Read More on Jung here:

part 1: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-villain-with…nd-screenwriting/

part 2: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/using-jungian-ps…d-fiction-part-2/

part 3: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/applying-jungian…onality-theories/

Unveiling the Layers of the Self: Parts-Based Therapies in Psychotherapy and Fiction

Main Points and Key Ideas:

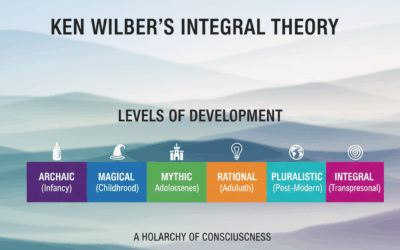

1. Parts-based therapies view the human psyche as composed of multiple sub-personalities or “parts,” each with its own perspective, emotions, and coping mechanisms.

2. Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy categorizes parts into exiles, managers, and firefighters, aiming to develop a compassionate relationship with these parts.

3. Voice Dialogue therapy focuses on identifying and dialoguing with different “selves” within the psyche to gain self-awareness and understanding.

4. The Jungian concept of the shadow represents repressed or denied aspects of ourselves that we find unacceptable.

5. Process-Oriented Psychology emphasizes exploring the underlying “process” of human experience, including subtle signals, sensations, and dreams.

6. These therapeutic approaches can be applied to character development in fiction writing to create more complex, authentic, and emotionally resonant characters.

7. Writers can use techniques such as identifying characters’ parts, exploring the origins and functions of these parts, and showing character growth through increased self-awareness.

8. Applying parts-based therapy concepts to dialogue can create more dynamic and psychologically rich exchanges between characters.

9. The integration of psychological insights into fiction writing can lead to more compelling storytelling and deeper connections with readers.

10. Various other parts-based therapy approaches, such as Psychosynthesis, Gestalt Therapy, and Emotion-Focused Therapy, offer additional tools for understanding and portraying complex characters.

Psychology as Character

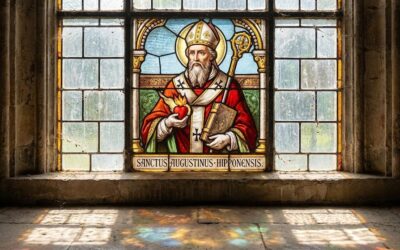

Understanding the Jungian Shadow:

At the heart of parts-based therapies lies the concept of the Jungian shadow. Schwartz, Perls, The Stones, Moreno, Hillman, Mindell and others all used Jung as a jumping off point for their parts based approaches. The shadow represents the repressed, denied, or disowned parts of ourselves that we find unacceptable or incompatible with our conscious self-image. These shadow elements are not inherently negative or evil, but rather represent the aspects of our being that we have learned to hide, suppress, or reject.

The shadow is formed through a complex interplay of developmental experiences, societal expectations, and personal beliefs. From a young age, we are bombarded with messages about who we should be, how we should behave, and what is considered acceptable or unacceptable. In an effort to conform to these external standards and gain approval from others, we often learn to silence or disown parts of ourselves that do not fit the mold.

However, the shadow does not simply disappear when we deny its existence. Instead, it continues to exert a powerful influence on our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors from the depths of our unconscious mind. It can manifest in various forms, such as self-sabotaging patterns, irrational fears, or projections onto others. Until we bring the shadow into conscious awareness and integrate it into our sense of self, it will continue to shape our lives in ways that may be detrimental to our well-being and relationships.

Parts Based Therapies that can be used for screenwriting and fiction:

Process Therapy:

Process-Oriented Psychology, also known as Process Work, developed by Arnold Mindell, offers valuable insights for creating compelling characters in fiction writing. This approach emphasizes the importance of exploring and unfolding the “process” that underlies human experience, including the subtle signals, sensations, and dreams that often go unnoticed or unexpressed. By attuning to these deeper dimensions of experience, writers can create characters that feel authentic, complex, and emotionally resonant.

Exploring Character Edges:

In Process Work, “edges” refer to the boundaries or limits of a person’s identity, beyond which lies unknown or unexpressed potential. By exploring a character’s edges—the places where they feel uncertain, uncomfortable, or resistant—writers can create opportunities for growth, conflict, and transformation. A character might have an edge around expressing vulnerability, for example, which could create interesting tensions and challenges as they navigate their relationships and goals.

Unfolding Character Dreams: Mindell’s approach recognizes the significance of dreams and their potential to reveal hidden aspects of the psyche. By exploring a character’s dreams, writers can gain insight into their unconscious desires, fears, and conflicts. A character’s recurring nightmare, for instance, might hold clues to unresolved traumas or repressed parts of their personality. By weaving these dream elements into the story, writers can create a sense of depth and mystery that compels readers to explore further.

Amplifying Character Signals:

Process Work encourages individuals to pay attention to the subtle signals and sensations that arise in their body and mind, as these can offer valuable information about their underlying process. For writers, this means attuning to the small details and gestures that reveal a character’s inner world. A character’s nervous tic, for example, might signal deeper anxieties or insecurities that shape their behavior and relationships. By amplifying these signals and exploring their significance, writers can create characters that feel nuanced and psychologically complex.

Embracing Character Polarities:

Mindell’s approach recognizes that human experience is often characterized by polarities or opposing tendencies, such as love and hate, strength and weakness, or creativity and destruction. By exploring the polarities within a character’s psyche, writers can create interesting tensions and paradoxes that drive their behavior and development. A character might struggle with the polarity of wanting to be successful and wanting to be liked, for instance, creating internal conflicts that shape their choices and relationships.

Facilitating Character Flirts: In Process Work, “flirts” refer to the subtle signals or impulses that arise at the edges of our experience, often pointing towards new possibilities or directions. By attuning to a character’s flirts—the fleeting thoughts, feelings, or intuitions that might otherwise be ignored or dismissed—writers can create opportunities for surprising developments and transformations. A character’s passing interest in a new hobby, for example, might signal a deeper longing for self-expression or adventure that could transform their life in unexpected ways.

Exploring Character Ghosts:

Mindell’s approach recognizes the influence of “ghosts” or unresolved figures from a person’s past that continue to shape their present experience. By exploring a character’s ghosts—the parents, siblings, or significant others who have left a lasting impact on their psyche—writers can create a sense of psychological depth and complexity. A character’s difficult relationship with their father, for instance, might create patterns of behavior or belief that shape their adult relationships and choices.

By incorporating these principles and techniques from Process-Oriented Psychology, writers can create characters that feel authentic, multi-dimensional, and emotionally compelling. Embracing the fluid and ever-unfolding nature of human experience, as emphasized in Process Work, writers can create characters that feel dynamic and alive, capable of surprising readers and themselves with their growth and transformation. Rather than presenting characters as fixed or static entities, this approach invites writers to explore the ways in which characters are constantly evolving in response to their inner and outer worlds, navigating the challenges and opportunities that arise along the way.

Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy:

One of the most well-known and widely practiced parts-based therapies is Internal Family Systems (IFS), developed by Richard Schwartz. IFS posits that our psyche is composed of various sub-personalities or “parts,” each with its own unique perspective, emotions, and coping mechanisms.

In IFS, these parts are broadly categorized into three main types: exiles, managers, and firefighters. Exiles represent the wounded, vulnerable, and often younger parts of ourselves that have been relegated to the shadows due to painful experiences or perceived inadequacies. Managers are the parts that strive to maintain control, order, and functionality in our lives, often by suppressing or distracting from the exiles. Firefighters are the reactive parts that emerge in times of crisis or overwhelming emotion, often engaging in impulsive or self-destructive behaviors to numb or escape the pain.

The goal of IFS therapy is to help individuals develop a compassionate and curious relationship with their different parts, learning to listen to their unique perspectives and needs. Through a process of “unblending” from identified parts and accessing the “Self,” a state of calm, clarity, and compassion, individuals can begin to heal the wounds of the exiles, negotiate with the managers, and transform the firefighters into more adaptive coping strategies.

IFS therapy emphasizes the importance of honoring and respecting all parts of the self, recognizing that even the most problematic or challenging parts have valuable insights and positive intentions. By fostering a sense of internal harmony and collaboration, IFS helps individuals develop greater self-leadership, resilience, and emotional well-being.

Applying Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy Techniques to Screenwriting and Fiction Writing:

Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy offers a rich framework for understanding the complex dynamics within the human psyche, and these insights can be invaluable for writers seeking to create lifelike, multi-dimensional characters. By applying IFS concepts and techniques to character development, writers can craft characters whose inner worlds are filled with conflicting motivations, desires, and fears, driving their actions and decisions in authentic, compelling ways.

Identifying Characters’ Parts:

One of the core techniques in IFS therapy is identifying and naming the different “parts” or sub-personalities within an individual’s psyche. These parts often have distinct roles, characteristics, and coping mechanisms that have developed in response to life experiences and relationships.

When developing characters, writers can use this technique to map out the different parts that comprise a character’s inner world. For example, a character might have a “Protector” part that seeks to keep them safe from emotional harm, a “Critic” part that drives them to achieve perfection, and a “Wounded Child” part that carries unresolved pain from their past.

By identifying and fleshing out these different parts, writers can create characters with rich, complex inner lives that extend beyond simple motivations or personality traits.

Exploring the Origins and Functions of Parts:

In IFS therapy, understanding the origins and functions of a person’s different parts is crucial for facilitating self-awareness and healing. Therapists work with clients to explore how their parts developed in response to specific experiences, relationships, or cultural contexts, and how these parts have served to protect or cope with challenges.

Writers can apply this technique to character development by delving into the backstories and formative experiences that have shaped their characters’ different parts. By understanding how a character’s “Protector” part emerged in response to early experiences of abandonment, or how their “Critic” part developed as a way to gain approval from a demanding parent, writers can create characters whose motivations and behaviors are grounded in authentic, relatable human experiences.

Creating Conflict Between Parts:

One of the key insights of IFS therapy is that an individual’s different parts can often be in conflict with one another, leading to internal struggles and contradictory behaviors. A person’s “Achiever” part, for example, might drive them to work tirelessly towards their goals, while their “Caregiver” part yearns for rest and connection with loved ones.

Writers can use this concept of conflicting parts to create compelling, lifelike characters whose inner worlds are filled with tension and struggle. By putting characters in situations that activate different parts of their psyche, writers can explore how these parts negotiate, compromise, or clash with one another, driving the character’s actions and decisions in complex, unpredictable ways.

For example, a character’s “Adventurer” part might impulsively accept a dangerous mission, while their “Responsible Parent” part tries to talk them out of it. As these parts battle for control, the character’s external journey takes shape, reflecting the rich, multi-layered nature of their inner world.

Showing Characters’ Growth Through Parts Work:

In IFS therapy, the goal is not to eliminate or suppress certain parts of the self, but rather to foster greater self-awareness, compassion, and integration. Therapists work with clients to develop a curious, accepting relationship with their different parts, allowing them to express their needs, fears, and desires in a safe, non-judgmental space.

Writers can mirror this process of growth and integration in their characters’ arcs, showing how they learn to recognize, understand, and embrace the different parts of their psyche. A character might begin their journey in a state of internal conflict, with their “Critic” part constantly berating them for their failures, and their “People-Pleaser” part driving them to sacrifice their own needs for others.

As the story unfolds, the character might encounter challenges or relationships that force them to confront and understand these parts of themselves. They might learn to set boundaries with their “People-Pleaser” part, or develop self-compassion in response to their “Critic” part. By showing characters’ growth through their relationship with their parts, writers can create arcs that feel authentic, emotionally resonant, and deeply satisfying.

Moving Beyond Plot and Pantsing:

By incorporating IFS concepts and techniques into character development, writers can move beyond the traditional dichotomy of “plotting” versus “pantsing” and instead focus on the organic unfolding of their characters’ inner worlds.

Rather than imposing external plot points or relying on spontaneous inspiration, writers can allow their characters’ conflicting parts and internal struggles to guide the story’s direction. As characters navigate the tensions between their different parts, their choices and actions emerge naturally, creating a sense of authenticity and inevitability in the narrative.

This approach to character-driven storytelling requires a deep understanding of each character’s unique configuration of parts, their origins, and their complex interplay. By investing time and effort into developing characters’ inner worlds through the lens of IFS therapy, writers can create stories that feel alive, unpredictable, and emotionally impactful.

When creating characters, drawing inspiration from parts-based therapies like Internal Family Systems (IFS), Voice Dialogue, and Process Therapy can be incredibly beneficial. These therapeutic approaches view the human psyche as a complex system of distinct parts or subpersonalities, each with its own unique traits, motivations, and roles. By applying this concept to character development, writers can create nuanced, realistic characters that feel neither archetypal nor over-planned, while also avoiding extraneous, unplanned details or unnecessary arcs.

By conceptualizing characters as a system of interconnected parts, writers can delve deep into their characters’ inner worlds, exploring the interplay between their various subpersonalities. This approach allows for a rich understanding of how different aspects of a character’s psyche influence their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in any given situation. As a result, characters become more authentic, three-dimensional, and consistent throughout the story.

Integrating parts-based therapy concepts into character development offers advantages for both plotters and pantsers. Plotters, who prefer to outline and plan their stories in advance, can use their understanding of character parts to map out realistic arcs and plot points that align with the characters’ psychological makeup. By considering how events will impact different subpersonalities and how those parts might respond, plotters can construct a coherent and compelling plot that feels true to the characters.

On the other hand, pantsers, who prefer to discover the story as they write without extensive outlining, can use their intuitive understanding of character parts to organically develop the story. By tapping into the unique dynamics between subpersonalities, pantsers can allow the characters to guide the story, ensuring that their actions and reactions feel authentic and unforced. This approach helps pantsers maintain a balance between character-driven storytelling and plot progression, minimizing the risk of including extraneous details or unnecessary arcs.

Regardless of whether a writer is a plotter or a pantser, investing time in building characters using insights from parts-based therapies can lead to the creation of believable, engaging characters that drive the story forward. By striking a balance between the characters’ inner complexities and the demands of the plot, writers can craft stories that resonate with readers on a deep, psychological level.

Voice Dialogue Therapy:

Another influential parts-based therapy is Voice Dialogue, developed by Hal and Sidra Stone. Voice Dialogue focuses on the concept of “selves” or sub-personalities that operate within our psyche, each with its own unique perspective, desires, and fears.

In Voice Dialogue, the therapist facilitates a process of “dialoguing” with these different selves, allowing them to express themselves and be heard. By giving voice to the various parts of the self, individuals can gain a deeper understanding of their internal dynamics, conflicts, and patterns of behavior.

Some of the common selves explored in Voice Dialogue include the Inner Critic, the Pleaser, the Perfectionist, the Rebel, and the Vulnerable Child. Each of these selves plays a specific role in our overall functioning, often developed in response to early life experiences and relationships.

Through the process of Voice Dialogue, individuals learn to recognize and differentiate between their various selves, developing a greater sense of self-awareness and choice. By embracing the multiplicity of the self and fostering a sense of inner dialogue and collaboration, Voice Dialogue helps individuals navigate the complexities of their internal world with greater ease and authenticity.

Voice Dialogue Sub Personalities:

Voice dialogue therapy uses several parts the Sidra and Hal Stone call “sub personalities”

The Inner Critic:

One of the most pervasive and influential parts of the self is the Inner Critic. The Inner Critic is the internalized voice of judgment, self-doubt, and self-blame that often plagues our thoughts and undermines our sense of self-worth.

The origins of the Inner Critic can often be traced back to early childhood experiences, where we may have internalized the critical or demanding voices of caregivers, authority figures, or societal expectations. Over time, this internal voice becomes a constant companion, monitoring our every move and finding fault with our actions, appearance, or achievements.

In parts-based therapies, the goal is not to silence or eliminate the Inner Critic, but rather to understand its origins, motivations, and impact on our lives. By developing a compassionate and curious relationship with the Inner Critic, we can begin to challenge its assumptions, reframe its messages, and cultivate a more balanced and supportive internal dialogue.

The Pusher:

Another common part of the self is the Pusher, the driving force behind our ambition, productivity, and achievement. The Pusher is the part of us that strives for success, sets high standards, and pushes us to excel in various areas of life.

While the Pusher can be a valuable source of motivation and determination, it can also become overactive or imbalanced, leading to burnout, perfectionism, or a relentless sense of never being good enough. When the Pusher is in overdrive, it can drown out the needs and desires of other parts of the self, leaving us feeling disconnected, exhausted, or unfulfilled.

In parts-based therapies, individuals learn to recognize the presence and impact of the Pusher, exploring its origins and the underlying fears or beliefs that fuel its intensity. By developing a more balanced relationship with the Pusher, individuals can harness its energy and focus in a more sustainable and self-compassionate way, allowing space for rest, play, and self-care.

The Pleaser:

The Pleaser is the part of the self that seeks approval, validation, and harmony in relationships. It is the part that strives to meet the needs and expectations of others, often at the expense of one’s own desires or boundaries.

The Pleaser often develops in response to early experiences of conditional love or acceptance, where a child learns that their worth is contingent upon pleasing others or conforming to external standards. Over time, this pattern of self-abandonment can lead to a sense of disconnection from one’s authentic self, as well as difficulties with assertiveness, self-advocacy, and intimacy.

In parts-based therapies, individuals explore the origins and impact of the Pleaser, learning to recognize its presence and the ways in which it shapes their interactions and relationships. By developing a more authentic and self-honoring relationship with the Pleaser, individuals can begin to set healthy boundaries, communicate their needs and desires, and cultivate more fulfilling and reciprocal connections with others.

Traumatized Parts:

Trauma can have a profound impact on the psyche, often leading to the development of specific parts or sub-personalities that carry the wounds and adaptations related to the traumatic experience. In parts-based therapies, these traumatized parts are often referred to as “exiles” or “wounded parts.”

Traumatized parts often hold the painful emotions, memories, and beliefs associated with the traumatic event, such as fear, shame, guilt, or helplessness. These parts may have become isolated or disconnected from the rest of the self as a way of coping with the overwhelming nature of the trauma.

In therapy, the goal is to create a safe and compassionate space for these traumatized parts to be seen, heard, and validated. Through a process of gentle exploration and “witnessing,” individuals can begin to access the wounded parts of themselves, providing them with the care, understanding, and support they need to heal.

This process often involves a careful navigation of the individual’s “window of tolerance,” ensuring that the exploration of traumatic material occurs at a pace and intensity that feels manageable and non-retraumatizing. Through the integration of traumatized parts, individuals can begin to release the grip of the past, reclaim a sense of wholeness and agency, and move forward in their lives with greater resilience and self-compassion.

The Vulnerable Child:

At the core of many parts-based therapies lies the recognition of the Vulnerable Child, the part of the self that holds the earliest experiences of vulnerability, need, and dependency. The Vulnerable Child is the part of us that longs for love, safety, and belonging, and that carries the wounds of early experiences of neglect, abandonment, or insecurity.

In many individuals, the Vulnerable Child becomes buried or suppressed as a way of coping with the pain and uncertainty of early life experiences. We may develop protective parts or strategies to keep the Vulnerable Child hidden, such as the Pusher, the Pleaser, or the Inner Critic.

However, the Vulnerable Child remains a vital part of our authentic self, holding the key to our deepest longings, fears, and needs. In parts-based therapies, individuals learn to develop a compassionate and nurturing relationship with the Vulnerable Child, providing it with the care, validation, and support it may have lacked in early life.

By connecting with the Vulnerable Child and honoring its needs and feelings, individuals can begin to heal the wounds of the past, develop a greater sense of self-acceptance and self-love, and cultivate more authentic and fulfilling relationships with others.

Using Voice Dialogue Techniques in Screenwriting and Fiction:

Voice Dialogue, a therapeutic approach developed by Drs. Hal and Sidra Stone, offers a powerful framework for understanding the various subpersonalities or “selves” that comprise the human psyche. By applying the principles and techniques of Voice Dialogue to character development, writers can create complex, multi-dimensional characters that feel authentic, relatable, and emotionally resonant.

Identifying Characters’ Selves:

At the core of Voice Dialogue is the concept that our psyche is composed of multiple selves or subpersonalities, each with its own unique perspective, desires, and fears. These selves often develop in response to early life experiences, relationships, and societal expectations, and they can be both beneficial and limiting in their influence on our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

When developing characters, writers can use this concept of selves to map out the different subpersonalities that comprise a character’s inner world. For example, a character might have a “Responsible Self” that drives them to excel in their career, a “Rebellious Self” that yearns for freedom and adventure, and a “Vulnerable Child Self” that carries unresolved wounds from their past.

By identifying and fleshing out these different selves, writers can create characters with rich, complex inner lives that extend beyond simple motivations or personality traits.

Giving Voice to Characters’ Selves:

In Voice Dialogue therapy, the process of “dialoguing” with different selves is crucial for developing self-awareness and understanding. Therapists guide clients in giving voice to their various selves, allowing each subpersonality to express its unique perspective, needs, and concerns.

Writers can apply this technique to character development by creating scenes or passages that give voice to a character’s different selves. This can be done through internal monologue, dialogue with other characters, or even through creative writing exercises where the writer embodies each of the character’s selves and writes from their perspective.

By allowing characters’ selves to speak and be heard, writers can explore the nuances and contradictions within their inner worlds, creating a sense of depth and authenticity in their portrayal.

Exploring the Relationships Between Selves:

In Voice Dialogue, understanding the relationships and dynamics between different selves is key to fostering integration and wholeness within the psyche. Some selves may work in harmony with one another, while others may be in conflict or opposition.

Writers can use this concept to create compelling inner conflicts and tensions within their characters. For example, a character’s “Perfectionist Self” might constantly criticize and undermine their “Creative Self,” leading to self-doubt and creative blocks. Or a character’s “Caregiver Self” might be in constant tension with their “Self-Nurturing Self,” leading to burnout and neglect of their own needs.

By exploring the relationships and power dynamics between characters’ selves, writers can create complex, multi-layered inner worlds that drive their characters’ actions, choices, and growth in compelling ways.

Showing Characters’ Growth Through Self-Awareness:

In Voice Dialogue therapy, the goal is not to eliminate or suppress certain selves, but rather to develop a greater sense of self-awareness and choice in how we relate to and express these different aspects of ourselves. By giving voice to and understanding their different selves, individuals can learn to embrace their complexity and make more conscious, authentic choices in their lives.

Writers can mirror this process of growth and self-awareness in their characters’ arcs, showing how they learn to recognize, understand, and integrate the different selves within their psyche. A character might begin their journey feeling torn between their “Responsible Self” and their “Adventurous Self,” leading to inner conflict and a sense of being stuck.

As the story unfolds, the character might encounter experiences or relationships that help them to give voice to and understand these different selves. They might learn to find a balance between responsibility and adventure, or to embrace their complexity and make choices that honor both selves. By showing characters’ growth through their relationship with their selves, writers can create arcs that feel authentic, emotionally resonant, and transformative.

Enhancing Character Interactions and Dialogue:

Voice Dialogue not only illuminates the inner world of individual characters but also provides a framework for understanding the complex dynamics between characters. Each character’s unique configuration of selves can influence how they perceive, relate to, and communicate with others.

Writers can use this understanding to create rich, layered interactions and dialogue between characters. For example, a scene between two characters might be shaped by the interplay of their respective “Controlling Selves,” each vying for dominance and authority. Or a moment of vulnerability might arise when one character’s “Wounded Child Self” resonates with and draws out the “Nurturing Parent Self” in another.

By considering the selves that are active within each character during a given interaction, writers can craft exchanges that feel authentic, charged, and revelatory, illuminating the complex web of desires, fears, and power dynamics that underlie human relationships.

Using Dreams in Voice Dialogue:

Sidra and Hal Stone’s concept of dreams in parts therapy can also be used to show moments of growth and change for characters in fiction.

Identifying selves:

The Stones believe that dreams can reveal the various selves or subpersonalities within an individual’s psyche. They encourage exploring dream characters and their roles to gain insight into the dreamer’s inner world.

Giving voice to selves:

By dialoguing with dream characters, the dreamer can give voice to the different selves that emerge in their dreams. This process can help the dreamer understand the perspectives, needs, and concerns of these selves.

Exploring relationships between selves:

Dreams often depict interactions or conflicts between different characters, which can represent the relationships between the dreamer’s selves. Analyzing these dream interactions can provide insight into the power dynamics and tensions within the psyche.

Accessing vulnerability:

The Stones believe that dreams can provide a gateway to the dreamer’s vulnerable, unconscious selves. By exploring dreams with compassion and curiosity, the dreamer can connect with and understand these hidden aspects of themselves.

Confronting disowned selves:

Dreams may feature characters or scenarios that the dreamer finds uncomfortable, frightening, or repulsive. These elements can represent disowned or shadow selves that the dreamer has rejected or suppressed. Engaging with these selves through dream work can facilitate integration and wholeness.

Receiving guidance:

The Stones view dreams as a source of inner wisdom and guidance. By dialoguing with dream characters and exploring dream symbols, the dreamer can access insights and solutions that their conscious mind may have overlooked.

Tracking growth and change:

As an individual progresses in their personal growth and self-awareness, their dreams may reflect these changes. The Stones encourage paying attention to shifts in dream content and tone as indicators of the dreamer’s evolving relationship with their selves.

Enhancing creativity:

Dreams can be a rich source of creative inspiration. The Stones suggest exploring dream imagery and narratives to unlock new ideas, perspectives, and possibilities in the dreamer’s waking life.

Facilitating self-care:

Dreams may highlight areas where the dreamer needs to practice greater self-care or self-compassion. By attending to the messages and needs expressed by dream characters, the dreamer can learn to nurture and support their various selves.

Strengthening the Aware Ego:

The ultimate goal of Voice Dialogue is to develop the Aware Ego, a centered, compassionate aspect of the self that can observe and facilitate communication between the various selves. By working with dreams, the dreamer can strengthen their Aware Ego and foster greater self-awareness and integration.

Applying Parts-Based Therapies in Fiction Writing:

Techniques and Structures for Using Jungian Psychology and Parts-Based Therapy in Character Development

Shadow Confrontation:

Create situations that force characters to confront their Jungian shadow, the repressed or denied aspects of their psyche. This can lead to surprising actions, decisions, or revelations that deepen the character’s complexity and drive the story forward.

Parts-Based Conflict:

Utilize the concept of “parts” or sub-personalities from IFS and Voice Dialogue to create internal conflicts within characters. As different parts of the character’s psyche, such as the Inner Critic, Pleaser, or Protector, vie for control, the character’s behavior and motivations become more nuanced and unpredictable.

Trauma Triggers:

Explore how traumatic experiences shape characters’ psyches and create wounded or exiled parts. By placing characters in situations that trigger their traumatic wounds, writers can reveal hidden depths, vulnerabilities, and strengths that might otherwise remain unseen.

Shadow Projection:

Have characters project their own repressed qualities or desires onto others, leading to complex relationships and interactions. As characters recognize aspects of themselves in others, they may form surprising connections or experience unexpected conflicts.

Parts-Based Alliances:

Create situations where characters with seemingly opposing traits or backgrounds find common ground through shared parts or experiences. For example, two characters who appear vastly different on the surface might connect through their shared experience of childhood trauma or their mutual struggle with perfectionism.

Inner Dialogue:

Use inner dialogue or stream of consciousness writing to reveal the interplay between a character’s different parts or voices. By showcasing the internal negotiations, conflicts, and compromises between these parts, writers can create a rich and dynamic inner world for their characters.

Shadow Integration:

Show characters’ growth and transformation through the integration of their shadow aspects. As characters learn to accept and embrace their repressed qualities, they may exhibit surprising strengths, insights, or abilities that shift the course of the story.

Conceiving Character Dialogue Using Parts-Based Interactions:

When crafting dialogue between characters, writers can use the concept of parts-based interactions to create more dynamic, layered, and psychologically rich exchanges. By considering which part of each character is speaking and to which part of the other character they are responding, writers can infuse their dialogue with subtext, tension, and emotional resonance.

For example, imagine a scene where two characters, A and B, are arguing about a decision that needs to be made. Character A’s Pleaser part might be speaking, trying to appease and accommodate Character B to avoid conflict. Meanwhile, Character B’s Inner Critic part might be responding, expressing doubt, judgment, or disapproval towards Character A’s suggestions.

By recognizing the specific parts that are interacting, writers can create dialogue that feels authentic, charged, and revelatory. The Pleaser part of Character A might express sentiments like, “I just want us to find a solution that works for everyone,” or “I’m willing to compromise if it means we can move forward.” The Inner Critic part of Character B might retort with lines like, “You’re not thinking this through,” or “We can’t just settle for any decision because you’re afraid of rocking the boat.”

As the conversation progresses, the parts being expressed might shift, revealing new layers of the characters’ psyches and relationships. Character A’s Assertive part might emerge, standing up for their needs and desires, while Character B’s Vulnerable Child part might surface, expressing fears or insecurities that underlie their critical stance.

By attuning to the parts-based interactions within dialogue, writers can create exchanges that are not only more emotionally compelling but also more revealing of the characters’ inner worlds, conflicts, and growth. Readers will recognize the authentic, multi-faceted nature of these interactions, as they mirror the complex interplay of parts within their own relationships and conversations.

Moreover, by tracking which parts of each character are speaking and being spoken to throughout the story, writers can create satisfying arcs of growth, healing, and transformation. As characters learn to recognize and integrate their different parts, their dialogues will reflect this evolution, with more self-aware, compassionate, and authentic exchanges that showcase their psychological depth and development.

The concept of “parts” or sub-personalities within the self, as used in parts-based therapies, provides a powerful tool for understanding and portraying the complex inner world of characters. Recognizing that characters, like real people, possess different aspects of their personality, such as the Inner Critic, the Pusher, or traumatized parts, allows writers to craft rich and dynamic inner monologues, conflicts, and behavioral patterns that bring their characters to life on the page.

Tracing the origins and functions of these parts back to characters’ early life experiences and relationships adds another layer of psychological depth and consistency to their portrayal. For instance, a character with a strong sense of humor may have developed this trait as a coping mechanism in response to feelings of shame, rejection, or the need to communicate difficult truths in a more palatable way. By understanding the roots of characters’ personality traits and coping styles, writers can create compelling and believable characters that resonate with readers.

Furthermore, the Jungian concept of the Shadow serves as a valuable tool for creating character depth and driving plot development. By exploring what information or aspects of themselves characters cannot acknowledge due to conflicts with their self-image, writers can create internal tensions, blind spots, and opportunities for growth and transformation that propel the story forward and keep readers engaged.

Ultimately, by drawing on these psychological concepts and tools, writers can craft characters that feel vivid, authentic, and emotionally resonant. Understanding the complex interplay of childhood experiences, personality parts, coping mechanisms, and the shadow enables writers to break through creative blocks and craft stories that explore the profound depths of the human experience.

The psychology of character is a rich and fascinating area with endless possibilities for exploration and application in fiction writing. By continuing to study and integrate psychological insights into their craft, authors can create stories that not only entertain but also illuminate the intricate complexities of the human psyche, forging deeper connections with readers and leaving a lasting impact on their audience.

Further Reading

Here are more parts based therapy approaches that might help you write compelling characters:

Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy:

Developed by Richard Schwartz, IFS posits that our psyche is composed of various sub-personalities or “parts,” each with its own unique qualities, desires, and beliefs. IFS recognizes the existence of the “Self,” a core essence that embodies compassion, clarity, and wisdom. The goal of IFS is to help individuals develop a harmonious relationship between their parts, integrating exiled or shadow aspects of the self to achieve greater wholeness and well-being.

Voice Dialogue:

Created by Hal and Sidra Stone, Voice Dialogue is a therapeutic approach that involves directly engaging with the various sub-personalities or “selves” within an individual’s psyche. Through a process of “dialoguing” with these selves, individuals can gain insight into their inner dynamics, conflicts, and potentials. Voice Dialogue recognizes the existence of disowned or shadow selves, which are often relegated to the unconscious mind, and seeks to integrate these aspects into a more balanced and authentic sense of self.

Psychosynthesis:

Developed by Roberto Assagioli, Psychosynthesis is an integrative approach that recognizes the existence of various sub-personalities within the psyche, as well as a higher, transpersonal self. Psychosynthesis aims to facilitate the integration and harmonization of these various aspects of the self, including the shadow, to achieve greater wholeness, purpose, and spiritual awakening.

Gestalt Therapy: Founded by Fritz Perls, Gestalt Therapy emphasizes the importance of present-moment awareness, direct experience, and the integration of various aspects of the self. Gestalt Therapy recognizes the existence of “polarities” within the psyche, which can include the persona and the shadow. Through techniques such as the “empty chair” dialogue, individuals can explore and integrate these polarities, leading to greater self-awareness and authenticity.

Jungian Active Imagination:

Active Imagination is a technique developed by Carl Jung that involves engaging with the unconscious mind through creative expression, such as writing, drawing, or painting. By dialoguing with the images, characters, and symbols that emerge from the unconscious, individuals can gain insight into their shadow aspects, complexes, and archetypal patterns. Active Imagination can facilitate the integration of the shadow and other unconscious contents into conscious awareness.

Psychodrama:

Created by Jacob L. Moreno, Psychodrama is an experiential approach that involves using dramatic action and role-playing to explore and resolve psychological conflicts. Participants enact scenes from their lives, often exploring different aspects of their personality, including shadow elements. Through this process, individuals can gain new perspectives, develop empathy, and integrate disowned parts of themselves.

Focusing:

Developed by Eugene Gendlin, Focusing is a body-oriented approach that involves tuning into one’s inner experience and “felt sense” of a situation or issue. By bringing a curious, non-judgmental attention to the bodily felt experience, individuals can access unconscious or shadow aspects of themselves, gaining insight and facilitating emotional healing.

Hakomi Therapy:

Founded by Ron Kurtz, Hakomi Therapy is a mindfulness-based, somatic approach that emphasizes the importance of present-moment experience and the exploration of unconscious beliefs and patterns. Hakomi recognizes the existence of “child states” or sub-personalities that hold these unconscious patterns, which can include shadow elements. Through a process of mindful self-study and experimentation, individuals can bring these patterns into conscious awareness and facilitate their transformation.

Archetypal Psychology:

Developed by James Hillman, Archetypal Psychology is an approach that emphasizes the importance of the imagination and the exploration of archetypal patterns and images in the psyche. Hillman’s work builds upon Jung’s concept of the shadow, recognizing the importance of integrating and honoring the darker, more neglected aspects of the self. Archetypal Psychology encourages individuals to engage with the mythic and symbolic dimensions of their experience, fostering a deepened sense of meaning and purpose.

Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT):

Founded by Leslie Greenberg, EFT is an experiential approach that emphasizes the importance of accessing, processing, and transforming emotional experiences. EFT recognizes the existence of different “parts” or “voices” within the self, which can include the shadow or disowned aspects of the personality. Through techniques such as chair work and focusing, individuals can develop a more accepting and compassionate relationship with these parts, facilitating emotional healing and integration.

part 1: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-villain-with…nd-screenwriting/

part 2: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/using-jungian-ps…d-fiction-part-2/

part 3: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/applying-jungian…onality-theories/

Did you like this article? Check out the podcast: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

https://www.podbean.com/ew/pb-f58dg-159e6b5

Bibliography:

- Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon Books.

- Freud, S. (Various works on psychoanalytic theory)

- Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

- Schwartz, R. C. (1995). Internal Family Systems Therapy. Guilford Press.

- Stone, H. & Stone, S. (1989). Embracing Our Selves: The Voice Dialogue Manual. New World Library.

- Mindell, A. (1985). River’s Way: The Process Science of the Dreambody. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

Further Reading:

- Assagioli, R. (1965). Psychosynthesis: A Manual of Principles and Techniques. Hobbs, Dorman & Company.

- Perls, F. (1969). Gestalt Therapy Verbatim. Real People Press.

- Moreno, J. L. (1946). Psychodrama. Beacon House.

- Gendlin, E. T. (1978). Focusing. Everest House.

- Kurtz, R. (1990). Body-Centered Psychotherapy: The Hakomi Method. LifeRhythm.

- Greenberg, L. S. (2002). Emotion-Focused Therapy: Coaching Clients to Work Through Their Feelings. American Psychological Association.

- McAdams, D. P. (1993). The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self. Guilford Press.

- von Franz, M. L. (1974). Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales. Spring Publications.

- Pearson, C. S. (1991). Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World. HarperOne.

- Johnson, R. A. (1991). Owning Your Own Shadow: Understanding the Dark Side of the Psyche. HarperOne.

0 Comments