The Symbolism of Eden: Language, Consciousness and the Birth of the Ego

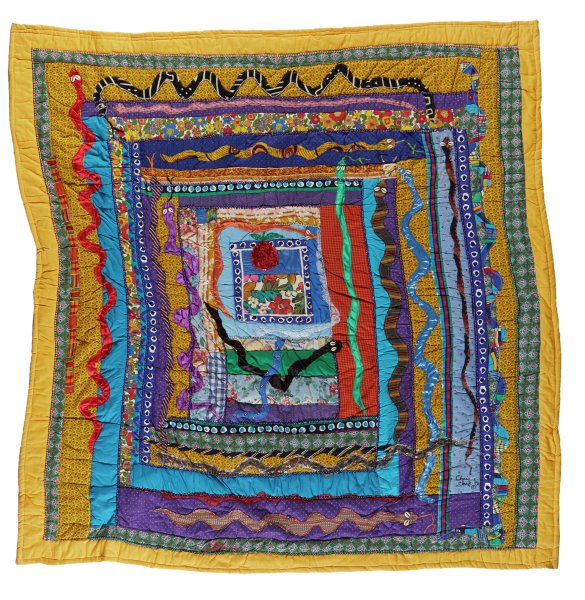

Garden of Eden Quilt from The Birmingham Museum of Art

The story of the Garden of Eden, found in the opening chapters of Genesis, is one of the most well-known and influential myths in human history. On the surface, it describes the idyllic life of the first humans, their temptation by the serpent to eat the forbidden fruit, and their subsequent exile from paradise as punishment. Yet this simple narrative is laden with profound symbolic meanings that have been pondered by theologians, philosophers, artists and mystics for centuries.

In particular, the Eden story can be understood as a mythological depiction of the birth of human consciousness, language and individuality out of the primordial unconscious. Through the lens of depth psychology, the figures of Adam, Eve, the serpent and the Garden can be seen as representing different aspects of the psyche and stages in psychological development. The “fall” into self-consciousness is imaged as expulsion from the Garden, marking the formation of the individual ego and its separation from instinctual, unconscious wholeness.

This paper will explore the symbolic meanings of the Eden narrative in dialogue with key ideas from depth psychology and cultural anthropology. Drawing especially on the work of psychologists Erich Neumann and Edward Edinger, it will argue that the story reflects universal patterns in the development of the individual psyche as well as the collective evolution of human consciousness and culture. The paper aims to show the enduring relevance of this ancient myth for illuminating the structure of the human mind, the origins of our capacity for self-awareness and volition, and the religious impulse toward reunion with our lost primordial origins.

The Symbolism of Eden_ Language, Consciousness and the Birth of the Ego

The Eden Story as Psychological Myth

The Eden narrative has often been interpreted in purely theological terms as an account of the first sin and the corruption of human nature. But the psychoanalytic tradition beginning with Freud and Jung has read religious stories as symbolic expressions of psychological realities. From this perspective, the Eden story is not just about an event in the distant past but about something that happens in the depths of every individual psyche. It reflects, in mythic form, a universal process of psychological development and individuation.

The figures in the story represent different structures or stages of consciousness. Before the fall, Adam and Eve symbolize the primordial human psyche in its original undifferentiated state of unconscious wholeness. The two are not yet fully distinct individuals but exist in a unified “participation mystique” with each other and nature. They live in the paradisiacal Garden, which represents the timeless, pre-egoic state of the psyche in harmony with the instincts and the organic world.

The central tree in the Garden symbolizes the axis mundi or world-center around which the primal state of psychic unity is organized. The serpent coiled around the tree represents the nascent stirrings of self-awareness, the capacity for reflection, discrimination and choice. Its temptation of Eve to eat the forbidden fruit signifies the emergence of the individual ego out of the collective psyche. Eve’s eating of the fruit and sharing it with Adam represents the “birth” of self-, the dawn of the ability to view oneself as an “I” separate from the world and others.

This eating of the fruit brought the “knowledge of good and evil.” Psychologically, this means that self-awareness inevitably entails discrimination, the capacity to experience opposites like subject and object, self and other, inside and outside. The ego’s ability to make judgments and choose between opposites is imaged as God’s pronouncement that humans have “become like one of us, knowing good and evil.” But this knowledge acquired through the birth of the ego is inseparable from a new sense of separateness and vulnerability. The ego is expelled from the Garden, representing its expulsion from unconscious wholeness into the world of time, space and mortality.

The Psychological Evolution from Unconscious Unity to Ego Consciousness

The Eden story, read psychologically, reflects the basic arc of individual psychological development as well as the collective evolution of human consciousness. This evolutionary arc was explored in depth by the psychologist Erich Neumann in his landmark work The Origins and History of Consciousness (1949). Neumann argues that the human psyche emerged out of a primordial state of undifferentiated unity he calls uroboros, named after the mythological serpent that eats its own tail. In the uroboros state, which characterizes the mentality of many animals and human infants, the subject is not yet distinct from the object, the psyche not yet separate from the world. There are no clear ego boundaries.

Over the course of evolution, this original participation mystique was gradually superseded by a process of individuation and ego development. As the human brain grew more complex through natural selection, cognitive faculties like memory, language, tool use and abstract thinking emerged. The psyche became increasingly differentiated, with competing impulses, drives and mental systems. A central regulatory system – an ego – had to develop to mediate among these different psychic contents and choose which impulses to act upon or repress.

The growth of the ego allowed humans to separate themselves from the instinctual unconscious and develop a degree of autonomy and self-control. But it came at the price of a certain separation from the body, nature and the primordial Ground of being. Self-consciousness inevitably structured reality in terms of opposites – self and other, good and bad, known and unknown. This created an experience of lack and existential insecurity. The ego could never encompass the totality of the psyche and instead had to define itself in opposition to the unconscious. The result was a sense of division and alienation.

Neumann saw evidence for this psychological evolution in the mythologies of ancient cultures. He argued that myths like the Eden story encoded the birth of consciousness out of the unconscious in symbolic form. Creation myths involving a primal act of division or sacrifice, like Marduk’s slaying of the mother goddess Tiamat in Babylonian myth, reflected the ego’s separation from the “Great Mother” of the unconscious. The ubiquitous mythological motif of the hero’s journey, in which an individual leaves home on a quest and returns with new self-knowledge, was an image of the ego’s development and individuation.

Neumann identified different stages of this evolution of consciousness which recapitulated the psychological development of the individual. In the “matriarchal” stage, characteristic of indigenous cultures, the ego was only weakly developed and existed in a childlike dependence on the Great Mother of the unconscious. The “patriarchal” stage, emerging in the first civilizations, involved the ascendancy of the masculine ego and its heroic struggle to separate from the unconscious through abstract thought and willpower. Finally, the “integral” stage, which was still to be fully realized, would involve a higher integration of ego and unconscious, thinking and feeling, in a new synthesis.

The Mythological Motif of the World Center and the Birth of Consciousness

The Eden narrative and its parallels in other cultures reflect this evolution of consciousness in mythic form. A key symbolic element in these stories is the image of the “world center” or axis mundi around which the primordial psyche is organized. This is represented in the Eden story by the central tree in the midst of the Garden. The tree is the connecting axis between heaven and earth, an image of the original non-duality of spirit and nature, psyche and matter.

This primal center is typically depicted as a mandala, a circular image with a sacred center and four surrounding directions or rivers. In the Eden story, four rivers are said to flow out of the Garden, representing the four cardinal directions and the extension of the primordial psyche out into the world. The world-center mandala can be found in art and iconography across cultures, from Hindu yantras and Buddhist mandalas to Christian depictions of the Heavenly Jerusalem with Christ at the center. It reflects an archetypal, transpersonal image of psychic wholeness.

The psychologist Edward Edinger, in his book The Creation of Consciousness (1984), explored how this mandala motif reflects the birth of the ego out of the unconscious. Examining art made spontaneously by patients in therapy, Edinger noticed the recurrence of mandala-like images, often with a central circle surrounded by a square or four symmetrical figures. He connected this to the “quadrated circle” of medieval alchemy, which symbolized the union of spirit and matter, as well as to the four rivers of Eden and to the four gospels arrayed around Christ in Christian tradition. For Edinger, the fourfold mandala was an archetypal image of the Self, the central organizing principle of the psyche.

Edinger argued that the spontaneous production of mandala imagery in both individual art and cultural symbolism reflected the birth of the ego out of the Self. The circular totality of the mandala represented the primordial unconscious before the dawn of the ego. As the ego began to emerge as a separate center of consciousness, the mandala was divided into four, with a cross or quaternity now organizing it. This division into four represented the ego’s nascent ability to discriminate among different psychic contents and to see itself as separate from the world and the unconscious. The four rivers flowing out of Eden express this extension of the psyche into the field of space-time.

But the emergence of the ego as a distinct unit within the mandala was experienced as a loss of primal wholeness, a rupture of the original unity of Self. The biblical expulsion from Eden symbolized this fall into alienation. In psychological terms, the ego now experienced itself as incomplete and divided, cut off from the nourishing waters of the unconscious. The fourfold structure of consciousness (thinking, feeling, sensation, intuition) now stood in opposition to the unconscious. The developmental goal now was to reintegrate the four functions around a central Self, repairing the rupture to create a mandala of higher consciousness.

The Rise of the Hero and the Separation from the Great Mother

The emergence of the ego and its heroic separation from the unconscious can also be discerned in the mythic trope of the hero’s battle with a dragon or monster, which represents the Great Mother of the primordial psyche. An example is the Babylonian hero Marduk’s defeat of the mother goddess Tiamat, or the Greek hero Apollo’s slaying of the earth-serpent Python. These myths symbolize the nascent ego’s struggle to differentiate itself from the engulfing powers of the unconscious and to establish its autonomy.

In the Eden story, the maternal unconscious takes the form of the serpent, who tempts Eve to eat from the tree of knowledge. On a psychological level, the serpent symbolizes the seductive allure of the unconscious, the temptation to remain in a childlike state of dependence and identification with instinct. By heeding the serpent and eating the fruit, Adam and Eve are initiated into self-awareness, but at the price of a rupture in their original unconsciousness. They now have knowledge, but are cut off from unitive life.

Erich Neumann saw this archetypal pattern reflected in the psychological development of the individual. The infant begins in a state of oceanic merger with the mother, an unconscious wholeness in which its needs are automatically met. But in order to develop an independent ego, the child must gradually separate from the mother, establishing boundaries and learning to tolerate frustration. This “casts the mother out of paradise,” as she is no longer experienced as the source of total bliss but as an external object. The birth of the ego thus induces a sense of loss and guilt, a nostalgic longing for the original mother-child unity.

This struggle to separate from the maternal unconscious was projected onto cultural myths and rituals. Neumann saw rites of initiation and hero myths as symbolic enactments of the ego’s heroic struggle against the Great Mother. The hero must descend into the underworld, slay the dragons of the unconscious, and emerge as a self-determining individual. But there was always the danger of remaining stuck in the maternal realm, refusing the call to individuation. The hero had to resist the temptation to regress to childhood dependence.

This danger was symbolized in the Eden story by the expulsion from the Garden. Adam and Eve’s eating from the tree of knowledge initiated them into individual existence, but an existence now defined by separation and death. They acquired personal responsibility and self-awareness but lost access to immortal life and unitive consciousness. The self-determining ego was left with a residual sense of guilt and incompleteness, forever longing to return to the paradise it had overthrown.

The Ego-Self Axis and the Task of Individuation

For Neumann and Jung, the overarching goal of psychological development was the reintegration of the ego with the lost wholeness of the Self. The ego had to separate from the unconscious to attain consciousness, but this separation was only a necessary first step. The ultimate task was to relativize the ego and reconnect it to the archetypal realm. Jung called this lifelong process of psychic growth “individuation.”

The individuated Self was symbolized by the mandala, which now expressed a more integrated state of consciousness in which thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition were in harmony. The ego was no longer defensively repressing the unconscious but open to its living waters. The alienated hero was reconnected to the eternal Ground of life. This did not mean a regression to childhood merger but a mature synthesis of the one and the many, the conscious and unconscious poles of the psyche.

Edinger saw this process expressed in alchemical and mystical imagery. The alchemical “philosopher’s stone,” created through the union of opposites like masculine and feminine, spirit and matter, symbolized the realized Self. In mystical visions of saints and holy people, the individuated ego was beheld as a living mandala, a microcosm reflecting the divine macrocosm. Christ and Buddha were seen as models of the individuated Self, egos fully attuned to the infinite and eternal while remaining distinct.

On a mythological level, the goal of individuation was also reflected in eschatological visions of a “new heaven and earth,” a restored paradise in which the alienation of the ego was overcome. The original wholeness lost in the “fall” was recovered on a higher, more integrated level. Images of a sacred marriage between heaven and earth, God and soul, reflected the reuniting of the ego and unconscious. The telos of history was imagined as the self-realization of humanity and life’s return to its divine source.

In psychological terms, this meant that the ego had to voluntarily sacrifice its claim to autonomy and centeredness. It had to see through its own illusory separation and recognize itself as an expression of a deeper totality. This often involved a descent into the depths of the unconscious, what Jung called the “night sea journey.” The inflated, heroic ego had to die to its own self-will and be reborn in the service of the Self. Only then could it be an authentic vessel for the energies of the unconscious.

Language, Myth and Culture as Symbolic Extensions of Consciousness

The biblical story of the fall also points to the decisive role of language in the emergence of consciousness and culture. When Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge, the first thing they do is realize their nakedness and fashion clothing out of fig leaves. This “making conscious” of their difference and separateness is symbolically linked to the origins of language. To name something is to distinguish it, to mark it as separate. Self-awareness is thus inextricable from linguistic representation.

The Eden story is itself a linguistic phenomenon, a mythic narrative that gives symbolic form to the birth of consciousness. Myths in general can be seen as projections of the psyche’s encounter with the mystery of existence. They are symbolic templates that encode the archetypal patterns of human development in narrative form. Through myth and ritual, the tribal group participates in the sacred stories of the gods and heroes, giving a shared horizon of meaning to individual experience.

But myths are made possible by language, which allows the translation of lived reality into symbolic form. Language enables the human world to be woven into a web of shared meanings that transcend the individual psyche. It opens up an intermediate space between the unconscious and the external world, an imaginal realm in which the psyche can represent and reflect on itself. The birth of language is the birth of the distinctly human world, a world of culture and history distinct from the eternal present of nature.

The origins of language and culture may thus be intimately linked to the emergence of self-consciousness out of the unconscious. As the ego separated from the instinctual unity of nature, it required a symbolic system to mediate between inner and outer, self and world. Language allowed for the development of abstract thinking, imagination, and long-term memory – cognitive faculties that gave humans an evolutionary advantage. But it also created an experience of separation from direct, unmediated life. The word was an abstraction that stood between the ego and the world.

Culture can be seen as an extension and elaboration of the symbolic function of language. All the spheres of culture – art, religion, politics, economics, etc. – are made possible by the human capacity for symbolic representation. They are ways of ordering and making sense of reality that are unique to the human lifeworld. Like individual consciousness, they involve a separation from the instinctual and bodily realm of nature. They create a distinctly human universe of meaning and value.

But just as the individual ego risks becoming alienated from the unconscious, so too can culture become disconnected from its vital, non-rational sources. The biblical expulsion from Eden can be read as a mythic representation of this danger. Once humans have tasted from the tree of (self-)knowledge, they can never fully return to the original unity with nature. Culture will always be haunted by a sense of loss and nostalgia for a time before time, for the paradise of infancy. It must guard against the temptation to erect its symbolic constructs into absolutes, forgetting their roots in and dependence on the ever-moving waters of the unconscious.

Integrating Perspectives on the Edenic Myth of Consciousness

The Garden of Eden story, interpreted through a depth psychological lens, provides a rich symbolic template for understanding the origins, structure, and development of human consciousness. As we have seen, thinkers like Neumann and Edinger discerned in this myth an archetypal image of the birth of the ego out of the unconscious, the primal self-division that set the stage for the drama of human individuation. The Eden narrative, in this reading, is not a one-time event but a living symbol of the enduring existential condition of self-conscious humanity, forever caught between unity and multiplicity, innocence and knowledge, nature and culture.

Integrating this Jungian perspective with insights from contemporary evolutionary psychology and the broader comparative study of mythology allows us to appreciate the Eden story as a culturally specific inflection of the universal human encounter with the origins of selfhood. The “fall” into self-consciousness dramatized in Adam and Eve’s expulsion from paradise has deep parallels in the mythologies of diverse cultures, suggesting an archetypal process at work. At the same time, modern research on the evolution of language, symbolic reference, and theory of mind provides empirical grounding for the Jungian notion of a decisive leap in hominid cognition that birthed the cultural world.

The work of contemporary scholar David Tacey is particularly relevant here. In books like Gods and Diseases (2011), Tacey diagnoses the central malady of the modern psyche as its “loss of myth” – its disconnection from the sacred stories and images that traditionally mediated between consciousness and the unconscious. For Tacey, the Eden myth points to an enduring existential condition that requires constant symbolic renewal. The recovery of a sense of the sacred, he argues, is crucial to the healing of the modern mind.

Tacey’s emphasis on the transformative power of mythic symbols is deeply resonant with the Jungian reading of the Eden story. He stresses the importance of “mental symbiosis” – the capacity to enter into a living, imaginal relationship with the archetypal realities encoded in myth. This symbolic sensibility is precisely what the modern “fallen” condition of consciousness lacks. Reconnecting with myths like the Eden story is thus not a matter of literal belief but of creative, participatory engagement.

An interdisciplinary approach also highlights the intimate linkages between individual psychological development and the evolution of human culture as a whole. The Eden story, seen in a wider historical context, can be read as a mythic registration of the momentous transition from archaic, “participation mystique” consciousness to the more self-reflexive, dualistic consciousness of the ancient world. This shift set the stage for the emergence of the first large-scale civilizations with their advanced symbolic technologies of writing, mathematics, and urban organization. The biblical narrative of a “fall” from primal unity into alienation, on this view, reflects the ambivalent cultural memory of a world-historical transformation of human cognition and society.

These readings need not be seen as contradictory but rather as complementary, disclosing the archetypal resonance of the Eden story on both the ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels. The myth is a prism through which we can glimpse the basic structures of the human psyche as they unfold in both individual and collective development. Its symbols have a synchronic, archetypal aspect – embodying timeless patterns of psychological development – as well as a diachronic, cultural-historical aspect, reflecting actual turning-points in the evolution of human consciousness.

Ultimately, the Eden myth challenges us to reconnect the alienated ego to its unconscious ground while preserving its hard-won autonomy and self-awareness. As Jungians like Edward Edinger and Erich Neumann recognized, the task of individuation is not a simple regression to origin or instinct but a higher integration of the ego-Self axis, a “royal marriage” of the conscious and unconscious dimensions of the psyche. Only by consciously recuperating its roots in psychosomatic and ecological wholeness can the modern personality stave off the Faustian temptations of inflation and world-destruction.

This has urgent ethical and political implications in an era of accelerating technological change, ecological devastation, and the return of atavistic forms of ideology and belief. A post-Jungian sensibility, informed by contemporary models of human development, can help us re-envision the Eden story less as a bleak theodicy than as an initiatory myth for our time – a story that encodes both the perils and promise of the human experiment with reflective selfhood and culture. By consciously reappropriating its Edenic inheritance, the modern mind can rebalance itself and discover new, more integrated ways of being-in-the-world.

Such a perspective also has significant implications for psychotherapy and transformative practice in both Western and non-Western contexts. Seeing the ego’s condition through the lens of the paradise myth can reframe neurosis and psychopathology less as medical disorders than as spiritual crises reflecting the soul’s inherent telos of wholeness. Jungian techniques like active imagination, dream-work, and sand-play can be appreciated as ways of facilitating the dialogue between the conscious and unconscious layers of the psyche, thus regenerating the life-giving connection to the lost Self. At the same time, practices like yoga, meditation, and the cultivation of non-dual awareness can help dissolve the rigid boundaries of the ego and provide experiential, embodied access to more fluid, integrative states of being.

Paths forward lie, perhaps, in creative hybridizations of ancient myth and ritual with emergent techniques of neuropsychology, cybernetics, and the new sciences of complexity and self-organization. Just as the biblical Tree of Knowledge bore intermingled fruits of good and evil, the contemporary explosion of knowledge and technological power is inherently ambivalent, pregnant with both catastrophic and redemptive possibilities. We cannot undo our fateful eating of the fruit of self-consciousness; we can only follow its lead into an uncertain evolutionary future. The Eden story endures as a mythic reminder that the distinctive task and burden of the human is to advance the frontiers of consciousness itself – a dangerous yet holy charge. As Rabbi Tarfon says in the Pirkei Avot, “It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work, but neither are you at liberty to desist from it.”

The truths encoded in primordial myths like the Eden story are never simple or literal; rather, they provide multivalent, generative root metaphors through which the psyche can recognize and realize itself. In the face of postmodernity’s disenchantments and deconstructions, a reengagement with such myths is not atavistic but urgent, providing a symbolic compass for the ever-necessary work of psycho-spiritual integration at both the personal and collective levels. An integrative, developmentally-informed appreciation of the Eden myth can thus, perhaps, nurture a new micro- and macro-cultural ecology of consciousness, one that grounds the unfolding of our symbolic and technological capabilities in a remembrance of our corporeal, earthly, and cosmic rootedness. In such a space, knowledge might once more become wisdom, and history might realize itself as a pathway back to the timeless ground of being from which it springs.

The Symbolism of Eden_ Language, Consciousness and the Birth of the Ego

Bibliography

Campbell, J. (1968). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press.

Damasio, A. (2000). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Mariner Books.

Deacon, T. (1997). The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. W. W. Norton & Company.

Dennett, D. (1993). Consciousness Explained. Penguin Books.

Donald, M. (1991). Origins of the Modern Mind: Three Stages in the Evolution of Culture and Cognition. Harvard University Press.

Edinger, E. (1972). Ego and Archetype. Shambhala.

Edinger, E. (1984). The Creation of Consciousness: Jung’s Myth for Modern Man. Inner City Books.

Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Frazer, J. (1922). The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Macmillan.

Freud, S. (1913). Totem and Taboo. W. W. Norton & Company.

Geertz, C. (1966). Religion as a Cultural System. In Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion, ed. M. Banton. Tavistock Publications.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

Jacobi, J. (1959). Complex/Archetype/Symbol In the Psychology of C. G. Jung. Routledge.

Jung, C. G. (1953-1979). The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. 20 vols. Bollingen Series XX, Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1967). Symbols of Transformation. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 5. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1968a). Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 9. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1968b). The Philosophical Tree. Alchemical Studies. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 13. Princeton University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural Anthropology. Basic Books.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Neumann, E. (1956). The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Princeton University Press.

Otto, R. (1923). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford University Press.

Peterson, J. (1999). Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief. Routledge.

Ramachandran, V. S., & Blakeslee, S. (1998). Phantoms in the Brain. William Morrow.

Segal, R. (2004). Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Tacey, D. (2001). Jung and the New Age. Brunner/Routledge.

Tacey, D. (2011). Gods and Diseases: Making Sense of Our Physical and Mental Wellbeing. Harper Collins.

Tarnas, R. (2006). Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. Viking.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1992). The Psychological Foundations of Culture. In The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture, ed. J. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby. Oxford University Press.

Turner, V. (1967). The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Cornell University Press.

Von Franz, M.-L. (1995). Creation Myths. Shambhala.

Washburn, M. (1995). The Ego and the Dynamic Ground: A Transpersonal Theory of Human Development. State University of New York Press.

Watts, A. (1954). Myth and Ritual in Christianity. Thames & Hudson.

Wilber, K. (1979). No Boundary: Eastern and Western Approaches to Personal Growth. Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (1995). Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution. Shambhala.

Further Reading

Abram, D. (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. Pantheon Books.

Armstrong, K. (2005). A Short History of Myth. Canongate.

Barfield, O. (2011). Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry. Wesleyan University Press.

Baring, A. & Cashford, J. (1991). The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image. Penguin.

Bellah, R. (2011). Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age. Belknap Press.

Cassirer, E. (1953-1996). The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. 4 vols. Yale University Press.

Corbin, H. (1969). Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Ṣūfism of Ibn ʻArabī. Princeton University Press.

Gebser, J. (1985). The Ever-Present Origin. Ohio University Press.

Guenther, H. (1984). Matrix of Mystery: Scientific and Humanistic Aspects of rDzogs-Chen Thought. Shambhala.

Hillman, J. (1979). The Dream and the Underworld. Harper & Row.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. Dell.

Katz, S., ed. (1978). Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis. Oxford University Press.

Lachman, G. (2010). Jung the Mystic: The Esoteric Dimensions of Carl Jung’s Life and Teachings. Tarcher.

McGilchrist, I. (2009). The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press.

Neville, B. (2005). Educating Psyche: Emotion, Imagination and the Unconscious in Learning. Flat Chat Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1967). The Symbolism of Evil. Beacon Press.

Romanyshyn, R. (1982). Psychological Life: From Science to Metaphor. University of Texas Press.

Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge.

Shamdasani, S. (2003). Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge University Press.

Singer, T., & Kimbles, S., eds. (2004). The Cultural Complex: Contemporary Jungian Perspectives on Psyche and Society. Routledge.

Stein, M. (1996). Practicing Wholeness: Analytical Psychology and Jungian Thought. Continuum.

Sullivan, B. (1990). Psychotherapy Grounded in the Feminine Principle. Chiron Publications.

Thompson, W. I. (1998). Coming into Being: Artifacts and Texts in the Evolution of Consciousness. Palgrave Macmillan.

Turkle, S. (1992). Psychoanalytic Politics: Jacques Lacan and Freud’s French Revolution. Guilford Press.

Vaughan, F. (1995). Shadows of the Sacred: Seeing Through Spiritual Illusions. Quest Books.

Verene, D. P. (1981). Vico’s Science of Imagination. Cornell University Press.

Whitehead, A. N. (1929). Process and Reality. Macmillan.

Woodman, M., & Dickson, E. (1997). Dancing in the Flames: The Dark Goddess in the Transformation of Consciousness. Shambhala.

0 Comments