What part of the brain is responsible for religion?

“The Self is the ordering and unifying center of the total psyche (conscious and unconscious) just as the ego is the center of the conscious personality. Or, put in other words, the ego is the seat of subjective identity while the Self is the seat of objective identity. The Self is thus the supreme psychic authority and subordinates the ego to it. The Self is most simply described as the inner empirical deity and is identical with the imago Dei.”

― Edward F. Edinger, Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche

Have you ever wondered what makes humans unique in their ability to experience and interpret the world in a spiritual or religious way? Recent studies in neuroscience and evolutionary psychology suggest that the answer may lie in a small but powerful region of the brain called the precuneus.

The precuneus, located in the posterior part of the medial parietal lobe, serves as a bridge or connector within the brain, linking different functional networks that had never been linked before. It’s important to note that the precuneus isn’t about intelligence itself – many animals have brains that are just as smart or even smarter than humans in certain areas. Instead, the precuneus allows different parts of the brain involved in processing information to communicate and observe each other. This is what sets us apart as humans and gives rise to consciousness.

According to Margaret Boone Rappaport, a scholar in the field of evolutionary psychology, the expansion of the precuneus throughout the course of human evolution has enabled us to move beyond mere information processing and engage in the perception and interpretation of our experiences in a way that assigns meaning and significance to our lives (Rappaport, 2020).

In terms of subjective experience, the precuneus is involved in self-awareness, mental imagery, and introspection. It allows us to reflect on our own lives and experiences, as well as to consider the inner worlds and emotional perceptions of other creatures. This has been a huge challenge that humanity has grappled with through various fields like psychology, sociology, anthropology, theology, and philosophy.

This idea is echoed in the work of Edward Edinger, a prominent Jungian analyst and author of the book “Ego and Archetype.” Edinger suggests that the emergence of religious capacity in humans is closely tied to the development of the ego, which he sees as a product of the evolution of the brain and the increasing complexity of human consciousness (Edinger, 1972). According to Edinger, the ego serves as a mediator between the conscious and unconscious mind, allowing us to integrate our experiences and assign meaning to them in a way that gives rise to religious and spiritual beliefs.

As the joke goes, God took a perfectly good monkey and gave it anxiety. But this anxiety is a byproduct of the precuneus and its role in human consciousness. Before the emergence of the precuneus, the brain was simply processing information. After the precuneus developed, the brain began perceiving information, leading to the emergence of anxiety and other existential concerns.

Recent studies have shown that the precuneus is involved in the default mode network (DMN), a set of brain regions that are active when an individual is not focused on a specific task, but instead engaged in self-referential thought or mind-wandering (Raichle et al., 2001). This process of integrating information and generating new ideas may have been crucial in the development of religious and spiritual concepts, which often involve the synthesis of personal experiences, cultural beliefs, and abstract ideas.

Around 30,000 BCE, as the world was undergoing dramatic changes like the extinction of the cave bear and the formation of the Scandinavian ice sheet, early humans began to engage in symbolic thought and meaning-making. The Venus of Willendorf, a stone figurine of a fertile woman, is one of the earliest examples of this.

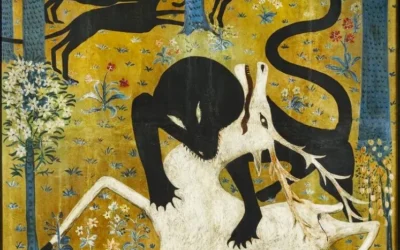

The development of the precuneus and the emergence of symbolic thought and meaning-making can be seen as a kind of “fall from Eden.” Whereas before, humans were part of the natural world and operated on instinct, the precuneus allowed us to develop a sense of self separate from nature. This led to the creation of world mythologies that describe a primal garden or ocean from which humanity was plucked.

The precuneus and the emergence of human consciousness also gave rise to social networks and the formation of tribes, families, and other groups. Just as neurons in the brain work together to perform complex tasks, humans form interconnected networks that allow us to function as a species. These social networks can be seen as external neural networks that help us make meaning and understand ourselves in relation to others.

However, the emergence of consciousness and symbolic thought also created new challenges for humans. We became aware of time, mortality, and the need to find meaning and purpose in life. Religion and spirituality emerged as ways to confront these existential horrors and to tolerate the guilt and shame that come with being human.

As Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung have noted, religion and mythology serve important psychological functions in helping us integrate the shadow aspects of ourselves and find meaning in life. But as theologian John Dominic Crossan points out, we must be careful not to take these stories literally, but rather to understand them as symbolic representations of deep truths about the human experience.

The evolution of the precuneus has played a significant role in shaping the unique cognitive abilities of modern humans, including our capacity for religious and spiritual thought. By enabling us to move beyond mere information processing and engage in the perception and interpretation of our experiences, the precuneus has allowed us to assign meaning and significance to our lives in a way that gives rise to religious and spiritual beliefs. The shift from simply processing information to perceiving information led to the emergence of anxiety and other existential concerns that have shaped the human experience.

As we continue to explore the complex relationship between the brain and human experience, the role of the precuneus in the emergence of religious capacity serves as a reminder of the profound impact that evolutionary changes can have on our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. So the next time you find yourself pondering life’s big questions, remember – it’s all thanks to that little powerhouse in the back of your head.

Bibliography:

Newberg, A., & Waldman, M. R. (2009). How God Changes Your Brain: Breakthrough Findings from a Leading Neuroscientist. Ballantine Books. Beauregard, M., & O’Leary, D. (2007). The Spiritual Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Case for the Existence of the Soul. HarperOne. Persinger, M. A. (1987). Neuropsychological Bases of God Beliefs. Praeger. Kaplan, J. T., & Iacoboni, M. (2006). Getting a grip on other minds: Mirror neurons, intention understanding, and cognitive empathy. Social Neuroscience, 1(3-4), 175-183. Trimble, M. R. (2007). The Soul in the Brain: The Cerebral Basis of Language, Art, and Belief. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Edelman, G. M., & Tononi, G. (2000). A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination. Basic Books. Damasio, A. (2010). Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain. Pantheon.

Further Reading:

Atran, S. (2002). In Gods We Trust: The Evolutionary Landscape of Religion. Oxford University Press. Boyer, P. (2001). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. Basic Books. Geertz, A. W., & Markusson, G. I. (2010). Religion is natural, atheism is not: On why everybody is both right and wrong. Religion, 40(3), 152-165. Jaynes, J. (1976). The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Houghton Mifflin. McCauley, R. N. (2011). Why Religion is Natural and Science is Not. Oxford University Press. Schjoedt, U., Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H., Geertz, A. W., & Roepstorff, A. (2009). Highly religious participants recruit areas of social cognition in personal prayer. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4(2), 199-207. Whitehouse, H. (2004). Modes of Religiosity: A Cognitive Theory of Religious Transmission. AltaMira Press.

References:

Cavanna, A. E., & Trimble, M. R. (2006). The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain, 129(3), 564-583.

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and archetype. New York: Penguin Books.

Raichle, M. E., MacLeod, A. M., Snyder, A. Z., Powers, W. J., Gusnard, D. A., & Shulman, G. L. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 676-682.

Rappaport, M. J. (2020). Cognitive archaeology and the evolutionary origins of the human mind. New York: Springer.

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here.

0 Comments