The landscape of mental health is undergoing a quiet revolution that is moving us away from the chemical imbalance theories of the twentieth century and toward a profound new understanding of the physics of sentience. For years we have treated the mind as a flawed machine or a broken computer but new insights from computational neuroscience suggest we are something far more complex. We are a collection of biological imperatives and strategic layers playing a high stakes game of survival.

At the heart of this shift is the work of neuroscientist Karl Friston and his Free Energy Principle. While the mathematics are dense the implication for those of us living with trauma or treating it is simple and staggering. Our brains are not designed for truth. They are designed for survival. We are prediction machines that exist to minimize surprise and when that machinery breaks down during trauma we find ourselves trapped in a strategic deadlock that no amount of positive thinking can break.

This perspective transforms how we understand the “stuckness” of PTSD and anxiety. It suggests that the symptoms we fight against are not malfunctions but successful strategies employed by the deepest parts of our nervous system to keep us safe in a world it predicts is dangerous. To heal we must stop fighting these symptoms and start understanding the game our brain is playing so we can change the rules.

The Imperative of Existence

To understand why we suffer we must look at the most basic requirement of being alive. The universe tends toward chaos and entropy. If you leave a cup of coffee on a table it eventually goes cold and merges with the room’s temperature. It loses its distinctness. Living things resist this. We maintain our temperature and our boundaries and our internal order against the chaotic forces outside.

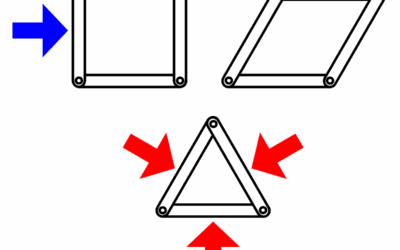

Friston argues that to do this we must minimize “free energy” which in this context is a measure of surprise. A fish is surprised to find itself on land because that state is incompatible with its survival. To exist the fish must minimize the likelihood of that state. We do this through two main mechanisms which Friston calls Active Inference. We can change our minds to fit the world which is perception or we can change the world to fit our minds which is action.

In a healthy mind these loops work seamlessly. We predict the world and when we are wrong we update our model or we act to fix the discrepancy. But trauma breaks this loop. When we face a threat we cannot escape or defeat our active inference fails. We cannot change the world because we are helpless and we cannot change our mind because the reality is too terrible to integrate. The result is a massive surge of prediction error—a chaotic energy that the brain must manage at any cost.

The Internal Game of Conflict

This is where the metaphor of Game Theory becomes illuminating for clinical practice. We often speak of “parts” in therapy but it is helpful to view the brain as a hierarchical organization of distinct players each with their own goals and strategies.

At the bottom is the Brainstem or the Enforcer. Its goal is immediate survival. It cares about heart rate and oxygen and adrenaline. It plays a game of life and death where the only losing move is to cease existing. It is extremely risk averse and operates on a hair trigger.

In the middle is the Limbic System or the Evaluator. It assesses value and social connection. It asks if things are good or bad and if we are loved or rejected. It manages our emotional economy.

At the top is the Neocortex or the Strategist. It deals in time and narrative and long term planning. It can simulate futures and imagine pasts. It creates the story of “I” that we identify with.

In a regulated nervous system these players cooperate. The Strategist makes a plan and the Enforcer provides the energy to execute it. But in trauma they turn against each other. The Enforcer perceives a threat that the Strategist says isn’t there. Or the Strategist tries to plan for a future that the Enforcer believes we won’t survive to see. The result is a Nash Equilibrium—a stalemate where no part of the brain can change its strategy without risking catastrophe.

The Problem of Cheap Talk

One of the most frustrating aspects of trauma therapy is the failure of logic. You can know intellectually that you are safe but still feel terrified. Game theory explains this through the concept of “cheap talk.”

In strategic scenarios words are often “cheap” because they cost nothing to produce. I can say “I am not afraid” while my hands are shaking. The Cortex is a master of cheap talk. It can generate endless rationalizations and affirmations. But the Brainstem and the Limbic system do not speak English. They speak the language of survival which relies on “costly signaling.”

A costly signal is something that is hard to fake. A racing heart and sweaty palms and a flooded nervous system are costly signals. They consume massive amounts of energy. Because they are expensive the deep brain trusts them more than it trusts the cheap words of the Cortex. This is why you cannot talk yourself out of a panic attack. Your Brainstem is receiving a high precision signal of danger from your body and it simply does not believe the low precision reassurances from your conscious mind.

Restoring the Strategic Self through Mechanism Design

If we view the traumatized brain as a game that is stuck in a bad equilibrium then therapy becomes a form of mechanism design. We are trying to create a new set of rules and incentives that allow the players to cooperate again.

This helps explain why somatic and experiential therapies like Brainspotting and Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT) are often more effective for deep trauma than talk therapy alone. These modalities do not rely on the cheap talk of the cortex. They intervene directly at the level of the Enforcer and the Evaluator.

When we use a technique like Brainspotting we are fixing the eyes on a specific point in space that correlates with internal distress. In game theory terms we are blocking the usual strategy of “looking away” or avoiding the pain. We are forcing the system to confront the mismatch between its internal prediction of danger and the external reality of safety. The client is staring at the spot where the “monster” lives but the monster is not attacking.

This creates a “glitch” in the predictive model. The Enforcer is screaming danger but the sensory data is reporting safety. Because the client cannot look away the brain is forced to update its model to resolve the conflict. It creates a new prediction: “I am safe now.” This is not a verbal belief but a biological update that releases the trapped energy of the survival response.

Implications for Clinical Practice

For us as clinicians this framework suggests a radical shift in how we approach our work. We must move beyond being listeners to being engineers of corrective experience. We are not just holding space we are active co-regulators in a biological game.

We need to recognize that when a patient is resistant or stuck they are not being difficult. They are playing a dominant strategy that has kept them alive. To ask them to just “let go” is to ask them to disarm in the middle of a war zone. We must respect the wisdom of their defenses while gently introducing new information that makes those defenses obsolete.

This means we must be fluent in the languages of all three layers. We need the narrative skills to engage the Cortex but we also need the somatic skills to speak to the Brainstem. We need to be comfortable with the silence and the intensity of deep processing work where the real change happens not in the exchange of words but in the reorganization of neural firing patterns.

Implications for Self Help and Personal Understanding

For those navigating their own healing journey this perspective offers a compassionate new way to view your symptoms. You are not broken. You are a highly tuned survival machine acting exactly as you were designed to act. Your anxiety and your shutdown and your hypervigilance are costly signals that your deep brain is sending to protect you.

The path to healing is not about fighting these parts of yourself. It is about learning to listen to them and then teaching them that the war is over. It involves finding ways to send costly signals of safety to your own nervous system. This might look like breathwork or grounding exercises or spending time in nature—activities that physically demonstrate to your Brainstem that you are safe enough to relax.

Recovery is the shift from a finite game of survival where the goal is just to make it to tomorrow to an infinite game of growth where the goal is to explore the possibilities of your own existence. It is the restoration of the “Strategic Self”—a mind that is no longer at war with itself but is integrated and free to engage with the beauty and complexity of the world.

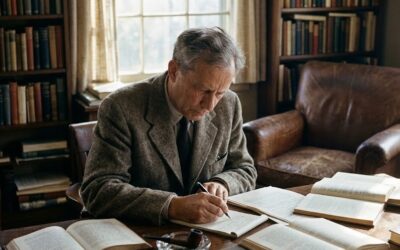

Biography of Karl Friston

Karl John Friston was born in York England in 1959 and has become one of the most influential figures in the history of neuroscience. His early academic journey began at Gonville and Caius College Cambridge where he studied natural sciences before completing his medical training at King’s College Hospital Medical School in London.

Friston’s career is marked by a dual legacy. In the 1990s he revolutionized the field of brain imaging by inventing Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM). Before Friston comparing brain scans was a subjective art. He brought rigorous statistical mathematics to the process allowing researchers to map functional activity in the brain with precision. This work alone would have secured his place in history as it became the standard for analyzing fMRI and PET data worldwide.

However his ambition went beyond measurement. He wanted to understand the fundamental principles of how the brain works. This led to his development of the Free Energy Principle a unified theory of brain function that integrates thermodynamics and evolutionary biology and information theory. Friston currently serves as a Professor of Neuroscience at University College London and is a Fellow of the Royal Society. He is often cited as one of the most likely future recipients of a Nobel Prize for his contributions to our understanding of the biological basis of the mind.

Timeline of Key Works

1991 – Introduction of Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) which provided the mathematical framework for modern neuroimaging.

1994 – Development of Voxel-Based Morphometry allowing for the analysis of brain anatomy differences.

2003 – Publication of key papers on Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) enabling researchers to understand how brain regions influence each other.

2005 – “A Theory of Cortical Responses” which began to articulate the predictive coding framework.

2010 – Publication of “The Free-Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory?” in Nature Reviews Neuroscience bringing his grand theory to a wider audience.

2017 – “Active Inference: A Process Theory” providing a biological blueprint for how living things minimize free energy through action and perception.

2019 – Exploration of the “Markov Blanket” concept applied to consciousness and self-organization.

Selected Bibliography

Friston K. J. et al. (1991). “Comparing functional (PET) images: The assessment of significant change.” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism.

Friston K. J. (2005). “A theory of cortical responses.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

Friston K. J. (2010). “The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?” Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

Friston K. J. (2013). “Life as we know it.” Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Friston K. J. et al. (2017). “Active inference: A process theory.” Neural Computation.

Influences and Legacy

Karl Friston’s intellectual lineage is vast and eclectic. He draws heavily from the work of Hermann von Helmholtz the 19th-century physicist and physician who first suggested that perception is a process of unconscious inference. Friston formalized Helmholtz’s intuition using modern statistical mechanics. He is also deeply influenced by Richard Feynman particularly in his use of variational calculus and path integrals which Friston adapted to explain how the brain optimizes its beliefs.

His legacy is already reshaping multiple fields. In Artificial Intelligence his work on Active Inference is providing an alternative to standard reinforcement learning offering a path toward more biological and adaptive AI. In philosophy his ideas are being used to bridge the gap between mind and matter offering a biophysical explanation for consciousness.

Most importantly for us his work is beginning to permeate clinical psychotherapy. His collaboration with figures like Mark Solms has helped birth the field of “Neuropsychoanalysis” validating the intuitions of Freud and Jung with the rigor of mathematics. Clinicians like Joel Blackstock and others in the somatic therapy community are now using Friston’s framework to explain why bottom-up therapies work creating a scientifically grounded model for the healing of the human spirit.

0 Comments