Executive Summary: The Psychology of The Bacchae

The Core Conflict: Euripides’ masterpiece is the ultimate study of Repression. It pits Pentheus (The Rigid Ego) against Dionysus (The Irrational Id). It demonstrates that whatever we repress eventually returns to destroy us.

Jungian Key Concepts:

- Enantiodromia: The tendency of things to turn into their opposites. Pentheus, the hater of the irrational, becomes the most irrational of all (madness).

- Sparagmos: The physical dismemberment of the King represents the Psychological Dissociation that occurs when the Ego is overwhelmed by the Unconscious.

- The Devouring Mother: Agave represents the negative aspect of the Mother archetype—nature that creates life only to destroy it in a frenzy.

Clinical Relevance: A case study in Rigid Personality Structures and addiction. It shows that mental health requires a “sacrifice” to the irrational to prevent a total psychotic break.

What Happens in The Bacchae? A Jungian Analysis of Madness and the Repressed God

Euripides’ The Bacchae (405 BC) is not just a play; it is a warning shot fired across the bow of Western Civilization. Written at the end of the playwright’s life, it explores the terrifying consequences of denying the Irrational.

From the perspective of Carl Jung and Friedrich Nietzsche, this play is the foundational text on the relationship between the Apollonian (Order/Structure) and the Dionysian (Chaos/Ecstasy). It argues that the psyche cannot survive on logic alone. If the Ego (Pentheus) refuses to bow to the Unconscious (Dionysus), the Unconscious will tear the Ego apart.

Part I: The Return of the Repressed (Plot Summary)

The narrative is a psychological horror story about the failure of control.

- The Arrival: Dionysus, the god of wine, theater, and madness, returns to his birthplace, Thebes. He is angry because his family denies his divinity. He comes to prove that the irrational is real.

- The Resistance: King Pentheus, a young and rigid ruler, bans the worship of Dionysus. He sees the “Bacchic rites” (women dancing in the mountains) as a threat to law and order. He arrests the stranger (Dionysus in disguise).

- The Seduction: Dionysus does not fight Pentheus; he seduces him. He plays on Pentheus’s repressed voyeurism, convincing the King to dress as a woman to spy on the Maenads. This is the Return of the Repressed—the hyper-masculine King is forced to inhabit the feminine.

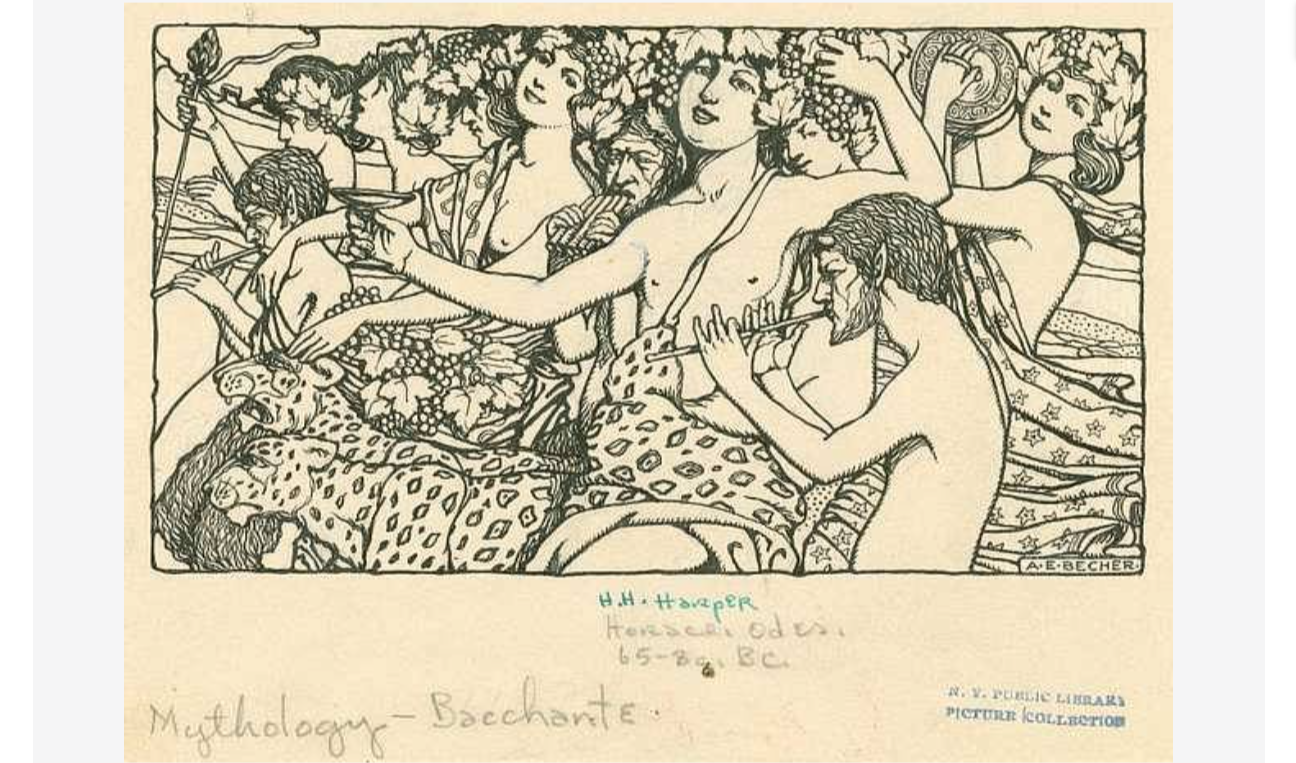

- The Sparagmos (Dismemberment): Pentheus goes to the mountain. The women, led by his own mother Agave, are in a divine trance. They mistake him for a mountain lion. In a frenzy of strength, they rip him limb from limb with their bare hands.

- The Recognition: Agave returns to Thebes carrying the “lion’s head” on a stick. As the trance fades, she realizes she is holding the head of her own son. The play ends with the total destruction of the Royal House.

Part II: Archetypal Figures

Dionysus: The Shadow of Civilization

Dionysus is the Archetype of the Unconscious. He is “The Loosener.” He dissolves boundaries—between man and beast, man and woman, sane and insane.

In Jungian therapy, Dionysus represents the Libido in its rawest form. He is the life force that flows. When it is honored, it brings joy and creativity (wine). When it is dammed up by repression, it becomes a flood that drowns the personality (madness).

Clinical Insight: Addiction is often a “misguided worship” of Dionysus. The addict seeks the transcendence (the loosening of the ego) that the god offers, but finds only destruction.

Pentheus: The Rigid Ego

Pentheus means “Man of Sorrow.” He represents the Hyper-Rational Ego. He is obsessed with control, boundaries, and “masculine” order.

He refuses to acknowledge that he has irrational desires. He projects his own lust onto the women (“They are just going to the woods to have sex!”). This Projection blinds him. Because he cannot see his own shadow, he is possessed by it. His journey into the woods in drag is the physical manifestation of his psychological inversion.

[Image of Jungian Apollonian vs Dionysian Diagram]

Agave: The Devouring Mother

Agave is the Negative Mother. Usually, the mother gives life; here, she takes it back.

In the ecstatic state, she sees her son as a beast. This symbolizes how the Collective Unconscious views the rigid Ego: as an obstacle to be removed. When the psyche is possessed by an archetype (the Maenad), personal relationships (mother-son) are obliterated by the archetypal drive.

Part III: Deep Psychological Themes

1. Enantiodromia: Running into the Opposite

Jung defined Enantiodromia as the principle that “superabundance of any force inevitably produces its opposite.”

Pentheus is the perfect example. He tries so hard to be sane and manly that he ends up insane and dressed as a woman.

The play teaches that we cannot simply “cut off” the parts of ourselves we don’t like. If we repress our sexuality, our aggression, or our need for ecstasy, they do not die. They go into the basement (the unconscious) and lift weights. When they come back up, they are monsters.

2. Sparagmos: The Fragmentation of the Self

The climax of the play is the Sparagmos—the tearing apart of the victim.

Psychologically, this is Dissociation or Psychosis. When the Ego is too brittle to bend, it shatters. The “dismemberment” of Pentheus is a metaphor for a nervous breakdown. The personality fragments because it cannot contain the energy of the Self.

Mythic Connection: This links to the story of Osiris (Egypt) and Orpheus (Greece). Dismemberment is often a precursor to rebirth, but for Pentheus, there is no rebirth because he resisted to the bitter end.

3. The Voyeur: Repression Fuels Desire

Why does Pentheus agree to dress as a woman and spy? Because his repression has created a fetish.

He is fascinated by what he bans. This is a crucial insight for modern psychology: The Censor is always a Pornographer. The part of the mind that forbids an impulse is secretly obsessed with it. Dionysus defeats Pentheus not by fighting him, but by exposing his secret desire to see the “orgies” he claims to hate.

Part IV: Clinical Relevance

The Necessity of the “Container”

The play argues for the necessity of Ritual. The Greeks had festivals for Dionysus so that the irrational could be experienced safely within a container.

In modern life, we lack these containers. We try to be “Pentheus” (productive, rational) 24/7. As a result, the Dionysian energy erupts in toxic ways: mass shootings, opioid epidemics, and political hysteria. Therapy serves as a modern Temenos (sacred space) where the irrational can be visited without destroying the patient.

Integrating the Shadow

Pentheus’s fatal flaw is his lack of Self-Knowledge. He thinks he is only his Persona (The King). He does not know he is also the Voyeur and the Beast.

Healing requires acknowledging the “Inner Bacchante.” We must admit that we have irrational, wild, and destructive impulses. By acknowledging them, we take away their power to possess us.

Part V: Conclusion

The Bacchae is a dark miracle. It shows that God is not just “Light” and “Order.” God is also the hurricane, the wine, and the tiger. To deny this is to invite destruction.

For the modern individual, the lesson is clear: Invite Dionysus to the table, or he will burn down the house. We must make space in our lives for the irrational, the emotional, and the ecstatic, or we risk the fate of Pentheus—dismembered by the very forces we tried to control.

Explore the Archetypes of Greek Drama

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

The Conflict of Apollonian & Dionysian

Hippolytus: The Rejection of Passion

Prometheus Bound: The Rebel Ego

Nietzsche and the Birth of Tragedy

The Devouring Mother & The Shadow

The Oresteia: The Cycle of Blood

Elektra: The Unconscious Fixation

The Women of Trachis: The Poison of Love

The Tragic Hero & The Ego

Seven Against Thebes: The Divided Self

The Philocetes: The Wound as Power

Alcestis: Sacrifice and Rebirth

Iphigenia in Tauris: The Exile

Iphigenia in Aulis: The Sacrifice

0 Comments