Executive Summary: The Psychology of Euripides’ Helen

The Core Premise: Euripides presents a radical “anti-tragedy” where Helen of Troy never went to Troy. Instead, the gods created a “Phantom” (Eidolon) out of clouds to take her place, while the real Helen waited in Egypt.

Jungian Analysis:

- The Eidolon: Represents the Projection (Anima/Shadow). The Greeks fought a ten-year war not for a woman, but for an internal image.

- Menelaus’s Crisis: Represents the ego’s refusal to let go of suffering. He struggles to accept that his “heroic war” was meaningless (The Sunk Cost Fallacy).

- The Two Helens: Symbolize the split between the Persona (social reputation) and the Self (authentic reality).

Clinical Relevance: This play is the ultimate case study for modern relationships, illustrating how we often fall in love with a fantasy (Phantom) and must grieve that fantasy to love the real person.

The War for Nothing: A Comprehensive Jungian Analysis of Euripides’ Helen

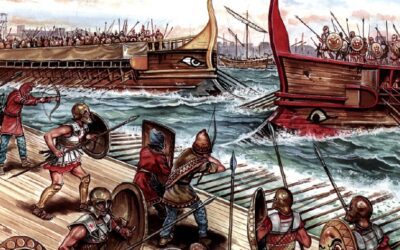

Of all the plays in the Greek canon, Euripides’ Helen (412 BC) is perhaps the most bizarre and the most psychologically incisive. It is a tragedy that feels like a comedy; a romance that feels like a philosophical treatise on the nature of reality. Written in the aftermath of the disastrous Sicilian Expedition—when Athens was bleeding to death from a pointless war—Euripides dared to ask a terrifying question: What if the war was fought for a ghost?

In this version of the myth, Helen never stepped foot in Troy. She remained chaste and faithful in Egypt. The woman Paris kidnapped, the woman the Greeks died for, the woman blamed for the destruction of civilization, was a Phantom (Eidolon) crafted by Hera out of “sky and breath.”

From the perspective of Depth Psychology, this play is not just a revisionist myth; it is a masterclass on the mechanism of Projection. It explores the terrifying gap between the Image (Imago) we hold in our minds and the Reality of the person standing before us. It challenges us to ask: Are we interacting with the world, or merely with our own phantoms?

Part I: The Origins of the Illusion

The Palinode of Stesichorus

Euripides did not invent this story. He borrowed it from the poet Stesichorus (c. 6th century BC). Legend has it that Stesichorus wrote a poem slandering Helen as an adulteress and was immediately struck blind by the gods. He realized his error—he had mistaken the “Phantom” for the reality. He then wrote the Palinode (Recantation), declaring that Helen never boarded the ships. His sight was instantly restored.

Psychological Insight: This backstory itself is a metaphor for psychological blindness. When we view others through the lens of the Shadow (demonizing them) or the Anima (idealizing them), we are “blind.” We do not see the human; we see the archetype. Clarity (sight) only returns when we withdraw the projection and acknowledge the reality.

The Historical Context: Athens in Crisis

Euripides wrote this play when Athens was collapsing. The Peloponnesian War had dragged on for decades. The parallels were obvious: The Athenians, like the Greeks of the Trojan War, were destroying themselves for “Honor” and “Empire”—concepts that, by 412 BC, felt increasingly like phantoms. The play suggests that Collective Psychosis occurs when a society pursues an abstract ideal (The Phantom) at the cost of human reality.

Part II: The Anatomy of the Archetypes

To understand the play’s depth, we must analyze the characters not as people, but as psychological structures.

| Character/Object | Jungian Archetype | Psychological Function |

| The Real Helen | The Self / The Soul | The authentic core of the personality that remains untouched by social reputation. She is “hidden in Egypt” (the Unconscious) while the Ego fights wars in the world. |

| The Eidolon (Phantom) | The Projection / The Persona | The “Hook” upon which society hangs its desires and hatreds. It is composed of “air”—it has no substance, yet it drives history. |

| Menelaus | The Rigid Ego | The conscious mind that identifies with its suffering. He defines himself as “The Conqueror of Troy.” To accept the truth forces him to confront the meaninglessness of his struggle. |

| Theoclymenus | The Shadow King | The Egyptian King who wants to marry Helen by force. He represents the “Possessive” aspect of the psyche that wants to own beauty rather than relate to it. |

Part III: The Mechanism of Projection (The Eidolon)

The central image of the play is the Eidolon. In Jungian therapy, we talk about the Imago—the internal image of a parent or lover that we carry in our minds. Projection happens when we overlay this Imago onto a real person.

The “Helen” of the World

To the Greeks, “Helen” was a symbol of ultimate beauty and ultimate destruction. But this symbol had nothing to do with the woman herself.

* Paris projected his Anima (Soul-Image) onto her. He didn’t want a relationship; he wanted the “World’s Most Beautiful Woman.”

* The Greeks projected their Shadow onto her. She became the scapegoat for their own violence.

Euripides physically separates these projections into a separate entity (The Phantom), allowing us to see the mechanism clearly. The Phantom is a narcissist’s mirror—it reflects whatever the observer wants to see.

The Tragedy of the Real Woman

Meanwhile, the real Helen is suffering in Egypt. This is the plight of the Authentic Self when the Persona takes over. When a person becomes a celebrity, a guru, or a “villain,” their humanity is exiled. They become a prisoner of their own image. Helen’s struggle in the play is not to be “saved” from Troy, but to be Seen as she actually is.

Part IV: The Crisis of Menelaus (The Ego)

The most psychologically fascinating character is Menelaus. He arrives in Egypt shipwrecked, dressed in rags, but clutching his “prize”—the Phantom Helen—whom he has hidden in a cave.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy of the Ego

When Menelaus meets the real Helen, he rejects her. He says:

> “I hold the troubles at Troy as my witnesses… I have my wife in a cave.”

Why does he reject the truth? Because the truth is devastating.

If this woman is the real Helen, then:

1. The woman in the cave is fake.

2. The ten-year war was for nothing.

3. The death of his friends (Achilles, Ajax) was meaningless.

4. His identity as “The Victor” is hollow.

The Ego hates meaninglessness more than it hates pain. Menelaus would rather cling to a painful lie (the war was necessary) than accept a liberating truth (the war was a mistake). This mirrors the resistance we see in therapy: patients often cling to their trauma narratives because letting go would mean admitting they suffered “for nothing.”

The Dissolution of the Phantom

The turning point comes when a messenger arrives to tell Menelaus that the Helen in the cave has vanished into the sky. The illusion dissolves itself.

This is a metaphor for Disenchantment. In every relationship (or career, or ideology), there comes a moment where the projection fails. The “Perfect Partner” is revealed to be human; the “Dream Job” is just work. This moment is painful, but it is the prerequisite for reality. As Jung said, “There is no birth of consciousness without pain.”

Part V: The Alchemical Wedding (Coniunctio)

Once the Phantom is gone, Menelaus and Helen can finally meet. This reunion represents the Coniunctio—the alchemical wedding of opposites.

Integrating the Shadow

Helen is not the innocent victim she claims to be, nor is Menelaus the glorious hero. They are both damaged, aging survivors.

* **Helen** brings the wisdom of the **Unconscious** (Egypt). She has learned magic, trickery, and prophecy from the priestess Theonoë.

* **Menelaus** brings the scars of the **Conscious World** (War).

Their escape plan requires them to work together. Helen uses her “Trickster” energy (deceiving the Egyptian King) while Menelaus uses his “Warrior” energy. This symbolizes the integration of the **Animus** (Action) and **Anima** (Insight) necessary for Individuation.

Part VI: Clinical Applications for Modern Therapy

How does a 2,500-year-old play help us today? It provides a framework for understanding Relational Trauma and Limerence.

1. Limerence vs. Love

Many clients suffer from “Limerence”—an obsessive, romantic infatuation. Limerence is love for a Phantom. The limerent person is in love with their own projection, not the other person. The cure, as in the play, is the “Cave Scene”—bringing the Phantom into the light and letting it dissolve so that real connection can happen.

2. The “Phantom” of Social Media

In the digital age, we all have an Eidolon—our curated online persona. We project happiness and success (The Cloud Helen) while our real selves sit in exile (Egypt), often feeling lonely or inadequate. Therapy helps bridge the gap between the digital Phantom and the analog Self.

3. Divorce and the “War for Nothing”

In high-conflict divorces, couples often fight a “Trojan War” over assets or custody. Often, they are not fighting the person in front of them; they are fighting a Phantom of “The Betrayer.” Recognizing that the war is being fought over an illusion can sometimes de-escalate the conflict.

Part VII: Conclusion – The Restoration of Reality

Euripides’ Helen ends happily, but it is a sober happiness. The gods do not fix everything; the couple must save themselves through wit and solidarity. The play teaches us that the “Heroic” phase of life (fighting wars for projections) must end. It must be replaced by the “Human” phase—accepting the complexity of the other person.

We are left with a profound challenge: Can we bear to let our Phantoms dissolve? Can we forgive the world for not matching our projections? If we can, we might find that the reality waiting for us in Egypt is far richer than the cloud we chased in Troy.

Further Reading: The Archetypes of Greek Drama

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

The Trojan War Cycle

- The Oresteia: The curse of the House of Atreus and the birth of justice.

- Ajax: The collapse of the rigid warrior ego.

- Philoctetes: The archetype of the Wounded Healer.

- Iphigenia in Tauris: Exile, trauma, and the redemption of the sibling bond.

The Feminine & The Shadow

- Medea: The rage of the betrayed Anima and the destructive mother.

- The Bacchae: The consequences of repressing the irrational (Dionysus).

- Hippolytus: The fatal conflict between instinct and purity.

- The Women of Trachis: Jealousy and the destruction of the Hero.

Bibliography

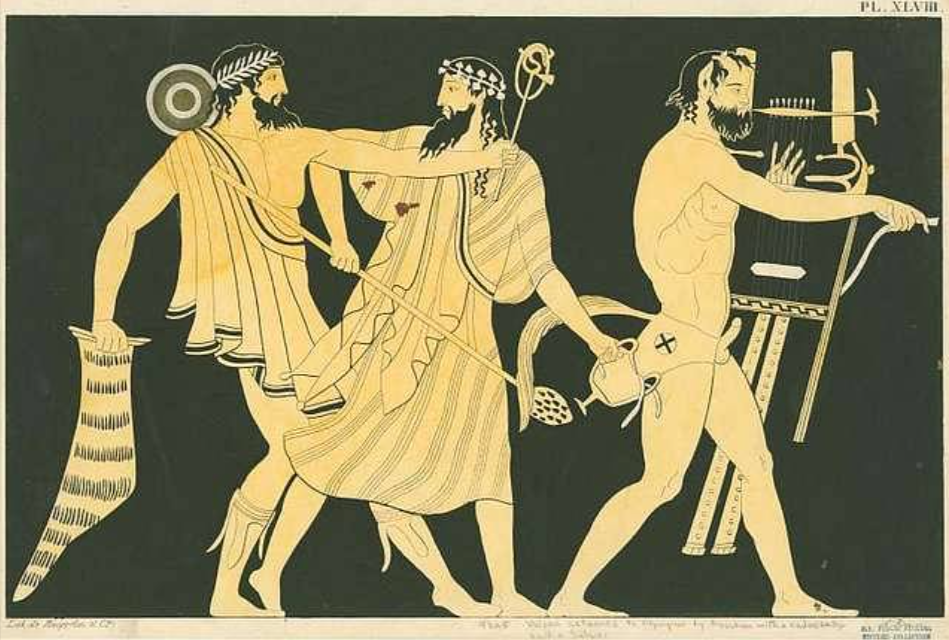

- Euripides. Helen. Translated by Richmond Lattimore. University of Chicago Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press.

- Burnett, A. P. (1971). Catastrophe Survived: Euripides’ Plays of Mixed Reversal. Oxford University Press.

- Whitman, C. H. (1974). Euripides and the Full Circle of Myth. Harvard University Press.

- Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Shambhala.

0 Comments