How Friston’s Mathematics and Gendlin’s Philosophy Validate Jung’s Architecture of Mind

A remarkable theoretical convergence is occurring in contemporary cognitive science, yet it remains largely unrecognized even by those working within these frameworks. Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle, with its rigorous mathematical formulation of hierarchical predictive processing, and Eugene Gendlin’s Process Model, with its precise philosophical articulation of felt meaning and carrying forward, are independently validating core insights from Carl Jung’s analytical psychology. This validation extends beyond surface similarities to reveal that Jung’s supposedly mystical descriptions of psyche actually captured fundamental organizational principles that govern all intelligent systems, principles now demonstrable through Bayesian mathematics and empirical neuroscience.

The tragedy is that this convergence remains invisible to most researchers. Friston’s work is discussed in computational neuroscience circles, Gendlin’s in phenomenological philosophy and psychotherapy, and Jung’s primarily in depth psychology and clinical contexts. Each tradition uses different vocabularies, publishes in different journals, and attracts different audiences. Yet when we examine their core propositions about the nature of intelligence, consciousness, and systemic organization, we find they are describing the same fundamental architecture through different lenses.

The Mathematical Necessity of Tripartite Structure

Friston’s Free Energy Principle demonstrates mathematically that any self-organizing system capable of maintaining itself against entropy must possess at least three hierarchically arranged components. This isn’t merely an empirical observation but a mathematical necessity derivable from first principles. The system must have a generative model that predicts sensory inputs, a mechanism for comparing predictions to actual inputs generating prediction error, and a higher-order process that updates the model based on these errors. Without all three components, the system cannot maintain the bounded surprisal necessary for continued existence.

This tripartite structure appears at every level of biological organization. At the cellular level, we see sensory receptors, comparison mechanisms, and adaptive responses. At the neural level, we find primary sensory areas, error-computing regions, and higher cortical areas that update predictive models. At the psychological level, we encounter immediate experience, reflective awareness, and integrative processing. The mathematics are scale-invariant, applying equally to bacteria navigating chemical gradients and humans navigating complex social situations.

What makes this particularly relevant to Jung is that Friston’s mathematics demonstrate why conscious systems specifically require this three-part architecture to function. The moment a system becomes capable of modeling itself, it necessarily develops hierarchical levels that can become desynchronized. The top level, which in humans corresponds to abstract conscious cognition, can develop models that deny or fail to perceive signals from lower levels. This isn’t a bug but an inevitable consequence of hierarchical predictive processing with sufficient complexity.

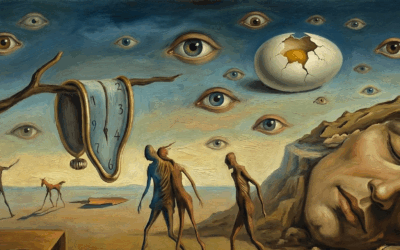

Jung intuited this structure through careful introspection and clinical observation. His model of ego, personal unconscious, and collective unconscious maps precisely onto Friston’s hierarchical levels. The ego corresponds to the highest level of abstract modeling, the personal unconscious to intermediate processing that remains below conscious threshold, and the collective unconscious to the deepest generative models shaped by evolutionary history. Jung’s “complexes” are what Friston would call strongly weighted priors that resist updating, creating persistent prediction errors that manifest as psychological symptoms.

Gendlin’s Philosophical Bridge

Eugene Gendlin provides the philosophical framework that bridges Friston’s mathematics with Jung’s phenomenology. His concept of “felt sense” describes precisely what occurs when different levels of the predictive hierarchy interact. The felt sense isn’t just emotion or bodily sensation but the subjective experience of prediction error when higher and lower levels of processing are attempting to synchronize. Gendlin’s “carrying forward” is the process by which this error signal drives model updating, allowing the system to evolve toward reduced free energy.

Gendlin’s Process Model articulates how meaning emerges from the interaction between what he calls “occurring” and “implying.” In Friston’s terms, occurring corresponds to current sensory evidence while implying represents the generative model’s predictions. The tension between them creates what Gendlin calls “felt meaning,” which guides the organism toward resolution. This is exactly what Jung described as the “transcendent function,” the psychological mechanism that bridges conscious and unconscious contents to produce new understanding.

The philosophical precision Gendlin brings is crucial because it explains why Jung’s therapeutic techniques actually work. Active imagination, in which patients engage with autonomous complexes through creative expression, allows different levels of the predictive hierarchy to communicate through a shared symbolic medium. Dream analysis provides access to lower-level processing that’s usually filtered out by conscious attention. The seemingly mystical process of individuation is actually the systematic reduction of prediction error between hierarchical levels, leading to an integrated, coherent generative model.

The Three-Part Structure in Jungian Terms

Jung’s clinical observations led him to recognize that psychological health requires communication between at least three distinct processing centers. The ego, as the center of consciousness, operates through abstract conceptual models that can become disconnected from embodied reality. The shadow represents everything the ego’s model excludes or denies, creating systematic prediction errors that manifest as projections and neurotic symptoms. The Self, Jung’s term for the totality of conscious and unconscious processes, emerges when all levels achieve synchronization.

This isn’t metaphorical but describes actual neurocognitive architecture. The precuneus, which recent neuroscience identifies as crucial for self-referential processing and consciousness, serves as the bridging mechanism Jung called the transcendent function. When this bridging fails, the ego inflates, believing itself to be the entire system while remaining ignorant of ongoing subcortical processing. This inflation isn’t just psychological but represents measurable desynchronization between cortical and subcortical networks.

Jung’s concept of possession by archetypal energies describes what happens when lower-level processing overwhelms higher-level control. In Friston’s framework, this occurs when prediction errors become so large that the system undergoes phase transition, with lower-level priors suddenly dominating conscious experience. The archetype isn’t a mystical entity but a deeply embedded generative model shaped by evolutionary pressures, what Friston calls “empirical priors” inherited across generations.

The individuation process Jung described involves progressively integrating these different levels, allowing the ego to perceive and incorporate previously unconscious material. Each confrontation with shadow or archetypal content represents an opportunity for model updating, reducing prediction error and achieving greater coherence. The “circumambulation of the Self” Jung described is the iterative process of error reduction that Friston’s mathematics prove necessary for any self-organizing system.

Clinical Implications of the Convergence

Understanding this convergence has profound implications for psychotherapy. When clinicians recognize that Jung’s techniques target specific levels of hierarchical predictive processing, they can apply them more precisely and effectively. Somatic approaches access lower-level body-based predictions that cognitive therapy cannot reach. Dreamwork reveals the generative models operating below conscious awareness. Symbol and metaphor provide a medium through which different levels can communicate despite operating in different representational formats.

Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing, which focuses on releasing trapped trauma from the body, works because it addresses prediction errors encoded at subcortical levels that conscious reflection cannot access. The “felt sense” that Levine helps clients develop is literally the perception of these prediction errors, allowing higher-level processing to update based on lower-level signals. The shaking and discharge Levine observes aren’t mysterious releases of “energy” but the observable result of system-wide model updating.

Similarly, EMDR’s bilateral stimulation may work by temporarily disrupting the usual hierarchical processing, allowing traumatic memories encoded at different levels to reconnect and update. The eye movements don’t magically heal trauma but create conditions for prediction error to flow between usually isolated levels of processing. This explains why EMDR can achieve rapid results where purely cognitive approaches fail: it addresses the mathematical necessity of multi-level integration.

Why This Matters Now

The rehabilitation of Jung through Friston and Gendlin matters because it recovers a sophisticated understanding of consciousness that modern psychology largely abandoned. In rushing to appear scientific, psychology rejected Jung’s insights as unverifiable mysticism. But Jung was describing real phenomena that he simply lacked the mathematical and neuroscientific framework to explain in contemporary terms. His careful phenomenological observations captured truths about consciousness architecture that we’re only now able to validate empirically.

This convergence suggests that the split between depth psychology and cognitive neuroscience is artificial and counterproductive. Jung’s analytical psychology, Friston’s computational neuroscience, and Gendlin’s process philosophy are describing the same reality from different vantage points. Recognizing this allows us to integrate their insights, creating a more complete understanding of consciousness and psychopathology.

Furthermore, this synthesis explains why certain therapeutic approaches work while others fail. Techniques that address only one level of the hierarchy, whether purely cognitive or purely somatic, will have limited effectiveness because they ignore the mathematical necessity of multi-level integration. Effective therapy must facilitate communication between all three levels, allowing the system to achieve the synchronization that Jung called individuation and Friston calls free energy minimization.

The Unconscious as Subcortical Intelligence

Perhaps the most radical validation of Jung is the recognition that what he called “the unconscious” isn’t a mysterious realm but observable subcortical processing operating with genuine intelligence below conscious awareness. These systems aren’t primitive or merely reactive but engage in sophisticated predictive processing, pattern recognition, and adaptive behavior. They possess their own models of reality, their own goals and strategies, their own forms of memory and learning.

When Jung spoke of autonomous complexes with their own intentionality, he was describing what neuroscience now recognizes as semi-independent processing modules with their own predictive models. These aren’t metaphors but measurable neural networks that can operate independently of conscious control. The amygdala maintains its own predictions about threat, the basal ganglia their own models of reward and habit, the insula its own representations of bodily state. Each operates according to Friston’s mathematics, minimizing prediction error within its domain.

The collective unconscious, Jung’s most controversial concept, corresponds to what Friston calls empirical priors inherited through evolution. These aren’t mystical memories but deeply embedded generative models that shape perception and behavior across all humans. The “archetypes” are statistical regularities in the environment that evolution has encoded into our neural architecture: the dangerous predator, the nurturing mother, the wise elder, the trickster who disrupts social order. These patterns appear across cultures not through some mystical collective memory but because they reflect universal features of the environments in which human consciousness evolved.

The Temporal Architecture: How Post-Jungians Anticipated Modern Neuroscience

The document’s articulation of consciousness as three parts operating at radically different timescales provides stunning validation for post-Jungian theorists who extended Jung’s original insights. Edward Edinger, Erich Neumann, and James Hillman each intuited aspects of this temporal architecture through clinical observation and phenomenological analysis, developing concepts that now appear remarkably prescient in light of contemporary neuroscience.

The fundamental insight that “all adaptive systems require a three-part architecture to correct errors and learn from experience” maps precisely onto Jung’s tripartite model of psyche. But the post-Jungians went further, recognizing that these weren’t just structural divisions but temporal ones. Edinger’s concept of the ego-Self axis wasn’t merely about connection between conscious and unconscious but about bridging radically different temporal domains. The ego operates in extended time, planning futures and analyzing pasts, while the Self encompasses the immediate subcortical present that exists outside temporal elaboration.

When Edinger warned about the dangers of ego-Self alienation, he was describing what we now understand as temporal desynchronization. The ego, operating in its extended temporal modeling, loses the ability to perceive signals from systems operating in immediate time. This isn’t metaphorical disconnection but literal temporal isolation. The abstract cognitive system, projecting decades into past and future, cannot perceive the subcortical system’s millisecond-by-millisecond responses to present reality. Edinger’s “inflation” occurs when the ego believes its temporal projections are more real than immediate embodied experience.

Neumann’s Developmental Stages as Temporal Integration

Erich Neumann’s stages of consciousness development gain new significance when understood as progressive achievements in temporal integration. The uroboric stage represents consciousness before temporal extension, when all systems operate in the immediate present like the dolphin consciousness described in the document. The emergence of the ego represents the development of extended temporal modeling, the capacity to project beyond the immediate that makes human consciousness both powerful and problematic.

Neumann’s “centroversion,” the spiral development toward greater wholeness, can now be understood as the progressive capacity for systems operating at different timescales to perceive and integrate with each other. Each developmental crisis Neumann described represents a moment when temporal desynchronization becomes untenable, forcing the psyche to develop new bridging capacities. The hero’s journey isn’t just metaphorical but describes the literal descent from extended temporal modeling back to immediate experience, the confrontation with subcortical realities frozen in different temporal moments, and the achievement of new synchronization.

What Neumann called the “distress of the ego” in confronting the unconscious is precisely the disorientation that occurs when systems operating at different timescales attempt to communicate. The ego, accustomed to its elaborate temporal projections, experiences profound anxiety when forced to encounter the immediate, non-temporal intelligence of subcortical systems. This isn’t regression but necessary return to base-level synchronization, what the document identifies as essential for resolving trauma’s temporal freezing.

Hillman’s Autonomous Emotions as Temporal Intelligences

James Hillman’s radical reimagining of emotions as autonomous intelligences with their own perspectives gains extraordinary validation from this temporal framework. Hillman insisted that emotions weren’t just feelings but ways of seeing, each with its own intelligence and intentionality. He argued against the ego’s colonization of emotional life, its tendency to interpret all feeling through its own temporal lens.

The document’s description of “three parts operating at radically different timescales” that “cannot fully understand each other’s languages” provides the neurobiological basis for Hillman’s phenomenological observations. When Hillman wrote about anger having its own intelligence, fear its own wisdom, joy its own perspective, he was recognizing that these intermediate emotional systems operate in different temporal frames than abstract cognition. They’re not primitive or less intelligent but speak a different temporal language.

Hillman’s critique of literalism in psychology takes on new meaning. Literalism occurs when the abstract system, operating in extended time, tries to force immediate experience into its temporal categories. When therapy becomes obsessed with narrative, with making sense of the past and planning the future, it operates only at the cognitive temporal level. Hillman’s insistence on staying with the image, on not rushing to interpret or explain, represents respect for the different temporal domains in which psychological life unfolds.

His concept of “pathologizing” as necessary to soul-making reflects understanding that symptoms emerge from temporal desynchronization. Depression isn’t just negative thinking but temporal collapse where future disappears. Anxiety isn’t just worry but temporal extension gone haywire, projecting threats across decades. Hillman’s approach of entering the symptom imaginally rather than analyzing it cognitively works because it meets the emotional system in its own temporal domain rather than trying to drag it into extended temporal modeling.

The Clinical Revolution Hidden in Plain Sight

The convergence of Friston’s mathematics with post-Jungian insights reveals that effective depth psychology has always worked by facilitating temporal synchronization. When Edinger had patients draw mandalas, he was providing a medium through which systems operating at different timescales could communicate through shared immediate creation. When Neumann traced mythological patterns, he was showing how human consciousness repeatedly navigates the challenge of temporal integration. When Hillman insisted on the autonomy of images, he was respecting the different temporal domains in which psyche operates.

The Spectral Labyrinth Technique mentioned in the document exemplifies what post-Jungians intuited: healing requires meeting all systems in shared immediate experience. Color, eye position, and felt sense are “too simple and too present to elaborate into complex temporal predictions,” forcing synchronization at base level. This isn’t new but represents rediscovery of what depth psychology knew phenomenologically. Jung’s active imagination, Edinger’s symbolic approach, Neumann’s creative expression, Hillman’s imaginal work—all create conditions for temporal synchronization without explicitly understanding the temporal mechanism.

Integration as Temporal Reconciliation

The post-Jungian concept of individuation as progressive integration gains precise meaning through temporal analysis. Integration isn’t about making the unconscious conscious in an informational sense but about enabling systems operating at different timescales to perceive each other. The individuated person isn’t someone who has analyzed all their complexes but someone whose subcortical immediacy, emotional intermediacy, and cognitive extension can communicate despite their temporal differences.

This explains why insight alone rarely produces lasting change. The cognitive system can develop elaborate understanding of patterns and traumas, building complex temporal narratives that explain everything yet change nothing. The subcortical system, frozen in traumatic moments, doesn’t need explanation but presence. It needs the cognitive system to stop projecting long enough to perceive what’s happening now, to register that the danger is past, that the present is different from the frozen moment.

Post-Jungians understood this implicitly, which is why they emphasized symbol, image, and creative expression over interpretation. These mediums operate across temporal domains, allowing systems that cannot understand each other’s languages to nonetheless perceive each other’s reality. A dream image can simultaneously hold immediate subcortical experience, intermediate emotional processing, and extended cognitive meaning. An artwork can bridge millisecond sensation with decade-spanning narrative.

The Mathematical Validation of Depth

What makes this convergence particularly significant is that it provides mathematical and empirical validation for approaches dismissed as unscientific. When Hillman argued for the reality of imaginal experience, he was recognizing that intermediate emotional systems have their own valid intelligence operating in their own temporal domain. When Edinger mapped the ego-Self axis, he was describing the challenge of bridging systems separated by vast temporal distances. When Neumann traced consciousness development through mythology, he was tracking humanity’s collective struggle with temporal integration.

Friston’s mathematics prove these aren’t metaphors but descriptions of necessary architectural features of conscious systems. The three-part structure isn’t optional but required for error correction and learning. The temporal differentiation isn’t pathological but inevitable once consciousness achieves temporal extension. The communication difficulties between parts aren’t failures but predictable consequences of systems operating at timescales differing by factors of millions.

This validation matters clinically because it suggests post-Jungian approaches aren’t just alternative perspectives but may be accessing aspects of consciousness architecture that cognitive approaches miss. The emphasis on image, symbol, and immediate experience isn’t primitive or regressive but sophisticated recognition that healing requires temporal synchronization cognitive analysis alone cannot achieve. The respect for autonomous complexes and emotional intelligences isn’t anthropomorphism but accurate perception that different systems operate with different temporal logics.

The post-Jungians, through careful phenomenological observation, discovered what neuroscience is only now proving: consciousness isn’t unitary but multiple, not just structurally but temporally differentiated, and health requires not just insight but synchronization across vast temporal distances. Their clinical techniques, developed through decades of practice, target precisely the temporal integration challenges that trauma disrupts and that modern life increasingly exacerbates. The rehabilitation isn’t just of Jung but of an entire lineage that preserved crucial wisdom about consciousness architecture through decades of scientific skepticism.

Toward an Integrated Science of Consciousness

The convergence of Friston’s Free Energy Principle, Gendlin’s Process Model, and Jung’s analytical psychology points toward an integrated science of consciousness that honors both rigorous empirical investigation and careful phenomenological observation. Jung’s work, far from being outdated mysticism, captured fundamental truths about consciousness architecture that mathematical and empirical approaches are now validating. His therapeutic techniques, developed through careful clinical observation, target the same mechanisms that Friston’s mathematics prove necessary for intelligent systems.

The tragedy is that this convergence remains largely unrecognized. Researchers in each tradition continue working in isolation, unaware that they’re describing the same phenomena through different languages. Clinicians trained in cognitive-behavioral approaches remain skeptical of depth techniques, not realizing they address different levels of the same hierarchical system. Depth psychologists defend their work against charges of being unscientific, not knowing that cutting-edge neuroscience validates their core insights.

Breaking down these artificial barriers would accelerate both theoretical understanding and clinical practice. Jung gave us the phenomenology, Gendlin the philosophy, and Friston the mathematics. Together, they provide a complete picture of how consciousness operates as a hierarchical predictive system that must integrate multiple levels of processing to function effectively. This integration isn’t mystical but mathematically necessary, not metaphorical but measurably real, not optional but essential for psychological health.

The rehabilitation is complete, even if unnoticed. Jung’s vision of the psyche as a complex system of interacting conscious and unconscious processes, requiring integration for health, stands validated by contemporary science. The question now is whether the various fields studying consciousness will recognize their common ground and work toward the integrated understanding that Jung, in his own way, achieved decades ago through careful observation of the human psyche.

0 Comments