience, allowing for integration of unconscious material into conscious awareness.

Across these disciplines, the emphasis on direct experience challenges the dominance of abstract, intellectual approaches to knowledge in Western culture. From a neurobiological perspective, this shift is rooted in the recognition that the body, brain, and nervous system collectively house immense wisdom that transcends cognitive understanding. By cultivating the capacity to experience and trust this embodied knowing, individuals can access deeper layers of awareness, healing, and self-transformation.

Theme 10: Interconnectedness and Non-Duality

Narrative and Meaning-Making

“We are our stories, and the stories we tell ourselves shape our lives.”

— Clarissa Pinkola Estés

A tenth theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the understanding of the interconnectedness and interdependence of all things, and the recognition of the self as a microcosm of the larger whole. This holistic worldview is often expressed through the language of non-duality, the web of life, or the universal mind.

In the perennial philosophy, the idea of interconnectedness is central to the understanding of the nature of reality and the human condition. Many traditions, such as Vedanta, Taoism, and Buddhism, emphasize the fundamental unity and interdependence of all phenomena, and see the individual self as a temporary and illusory construct. The goal of spiritual practice is often described as the realization of this essential non-duality and the dissolution of the ego into the larger whole.

In depth psychology, the understanding of interconnectedness is reflected in the concept of the collective unconscious and the recognition of the archetypal dimensions of the psyche. Carl Jung saw the individual psyche as embedded in a larger matrix of collective patterns and forces, and believed that the process of individuation involved a confrontation with these transpersonal dimensions. Other depth psychologists, such as Erich Neumann and Stanislav Grof, have further explored the holographic nature of the psyche and the ways in which the individual reflects the larger patterns of the cosmos.

In somatic therapies, the understanding of interconnectedness is often approached through the lens of the body as a microcosm of the larger ecosystem. Many somatic practitioners work with the idea of the “body-mind” as a unified and interconnected system, and see the individual as embedded in a larger web of relationships and environments. Techniques such as ecopsychology and nature-based therapy involve a direct encounter with the natural world as a way of facilitating a more holistic and integrated approach to healing.

Across these various approaches, the understanding of interconnectedness and non-duality challenges the dominant Western view of the self as a separate and isolated entity, and points to the importance of cultivating a more relational and ecological approach to life. By learning to recognize the fundamental unity and interdependence of all things, individuals can access a deeper sense of belonging, purpose, and connection, and cultivate a more compassionate and sustainable way of being in the world.

The Neurobiology of Interconnectedness and Non-Duality

The neurobiology of interconnectedness and non-duality can be understood through the study of how the brain and body process experiences of unity, wholeness, and collective interconnectedness. Neuroplasticity, mirror neurons, and the default mode network (DMN) all play significant roles in the embodied experience of non-duality and the recognition of interconnectedness.

One of the key aspects of understanding interconnectedness from a neurobiological perspective is the concept of neural integration. Neural integration refers to the ability of the brain to connect various regions in a coherent manner, allowing for a holistic experience of self, others, and the environment. The default mode network (DMN), a network of brain regions including the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and the inferior parietal lobe, has been linked to self-referential thinking, which is often implicated in the ego’s sense of separateness. However, research shows that practices such as meditation and mindfulness, which aim to cultivate an experience of non-duality, can lead to a decrease in DMN activity, resulting in a feeling of greater interconnectedness with the world. As the DMN quiets, individuals report a diminished sense of the “self” as separate and an increased sense of unity with the larger whole.

Mirror neurons also play a role in our understanding of interconnectedness. These neurons, which are activated when we observe the actions of others, are crucial for empathy and social bonding. They allow us to “feel” others’ emotions and experience their actions as if they were our own. This neural mechanism underlies our capacity for compassion and a deeper sense of connection with others. Somatic therapies that encourage embodied presence, such as Authentic Movement and Somatic Experiencing, rely on this mirror neuron system to foster attunement between therapist and client, allowing individuals to experience a more integrated and relational sense of self.

Additionally, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a crucial role in our experience of interconnectedness. The parasympathetic nervous system (associated with relaxation and healing) is activated in practices that promote unity and non-duality, such as deep breathing, grounding exercises, and nature-based therapies. These practices help clients engage with their environment and relationships in a more attuned, harmonious way, reinforcing the neurobiological foundations of interdependence.

The role of the vagus nerve also illustrates the deep biological connection between mind and body. The vagus nerve is central to regulating the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs the body’s ability to self-regulate and experience calmness. Research suggests that practices that stimulate the vagus nerve, such as deep breathing, singing, or even engaging with nature, promote a sense of connectedness to the larger world by helping to release stress and trauma held in the body.

Finally, the understanding of the body-mind connection in somatic therapies highlights the way in which the body stores emotional memory and reflects the larger, interconnected ecosystem. The practice of tuning into somatic sensations, feelings, and movements is based on the neurobiological principle that the body holds both the individual and collective experiences. Somatic therapies aim to activate and release these embodied memories, facilitating a more integrated and harmonious sense of self within the web of life.

By incorporating these neurobiological insights, individuals engaging with perennial philosophy, depth psychology, or somatic therapies are able to deepen their sense of non-duality and interconnectedness, moving beyond the illusion of separateness to experience their place within a larger, unified whole. This integrated understanding not only promotes psychological and emotional well-being but also fosters a sense of belonging, interconnectedness, and responsibility toward the collective.

Theme 11: Compassion and the Alleviation of Suffering

Mystery and Unknowing

“Not knowing is the most intimate.”

— John Keats

An eleventh theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the value placed on compassion, empathy, and the alleviation of suffering as the ultimate goal of spiritual practice and psychotherapy. Wisdom traditions and therapeutic approaches alike emphasize the cultivation of compassion for self and other as a key aspect of healing and awakening.

In the perennial philosophy, the importance of compassion is reflected in the central ethical teachings of many traditions, such as the Golden Rule of Christianity, the bodhisattva vow of Mahayana Buddhism, and the principle of ahimsa (non-violence) in Hinduism and Jainism. These teachings emphasize the fundamental equality and dignity of all beings, and the importance of cultivating a heart of compassion and concern for the welfare of others.

In depth psychology, the importance of compassion is reflected in the emphasis on empathy, acceptance, and unconditional positive regard in the therapeutic relationship. Carl Rogers, the founder of humanistic psychology, saw the therapist’s ability to offer a non-judgmental and empathic presence as the key to facilitating the client’s growth and self-actualization. Other depth psychologists, such as Heinz Kohut and Arthur Janov, have further explored the role of empathy and compassion in healing early developmental wounds and promoting psychological integration.

In somatic therapies, the importance of compassion is often approached through the lens of the body as a source of wisdom and a vehicle for healing. Many somatic practitioners work with the idea of “somatic empathy” as a way of attuning to the client’s bodily experience and offering a compassionate and non-judgmental presence. Techniques such as Hakomi, Somatic Experiencing, and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy involve a gentle and compassionate approach to working with trauma and developmental wounds, and emphasize the importance of self-compassion and self-care in the healing process.

Across these various approaches, the emphasis on compassion and the alleviation of suffering challenges the dominant Western view of the individual as a self-interested and competitive entity, and points to the importance of cultivating a more caring and altruistic approach to life. By learning to extend compassion and empathy to oneself and others, individuals can access a deeper sense of connection, purpose, and meaning, and contribute to the creation of a more just and harmonious world.

The Neurobiology of Compassion and the Alleviation of Suffering

The neurobiology of compassion highlights the profound impact that cultivating empathy, care, and compassion has on both individual well-being and interpersonal relationships. Understanding the brain’s role in the experience of compassion offers insight into how practices in perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies foster healing, alleviate suffering, and create lasting change.

One of the key neurobiological mechanisms involved in compassion is the activation of the mirror neuron system. These neurons allow us to recognize and empathize with the emotions and actions of others. When we see someone in distress, our mirror neurons fire as though we are experiencing their feelings ourselves. This shared neural experience forms the biological basis of empathy and compassion, allowing us to feel connected to others’ suffering and respond with care and understanding.

Additionally, the oxytocin system plays a central role in compassion. Often referred to as the “love hormone,” oxytocin is released in response to nurturing behaviors, social bonding, and acts of kindness. Research has shown that oxytocin fosters a sense of connection and trust, reducing stress and promoting prosocial behaviors. In therapeutic contexts, such as somatic therapies and depth psychology, the empathic attunement between therapist and client can trigger the release of oxytocin, reinforcing a compassionate healing environment. Practices such as mindfulness meditation and loving-kindness meditation have also been shown to increase oxytocin levels, promoting greater compassion toward oneself and others.

Another key neurobiological factor in the alleviation of suffering is the regulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Compassionate acts and feelings of empathy help to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, the branch of the ANS responsible for promoting relaxation and healing. In contrast to the fight-or-flight response, the parasympathetic system encourages a state of calm and safety, allowing the body to rest, digest, and repair. Somatic therapies often target this system, helping clients shift out of states of chronic stress, trauma, and hyperarousal into a more balanced state of physiological regulation. Techniques such as grounding, breathwork, and embodied presence help activate the parasympathetic nervous system, fostering a compassionate environment that supports healing.

The prefrontal cortex is also essential in the regulation of compassion and empathy. This area of the brain is involved in higher-order functions, such as perspective-taking, decision-making, and regulating emotions. Studies have shown that engaging in compassion-focused practices, such as meditation or therapeutic techniques aimed at emotional processing, increases prefrontal cortex activity. This enhanced function supports individuals in shifting from reactive, emotionally driven responses to more thoughtful, compassionate behaviors that help reduce suffering, both within themselves and in their interactions with others.

Furthermore, epigenetic research has demonstrated that compassionate behaviors can influence gene expression, suggesting that engaging in practices of kindness and empathy can lead to changes at the molecular level that promote emotional and physical healing. This finding underscores the power of compassion not only to alleviate suffering in the moment but also to create long-term physiological and psychological changes.

Across these neurobiological perspectives, the importance of compassion in healing becomes clear. By fostering compassion through therapeutic work, mindfulness, and embodied practices, individuals are not only addressing emotional wounds and suffering but also engaging in a process that can lead to profound neurobiological healing and transformation. As compassion becomes ingrained in an individual’s neural and physiological systems, it becomes a natural, embodied response that serves as a foundation for a more connected, integrated, and harmonious way of being in the world.

Theme 12: Narrative and Meaning-Making

The Importance of Integration and Wholeness

“Out of the fire, the furnace, the light of being; wholeness is a true and beautiful state of human existence.”

— Eckhart Tolle

A twelfth theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the recognition of the power of narrative, story, and meaning-making in shaping our experience and identity. Wisdom traditions and therapeutic approaches alike explore the role of personal and collective myths in structuring our sense of self and world.

In the perennial philosophy, the importance of narrative is reflected in the central role of myth, legend, and sacred story in many traditions. These narratives are seen not merely as entertaining tales, but as powerful vehicles for transmitting spiritual truths and shaping the collective imagination. From the Homeric epics of ancient Greece to the Bhagavad Gita of Hinduism to the parables of Jesus, these stories serve as templates for understanding the human condition and the path to spiritual realization.

In depth psychology, the importance of narrative is reflected in the emphasis on the role of personal myth and archetypal story in shaping the psyche. Carl Jung saw the process of individuation as involving the creation of a new personal myth, one that integrates the conscious and unconscious dimensions of the self and provides a sense of meaning and purpose. Other depth psychologists, such as James Hillman and Rollo May, have further explored the role of myth and story in shaping the psyche and the importance of cultivating a poetic and imaginative approach to life.

In somatic therapies, the importance of narrative is often approached through the lens of the body as a storyteller and a repository of personal and collective history. Many somatic practitioners work with the idea of the “body narrative” as a way of accessing the deep, embodied dimensions of the client’s experience and facilitating a more integrated and meaningful sense of self. Techniques such as Authentic Movement and Dance/Movement Therapy involve a direct encounter with the body’s stories and a process of creative meaning-making through movement and expression.

Across these various approaches, the recognition of the power of narrative and meaning-making challenges the dominant Western view of reality as an objective and value-neutral realm, and points to the importance of cultivating a more poetic and imaginative approach to life. By learning to engage with the stories and myths that shape our experience, individuals can access a deeper sense of meaning, purpose, and identity, and contribute to the creation of a more beautiful and enchanted world.

The Neurobiology of Narrative and Meaning-Making

The neurobiology of narrative and meaning-making sheds light on the profound impact that stories, both personal and collective, have on the brain and our sense of identity. Neuroscience shows that the process of creating, processing, and internalizing narratives involves complex interactions between various regions of the brain, highlighting the power of storytelling in shaping our experience and emotional lives.

At the core of this process is the default mode network (DMN), a network of brain regions that is activated when we are engaged in self-referential thought, daydreaming, or reflecting on personal experiences. The DMN plays a crucial role in constructing our personal narrative, allowing us to create coherent stories about our past, present, and future. This network is deeply involved in memory, imagination, and meaning-making, and it is through these cognitive processes that we are able to weave our experiences into a meaningful narrative.

Research has shown that when individuals engage in therapeutic practices that involve storytelling—such as those found in depth psychology or somatic therapies—there is increased activity in the DMN, suggesting that these practices facilitate the construction of a more integrated and cohesive sense of self. In psychotherapy, telling one’s story can help organize fragmented experiences and emotions, providing a sense of coherence and continuity. This process of narrative construction is essential for healing, as it allows individuals to make sense of their suffering, losses, and struggles, thereby transforming them into meaningful chapters of their personal myth.

Another key region involved in the process of meaning-making is the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for higher-order functions such as decision-making, perspective-taking, and the regulation of emotions. The prefrontal cortex allows us to interpret and assign meaning to our experiences, helping us to create a narrative framework that guides our actions and choices. For example, when individuals undergo trauma therapy or engage in somatic therapies like Focusing or Authentic Movement, the prefrontal cortex works alongside the body’s sensory system to process and reframe painful memories into a more adaptive and meaningful story.

The hippocampus, which is central to the formation and retrieval of memories, also plays a crucial role in narrative construction. This region helps us connect past experiences with present circumstances, enabling us to draw on our memories to create a narrative thread that links our individual experiences together. In therapies such as Dance/Movement Therapy and Somatic Experiencing, the body serves as a vehicle for accessing memories stored in the hippocampus, offering an embodied approach to meaning-making that goes beyond words. This embodied storytelling allows individuals to process experiences that may have been too difficult or traumatic to express verbally, facilitating the integration of those memories into a coherent narrative.

On a more collective level, the mirror neuron system plays a role in the way we connect with the stories of others. These neurons enable us to resonate with the emotions and actions of those around us, fostering empathy and understanding. This neural resonance is particularly powerful in the context of shared stories, such as myths, legends, and sacred narratives. Whether through reading, listening, or participating in collective rituals, humans have an innate ability to connect with the stories that shape the culture and society in which they live. By engaging with these collective myths, individuals can find a sense of belonging and shared purpose, reinforcing their sense of identity within a larger social and spiritual context.

Finally, neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself and form new neural connections—suggests that the act of creating and engaging with new narratives has the potential to reshape the brain itself. When individuals participate in therapeutic practices that encourage storytelling, movement, or imaginative exploration, they can rewire their brain to adopt new perspectives and ways of being. This process of neuroplasticity enables personal transformation, as individuals redefine their sense of self and the meaning of their experiences.

In summary, the neurobiology of narrative and meaning-making reveals the deep, interconnected relationship between the brain, body, and mind in shaping our personal and collective stories. By engaging with and transforming the narratives that structure our lives, we not only gain insight into our own experiences but also contribute to the larger tapestry of meaning and connection that binds humanity together. Through this process, the brain and body undergo a profound transformation, leading to greater healing, integration, and a more profound sense of self.

Theme 13: Mystery and Unknowing

The Healing Power of Love and Compassion

“You, yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.”

— Buddha

A thirteenth and final theme that emerges across the perennial philosophy, depth psychology, and somatic therapies is the acknowledgment of the mystery and ultimate unknowability of the depths of the psyche and the nature of reality. Despite their many insights and maps of the territory, wisdom traditions and depth psychology alike maintain a sense of humility and awe in the face of the great mystery of existence.

In the perennial philosophy, the recognition of mystery is reflected in the apophatic or negative theology of many traditions, which emphasizes the ultimate ineffability and transcendence of the divine. From the Upanishadic doctrine of neti neti (“not this, not that”) to the Christian mysticism of Meister Eckhart and John of the Cross, these traditions point to the limitations of conceptual understanding and the necessity of a direct, experiential encounter with the mystery of being.

In depth psychology, the recognition of mystery is reflected in the acknowledgment of the ultimately unknowable depths of the psyche and the limitations of rational understanding. Carl Jung saw the unconscious as a vast and uncharted territory, filled with numinous and archetypal forces that could never be fully mapped or controlled by the conscious mind. Other depth psychologists, such as Wilfred Bion and Michael Eigen, have further explored the importance of “negative capability” and the capacity to tolerate uncertainty and unknowing in the therapeutic process.

In somatic therapies, the recognition of mystery is often approached through the lens of the body as a gateway to the ineffable and the numinous. Many somatic practitioners work with the idea of “somatic spirituality” as a way of accessing the deeper, transpersonal dimensions of experience that lie beyond the reach of the conscious mind. Techniques such as Holotropic Breathwork and Hakomi involve a direct encounter with the mystery of the body and the psyche, and a willingness to surrender to the unknown and the unexpected in the healing process.

Across these various approaches, the acknowledgment of mystery and unknowing challenges the dominant Western view of knowledge as a linear and cumulative process, and points to the importance of cultivating a more humble and open-ended approach to life. By learning to embrace the ultimately unknowable depths of the psyche and the cosmos, individuals can access a deeper sense of wonder, awe, and reverence, and contribute to the creation of a more mysterious and enchanted world.

The Neuroscience of Mystery and Unknowing

The acknowledgment of mystery and unknowing, as explored across wisdom traditions, depth psychology, and somatic therapies, invites a reflection on the inherent uncertainty and complexity of both the psyche and the nature of reality. From a neurobiological perspective, the experience of mystery and the encounter with the unknown activate a range of brain regions associated with awe, curiosity, and the tolerance of ambiguity. Understanding how the brain engages with mystery, uncertainty, and unknowing deepens our appreciation for these themes, showing how they are not merely philosophical concepts but also integral to our neurological and emotional experience.