The Film That Saw Our Future

In 1976, screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky and director Sidney Lumet released a film so prescient about the coming media landscape that audiences didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Network wasn’t just satire—it was prophecy. Nearly fifty years later, we’re living in the world it predicted: a reality where algorithms dictate human worth, where outrage is currency, and where every radical movement becomes content to be monetized.

The film arrived at a pivotal moment in American culture. Watergate had shattered public trust in institutions. The Vietnam War had ended in defeat and disillusionment. The economy was stagnating. Television, which had promised to unite and inform the nation, was revealing itself as something more sinister—a force that could shape reality rather than merely reflect it. Into this moment of cultural anxiety, Chayefsky dropped a bomb disguised as entertainment.

What made Network so unsettling wasn’t its cynicism about television—plenty of critics had already pointed out TV’s corrupting influence. What made it prophetic was its understanding that television was merely the first iteration of something far more totalizing: a networked reality where human attention would become the ultimate commodity, where every aspect of existence would be measured, monetized, and controlled by forces beyond any individual’s comprehension or control.

The Power We Can’t Stop Serving

Paul Tillich defined God as the “ultimate concern”—that which we cannot help but serve, cannot escape communication with, and cannot exist without acknowledging. By this definition, Network identifies our new gods: the invisible networks of media, finance, and power that have grown beyond any government, religion, or ideology. These are powers we literally cannot stop serving because to disconnect from them is to cease to exist in any meaningful social or economic sense.

The film’s central insight is devastating in its simplicity: these networks don’t need to control us through force. They control us by making us complicit in our own subjugation, turning our very existence into content, our relationships into metrics, our deepest beliefs into ratings. We become willing participants in our own commodification because the alternative—disconnection—feels like death.

Consider how this plays out in our daily lives. We wake up and check our phones, not because anyone is forcing us to, but because we’ve become dependent on the dopamine hits of notifications, likes, and engagement. We craft our online personas not out of vanity but out of economic necessity—in a world where personal brand determines professional opportunities, authenticity becomes another performance metric. We participate in social media platforms we know are harmful because to opt out is to become invisible, irrelevant, disconnected from the flows of information and opportunity that constitute modern life.

This is what Tillich might have called idolatry—the elevation of finite concerns to ultimate status. But unlike traditional idolatry, which at least had the dignity of conscious choice, our servitude to these networks feels involuntary, systemic, inescapable. We serve them not through worship but through participation, not through belief but through behavior.

The Star Power That Made It Real

Network assembled a cast of actors at the peak of their powers: Faye Dunaway, William Holden, Peter Finch, and Robert Duvall. Each brought to their role a lifetime of craft and a deep understanding of the human condition that allowed them to ground Chayefsky’s heightened dialogue in recognizable emotion.

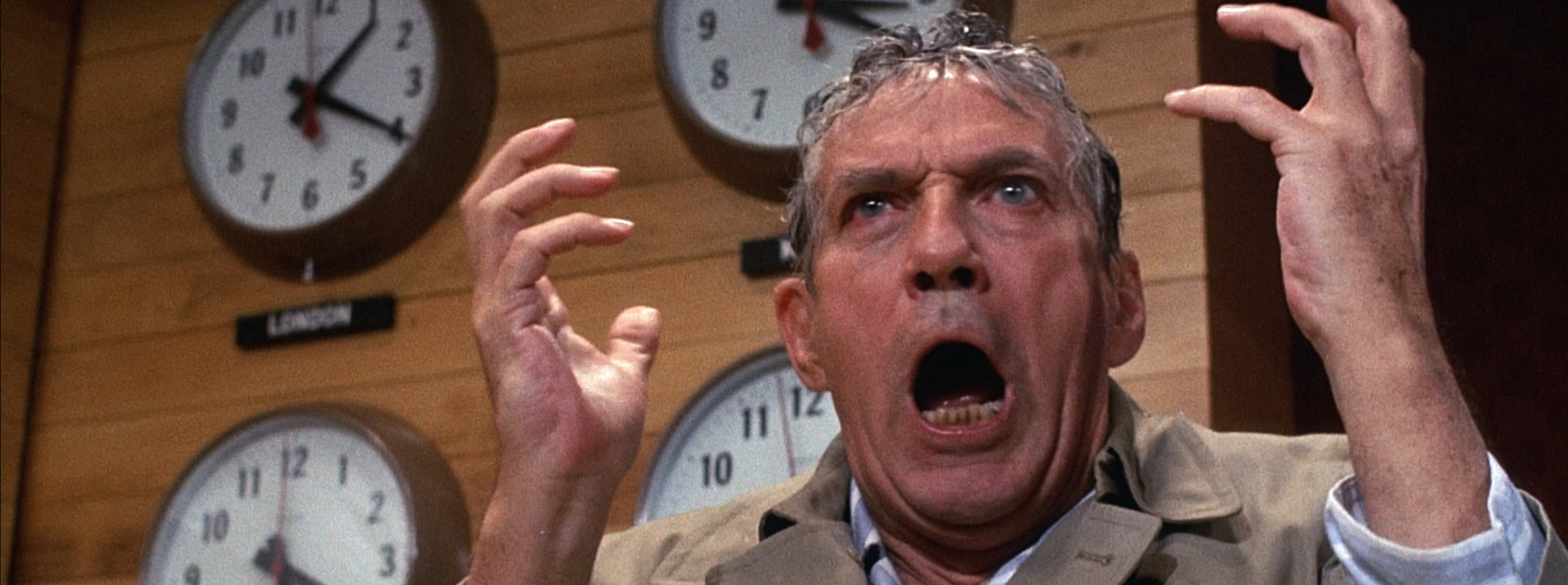

Peter Finch, who would die before the film’s release and win a posthumous Oscar, brought to Howard Beale a quality of genuine madness mixed with prophetic clarity. His performance walks a tightrope between comedy and tragedy, making us laugh at Beale’s excesses while recognizing the truth in his ravings. When Finch screams “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” he’s not just acting—he’s channeling something primal and real about human frustration with systems beyond our control.

William Holden, playing news division president Max Schumacher, represented the last generation of television professionals who believed in the medium’s potential for public service. Holden brought to the role a world-weary dignity, a sense of a man watching his life’s work perverted into something monstrous. His scenes with Dunaway crackle with the tension between old and new media, between human values and network imperatives.

Faye Dunaway’s Diana Christensen is perhaps the film’s most prescient creation—a character so merged with her medium that she’s ceased to exist as a fully human being. Dunaway plays her not as a villain but as a tragedy, a woman who’s traded her soul for success in a system that rewards sociopathy. Her performance is all sharp angles and manic energy, a human being running on the pure cocaine of ratings and market share.

Robert Duvall as Frank Hackett represents the corporate enforcer, the man who translates the abstract imperatives of capital into human misery. Duvall plays him with a terrifying banality—not a monster but a middle manager, doing what the system demands with neither pleasure nor regret.

The Rehearsal Process That Captured Lightning

But what made their performances transcendent was Sidney Lumet’s rehearsal process. For two weeks before filming, the cast sat around a table reading the script over and over, not as actors but as human beings discovering the truth of their characters. Lumet, who came from television and theater, understood that Chayefsky’s dialogue wasn’t naturalistic—it was operatic, prophetic, almost biblical in its cadences.

The rehearsal process served multiple functions. First, it allowed the actors to find the music in Chayefsky’s language. His characters don’t speak like real people; they speak like prophets, like forces of nature, like embodiments of systemic forces. The repetition allowed the actors to internalize these rhythms until they felt natural.

Second, the table work created a sense of ensemble. Despite the film’s critique of television, Lumet ran rehearsals like a theatrical production, emphasizing the relationships between characters rather than individual moments. This approach grounded the film’s larger-than-life pronouncements in recognizable human dynamics.

Third, the extended rehearsal period allowed the actors to excavate the pain beneath the rhetoric. Each character in Network is, in their own way, a victim of the system they serve. The rehearsals helped the actors find these vulnerabilities, making their characters human rather than mere mouthpieces for Chayefsky’s ideas.

Lumet would later say that he knew the film was working when, during one rehearsal, the actors spontaneously applauded after Ned Beatty delivered the “corporate cosmology” speech. They weren’t applauding Beatty’s performance—they were applauding the terrifying truth of what he was saying.

Network – “Mad as Hell” Speech

The Prescience of Paddy Chayefsky

How did Chayefsky see so far into our future? In 1976, there was no internet, no social media, no 24-hour news cycle. Cable television was in its infancy. The personal computer was a hobbyist’s toy. The idea of a globally networked information system where every human being would be simultaneously consumer and content creator would have seemed like science fiction.

Yet Chayefsky understood that television was just the beginning of something far more totalizing. He saw that once human attention became measurable and monetizable, every aspect of human life would be colonized by these metrics. He understood that the logic of ratings—the reduction of human complexity to numerical values—would eventually extend beyond television to encompass all human activity.

His insight came partly from his experience in television’s golden age. Chayefsky had written for live television in the 1950s, when the medium still had pretensions to art and public service. He’d watched as commercial imperatives slowly strangled creative freedom, as sponsors gained more control over content, as ratings became the only measure of success. He extrapolated from this experience a future where these tendencies would metastasize, consuming not just television but all media, all communication, all human interaction.

But Chayefsky’s prescience went deeper than mere trend extrapolation. He understood something fundamental about the nature of systems and power. He saw that once you create a system for measuring and monetizing human attention, that system develops its own logic, its own imperatives, its own momentum. It doesn’t matter what the humans running the system believe or intend—the system itself shapes their behavior, rewards certain actions and punishes others, until everyone involved becomes a servant of the metrics they created to serve them.

Marshall McLuhan’s Ghost in the Machine

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan argued that the medium is the message—that the characteristics of a communication medium shape the content it carries more than the content itself. Chayefsky took this insight and weaponized it, showing how television’s characteristics—its need for visual drama, its reduction of complex issues to simple narratives, its equation of truth with ratings—would eventually colonize all other forms of discourse.

In Network, we see this process in action. The news division, which once prided itself on objective reporting and public service, gradually succumbs to the logic of entertainment. But this isn’t presented as a moral failing of individuals—it’s shown as a systemic inevitability. Once news becomes subject to ratings, once it has to compete with entertainment for audience attention, it must become entertainment to survive.

McLuhan also spoke of the global village—the idea that electronic media would unite humanity in a single, interconnected community. Network shows the dark side of this vision: a global village where everyone is performing for everyone else, where privacy is impossible, where authentic human connection is replaced by mediated performance.

The film anticipates what McLuhan couldn’t quite see: that the global village would be ruled not by democratic participation but by algorithmic optimization, not by human values but by engagement metrics, not by conscious choice but by systemic imperatives that no one fully understands or controls.

The Speech That Defined An Era

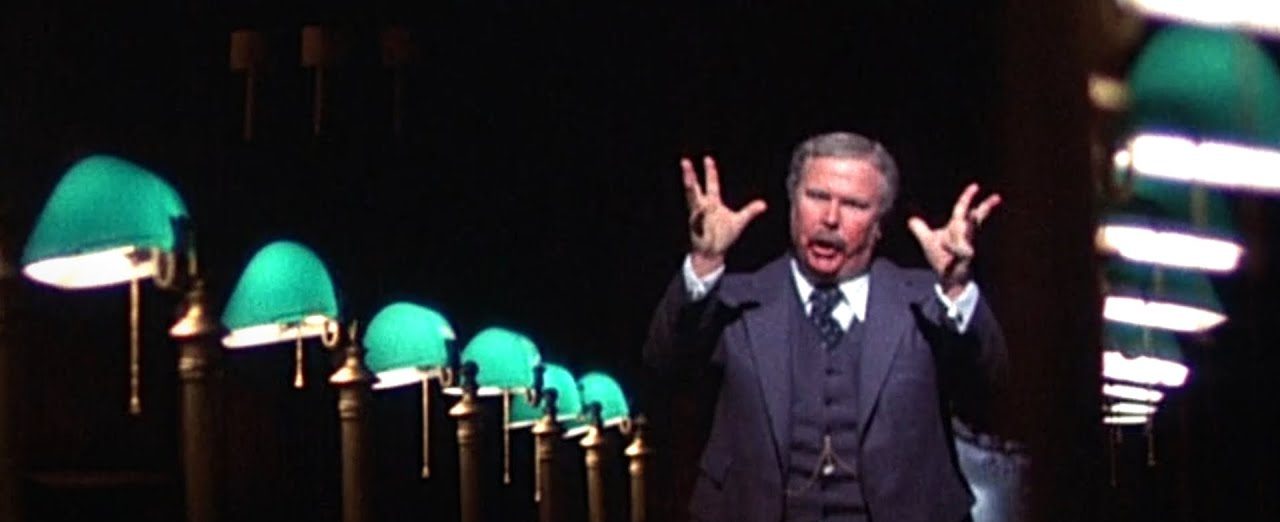

When Arthur Jensen (Ned Beatty) delivers his “corporate cosmology” speech to Howard Beale, he’s not just talking about business—he’s describing the new religion of our age. The scene is staged like a religious conversion, with Jensen as the prophet of a new world order and Beale as the reluctant convert:

“You have meddled with the primal forces of nature, Mr. Beale, and I won’t have it! Is that clear? You think you’ve merely stopped a business deal. That is not the case! The Arabs have taken billions of dollars out of this country, and now they must put it back! It is ebb and flow, tidal gravity! It is ecological balance!”

Jensen continues, his voice rising to prophetic intensity:

“There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM and ITT and AT&T and DuPont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today. What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state, Karl Marx? They get out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories, minimax solutions, and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments, just like we do.”

Network – Arthur Jensen’s “Corporate Cosmology” Speech

This scene transforms a corporate boardroom into a cathedral, complete with dramatic lighting and ecclesiastical staging. Jensen doesn’t present his vision as one option among many—he presents it as revealed truth, as the fundamental reality that underlies all apparent human activity. Nations, ideologies, religions—all are revealed as illusions, shadows cast by the only real forces in the world: the flows of capital and information.

What makes this speech so chilling is that Jensen isn’t wrong. His description of a world where national boundaries are meaningless, where ideological differences are subsumed by economic imperatives, where all human activity is reducible to “price-cost probabilities”—this is recognizably our world. The speech works because it tells a truth we don’t want to hear: that our human dramas, our political conflicts, our personal struggles all take place within a system whose logic transcends and shapes them all.

Money Beyond Money

In traditional societies, money was a tool—a medium of exchange that facilitated human relationships and values. We could “vote with our dollars,” subordinating economic activity to higher purposes. Money served human needs rather than determining them. It was possible to imagine and create spaces outside the money economy—gift economies, commons, places where different values could flourish.

But Network foresaw that in a hyper-networked world, this relationship would invert. Money would no longer serve human purposes; humans would serve monetary flows. The film presents this not as a conspiracy but as a systems effect—once you create global networks of instantaneous capital flow, once you make all human activities subject to financial measurement, the logic of money colonizes everything it touches.

The pound sterling speech in the film captures this perfectly. When the Saudi investors threaten to pull their money out of the network’s parent company, it’s presented not as a business decision but as a violation of natural law. The currency flows between nations are described in terms of “ebb and flow, tidal gravity, ecological balance”—as if the movement of capital were as fundamental and unchangeable as the movement of the planets.

This transformation of money from tool to master reflects a deeper transformation in how we understand value. In a traditional economy, value was ultimately grounded in human needs and desires—things had value because people needed or wanted them. But in the networked economy Network depicts, value becomes self-referential. Things have value because the market says they have value. Ratings determine what’s newsworthy. Stock prices determine corporate behavior. Metrics determine human worth.

Douglas Rushkoff and the Theft of Time

Douglas Rushkoff, writing decades after Network, would articulate how digital technology accelerates and intensifies the dynamics Chayefsky identified. In Rushkoff’s analysis, digital networks don’t just mediate human activity—they reshape it according to their own temporal logic. Everything must happen in “real time,” at the speed of electronic transmission, leaving no space for reflection, consideration, or human-scaled rhythms.

Network anticipates this acceleration. The film shows how the pressure for immediate ratings, instant gratification, and continuous engagement destroys the possibility of thoughtful journalism, meaningful relationships, or coherent political action. Characters are constantly interrupted, constantly responding to the latest crisis, constantly adjusting their behavior to the latest numbers. There’s no time to think, only to react.

This theft of time is perhaps the network’s greatest power. By keeping us constantly engaged, constantly responding, constantly optimizing our performance for the algorithm, it prevents us from stepping back and questioning the system itself. We’re too busy playing the game to ask whether the game is worth playing.

The Co-option of All Resistance

Perhaps the film’s most chilling insight is how it shows every form of resistance being absorbed into the system it opposes. The Marxist revolutionaries in the film—the Ecumenical Liberation Army—don’t abandon their ideology when they get their own TV show. They still spout the same revolutionary rhetoric, still claim to oppose the capitalist system. But now they’re worried about their ratings. They negotiate contracts. They hire agents. They become content providers in the very system they claim to overthrow.

This is our reality magnified a thousandfold. Every person with a YouTube channel, every activist with a Twitter account, every therapist trying to help people while maintaining an online presence—we’re all subject to the same algorithmic masters. We serve the engagement metrics whether we believe in them or not. We optimize our content for visibility, shape our message for virality, craft our personas for maximum impact.

The system doesn’t need to suppress dissent—it monetizes it. Black Lives Matter becomes a hashtag. Climate activism becomes influencer content. Anti-capitalist critique becomes a bestselling brand. Every authentic human emotion, every genuine political conviction, every attempt at resistance can be packaged, branded, and sold back to us as content.

This co-option operates through a perverse alchemy. The more successful your message, the more it must conform to the medium’s demands. Want to spread awareness about inequality? Better make it snappy and shareable. Want to organize political resistance? Better master the algorithm. Want to promote human connection? Better build your platform first.

The Ecumenical Liberation Army’s transformation from revolutionaries to content creators isn’t played for simple irony. It’s a tragedy—people with genuine convictions about changing the world reduced to performing their convictions for an audience. Their revolution becomes a show, their ideology becomes a brand, their struggle becomes entertainment.

Faye Dunaway’s Prophecy of Loneliness

Diana Christensen represents something even more disturbing than corporate evil—she represents corporate emptiness. Faye Dunaway plays her as a woman so thoroughly colonized by network logic that she’s ceased to exist as a fully human being. She doesn’t have relationships; she has strategic partnerships. She doesn’t have conversations; she has pitches. She doesn’t have emotions; she has ratings responses.

In her climactic scene with Max Schumacher, Diana delivers a speech that could have been written about our current epidemic of loneliness:

The most devastating moment comes when she acknowledges what she’s become:

“I’m indestructible, Max. I’m a machine. I’m educated, brilliant, and on my way to the top. I’ve got a contract for another year, and there’s a million-dollar insurance policy on my life. I’m the incarnation of the American dream.”

She knows she’s “indestructible and indifferent as the temples of the gods,” but also that this power comes at the cost of her humanity. When Max tells her she needs to feel something, to connect with another human being, she admits she can’t—she’s too deeply merged with the network itself. She’s achieved everything the system rewards—success, power, influence—but in the process has become incapable of the very human connections that make life meaningful.

Diana’s tragedy anticipates our current crisis of connection. We have more ways to communicate than ever before, yet loneliness has reached epidemic proportions. We’re constantly connected but rarely present. We have thousands of “friends” but few intimate relationships. We perform intimacy online while struggling with it offline.

The film suggests this isn’t a personal failing but a systemic effect. The same forces that make Diana successful—her ability to reduce everything to metrics, to see people as resources, to optimize every interaction for maximum return—make her incapable of genuine human connection. She can’t turn off the network logic that made her powerful. She sees Max not as a lover but as a “viable property.” She experiences her own emotions as content to be packaged and delivered.

The Religious Experience of News

The film’s transformation of news into religious spectacle reaches its apex with Howard Beale’s on-air sermons. The newsroom becomes a church, the anchor desk an altar, and the audience a congregation desperate for meaning in a meaningless world. Beale doesn’t report news; he channels cosmic truth. He doesn’t inform; he prophesies. He doesn’t analyze; he reveals.

The evolution is gradual and logical. It begins with Beale’s mental breakdown—his announcement that he’ll kill himself on air. This generates massive ratings, teaching the network a terrible lesson: authenticity sells, pain entertains, breakdown is breakthrough. From there, each escalation follows naturally. If threatening suicide gets ratings, what about ranting about the state of the world? If ranting works, what about prophesying? If prophesying works, what about creating a full religious experience?

By the film’s climax, Beale’s news show has transformed into something unrecognizable. He enters through stained glass doors. Fortune tellers and gossip columnists flank him like disciples. The audience chants responsively. The news has become not just entertainment but ritual, not just information but revelation.

But even this genuine human need for transcendence is commodified. Beale’s mental breakdown becomes must-see TV. His prophecies are measured in rating points. His assassination is planned not for political reasons but because his numbers are slipping. The network gives the people what they want—meaning, purpose, someone to tell them what’s really going on—but only as long as it’s profitable.

This commodification of the sacred anticipates our current moment perfectly. Every spiritual practice becomes a wellness brand. Every prophet becomes an influencer. Every revelation becomes content. We hunger for authentic spiritual experience, but we can only access it through mediated channels that transform it into its opposite.

Selling Our Own Rebellion Back to Us

The genius of our current system, which Network predicted with uncanny accuracy, is that it doesn’t need to suppress dissent—it monetizes it. Every critique of capitalism can become a bestselling book. Every call for revolution can become a viral video. Every authentic human emotion can be packaged, branded, and sold back to us as content.

This process operates through what we might call algorithmic capture. You start with genuine conviction—about inequality, about climate change, about human connection. You want to share these convictions, to make a difference. So you go online. You post. You tweet. You make videos.

At first, your authentic voice finds an authentic audience. But then the algorithm notices you. Your engagement metrics are good. You’re driving traffic. You’re creating value. Slowly, imperceptibly, you begin to optimize. You notice which posts get more engagement. You learn what triggers the algorithm. You adapt your message to what works.

Before you know it, you’re not expressing your convictions—you’re performing them. You’re not sharing your truth—you’re creating content. You’re not building a movement—you’re building a brand. The very passion that drove you to resist the system has been transformed into fuel for the system’s expansion.

Network shows this process in miniature through the Ecumenical Liberation Army, but we live it at scale. Every subculture, every resistance movement, every alternative lifestyle eventually becomes a market niche. Punk becomes fashion. Protest becomes performance. Revolution becomes aesthetic.

The system’s genius is that it doesn’t fight our rebellion—it funds it, promotes it, packages it, and sells it back to us. Our own disowned agency returns to us as product, as content, as brand. We consume our own resistance, purchase our own rebellion, subscribe to our own revolution.

Psychological Trauma, Deflection, and Grief

Through the lens of psychological trauma theory, we might understand our relationship with these networks as a form of collective trauma response. We know the systems are harming us—increasing anxiety, destroying attention spans, commodifying relationships, alienating us from ourselves and each other. Yet we feel powerless to disconnect, trapped in patterns of behavior that perpetuate our own suffering.

Trauma theory speaks of deflection—the ways we avoid confronting the source of our pain by redirecting our energy elsewhere. In Network, every character exhibits this deflection. Max knows the network is destroying journalism but focuses on his affair with Diana. Diana knows she’s incapable of love but throws herself deeper into work. Howard knows he’s being exploited but continues prophesying. Frank knows he’s serving inhuman masters but focuses on the next quarter’s profits.

We see the same deflection in our daily lives. We know social media is making us miserable, but we blame ourselves for lacking discipline rather than questioning the system. We know the algorithms are manipulating us, but we try to game them better rather than refusing to play. We know we’re addicted, but we download apps to manage our addiction rather than addressing its source.

The stages of grief offer another lens through which to view our predicament. Denial: “I’m not addicted to my phone; I can quit anytime.” Anger: “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” Bargaining: “If I just use these platforms more mindfully, more strategically, more authentically…” Depression: “There’s no escape. This is just how the world works now.”

But where is acceptance? Not acceptance as resignation, but acceptance as clear-seeing, as the first step toward genuine change? Network suggests that real acceptance might require something more radical than we’re prepared for: the willingness to disconnect, to accept smaller audiences, less power, fewer metrics. To choose human connection over network connection, even when it costs us visibility, relevance, success by any metric the system recognizes.

The Question Network Poses

The film ends not with answers but with a terrible question: Are we capable of disconnecting from these networks long enough to save ourselves? Or are we, like Diana Christensen, so fundamentally creatures of these systems that we’ll ride them all the way to our destruction?

This question has only become more urgent in the decades since Network‘s release. The technologies have changed—television gave way to the internet, broadcast gave way to social media, Nielsen ratings gave way to engagement algorithms—but the fundamental dynamics remain the same. Systems designed to measure and monetize human attention have colonized ever-larger portions of human experience. The logic of metrics has extended from television to every aspect of life.

We are all Howard Beale now, performing our authenticity for an invisible audience, turning our pain into content, our breakdowns into breakthroughs. We are all Diana Christensen, optimizing ourselves for success in systems that reward sociopathy, becoming machines in service of the machine. We are all the Ecumenical Liberation Army, turning our resistance into revenue streams, our revolution into ratings.

Are We Powerless, or Is There Another Way?

The film’s final image—Max walking away from Diana, choosing disconnection over complicity—offers a hint of possibility. It’s not a triumphant moment. Max doesn’t destroy the network or save Howard Beale or transform the system. He simply walks away, choosing human-scaled existence over network-mediated success.

This gesture feels both necessary and insufficient. Necessary because someone has to start somewhere, has to demonstrate that disconnection is possible. Insufficient because individual withdrawal doesn’t challenge systems that shape billions of lives. Max saves himself, perhaps, but the network continues its colonization of human experience.

Yet maybe this is where resistance begins—not with grand gestures or viral movements, but with small acts of refusal. Choosing conversation over content. Choosing presence over performance. Choosing connection over metrics. Choosing to value what can’t be measured, to preserve what can’t be monetized, to protect what can’t be optimized.

Network doesn’t tell us whether such resistance can succeed. It simply shows us the cost of not trying: a world where every human value is subordinated to the network, where every relationship is mediated by algorithms, where even our own deaths become content for others to consume.

The prescience of Paddy Chayefsky’s vision leaves us with an urgent task. We can no longer claim ignorance about where these systems lead. We can no longer pretend that technological progress automatically serves human flourishing. We can no longer assume that someone else will solve the problem of our collective captivity to forces we’ve created but no longer control.

As we scroll through our feeds, refresh our metrics, and optimize our content for engagement, we might remember Howard Beale’s first and most important message: “I’m a human being, goddammit! My life has value!” The question is whether we still believe this, whether we’re willing to act on it, whether we can find ways to assert human value against systems that recognize only exchange value, attention value, metric value.

The network is everywhere now, in our pockets, in our homes, in our most intimate moments. Its logic shapes our days and invades our dreams. We are all creatures of the network, servants of algorithms we don’t understand, players in games whose rules we didn’t write and can’t change.

But we’re also human beings, capable of choice, connection, and refusal. Network prophesied our present, but it doesn’t have to determine our future. The question remains open: Will we continue to serve powers we can’t stop serving, or will we find ways to reclaim agency, rebuild community, and restore human values to their rightful place above the metrics that currently rule our lives?

0 Comments